| [1] | Jeyapalan Kasipillai, A comprehensive guide to Malaysian taxation under self assessment system, 2nd ed., Selangor: McGraw Hill, 2005. |

| [2] | Cendric Sandford, “Self assessment for income tax: Another view”, British Tax Review, vol.3, pp.674-680, 1994. |

| [3] | Binh Tran-Nam, Chris Evans, Michael Walpole, Katherine Ritchie, “Tax compliance costs: Research methodology and empirical evidence from Australia”, National Tax Journal, vol.53, no.2, pp.229-252, 2000. |

| [4] | Bahro A. Berhan, & Glenn P. Jenkins, “The high costs of controlling GST and VAT evasion”, Canadian Tax Journal, vol.53, no.3, pp.720-736, 2005. |

| [5] | Economic Report 2011/12, Treasury of Malaysia 2011, Ministry of Finance: Kuala Lumpur, retrieved from http://www.treasury.gov.my. |

| [6] | Economic Report (various years), Treasury of Malaysia, Ministry of Finance: Kuala Lumpur, retrieved from http://www.treasury.gov.my. |

| [7] | Richard A. Musgrave, “Short of euphoria”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol.1, no.1, pp.59–72, 1987. |

| [8] | Inland Revenue Board (IRB) Website. Online available: http://www.hasil.gov.my |

| [9] | Jeyapalan Kasipillai, A guide to advanced Malaysian taxation, Selangor: McGraw Hill, 2010a. |

| [10] | Inland Revenue Board (IRB) Publication, 2008. Online available: http://www.hasil.gov.my |

| [11] | V. E. L. Wee, “An analysis of tax reform in Malaysia” Doctoral dissertation, retrieved from Electronic Theses Online Service: British Library, 1997. |

| [12] | The Star Online, “Private consumption and investment key drivers”, 2007, September 8. Online available: http://biz.thestar.com.my/news/ |

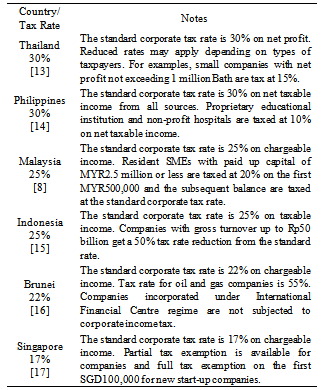

| [13] | Revenue Department of Thailand. Online available: http://www.rd.go.th |

| [14] | Bureau of Internal Revenue of Philippines. Online available: http://www.bir.gov.ph |

| [15] | Directorate General of Taxes of Republic Indonesia. Online available: http://www.rd.go.th |

| [16] | The government of Brunei Darussalam official website. Online available: http://www.rd.go.th |

| [17] | Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore. Online available: http://www.rd.go.th |

| [18] | Income Tax Act, 1967. Online available: http://www.hasil.gov.my |

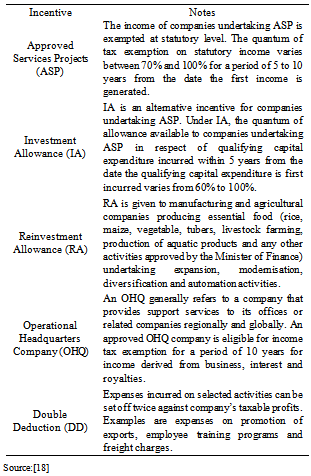

| [19] | A. M. Sassi, “Tax incentives and inter-state fiscal competition: The search for a regulatory framework” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Manchester, United Kingdom 2002. |

| [20] | David J. Arnold, John A. Quelch, “New strategies in the emerging markets”, Sloan Management Review, vol.40, no.1, pp.7-20, 1998. |

| [21] | Hiromitsu Ishi, The Japanese tax system, 3rd Ed Oxford: Oxford Press, 2001. |

| [22] | Ern C. Loo, “Tax knowledge, tax structure and compliance: A report on a quasi-experiment”, New Zealand Journal of Taxation Law and Policy, vol.12, no.2, pp.117-40, 2006. |

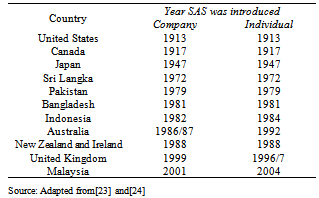

| [23] | Mohd R Palil, “Tax knowledge and tax compliance determinants in self assessment system in Malaysia”, Doctoral dissertation, Retrieved from Electronic Theses Online Service: British Library, 2010. |

| [24] | Ern C. Loo, Juan K. Ho, “Competency of Malaysian salaried individuals in relation to tax compliance under self assessment”, eJournal of Tax Research, vol.3, no.1, pp.47-64, 2005. |

| [25] | Inland Revenue Board (IRB) Annual Report (2001). Available online: http://www.hasil.gov.my |

| [26] | Jeyapalan Kasipillai, Rising costs of tax compliance, The Star Online, 2007, September 1. Available online: http://biz.thestar.com.my/news/story.asp |

| [27] | Rex Marshall, Malcom Smith, Robert W. Armstrong, “Self-assessment and the tax audit lottery: The Australian experience”. Managerial Auditing Journal, vol.12, no.1, pp.9-15, 1997. |

| [28] | Jeyapalan Kasipillai, Mustafa M. Hanefah, “Tax professionals’ views on self assessment system”, Analisis 7, no.1&2, pp.107-122, 2000. |

| [29] | Veerinderjeet Singh, Malaysian Tax Administration, 6th ed., Kuala Lumpur: Longman, 2003. |

| [30] | Inland Revenue Board (IRB) Annual Report, 2006. Available online: http://www.hasil.gov.my |

| [31] | James Andreoni, Brian Erard, Jonathan Feinstein, “Tax compliance”, Journal of Economic Literature, vol.36, no.2, pp. 818-860, 1998. |

| [32] | Mohamed Ariff, Jeff Pope, Taxation and compliance cost in Asia Pacific economies, Sintok: University Utara Malaysia Press, 2002. |

| [33] | Kevin R. Fall, W. Richard Stevens, TCP/IP Illustrated, Volume 1: The Protocols, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley, USA, 2011. |

| [34] | Mayank Suhirid, Kiran B Ladhane, Mahendra Singh, Vishwas A Sawant, "Lateral Load Capacity of Rock Socketed Piers Using Finite Difference Approach", Scientific & Academic Publishing, Journal of Civil Engineering Research, vol.1, no.1, pp.1-8, 2011. |

| [35] | Mohemed Almorsy, John Grundy and Amani S. Ibrahim, "Collaboration-Based Cloud Computing Security Management Framework", in Proceedings of 2011 IEEE 4th International Conference on Cloud Computing, pp. 364-371, 2011. |

| [36] | Online Available: http://journal.org/ajb. |

| [37] | A. Karnik, "Performance of TCP congestion control with rate feedback: TCP/ABR and rate adaptive TCP/IP", M. Eng. thesis, Indian Institute of Science, India, 1999. |

| [38] | J. Padhye, V. Firoiu, D. Towsley, "A stochastic model of TCP Reno congestion avoidance and control", Univ. of Massachusetts, Tech. Rep. 99-02, 1999. |

| [39] | Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specification, IEEE Std. 802.11, 1997. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML