-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2012; 2(6): 115-121

doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20120206.04

Why is It that I am not Warren Buffett?

Elena Chirkova

Economics Department, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Pokrovski Boulevard 11, Moscow, 109028, Russia

Correspondence to: Elena Chirkova , Economics Department, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Pokrovski Boulevard 11, Moscow, 109028, Russia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This article offers a new explanation of the Warren Buffett’s investment phenomenon. This explanation is different from that offered by the promoters of the value investing who suggest the idea of the existence of a superior investment strategy and from that put forward by the advocates of the efficient market theory who discuss the role of pure luck. In the author’s opinion, Warren Buffett’s investment success is best explained by a purposefully built sustainable competitive advantage over other investors in a particular market niche. This part of the success story is costly to replicate and most likely the establishment of such an advantage would take many years. The specific investment strategy and luck play a partial role.

Keywords: Warren Buffett, Value Investing, Efficient Market Theory, Competitive Advantage, Institutional Behavior

Article Outline

1. Introduction: The Puzzle of Warren Buffett

- Warren Buffett is the most successful investor of our time. He started investing in the stock market in the 1950-s. His initial capital consisted of savings that he put aside while working as a newspaper delivery boy. According to Forbes estimate in 2008 his net worth amounted to $62 billion and he enjoyed the No. 1 ranking in the Forbes list of the wealthiest people of the planet. Buffett’s annualised return on investment has reached 20% in nominal terms for the period of more than 50 years. From 1976 to 2006 Berkshire Hathaways’1 stock portfolio beat the S&P 500 Index by 14.65 percentage points, the value-weighted index of all stocks by 10.91 percentage points, and the Fama and French characteristic portfolio by 8.56 percentage point a year[17].Financial scientists have been dismissing the Warren Buffet phenomenon for a long time. According to Buffett’s biographer Roger Lowenstein, a leading American finance scholar and the Nobel price winner William Sharp called Buffett a “3-sigma event”, a statistical aberration so out of line as to require no further attention»[14, p. 312]. Sharp made his comment before 1995 when the Lowenstein’s book was published. Since then Buffett has only increased the gap between him and all other investors, and analysts have transformed the “3-sigma event” into a 5-sigma and even a 6-sigma event.The studies that have appeared since 2005 show that Buffett’s investment results cannot be explained just by luck. For instance, this is one of the conclusions of the most recent study of Buffett’s performance[14]. The authors place Buffett’s performance of beating the market in 28 out of 31 years in the 99.99 percentile, however once the authors incorporate the magnitude of Berkshire’s outperformance, they find that the “luck” explanation is unlikely even if they take into account the ex-post selection bias. The authors also find that Berkshire’s performance cannot be explained by assuming that Berkshire’s investment strategy is high risk. They also find that Berkshire’s triumvirate of Warren Buffett, Charles Munger and Lou Simpson posses investment skill. In short, simple luck will not explain Buffet's success. We will show that knowing the 'right' theory is also insufficient to achieve results as extraordinary as those of Warren Buffett. However, other scientific explanations of his results are yet to be provided, and this is what the author will attempt to do in this article.

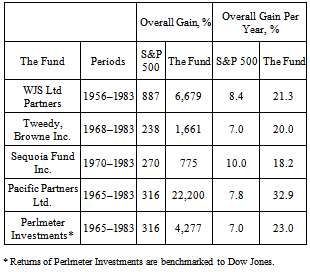

2. Is the “Wright” Theory Able to Explain Buffett’s Performance

- In the article “Superinvestors of Graham and Doodswill” that he published in 1984[5] Buffett responded to the claims of some scholars and journalists that his success could be an anomaly — “random games produce big winners” — inherent in the probability games. Buffett uses the following example. “Let's assume we get 225 million Americans up tomorrow morning and we ask them all to wager a dollar. They go out in the morning at sunrise, and they all call the flip of a coin. If they call correctly, they win a dollar from those who called wrong. Each day the losers drop out, and on the subsequent day the stakes build as all previous winnings are put on the line. After ten flips on ten mornings, there will be approximately 220,000 people in the United States who have correctly called ten flips in a row. They each will have won a little over $1,000. <…>Assuming that the winners are getting the appropriate rewards from the losers, in another ten days we will have 215 people who have successfully called their coin flips 20 times in a row and who, by this exercise, each have turned one dollar into a little over $1 million. $225 million would have been lost, $225 million would have been won. By then, this group will really lose their heads. They will probably write books on “How I turned a Dollar into a Million in Twenty Days Working Thirty Seconds a Morning ”. Worse yet, they'll probably start jetting around the country attending seminars on efficient coin-flipping and tackling skeptical professors with, "If it can't be done, why are there 215 of us? ” By then some business school professor will probably be rude enough to bring up the fact that if 225 million orangutans had engaged in a similar exercise, the results would be much the same…”. Buffett is clearly familiar with the arguments of the efficient market hypothesis.Buffett continues: “I would argue, however, that there are some important differences in the examples I am going to present. For one thing, if (a) you had taken 225 million orangutans distributed roughly as the U.S. population is; if (b) 215 winners were left after 20 days; and if (c) you found that 40 came from a particular zoo in Omaha, you would be pretty sure you were on to something. So you would probably go out and ask the zookeeper about what he's feeding them, whether they had special exercises, what books they read, and who knows what else. That is, if you found any really extraordinary concentrations of success, you might want to see if you could identify concentrations of unusual characteristics that might be causal factors”. In Buffett’s opinion, “a disproportionate number of successful coin-flippers in the investment world came from a very small intellectual village that could be called Graham-and-Doddsville. A concentration of winners that simply cannot be explained by chance can be traced to this particular intellectual village. <…> In this group of successful investors… there has been a common intellectual patriarch, Ben Graham. <…> They have gone to different places and bought and sold different stocks and companies, yet they have had a combined record that simply cannot be explained by the fact that they are all calling flips identically because a leader is signaling the calls for them to make. The patriarch has merely set forth the intellectual theory for making coin-calling decisions, but each student has decided on his own manner of applying the theory”. I would also add that the patriarch died in 1976. Let us consider the idea of the “common intellectual patriarch”. Buffett names four fund managers who worked in the Graham’s company and three other pupils of Graham. The results of the funds managed by five of those seven managers are presented in table 1. In addition to these five managers, Buffett includes in the same “village” his partner at Berkshire Charlie Munger, a lawyer by education who, according to Buffett, was influenced by Graham. In the same “village” we will also find two pension funds in whose management Buffett was involved (those are funds of the Washington Post and The FMC Corporation), and, obviously, his own results achieved while managing Buffett Partnership2. All these results are very impressive.3

|

3. Warren Buffett’s Key Success Factors

3.1. The Personal Situation: Character, Initial Capital, etc

- Buffett was born to a wealthy and educated family. His father was a congressman. Although Warren eventually refused to accept his share of family inheritance in favor of his sister, probably to guarantee the robustness of his experiment, the financial status of his family contributed to his success in an indirect way. As a child Buffett had a part-time job and even established his own small businesses. He sold Coca-Cola, resold used golf balls, worked as a newspaper delivery boy and installed music playing machines at the hairdresser shops. The financial prosperity of his family allowed him to save 100% of his income and to build up a sizable capital when he was still very young. Buffett earned his first 10000 dollars (apx. 90000 in today’s money) by the age of 20, before his first serious investment in the stock market. Buffett was never interested in material consumption. He said that there was nothing material in the world that he would want very much. Owing to a low level of personal spending, his savings have remained very high during his entire life and he has invested nearly all his earnings. It is well known that the success of Berkshire is a joint achievement of Buffett and his intellectual partner Charlie Munger. Since the start of their partnership in the middle of the 1960-s the partners gained financial weight proportionately, but by the 1990-s Buffett’s fortune was 42 billion, while Munger’s was three, as Munger’s living expenses were much higher than those of Buffett and the initial capital that he had invested in Berkshire – lower.5 The gap in the level of wealth between Buffett and Munger has been determined by their respective lifestyle preferences. If Buffett were more interested in personal spending, his investment achievements may not have been as extraordinary and he might have become known as a more “ordinary” billionaire.

3.2. Favorable External Circumstances and Luck

- Let us consider the role of luck in Buffet’s success. Buffett possessed a sizable capital at the start of his investment career6. This fact can be partially explained by luck of his ancestry. He also caught a lucky chance quite a few times in his investment career. Firstly, he established his business in a very favorable year. The shares had been already going up for some time after the stagnation of the 1930–1940-s caused by the Great Depression, but the first large scale market contraction was far away in 1973. So the start of Buffett’s career coincides with a long bull market. Secondly, there is a certain luck in Buffett’s relationship with Benjamin Graham. Graham taught Buffett the wisdom of the profession. Graham also recognised Buffett as the brightest student of his theory7 and, when retiring, he left all his clients to Buffett. Buffett inherited Graham’s clientele at the age of 27. Buffett would probably have developed his own client base without Graham’s help, but it would have taken him much longer and would have affected his early income and savings. Another important event was the acquaintance with Charlie Munger in 1959. Munger is six years older than Buffett and at a time of their meeting he probably had a broader investment experience than Buffett. Having a “senior partner”, as Buffett calls Munger, allowed Buffett to learn from the experience and mistakes of others. For instance, Munger had an unsuccessful exposure to technology stocks in the 1950-s. He avoided losses, owing to a rapid change of technology, only by miracle. This experience prepared Buffett and Munger to “miss” the internet boom, as they put it, 30 years later. Let us look at the purchase of the major furniture retailer, Furniture Mart, in Omaha Nebraska in 1983. An excellent company with a significant future growth potential was acquired for approximately six times annual earnings which was a very low price for such an asset. We have to do justice to the genius of Warren Buffett. He had been following this business for a long time and chose a very good moment to make an offer. He used the friction between the elderly owner of the business, Mrs. Rose Blumkin, and her sons, who were also involved in the management of the company. Buffett promised Rosa that after the sale she would manage the shop as usual and he would not intervene. Upon her agreement to sell the business, he closed the deal in a matter of minutes. He skipped due diligence and returned to her office with a check, not giving her time to reconsider the terms. Later Rosa asserted that the shop which was bought for 60 million was worth at least 100 million. It is Buffett’s achievement that he succeeded in making such an attractive deal, however not every investor meets a 95-year old woman prepared to sell her business for half the price in order to avoid being controlled by her sons. And this is not the only example in Buffett’s investment career.

3.3. Outstanding Abilities

- Buffett was highly committed since a very early age. He became interested in the stock market at the age of 6 or 7 and in 2000 he jokingly commented that he always regretted that he had not started earlier. At the age of eight the young genius was reading investment books from the library of his father. Two years later he borrowed all investment texts that he could find from the local library. Eventually Warren’s enthusiasm about investing became even stronger. And now at the age of 78 it is not any lower. We need to take into account Buffett’s outstanding abilities also. He is talented both in sciences and humanities. Buffett is good at math, is a Pulitzer price winner, a good bridge player and a fantastic psychologist. His abilities in math and interpersonal skills helped him achieve his success in investing. The math is needed to value the acquisition targets and the interpersonal skills help negotiate with the owners. One of Buffett’s famous phrases is “some guys chase girls, I chase companies”[10, p. 1367]. Buffett also has considerable work capacity. When he was young, he studied 2000 company annual reports a year, and now he reads “only” half of that. Besides, Buffett has phenomenal memory.

3.4. The Legal Structuring of the Business

- Warren Buffett chose not to structure his business as a classic fund managed by a management company. And this is one of the key factors of his success. The two-level structure of a fund with a management company used at the time of the Buffett Partnership was liquidated in 1966. In 1969 Buffett took control over a small public company Berkshire Hathaway and that company became his investment holding vehicle for all his acquisitions and portfolio investments. It turned out that a controlled public company has a number of significant advantages over a mutual fund as an investment vehicle. The unit-holders of a publicly held mutual fund can seriously influence the result of the fund manager by taking money out of the fund when stock prices are falling and investing into the fund when the market is at its peak level. A fund is forced to sell assets in order to raise liquidity in the periods of low prices and to buy shares to invest new capital at the market highs. A prominent money manager Peter Lynch commented about this: “…at the very moment I would prefer to be a buyer I had to be a seller. In this sense shareholders play a major role in the fund’s success or failure”[16, р. 133]. The shareholders ofBerkshire Hathaway cannot influence Berkshire’s performance. If Berkshire shares fall Buffett does not need to sell any assets of the company, if they increase in price he does not need to buy. It is crucial for Buffett’s track record that he accumulated the capital sufficient for acquiring a public company and managed to get control over Berkshire, albeit a small and dying company at the time, when he was 39, a relatively young age. Since that time, for the last 40 years, he has been investing through the “right” legal structure. Unfortunately Buffett never commented on whether the change of the investment vehicle was a thought-out strategy or a fortunate coincidence.

3.5. Access to Information

- Buffett’s connections in business and politics are extensive. Originally not a highly connected investor, Buffett owes a considerable deal of his success to his acquaintance with Kathrin Graham, the owner of The Washington Post, where Buffett is a shareholder. Buffet started investing in Mrs. Graham’s family business in 1977. Initally she was suspicious of Buffett’s acquiring parts of her company, despite that he was accumulating only the non-voting shares, but eventually Buffett and Graham met and became close friends. Katherine, who was an acquaintance of Jackie Kennedy, Richard Nickson, Lindon Jonson, Margareth Thatcher, Henry Kissinger, Indira Handi, the Price of Whales, Ronald Reagan, George Bush Senior, Bill Clinton and others, introduced Buffett to her social circle. While making investment decisions Buffett has had a rare chance to supplement his own analysis by information received through his circle of contacts, which also includes the resourceful shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway. Mary Buffett, a former daughter-in-law of Warren, in her book[1], co-authored with David Clark, advises to analyse investments thoroughly, “as does Warren”, and to conduct “field studies”. She encourages investors in a particular stock to visit a shop where the goods produced by the company are sold and discuss with the shop assistant how those products are perceived by consumers and how they sell. This advice certainly makes sense, but through his social circle, Buffett has other and more serious sources of information. Buffett’s circle of contacts is not only a source of valuable information. It is also a powerful intellectual resource. The discussions with Buffet’s closest friend, Bill Gates, must be inspiring and stimulating.

3.6. Buffett’s Sustainable Competitive Advantage as an Investor and Uniqueness of his Market Niche

- Buffett as a “collector” of companies with sustainable competitive advantage has transformed his own acquisition business into a business with a similar competitive advantage. As a result many entrepreneurs who think about selling their businesses are prepared to deal with Buffett exclusively and are ready to accept a lower price, which makes Buffett’s competitive advantage quantifiable. My educated guess is that this discount is around 20% from the maximum possible market price. Buffett has created a unique niche of the white night and a friendly buyer. Upon acquiring a business Buffett does not dismiss its former owner if the latter is prepared to manage the company further – «… nothing ever happens to our managers. We offer them immortality», – says Buffett[10, p. 1353]. As Buffett buys only quality companies and, if a company is good enough to be acquired by Buffett, it already has excellent management. To make a former owner comfortable in a new capacity of a manager accountable to someone else Buffett adheres to the laisser-faire policy toward the management of Berkshire subsidiaries. Buffett helps his managers only if his help is wanted but he does not interfere in the decision-making process, if his involvement is not solicited. One of Berkshire’s CEOs remarked that Buffett “creates the image of ownership without having it”[18, p. 278], and many are prepared to pay for this illusion in a form of lower selling price of the business. Buffett buys businesses “forever”, as he puts it, and he is neither a strategic buyer, nor a financial investor. Buffett is not a strategic buyer because he does not restructure businesses that he buys, does not look for synergies with his existing similar businesses and does not merge new businesses with other companies in Berkshire’s portfolio. But he is not a financial investor either as he does not resell the businesses after a few years. Buffett removes the threat of any restructuring even in the remote future. This attracts to his circle those business owners who are uncomfortable with selling “pearls” created by their own hands to competitors against which they struggled for many years. These entrepreneurs are reluctant to sell their companies to investment funds also because these funds have a relatively short term investment horizons of 3 to 5 years. Some sellers are concerned about selling a business in a leveraged transaction as such a sale increases the risk of the company’s bankruptcy in the future. Buffett never finances his acquisitions with debt and is always ready to offer 100% cash. Buffett sends a very clear signal that he is a friendly buyer. For example, he does not conduct due diligence. An owner of a furniture retail business acquired by Buffett commented on the transaction: “It is a new concept in business. It is called trust”[18, p. 278]. Buffett deals only with decent people and preferably those who want to sell their businesses to Buffett and not just to an any buyer. Such sellers have no intention to maximise the price by any means. Buffett commented on this: “We find it meaningful when an owner cares about whom he sells to. We like to do business with someone who loves his company, not just the money that a sale will bring him (though we certainly understand why he likes that as well). When this emotional attachment exists, it signals that important qualities will likely be found within the business: honest accounting, pride of product, respect for customers, and a loyal group of associates having a strong sense of direction. The reverse is apt to be true, also. When an owner auctions off his business, exhibiting a total lack of interest in what follows, you will frequently find that it has been dressed up for sale, particularly when the seller is a “financial owner”. And if owners behave with little regard for their business and its people, their conduct will often contaminate attitudes and practices throughout the company” [4]. “If you have to go through much investigation something is wrong”[18, p. 192], and Buffett does not invest in such companies in principle. There are no documented cases when after purchase problems were found. Buffett is a great motivator. To be part of Berkshire’s family is not only prestigious but also imposes a lot of responsibility. Berkshire’s CEOs think about how not to “disappoint Warren”[18, p. 192]. The financial motivation of Berkshire’s CEOs is linked exclusively to the return on capital but not to the growth of the business. Option schemes are not used because of the motivation distortion: an option holder does not bear a downside risk and receives either nothing or an upside, while a shareholder has the downside risk also. It is prestigious to sell business to Warren Buffett. Such a deal means that one is allowed into a private club where only selected few get membership. One such owner of a chain of jewelry shops, Barnett Helzberg, even published a book called “What I Learned before I Sold to Warren Buffett”[9]. Prestige associated with selling to Buffett also contributes to Buffett’s attractiveness as a buyer. If Buffett’s strategy is so successful, why is not it replicated? Here is Buffett’s answer: “the corporate culture he has established started because he took over a small enterprise at a young age (34) and, because he did not have to retire at 65, he had enough time to establish momentum. Most CEOs inherit a culture with a short time frame in which to put their thumbprints on their organizations. In addition, these businesses are usually so large that they become resistant to change, even if the CEOs have better management methods[18, p. xii].In addition Buffett’s competitive advantage isstrengthened by a competent use of game theory in merger and acquisition deals, where, for instance, the seller names the price first and an offer is considered by Buffett only once. There is a possibility to make a deal very quickly with a buyer with the large financial cushion (“if you want to shoot rare, fast-moving elephants, you should always carry a loaded gun”)[2]. The non-bureaucratic decision making process and skipping of due diligence in Berkshire are also important.Buffett is an investor dissimilar to any other. Buffett managed to transform his early success partly achieved through fortunate circumstances into a long-termsustainable competitive advantage over other investors. This transformation was a purposeful act for which he deserves full credit. Buffett established his competitive advantage as an investor by the 1980-s when his name became well-known. Since then the number of investment funds in the USA has grown strongly and competition for good businesses intensified, but Buffett was ready for that competition as he had already created a unique market niche for himself.

3.7. The Comparability of Buffett’s Performance with Performance Of other Investors

- Another important tool used by Buffett is the unusual usage of leverage that cannot be replicated by investment funds. Buffett is very cautious about the use of debt in principle, in financing mergers and acquisitions and in investing in the stock market. He has warned investors about the excessive use of leverage many times. However Buffett utilises debt extensively and the return which he generates is the result of the leveraged investing, though Berkshire’s leverage is somewhat specific. The company rarely borrows from banks or issues bonds. A lion’s share of Buffett’s business is insurance and within the insurance sector he focuses on the insurance againstmega-catastrophes, the so-called “supercat” insurance. Insurance premiums are the source of the long-term financing as the time between premiums collections or the raising of debt, and the payouts, the repayment of debt, may reach many years. Such “loans” are raised on extremely attractive financial terms and interest rates can theoretically be negative[3]. Buffett published data on the cost of capital of his insurance business during 31 years (1967–1997). His cost of capital was negative during 17 of those 31 years and during 9 years it was lower than the return on the state bonds[3].8 Buffett uses only very low cost debt, therefore the return on Berkshire shares, strictly speaking, cannot be compared with the returns of mutual funds which do not use debt or raise debt at standard market rates.

4. Conclusions

- The attempted explanation of Buffet’s success fits the framework set out by Nassim Taleb in his books “Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in the Markets and Life” and “Black Swan”[20, 21]. Rare events which, according to modern financial theory, happen with negligible probability in reality take place quite frequently. Taleb calls those events Black Swans. Black Swan is a term used in the science of formal logic. Taleb mostly discusses negative black swans. Buffett is a positive one. He is a positive black swan whose existence, like that of the extreme negative ones, cannot be forecast through modern science. Life will always be richer than the models people design to describe it.Let us draw an analogy with the earthquakes. Geophysicists cannot predict earthquakes with accuracy, however they know that the more disruptive the earthquake the less frequently it happens. It is believed that earthquakes can be described by the law of the critical mass. Sometimes, but very rarely, unique circumstances develop in such a way that the equilibrium fails, however it is not possible to forecast scientifically as to when and where this will happen. This is possibly why there is no single coherent theory of financial bubbles that fits all cases. The American behaviorists Meir Statman and Jonathan Scheid comment in[19] that investors as a whole did not see Buffett’s amasing performance in foresight. The behaviorists here even agree with their opponents adhering to the EMH theory who also claim that a conscious and an a priori winning strategy does not exist. It is clear that by analysing the unique circumstances of Buffett’s biography and investment approach one cannot construct a theory that would generate a financial success comparable to Buffett’s. Moreover the game which is played by many becomes less profitable. It is impossible to predict the next Buffett either. Should the “New Buffett” appear, his success will not be achieved by copying of the strategy of the “original” Buffett. The changing financial environment will require new ideas while the basic investment principles may remain the same. This analysis also allows to re-consider the contradictions highlighted by the supporters of the EMH theory. The EMH does not recognise the existence of a winning strategy generating steady abnormal returns in the modern competitive market, full of sophisticated investors. However, Buffett’s success cannot be attributed only to the application of the “right” winning strategy. Firstly, Buffett, as an investor, created a considerable competitive advantage over his competitors. Nobody would dispute the existence of such an advantage in real economy, but its existence among professional investors is usually not recognised. The companies with a competitive advantage usually enjoy higher return on capital than their competitors. The same story evolves in the financial markets. Warren Buffett is a perfect example. Secondly, the advocates of EMH who search for an explanation of Buffett’s story within the financial theory have no choice other than to declare that his case is accidental or stay silent on the subject. Only the broadening of the analysis by including the factors beyond the financial theory allows to achieve a better understanding of the conundrum. It is not necessary to look at the real world only through the terms of the financial theory. Buffett’s abnormal returns can be attributed to three factors, of which two are financial and one is not: The application of the “right” theory, a version of value investing approach, which increases the returns by approximately three percentage points over the market. This is the easiest part of Buffett’s approach to replicate; The competitive advantage of Buffett as an investor over other investors in a particular market niche. This part of the success story is costly to replicate and most likely the establishment of such an advantage would take many years; The uniqueness of Buffett’s circumstances conducive to his success, which is impossible to replicable in principle. These three factors “legitimise” the case of Warren Buffett, as opposed to the explanations preferred by many financial scientists and journalists who believe that “the reason he is so rich is simply that random games produce big winners but pity the business school professor on fifty grand a year who tries to argue with a billionaire”[15]. Yes, we don’t argue with warren Buffett. We believe in what he says and appreciate what he does.

Notes

- 1. Berkshire Hathaway is Buffett’s investment vehicle. 2. Warren Buffett’s investment company that he owned and managed from 1957 to 1966 before he took over Berkshire Hathaway. 3. This sample is not subjective, i.e. does not suffer from ex-post selection bias. Buffett included in the sample all employees and students of Graham who became fund managers, Munger is the only partner of Buffett in Berkshire, and the two above mentioned pension funds are all funds in whose management Buffett was ever involved.4. It is worth noting that on the same horizon Lynch’s return is comparable with that of Buffett.5. Munger supported eight children while Buffett spent on “only” three kids. Munger paid huge medical bills when one of his sons was dying of cancer. Munger is also more inclined towards luxury consumption, e.g. he has built the longest sailing catamaran in the world, etc. 6. The start of his independent career can be dated to 1957 when he established The Buffett Partnership.7. Buffett started to outperform Graham while being an analyst in his investment boutique.8. Buffett explains his results by creating clear incentives for his employees who are motivated to increase the return on capital employed but not the size of the business. The details of this explanation are beyond the scope of this paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML