-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

2012; 2(2): 20-25

doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20120202.04

Import Liberalization and Import Tariff Yield in Ghana: Estimating Tariff Buoyancy and Elasticity

William Gabriel Brafu-Insaidoo , Camara Kwasi Obeng

Department of Economics, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana

Correspondence to: William Gabriel Brafu-Insaidoo , Department of Economics, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The basic objective of the study is to evaluate the import tariff yield in Ghana, and investigate the impact of import liberalization and customs reforms on the yield. Theory suggests that the relationship between import liberalization and tariff revenue is ambiguous. Empirical studies also indicate that there is no clear link between import liberalization and tariff revenue. To achieve the stated objective, the import tariff buoyancy and elasticity for the pre-reform and reform periods as well as the impact of the liberalization on the yield were estimated. The study confirms the hypothesis that tariff reforms improve tariff revenue yield.

Keywords: import liberalization, tariff buoyancy and the elasticity, tariff revenue

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Trade liberalization has formed a very important component of economic reform programmes in Ghana since 1983. In terms of sequencing, Ghana did not go through the normal intermediary stage of translating quantitative restrictions into equivalent tariffs before gradually reducing the tariffs. Most quantitative restrictions, including import licensing, were eliminated at the same time as the country went ahead to reduce the level and range of tariffs (WTO, 2001). The main reason for import trade liberalization under economic reforms was to reduce the wedge between the official and the parallel exchange rates. Also important was the need to provide foreign exchange to ease import suppression with the aim of increasing output, particularly in the export sector. In this regard, the long-term goal was to replace quantitative restrictions with price instruments. More recently, the impact of the liberalization on trade tax revenue has been a subject of debate. There are concerns about existing ambiguity in both theory and empirical evidence on the relationship between trade liberalization and trade tax revenue in the global context. In theory, liberalization in the form of lower tariff rates and the simplification of rates causes direct trade tax revenue loss, on the one hand, but on the other can also amount to an increase in volume of imports, and hence the tax base and revenue. The net effect depends on a host of factors, including the initial trade regime and the extent of increase in demand for imports. Empirical studies confirm this ambiguous relationship suggested in theory (see Tanzi, 1989; Ebrill et al., 1999; Glenday, 2000; Khattry et al., 2002; Agbeyegbe et al., 2004; UNECA, 2004; Suliman, 2005; Greenaway and Milner, 1993).Oduro (2000) asserts that trade liberalization was fiscally incompatible in Ghana during the 1990s even though Jebuni et al. (1994) find it fiscally compatible for the second half of the 1980s. Such studies rely only on descriptive analyses of changes in tax revenues. They do not apply testable models in investigating the exact impact of trade liberalization on trade tax revenues in Ghana. In order to validate Oduro’s assertion, this study used regression analysis applied to testable models to examine the relationship between import liberalization and import tariff yield in Ghana. The basic objective of the study is to evaluate the import tariff yield in Ghana, and answer the question of whether there is any significant difference in import tariff yield between the pre-reform (1965 to 1982) and reform (1983 to 2007) period. The study is meant to determine the efficiency of the trade tax administration system and to find out whether revenue leakage remains a major problem for import tax after trade liberalization.To meet the stated objective, this study estimated the import tariff buoyancy and elasticity for the pre-reform (1965 to 1982) and reform (1983 to 2007) period in Ghana. The study also estimated the link between import liberalization and customs reforms on one hand and tariff revenue performance on the other hand in Ghana. The only identified study that evaluated the revenue productivity of Ghana’s tax system is that of Kusi (1998) which identified a sharp improvement in the revenue productivity during the reform period. Exchange rate reforms including successive currency devaluations, import liberalization and tax reforms including further improvement in the tax administration are mentioned in the study as some of the major factors accounting for the improved tax revenue performance. Kusi’s approach, however, only covers the period from 1970 to 1993, which makes a sample period of 23 years. In contributing to knowledge on revenue productivity of Ghana’s import tax system, this study adds value by estimating the decomposed tariff buoyancies and extends the study period to 42 years, from 1965 to 2007.

2. Methodology

2.1. Method of Analysis

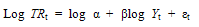

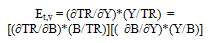

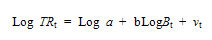

- Two measures are usually used for determining tax yield. These are the buoyancy and the elasticity of a given tax system. The buoyancy measures growth in duty revenue as a result of growth in income, reflecting the combined effects of tax base expansion and discretionary changes in tax rates, base definition, and changes in collection and enforcements of the law. Elasticity measures, on the other hand, control for discretionary tax measures, implying that changes in duty revenues are attributed to automatic or natural growth of the economy (Osoro, 1993). Generally, the buoyancy of a tax is obtained by assuming the following functional form:

| (1) |

| (2) |

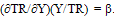

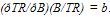

. The buoyancy of a tax system, which generally refers to the responsiveness of tax revenue to a change in income, is defined as:

. The buoyancy of a tax system, which generally refers to the responsiveness of tax revenue to a change in income, is defined as: | (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

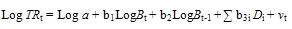

.In determining elasticities, two main techniques are usually used for cleansing the revenue series of discretionary effects. One is that of proportional adjustment, which involves use of historical time series tax data adjusted for discretionary tax measures, as in Mansfield (1972), Osoro (1993), and Muriithi and Moyi (2003). The other is the use of unadjusted historical time series tax data with time trends or dummy variables incorporated as proxies for discretionary tax measures, as in Singer (1968) and Artus (1974).Lack of sufficient data made us opt for the dummy method, usually referred to as the Singer approach. Thus, we introduce dummy variables to control for discretionary tax measures and a lagged base variable into Equation 5 as follows:

.In determining elasticities, two main techniques are usually used for cleansing the revenue series of discretionary effects. One is that of proportional adjustment, which involves use of historical time series tax data adjusted for discretionary tax measures, as in Mansfield (1972), Osoro (1993), and Muriithi and Moyi (2003). The other is the use of unadjusted historical time series tax data with time trends or dummy variables incorporated as proxies for discretionary tax measures, as in Singer (1968) and Artus (1974).Lack of sufficient data made us opt for the dummy method, usually referred to as the Singer approach. Thus, we introduce dummy variables to control for discretionary tax measures and a lagged base variable into Equation 5 as follows: | (6) |

2.2. Data Sources and Definition of Variables

- Annual data for the study was collected from the Ghana Statistical Services, Customs, Excise and Preventive Services, and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. For this paper, the following variable definitions applied. Real import tax or duty revenue was calculated by deflating nominal import duty revenues with the consumer price index. The values of real imports were obtained by deflating nominal imports with import price indices. Real GDP is nominal GDP deflated by GDP deflator.

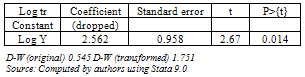

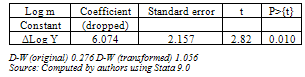

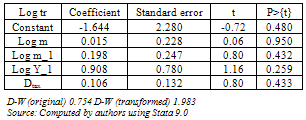

3. Import Tax Yield – Buoyancy and Elasticity

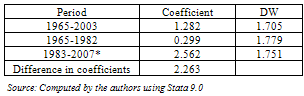

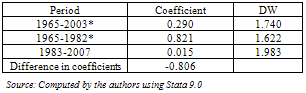

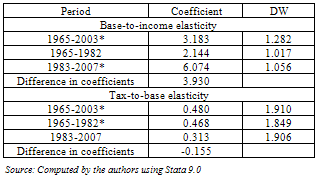

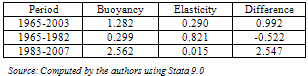

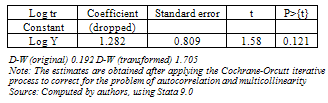

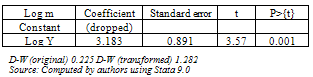

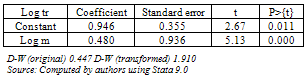

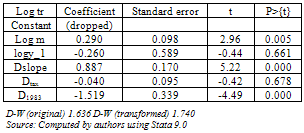

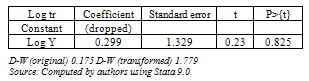

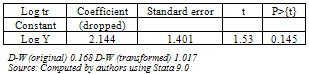

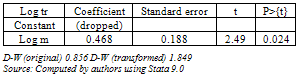

- Estimates of the import tariff buoyancy and elasticity have been derived using the Cochrane–Orcutt iterative procedure, which corrects for the problem of multicollinearity and autocorrelation. Report of the estimates on tariff buoyancy is presented in Table 1. The estimates indicate that import tax has become more buoyant over the period of import liberalization compared to the pre-reform period (before 1983).On the contrary, Table 2 indicates that the import tariff has become less elastic over the period of import liberalization compared with the pre-reform period. The comparatively low elasticity for the reform period might be attributed to the continued prevalence of duty evasion, duty exemptions, corruption in customs administration and smuggling activities.

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions and Policy Implications

- Ghana has been hailed by the international community as one of the countries that have pursued deep economic reforms since 1983. As part of the programme, efforts have been made to reform the external trade sector with import liberalization as an important component. Among the instruments used were reductions in the level of tariffs, simplification of rates into more uniform rates, the removal or relaxation of quantitative restrictions, and the equilibrating role of a liberal exchange rate regime. However, experiences with tax revenues from international trade, particularly during the 1980s and 1990s, raised concerns about whether import trade liberalization conflicts with the revenue generation objectives of economic reform in Ghana. This has been important because fiscal discipline in the earlier part of adjustment was relaxed and government was no longer prudent with its spending. We have attempted in this study to address one of the prevailing issues in the trade liberalization debate.

4.1. Conclusions

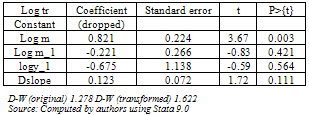

- The basic objective of the study was to evaluate the import tariff yield in Ghana, and answer the question of whether there is any significant difference in import tariff yield between the pre-reform (1965 to 1982) and reform (1983 to 2007) period. To do this we estimated the import tax buoyancy and elasticity in Ghana. The findings from the analysis are as follows:● Import tax has become more buoyant over the period of liberalization compared to the pre-reform period (pre-1983)● Import tariff has become less elastic over the period of import liberalization compared with the pre-reform period. This might be attributed to the continued prevalence of duty evasion, duty exemptions, corruption in customs administration and smuggling activities during the period of reforms (post-1983 period).● The degree of responsiveness of import tax to change in its taxable base declined during the liberalization period compared with the pre-liberalization period. ● Discretionary tax measures, such as reforms made to the tariff structure in conformity to import liberalization, the temporary introduction of special import tax on selected items, and reforms to customs administration such as the granting of operational autonomy, improved tariff revenue mobilization over the liberalization period.● A cursory look at Table A4 under appendix, also indicates that although import liberalization has resulted in some revenue loss, the significance of the interactive slope dummy in explaining tariff revenue suggests that the tariff revenue function has shifted upward as a result of the liberalization. This could mean that the share of commodities subject to tariff in total imports increased. In sum, this study confirms the findings from the earlier work by Kusi (1998) that customs reforms, including tariff liberalization and the overhauling of the tax administration has improved tariff revenue yield and efficiency in Ghana’s import tax system during the liberalization period.

4.2. Policy Implications

- Nevertheless, the study also indicates that there is a continued existence of substantial amount of leakage and inefficiencies in the customs collection system. Thus, customs administration requires further strengthening to generate more duty revenue from imports. Leakages in the customs collection system could in part be attributed to the exploitation of widespread duty exemptions, outright smuggling and import under-invoicing in the country. Public policy should focus on the identification of the major sources of duty revenue leakage. The pervasive use of exemptions creates a gap in the tax base, especially through abuses of the exemptions offered. A further review of the rationale for the duty exemption programme and reduction in range of items exempt from duty payments in Ghana will be required. Improving revenue administration and closing other sources of leakages including import under-invoicing on a committed and continuous basis, will help to broaden the tax base and to recover revenue (IMF, 2005). An effective measure, in this regard, is to strengthen the tax collection system, including institutional reforms (automation and strengthening of monitoring and supervision units). Collaboration with source country Customs officials will help to trace or confirm the actual costs of goods that are often under-invoiced, as is common practice in Ghana. In addition, the promotion of rapid economic growth during liberalization will further shore up tariff revenue for a given level of tariffs (Ebrill, Stotsky and Gropp, 1999).

Appendix

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML