-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2012; 2(1): 15-24

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20120201.03

Privatisation, Labour Conditions and Firm Performance in Uganda

David Lameck Kibikyo

Centre for Basic Research (CBR), Kampala, P. O. Box 9863, Uganda

Correspondence to: David Lameck Kibikyo, Centre for Basic Research (CBR), Kampala, P. O. Box 9863, Uganda.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper investigates the effect of motivation of privatisation by comparing before and after privatisation. Before privatization, both salaries and wages on one hand and fringe benefits on the other were determined by the nature of ownership as well as industry type on the other hand. In purely SOEs, the determination of workers’ conditions was political. Purely SOEs were lavish in granting salary and other benefits to staff explained by state ownership and existing trade unions. FDI, however, tended to ignore the idea of collective agreement and fluffed the trade unions and their restrictive working practices such as working 8 hours a day. Bad conditions in FDI firms always resulted into strikes with varying intensities with casualties to either the crop or management staff. The salary and other benefits also differed among industries, the poorest being recorded in the textile, followed by the plantation-based industries, and utilities last. These SOEs’ lavish conditions of service changed drastically after privatization from permanent and pensionable (PP) to temporary and retrenchable (TT). After privatization, the new buyers cunningly increased salaries for managerial, technical and clerical staff on paper. Practically, however, they recruited most staff to high positions as group employees who did not enjoy negotiated terms. In addition, PSOEs laid off group employees earning shs. 300, 000= and replaced them with those willing to work for shs. 100, 000= per month. The terms casual, temporary, and contract in PSOEs and meant ‘daily but continuous,’ ‘six months to one year,’ and ‘one to three years’ respectively. This was made possible by high unemployment levels in the country. This resulted into falling wage-bill as well as product quality in the tea and sugar sectors. With respect to benefits, after privatization, these depended on industry and profitability unlike before privatization.

Keywords: Privatisation, Labour Conditions, Firm Performance, Uganda

Cite this paper: David Lameck Kibikyo, Privatisation, Labour Conditions and Firm Performance in Uganda, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2012, pp. 15-24. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20120201.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Galal et al (1994) argued that in monopoly situations, the effectiveness of privatization depends on how the public sector is motivated. The implication of this is that it is possible to estimate the effectiveness of such a policy by simply investigating the differences in motivation within state- owned enterprises (SOEs) on one hand, and privatized state-owned enterprises (PSOEs) on the other. If motivation in SOE was same as in PSOEs, privatisation would be expected to have no effect; while if they differed some results would be expected. In this chapter, I measured motivation by pay, fringe benefits, and job security. The chapter has three sections. Part one is on wages and salaries; part two is the fringe benefits, and part three the job security all before and after privatization.Motivation is having the desire and willingness to do something. It can be temporal or dynamic A motivated person can have a short-term goal like learning how to spell aparticular word or reaching for a long-term career goal such as becoming a computer specialist. The subject has been better discussed by Hertzberg’s Motivator Hygiene Theory which explains satisfaction and motivation in the workplace arguing that satisfaction or dissatisfaction are driven by different factors – motivation and hygiene factors respectively. Hertzberg (1968) argues that motivators include challenging work, recognition, responsibility which gives positive satisfaction, while hygiene factors include salary, fringe benefits and job security which do not motivate if present, but if absent would result in de-motivation. The term hygiene factor is used because, like hygiene, the presence would not make you healthier, but absence can cause health deterioration. Empirical evidence supports the motivator-hygiene theory. Steve Bicknell (1959) research into Employee Engagement Data analysis of verbatim comments over 50 companies found a relationship between low hygiene and low Employee Engagement. Employees consistently recorded low scores against management/leadership but happy to complain about leadership since their hygiene factors were bad. This study defines motivation being of the hygiene nature and ignores the motivator type.

2. Wages in the Public (SOEs) and Private Sectors (PSOEs) in Uganda

- Before privatization, SOEs, unlike their FDI counterparts, were lavish in dishing out salaries. Determination of workers’ salaries and wages and other conditions, particularly for the fully SOEs, was based on factors other than production or profitability. On the contrary, the workers’ conditions in enterprises that had some degree of FDIs or where government held minority shares tended to be free of labour restrictions generally. This situation changed after privatization, the new buyers cunningly increased salaries for managerial, technical and clerical staff in agreements. Practically, however, they recruited the staff to high positions as group employees who did not enjoy negotiated terms. In addition, PSOEs laid off more highly paid group employees earning shs. 300, 000= and replaced them with those willing to work for shs. 100, 000= per month. This resulted into falling wage-bill as well as product quality in the tea sector. During this era, wage determination was political but also depended on whether the SOEs were purely government of FDI.Determination of workers’ salaries and wages and other conditions, particularly for the fully SOEs, was based on factors other than production or profitability. For instance, a UCB regulation stated that ‘the salary, wages, fees, or other remuneration or allowances paid by the Bank were in no way to be computed with reference to the net or other profits of the Bank’ [22/1965, s.11 (3)]. This implied that even if losses were made, salaries and benefits would continue rising in case of profits there would be no bonus for the workers, thereby de-linking pay from productivity explained by state ownership and TU influence. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)On the contrary, the workers’ conditions in enterprises that had some degree of FDIs or where government held minority shares tended to be free of labour restrictions generally. The sugar and the tea factories suffice to illustrate the differences in motivation in the purely SOEs and FDI firms. Firms with some element of foreign ownership tended to ignore the idea of collective agreement and fluffed the trade unions and their restrictive working practices. Bad conditions in FDI firms always resulted into strikes with varying intensities. In the big enterprises, the workers used to react through strikes and other violent actions that also differed in industry type. In the Tea and the Sugar plantations, the workers destroyed the crop up to 1996, while in the textiles industry, the workers harassed the management and the strikes were less violent. In 1990, SOEs exceeded the non-SOEs trade union membership; but this was reversed after privatization. Trade union membership was 67, 000 and 34,500 for SOEs and non-SOEs respectively before privatization in 1990. After privatization, the corresponding figures were 75,359 and 92,135 respectively.

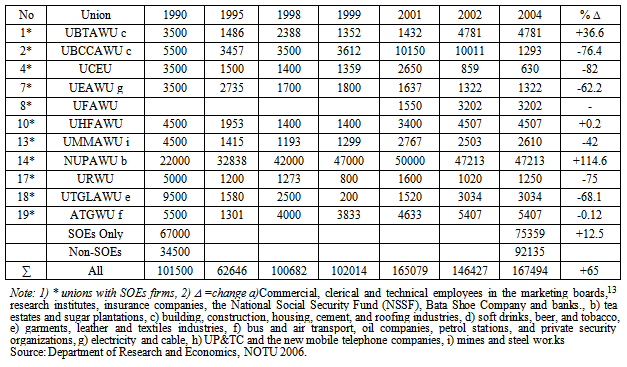

2.1. Unionization in Public Sector in Uganda

- Being a union member meant to have a membership card, being up-to-date with the monthly contributions1 and having an ideology. For instance, a member was baptized and initiated. While the former turned a member into either ‘a brother’ or ‘sister’; the latter, took a worker through training in ideology and work values. Employment was not taken as a favour but a right or an entitlement.2 Before privatization, SOEs trade unions comprised a small majority of total union membership. Specifically, there were 67,000 employees in 1990 accounting for 66 per cent of total union membership and 0.6 per cent of the 1992 national census respectively. Unions covering SOE staff accounted for more than half of all unions in the country. Specifically, there were eight unions catering for SOE staff out of a total of 17 unions in the country. This unionization was possible due to the government employment policy and socialist tendencies. The government encouraged unionization for purposes of satisfying a social obligation of providing employment to people. In addition, the socialist tendencies of Obote regime gave clout to unions. For instance, President Obote used to say that he loved three people - the students, peasants, and workers.3The sources of TU powers originated from SOEs’ authority to hire and fire. SOEs’ power to recruit and lay-off staff automatically gave unions the right to protect workers’ interests. The terms of hiring and firing of an employee in SOEs were determined by Trade Unions. SOEs that were not given powers to hire and fire did not form unions in which case the parent ministry employed staff and also determined their working conditions, as was the case in UFEL.4 SOEs’ power to hire and fire was given by statutory instrument to either the board or management, and this automatically gave unions the right to protect the workers’ interests. The existence of a union, however, did not always grant every worker the right to be unionized. The unionised levels were negotiable between the employer and the union. Hence, the lowest level of unionization depended on employer-employee agreement5,6,7 usually stipulated in the recognition agreements (Barya, 2001:13). Later, and when privatization had set in, in 1993. Legislation allowed more association limiting the area of non-unionised employees in the private sector to only a very small section of personnel and industrial relations officers. Only officers and employees of the rank of personnel, labour, industrial relations officer, chief Judge, Magistrate of the Court of Judicature and personal secretary were excluded8 (Barya, 2001:15).In addition to the legislation, officers or employees could be excluded from membership of a trade union or employees’ association by mutual agreements between an employer and the trade union to which such officers or employees belonged.9 One impact of TU and SOEs ownership was the share of wages in SOEs expenditure.In firms such as those in agro-processing and textiles, wages formed a big percentage in SOEs total expenditure. For instance, textiles had wages accounting for 47.2%, tiles 24.1%, and energy 51.4% of total expenditure before privatization. This implied that restructuring some of these SOEs through retrenchment and automation in textiles and the energy sectors respectively could have paid dividend. Taking the example of energy and banks, automation in such ventures as pre-paid electricity service could have released meter readers, staff in bill distribution, amount of paper used, and those people who connect and reconnect power. In banking, introduction of ATMs easing staff costs after privatization. Government, however, both before and after privatization refused to lay off citing political reasons.Wages were, however, not the only reason for a big-wage bill although it is difficult to know which of the two: wages or overstaffing was more responsible. Before privatization, SOEs were generally overstaffed especially the fully SOEs. A firm was considered overstaffed if the ratio of line to support staff differed from the straight forward rule-of- the-thumb of two-to-one (UDC, 1990: 6-7, 13). UDC and Hima Cement Industries help illustrate the problem. While UDC had both line and support sections, the support staff rose faster than the line staff numbers. By 1990, she had 22 line and 28 support staff giving a ratio of 1: 1.25 that was considered higher compared to the mentioned rule. In the case of the Uganda Cement Industries Limited (UCIL), although she hardly produced cement she employed about 1,400 workers on full-time pay roll in the 1990s (UDC, 1990:6-7, 13). Overstaffing in SOEs was caused by the government’s policy to employ as many people as possible. It was, therefore, not surprising that SOEs contributed greatly to employment, accounting for 20 per cent of total employment in the manufacturing industry in Uganda in 1963 and 1964. Stoutsdijk (1967:37-8) argued that in 1963, the five manufacturing firms of UDC employed total of 3,905 persons that increased to 4,019 in 1964. Comparing UDC with the country’s employment surveys for the same period of 19,220 and 20,838 accounted for 20 per cent of total employment in the manufacturing industry in both years. A further comparison of Uganda’s employment with the rest of the third world for the 1978-1985 period shows that Uganda’s SOE employment was near Africa’s 19.9 per cent, although it superseded Asia’s of 2.9 per cent, and Latin America’s 2.8 per cent. The Uganda’s SOEs doubled the LDC average of 10.2 per cent implying that Uganda was one of those countries that over-recruited in the SOE sector during the period, although Stoutsdijk (1976) refuted this. These lavish conditions took a stranger turn after privatisation. These union powers took on a stranger turn after privatization.

2.2. Wages after Privatization in Uganda

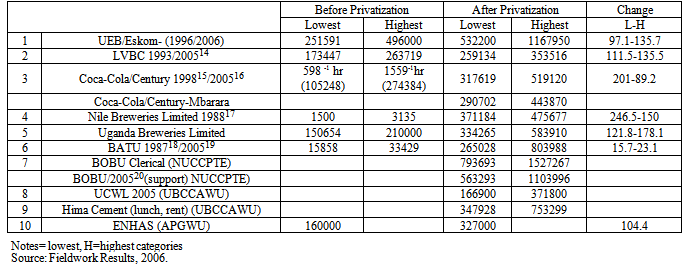

- After privatization, while working conditions improved on paper for the majority of sectors, increasingly few staff enjoyed them. These terms were for permanent staff, yet majority were recruited on temporary and contract terms set by the PSOEs new owners. According to the Table 7.1, salaries increased by 97.1 % to 15.7 times the original figure in the lowest; and 89.2 % to 23.1 times in the highest paid categories respectively after privatization. The rise in salaries was due to growth, union pressure, and competition. Hotels and beverages had some of the highest growth rates and therefore absorbed more workers after privatisation. Hotels and beverages had average growth rates between 1992 and 2006. A second reason for increase in salaries was trade union pressure. As already stated, some trade Unions also still played some role in improving workers’ conditions as the Coca-Cola example shows. The company had some of the worst working conditions in the country whereby payment was fortnightly. The miserable hourly rates ranged between Shs 598 and 1559 and were recorded on clock-cards.10 Union intervention, however, caused monthly payments and better wages and a retirement package that did not exist before.11Third and last conditions improved due to competition both in sugar and telecommunications. In the sugar industry rivalry among KiSW, KSW, and SCOUL ensured that workers conditions improved since they determined product quality. In the telecommunication, conditions improved immediately in UP&TC after privatization, due to competition created by new entrants, MTN and CELTEL. The two companies were involved in poaching skilled workers of UP&TC by paying the workers better salaries than they enjoyed in their previous jobs. However, these terms were declining.12

|

|

3. Fringe Benefits in Public and Private Firms in Uganda

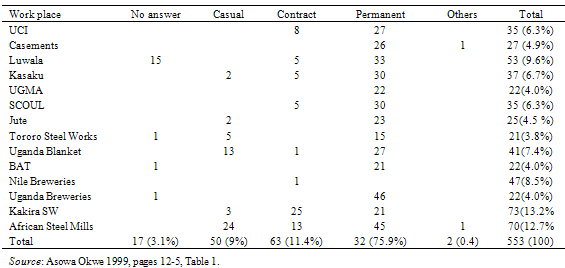

- In this sub-section I represent fringe benefits by allowances and other conditions such as lunch, medical, transport, and hours of work. Before privatization, purely government-owned SOEs were lavish in granting benefits unlike FDI. UP & TC and UCB suffice to illustrate these worker conditions. In the UP & TC, the Minister regularly appointed officers and employees when necessary for the proper and efficient discharge of its functions.16 The Board could also grant pensions, gratuities or retirement allowances to the staff and employees pension, provident fund or super- annuation scheme.17 In addition, it was always possible for officers in the civil service to access SOE posts through secondment18. Hence, SOEs became extensions of the traditional civil service with all the ills of the latter although salaries and benefits were civil service were poorer compared to SOEs. In the UCB, the Managing Director19 appointed most employees on terms and conditions laid down by Board20 as already explained under salaries. Second, most staff on falling sick staff were treated in the company clinics and not a public hospital (Asowa Okwe, 1999:12). Third, the average working day of eight hours was mostly observed, particularly in the fully SOEs firms with 80% of the workers in 14 SOEs (Asowa Okwe, 1999:16-7), this was not the case in FDI. Staff in firms with some element of foreign ownership worked longer hours between 10-12 hours. Hence, in FDIs, working hours and employee numbers changed depending on the volume of work available. For instance, workers laboured for 8.1 hours, 12.2 hours, 13.4 hours, and 8.5 hours in BATU, Kakira Sugar Works (KSW), African Steel Mills (ASM) and Nile Breweries Limited (NBL) respectively. Particularly, in BATU 1984 Limited, the duration of work tended to vary with the volume of work or amount of tobacco available for processing at a particular time (Asowa Okwe, 1999:16-7). In Kakira Sugar Works (KSW) and African Steel Mills the combined total of casual and contract workers were as big as the permanent employees. FDI firms were, however, more geared to productivity than in the entirely government-owned SOEs. In pure SOEs, unlike FDI, government allowed lavish benefits before privatization but this situation changed after privatization whereby wage determination was based on industry-type and profitability.

3.1. Fringe Benefits after Privatization

- After privatisation, fringe benefits such as lunch, transport, and safety standard in PSOEs depended on industry type on one hand, and profitability on the other hand. In early privatization, the government neither prepared for retraining, redeployment of demobilised staff, nor ensured the installation of legal and contractual obligations before reform. Instead, government condoned mistreatment of both the old and new workers in the PSOEs by just signing ‘’no obligation guarantees’’ to the buyers (Barya, 2001:33).The only statutory provisions for the employees in the PSOEs was in the PERDS that simply stated that the Finance Minister would ensure the payment to the demobilized employees arising out of restructuring or liquidations through the establishment of a redundancy account.21 Government through a responsible Minister and the Board of Directors and management of the SOEs could use the sale proceeds in the divestiture account to compensate or provide for demobilized staff arising from divestiture.22

3.1.1. Industry Type and Market Share

- While PSOEs particularly those covered by ATGWU or NUPAWU had taken over tasks that used to be for unions and thereby improving some working conditions with intention of being rated good, industry type and market share was the overriding issue determining work conditions. In the oil companies, all staff including upper management and lower cadres lunched together unlike in the past where senior and junior staff sat separately. In addition, unlike before, all staff were collected in the morning and dropped in the evening using the same transport for both categories of workers. This helped to reduce discrimination. In the plantation industry, issues like protective gear were part of work discipline and ethics and not a safety standard requirement to be enforced by unions such as ATGWU or NUPAWU any more. Issues such as occupational health and safety and training were part of company policy. In the plantations, an officer was employed to take care of such issues, which was not the case before. With respect to safety, all employees had general things like an overall and gum boots but always lacked specific section protective gears such as nose-masks for sprayers or heat-repellent uniform for those working in hot sections like chimneys. The employers defaulted to provide specific gears because they were imported and expensive. Despite the improving conditions, ATGWU still required the members for solidarity and pooling or good practice purposes that meant that despite the general improvement, some oil companies such as GAPCO paid lower rates than others, due to differences in market shares. GAPCO, the Indian-owned firm that bought Esso Uganda Limited, was responsible for failing to sign the new agreement and for four years paid the lowest terms.23 The introduction of ‘Employer of the year Award’ played a major role in continuous review of working conditions particularly in the plantation sub-sector. The gold, silver and bronze medals awards were given to the three employers who treated workers fairly. Employees and trade union officials chose the employers by filling a questionnaire. Employers valued the award because of the publicity it gave to the company and numerous benefits associated with it. Second, competition in the sugar industry among KiSW, KSW, and SCOUL also ensured that workers conditions improved since they determined product quality. Trade Unions also still played some role in improving workers’ conditions as the Coca-Cola example shows. Coca-Cola had some of the worst working conditions in the country whereby payment was fortnightly. The miserable hourly rates ranged between Shs 598 and 1559 and were recorded on clock-cards.24 Union intervention, however, caused monthly payments and better wages and a retirement package that did not exist before.25 Unlike poor conditions in FDIs and unprofitable PSOEs, terms were better in more profitable ones.

3.1.2. Post-1996 Privatization: Profitable SOEs

- On the contrary, privatization of the relatively more profitable Uganda Airlines and utility sector after 1996 brought in more protection of the workers’ rights than before. The new protection, according to Barya, wrongly explained the better terms by the presence of three workers’ MPs who sensitised and lobbied fellow MPs on workers’ interests. Barya wrongly argues that the MPs struggled on their own to bring on board such issues for debate and attention by Parliament. Barya maintains that they articulated and presented workers’ demands directly instead of relying on third parties as used to be the case in the past. Barya does not explain whether the existence of workers’ MPs alone significantly altered the motivation in the post-1996 period when the ideal conditions for motivation indicated otherwise. Hence Barya tends to ignore neo-classical determinants of motivation such as market structure and profitability of enterprises in the utility and airlines sub-sectors. In addition, Barya fails to point out the differences between pre-1996 and the post-1996 firms.26 During sale, it was agreed that small enterprises (loss-making) would be sold first and bigger ones (profit-making) last. Hence, the bigger ones that were sold later, like the UP & TC, UEB and UAC/ENHAS were more profitable than the pre-1996 ones. In the utility sector, on privatization, the UEB and UCC Acts provided that all employees who transferred services to the new bodies27 would do so on similar or better terms as compared to those enjoyed by employees before transfer.28 The new bodies would assume the terms and conditions of service applied to the UP & TC and UEB respectively at the commencement of the two acts.29 The two acts spelled terms of former employees of the UP & TC and UEB who, at the commencement of the statutes 8/1997, were receiving retirement benefits and pensions from the two SOEs would continue to be paid by the government.30 The staffs of both corporations made redundant as a result of the reforms would be paid the calculated and ascertained retirement benefits and pensions from the SOEs before the repealing of UP & TC and UEB.31 A contributory pension fund initially government-financed would be established for the permanent employees of the UP & TC and UEB before any reforms for any staff who transferred to the new bodies.32 In addition, all employees of UP&TC and UEB who transferred to the Uganda Posts Limited (UPL), Uganda Telecom Limited (UTL), the Post Bank Uganda Limited or the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC); and the Uganda Electricity Distribution (UEDCO), Uganda Electricity Generation Company (UEGCO) or the Uganda Electricity Company (UETCO) in case of the power sub-sector would have their terminal benefits calculated, ascertained and transferred to the Contributory Pension Fund (CPF) before commencement of the acts, and any employee who retired, dismissed or terminated for any reasons after transfer would be paid.33 The reality was not as expected fading immediately after privatization in the UP & TC on one hand; while adjusting work conditions in the UEB was slow. Conditions improved immediately in UP&TC after privatization, in the postal and telecommunications due to competition and union pressure created by new entrants, MTN and CELTEL. MTN and CELTEL were involved in poaching skilled workers of UP&TC by paying the workers better salaries than they enjoyed in their previous jobs. However, these terms were declining.34 Current conditions in the MTN and CELTEL were more of window-dressing than handling the problem. Instead of offering favourable terms, the new entrants invested in high-sounding projects but of a temporary nature under the so-called ‘social corporate policy’ such as in education donations, philanthropic activities for society, supporting the aged and HIV/AIDS, orphanages, and cultural institutions.35 In the energy sub-sector, despite the recognition agreements, review of salary and terms and conditions of work were slow. The three firms of UEGCL (ESKOM), UETCL, UEDCL were still upholding the old (UEB) terms and conditions of service36. In the next section, I look at the last measure of hygiene factors-job security.

3.2. Job Security in the Public and Private Sectors

- Just with salary and benefits, SOEs especially the wholly government owned firms, job security was equally guaranteed once employed. The SOEs’ offered lavish terms of permanent and pensionable (PP) but this drastically changed to temporary and re-trenchable (TT) after privatization. Before privatization, particularly in the SOEs that were purely government-owned, the terms and conditions of hiring and firing were permanent and pensionable (PP) (Asowa Okwe, 1999:12). The Board did hiring and firing but the firing of senior staff such as Company Secretary, Chief Accountant and Heads of Department, divisions or projects required approval by the Minister [Decree 24/1974, s.6&7; Decree 23/1974] explained by government policy of job creation as well as TU involvement already explained.Table 7.3 gives some examples of the nature of job security before privatization in both FDIs and fully SOEs. Generally, 75.9% of the employees were recruited on permanent basis (column 5, Table 7.3) against 11.4% contract (column 4, Table 7.3) and 9% casual (column 3, Table 7.3). These SOEs’ lavish conditions of service changed drastically after privatization from permanent and pensionable (PP) to casual workers regardless of rank.

|

|

3.2.1. Job Security after Privatization

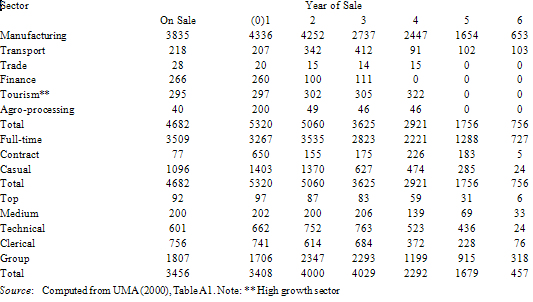

- After privatisation, job tenure became more temporary than before. The casualness is best described by postal union officials. Temporary employment, for instance, in the telecommunication sub-sector, was increasing on temporary, and contract terms for most crucial jobs that required skills. The terms in PSOEs casual, temporary, and contract were characterized and meant ‘daily but continuous,’ ‘six to one year,’ and ‘one to three years’ in the private sector respectively.37 Privatization mostly favoured group employees whose number grew from 52.3 to 69.5 per cent on sale and the sixth year after sale (See Table 7.4, Row 17) already explained. The latter category (earning less than Shs 100, 000 = US$50) replaced her more highly paid counterpart - the upper group employees category (earning Shs 100-300, 000 = US$50- US$150). The upper group employees’ category (earning Shs 100-300, 000=US$50-US$150) were retrenched and replaced by the relatively less paid counterparts (earning Shs 100-300, 000 =US$50-US$150) explained by a need to cut costs but with negative effects on product quality. The impact of job insecurity on product quality is best seen in plantations of tea and sugar. In the tea sub-sector, quality was poor due to the casualness and consequent poor terms of service, among others, that also impacted negatively on tea quality. In comparison, the quality of Kenya tea was better than that of Uganda’s because the former carried out training at Kericho Training Institute.38 Initially, casualization resulted into a drop in the product quality of both the sugar and tea sectors forcing the management, on recommendation of union management and the plantation union (NUPAWU), to change policy. In order to avert the situation, the causal were turned into contract and permanent staff in the sugar industry. The driving force behind layoffs was competition, which required cutting down on production costs through terminations and retirements. At first, employers turned both permanent employees into casual workers who did not enjoy negotiated terms and conditions since they were not unionized. The reason for turning permanent workers into casual ones was to evade paying negotiated terms such as leave, housing, and medical. In the plantation union (NUPAWU), the only fairly permanent employees were the low cadre contract workers including cane cutters, weeders in sugarcane plantations; and sprayers and tea pickers in the tea sub-sector. The contracts were normally for a one-year period but renewable. The high unemployment rate in the countryside made it possible for terms to be changed to a situation whereby formerly permanent workers were recruited as temporary ones.Comparing the three motivation types offer interesting lessons in manual jobs that also required some skills. In the lowest paid tea and sugar cane plantations sector, while wages and fringe benefits fell due to retrenchment of more highly paid and replaced them with relatively lesser paid consequently boosting firm profitability; the bottom line to this labour exploitation was job security. On the contrary, attempts to lower job tenure to lesser permanent levels threatened and indeed affected product quality, sales revenues and firm performance negatively forcing management to reach some agreements with the trade unions. These opposing results had explanations in the fact that while for lay-offs people left and were replaced by new ones who accepted lower wages and fringe benefits and thereby not affecting worker satisfaction, more temporary terms attracted and favoured untrained staff that led to sub-standard work hurting product quality and the revenue base of the firm subsequently. This would tend to suggest that in the lowest paid industries that also used manual skills, cutting wages and fringe benefits through layoffs and fresh recruitment could boost profitability; but increasing temporariness in jobs that required training would harm sales revenues and profitability and thereby putting a limit to how motivation would be manipulated to improve firm performance after privatisation.

4. Conclusions

- This paper set out to investigate the differences in motivation in both the public and private sectors by looking at motivation before and after privatisation. Before privatization, both salaries and wages on one hand and fringe benefits on the other were determined by the nature of ownership as well as industry type on the other hand. In purely SOEs, the determination of workers’ conditions was political. Purely SOEs were lavish in granting salary and other benefits to staff explained by state ownership and existing trade unions. FDI, however, tended to ignore the idea of collective agreement and fluffed the trade unions and their restrictive working practices such as working 8 hours a day. Bad conditions in FDI firms always resulted into strikes with varying intensities with casualties to either the crop or management staff. The salary and other benefits also differed among industries, the poorest being recorded in the textile, followed by the plantation-based industries, and utilities last [Okuku, 1995:14]. These SOEs’ lavish conditions of service changed drastically after privatization from permanent and pensionable (PP) to temporary and retrenchable (TT). After privatization, the new buyers cunningly increased salaries for managerial, technical and clerical staff on paper. Practically, however, they recruited most staff to high positions as group employees who did not enjoy negotiated terms. In addition, PSOEs laid off group employees earning shs. 300, 000= and replaced them with those willing to work for shs. 100, 000= per month. The terms casual, temporary, and contract in PSOEs and meant ‘daily but continuous,’ ‘six months to one year,’ and ‘one to three years’ respectively. This was made possible by high unemployment levels in the country. This resulted into falling wage-bill as well as product quality in the tea and sugar sectors. With respect to benefits, after privatization, these depended on industry and profitability unlike before privatization.

Endnotes

- 1. Interview with Mr. Mukasa, Secetary General of NUCCPTE at, Kisekka Market, on Monday, 25th April 20062. Op cit, Mr. Bahingana3. Interview with Mr. Mukasa, Secetary General of NUCCPTE at, Kisekka Market, on Monday, 25th April 20064. ………, (2002), “Museveni Opens East African Assembly,” New Vision, Tuesday, January 22. 5. s. 3, Statute 10/19936. Statute 10/1993 s.72 (2) (c) (iii-iv)7. Interview with Edward Rubanga, Trade Unionist with URWU, Sunday 28th September 2003 in Kampala at CBR8. Statute 10/1993 s.72 (2) (c) (iii-iv)9. s. 3, Statute 10/199310. Crown Bottlers Company Limited, (1999), ‘Change of Pay periods,’ Letter from the Human Resources Manager Mr. Ian Tailor dated 10th May 11. Crown Bottlers Company Limited, (1999), Substantive Agreement between Crown Bottlers Company Limited and UBTAWU, 1st May, Kampala.12. Interview with Mr. Bahingana at Delhi Garden, Plot 1, Old Kampala Uganda, on Thursday, 21st April 200613. Interview with Mr. Apollo Himanyi, UEAWU Administrator, on 9th May 200614. Op cit,Mr. Wandera15. Op cit,Mr. Wandera16. Statute UP&TC, s.52 (1) a17. s.52 (1) a, Statute UP&TC18. s.52 (2), Statute UP&TC19. s.11 (2), Statute22/196520. s.11 (1), Statute22/196521. s. 19, Statute 9/199322. s. 23 (b) Statute 13/199323. Op cit, Mr. Baliraine24. Crown Bottlers Company Limited, (1999), ‘Change of Pay periods,’ Letter from the Human Resources Manager Mr. Ian Tailor dated 10th May 25. Crown Bottlers Company Limited, (1999), Substantive Agreement between Crown Bottlers Company Limited and UBTAWU, 1st May, Kampala.26. The PERDS 9/1993 and its subsequent amendments classified enterprises in five groups. The first group included those enterprises to be fully owned by government. These were economically viable, politically sensitive, provided essential services and were tied to projects that had huge external funds acquired by government for their rehabilitation. The second category (class II) consisted of enterprises in which government held majority shares. They included viable, politically sensitive and that provided essential services but differed from the first group by the fact of rehabilitation costs funded by foreign donors. The third category (Class III) included enterprises where government was to hold minority shares. These were viable economically and high cost projects that attract private equity and technology if government were to take up some equity holding in them. The fourth (Class IV) and fifth (Class V) categories included those enterprises government was to sell and liquidate respectively. The fourth category included those enterprises that were economically viable and commercially oriented while the fifth category included the economically unviable and defunct or non-operating SOEs. Since, 1993, however, government has been shifting enterprises as it wishes. The criteria of starting with small ones, to medium and later to large seem to have been at work in Uganda. It can be noted that the in the early privatisations before 1996, trade Unions and their members were not involved in the process and even when some attended they process was very academic for trade unionists to follow.27. Uganda Posts Limited (UPL), Uganda Telecom Limited (UTL), the Post Bank Uganda Limited or the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) in case of UP & TC or Uganda Electricity Distribution (UEDCO), Uganda Electricity Generation Company (UEGCO) and the Uganda Electricity Company (UE.CO) in case of UEB28. s. 89 (1), Uganda Communications Act 8/199729. s. 89 (2), Uganda Communications Act 8/199730. s. 90 (1), Uganda Communications Act 8/1997 31. s. 90 (2), Uganda Communications Act 8/199732. s. 90 (3), Uganda Communications Act 8/199733. s. 90 (4 & 5), Uganda Communications Act 8/199734. Interview with Mr. Bahingana at Delhi Garden, Plot 1, Old Kampala Uganda, on Thursday, 21st April 200635. Op cit, Mr. Bahingana36. Interview with Mr. Apollo Himanyi, UEAWU Administrator, on 9th May 200637. Op cit, Mr. Bahingana38. Op cit,Mr. Wandera

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML