-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

July, 2012;

doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20120001.27

Participate In Boycott Activities Toward Danish Products From The Perspective Of Muslim Consumer

Mohammed Sami Albayati , Nik Kamariah Nik Mat , Anwar Salem Musaibah , Hassan Saleh Aldhaafri , Ebrahim Mohammed Almatari

Othman Yeop Abdullah graduate school of business, University Utara Malaysia, Kedah, 06010, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Mohammed Sami Albayati , Othman Yeop Abdullah graduate school of business, University Utara Malaysia, Kedah, 06010, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purpose of this study is to examine and ascertain the effects of integrative motivation on the willingness to participate in boycott activities toward Danish products from the perspective of Muslim consumer. Consumer boycotts is a worldwide and historic phenomenon in modern society. The religious boycotting campaigns have proved to be significantly damaging to international companies. From the literature, four effects of motivation on boycott participation are identified. Each variable is measured using 5-point interval scale: Animosity (4 items), efficacy (4 items), product judgment (5 items), prior purchase (4 items) and boycott participation (5 items). Using primary data collection method, 150 questionnaires were distributed to target respondents of post-graduate and under-graduate students of a university in North Malaysia. The responses collected were 121 completed questionnaires representing 80.67 percent response rate. The data will be analyzed using Structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 16. Confirmatory factor analysis of measurement models indicate adequate goodness of fit after a few items was eliminated through modification indices verifications. This study has established six direct causal effects. The findings are discussed in the perspective of Malaysian boycott participation. Overall, the results suggested that the perception of the above four construct and other two important once (efficacy) (β= 0.595, CR=5.758, P<0.001), and (product judgment) (β= 0.617, CR=4.147, P<0.001) Are significantly related and may influence the boycott activities directly or indirectly.

Keywords: Boycott, Animosity, Efficacy, Prior Purchase, Product Judgment, Denmark

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The term boycott is an attempt to change or punish a company’s unacceptable behavior. It represents an attempt of one or more than one individual to achieve their purpose by discouraging consumers from making purchases from a certain company[1]. The word itself stems from a person named Charles C. Boycott, an Englishman who was ostracized from society in 1880 for negating the decrease of land rents. On the other hand, boycotting as a forced action for prevention of certain consumptions of goods in the market has been carried out for a certain number of years and more importantly, certain individuals advocate for its enforcement when they perceive that a certain country or a certain company’s act is unbecoming[2],[3],[4]. Boycotts are also enforced as a strategic technique to change a company’s activities[2],[5],[6].Boycotts are enforced to generally clarify either a political, social or ethical statement against a company in order to force it to change or discard an action that is considered to be immoral or controversial[7]. Generally speaking, boycotts are dependent on the participation of the large population of consumers who are aware of the social ills that the sale, the manufacture or the marketing of a product entails. The target customers make the significant part of the market as they sway the direction of sales of products – they are willing to pay higher for a socially responsible product or switch to alternatives if they deem the product to be unworthy of social acceptance.Boycotts are often successful in carrying out the aim of controlling unbecoming behavior from either a company or a country mainly owing to the well-known boycotts that have paved the way for comparatively powerless entities[4] like the Montgomery Bus boycott, the California Grape boycott 1965-1970[2] and the Shell boycott with a participation rate of a mere 6% but eventually halted the company from sinking its Brent Spar Oil Platform at sea[8].During the past century, Denmark and some other European countries have carried out a constant assault on the religious and moral aspects of Islam which resulted in the boycotting of Danish companies throughout the Muslim world. The scenario is such that religious animosity and the boycotting campaigns dedicated to it have been known to create havoc in international companies. The recent controversy regarding Danish cartoons that some Muslims regarded as degrading and offensive to Islam, the Islamic countries initiated the boycott by boycotting the Danish company Arla which in turn earned a counter boycott from the Western consumers who considered the first boycott unjust[9].In the context of Malaysia, three months prior to assuming high office, Tun Mahathir Mohammad, started a boycott campaign against British products called the Buy British Last Policy. Tun Mahathir attributed the boycott to what he referred to as the British neo-colonial policies and accusations against Malaysia. The policy was in remained enforced until 1983[10]. Since then, the Malaysian society has gone through significant economic and social transformations that have reformulated the understanding and enforcement of boycotting[11].In sum, this only goes to show that a smorgasbord of political motivations including patriotism, and animosity impact consumer behavior[12],[13]. Along these lines, the main objective of the present study is to study and determine the impact of integrative motivation upon the Muslim consumers’ inclination to participate in boycotting Danish products through the analysis of the following variables: animosity, efficacy, product judgment and prior purchase.

2. Animosity and Boycott

- According to several researchers[12],[13], there are several political reasons such as patriotism and animosities that impact consumer behavior. A boycott is an attempt to change or punish the unseemly conduct of a business by one or more entities through the discouragement of selected purchases from the market[1]. A look at literature reveals that several researchers have investigated the consumers’ motivations behind this action (e.g.[4],[7]). Moreover, scholars have found that consumer boycott is retaliation to the exchange of the industrial unit.The boycotting campaign against Denmark’s Arla Foods (AF) was considered to be a part of the religious animosity that developed within the Muslim societies[12], owing to the Danish newspaper, Jyllands Posten’s contents which depicted the Prophet Mohammad in September of 2005. Following the publication of the cartoons, AF boycott campaign was initiated in 2006 and on the first five days of the campaign, the company registered 60% losses in its market share[14]. Despite the Fatwa (a religious statement commanding obeisance) enforced by the International Support of the Prophet Conference in Bahrain which clearly specified AF’s exemption to the boycott, AF has failed to improve its market share in Saudi Arabia, where its production conveniences are located. It is noteworthy that this particular instance is history repeating itself in another part of the world. Prior research conducted by[15] revealed that the Japanese war atrocities left an indelible impression on the purchasing behavior of Chinese consumers of Japanese products.Klein, Ettenson, and Morris[15] investigated the impact of consumer animosity upon a foreign country’s products and revealed that consumers are inclined to pass up on products that take part in armed operations, or act in a serious or controversial political or economic behavior. In addition,[3],[4] stated that consumers tend to overlook the superficial costs that they have to spend on the available substitutes and they stressed the fact that easily substitutable products are likely to be boycotted. Nevertheless, it has been noted that within the purview of regional animosities, national animosities run on the same model and works through discouraging the buying of certain products manufactured in regions opposed to the market[16] and through manipulating the preferences of the area[17].In a related study,[18] determined whether consumers are sure of their power to impact and assist in the required change. The incentive behind the boycott is referred to as the high perceived efficacy which according to[7] is the consumer’s belief that each boycotter can make a difference in the outcome of the boycott and a few of them believe that other consumers will be inclined to participate in the boycott campaign.Furthermore, consumer animosity is revealed to impact the motivation of consumer to buy which can be stated as, “the beliefs held by consumers about the appropriateness, indeed morality, of purchasing foreign-made products”[13]. Several authors reveal that animosity is distinct constructs[16],[19],[20] possessing distinct impact on preferences of foreign products.

2.1. Efficacy and Boycott

- According to Friedman[1] a boycott is an attempt to change or withdraw or even punish the controversial behavior of a society which implies an attempt of one or more entities to carry out their objectives by discouraging consumers from making purchases of certain products in the market. Current studies reveal some of the motivations of consumers behind the boycott (e.g.[4, 7]). Some scholars revealed that consumer boycott has been a response to the relocation of a certain factory.Prior research has emphasized the importance of social impact upon the participation in boycotts, for instance,[7]. Most consumers state their loyalty to boycott while others only participate if they are sure that the objective will be achieved through it. These social influences can be analysed through the Diffusion Theory as proposed by[21]. The question that arises is, who are the innovators to start a boycott, even when the impact of it is low? It is presumed that motivation may convince other individuals to participate in the boycott. In case of low probability of success, the initial boycotters are considered to be more idealistic than followers as they strive harder for self-improvement.Similarly, Sen[7] considered perceived efficacy as the level to which individual participants believe that the boycott being enforced can significantly contribute to the success of the unanimous goal while[3] explains the exaggerated view of the boycott’s usefulness which may be the reason why people often participate in boycotts even when the target entity will not notice.Eventually, the more participants to the boycott the more likely a social force will result. Therefore, it can be assumed that an increase in participation would lead to an approximate increase in real participation. It is also assumed that participation would act as a moderating affect on the estimated self-improvement variables. Moreover, an approximate increase in participation could modify its perception.

2.2. Prior Purchase and Boycott

- Prior purchase has a place in the model owing to the fact that individuals who purchased French goods across varying categories prior to the boycott are expected to participate in a higher level of boycott. In turn, prior purchase is assumed to be a function of consumer product judgments because those having low motivation and who believe that French products are of high quality are presumed to be French products purchasers prior to the boycott[22].

2.3. Product Judgment and Prior Purchase

- Majority of prior studies assessed the consumers’ product judgment and inclination to purchase while ignoring actual product ownership[16],[20],[23],[24]. The pioneering researchers to first tackle the direct impact of products’ country of origin upon purchasing decisions, independent of product judgments is[15]. They revealed that customers’ judgments regarding products are impacted by their experiences of prior purchase and customers tend to give priority to disregarding products judging from their prior intentions against them. In sum, the consumers’ opinions and judgments against particular products will impact their purchase decisions.

3. Data and Method

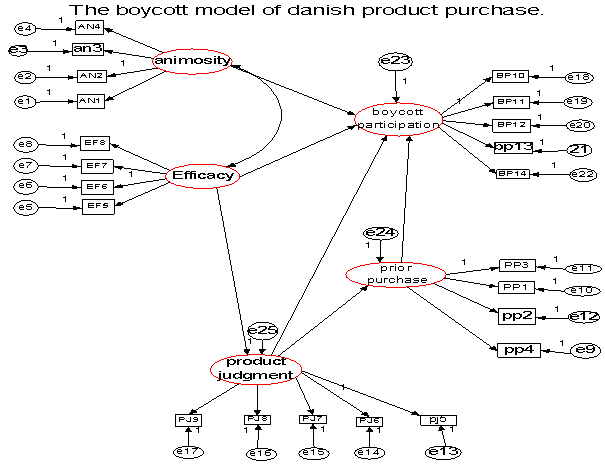

- The present study attempts to determine the boycott participation predictors as elaborated in Figure 1. The research framework reveals that animosity and efficacy have a direct link to boycott participation. Two exogenous variables are incorporated in the research; animosity and efficacy while three endogenous variables are considered with two mediator variables and one dependent variable; prior purchase, product judgment and boycott participation respectively.

| Figure 1. The proposed model of boycott participation |

4. Findings

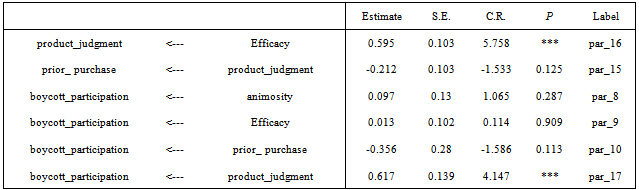

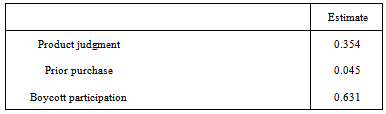

- The results of the measurement model test determine how well the indicators capture their specified constructs[25]. The results of the analyses suggested that the fit of all of the measurement models was adequate.The x2/DF ratios (CMIN/DF) were lower than or close to the suggested threshold (i.e. 5 or less)[26]. The root mean square errors of approximation (RMSEA) values were lower than or equal to 0.010. In addition, all other indices (i.e. Comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and normed fit index (NFI) estimates) were greater than the recommended 0.90 threshold throughout the fit analysis for all measurement models. The outcome is summarized in (Table 2). Two hypotheses were supported i.e. efficacy and product judgment; product judgment and boycott participation. This implies that when consumers have negative perception of a product, the chances of a boycott is higher.

|

|

5. Conclusions

- Boycotts are enforced to generally clarify either a political, social or ethical statement against a company in order to force it to change or discard an action that is considered to be immoral or controversial[7]. Boycotts are dependent on the participation of the large population of consumers who are aware of the social ills that the sale, the manufacture or the marketing of a product entails. The target customers make the significant part of the market as they sway the direction of sales of products – they are willing to pay higher for a socially responsible product or switch to alternatives if they deem the product to be unworthy of social acceptance.Overall, the results suggested that the perception of the above four constructs and other two important ones (efficacy and product judgment) are significantly related and may influence the boycott activities directly or indirectly.

References

| [1] | Monroe Friedman, "Consumer Boycotts in the United States, 1970-1980: Contemporary Events in Historical Perspective", Journal of Consumer Affairs, vol.19, no.1, pp.96-117, 1985. |

| [2] | Monroe Friedman, "Consumer Boycotts", Routledge, New York, NY, 1999. |

| [3] | Andrew John, Jill Klein, "The Boycott Puzzle: Consumer Motivations for Purchase Sacrifice". Manage Sci, vol.49, no.9, pp.196-209, 2003. |

| [4] | Jill Gabrielle Klein, N. Craig Smith , Andrew John, "Why we boycott: consumer motivations for boycott participation", Journal of Marketing, Vol. 68 No. 3, pp. 92-109, 2004. |

| [5] | David P. Baron, "Private Politics", Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, no.12, pp.31-66, 2003. |

| [6] | Randy Shaw, "The Activist’s Handbook", Berkeley: University of California Press, (1996). |

| [7] | Sankar Sen, Zeynep Gurhan-Canli, Vicki Morwitz, "Withholding Consumption: A Social Dilemma Perspective on Consumer Boycotts", Journal of Consumer Research, vol.28, no.December, pp.399-417, 2001. |

| [8] | Clouder Scott, Harrison Rob. The effectiveness of ethical consumer behavior. In: Harrison Rob, Newholm Terry, Shaw Deirdre, editors. The Ethical Consumer. London: Sage; 2005. p. 89–106 |

| [9] | Glazer, Kanniainen, Poutvaara, "Firms’ Ethics, Consumer Boycotts", in Proceedings of 2008 CES ifo conference on ethics and economic, pp. 2, 2008. |

| [10] | Michael Leifer, "Dictionary of the Modern Politics of South-East Asia", London/New York: Routledge, 1995. |

| [11] | Johan Fischer , "The Moderate and the Excessive: Malay Consumption in Suburban Malaysia", PhD Dissertation, Roskilde University, 2005. |

| [12] | Petra Riefler, "A Diamantopoulos, Consumer Animosity: A Literature Review and a Reconsideration of Its Measurement", Int Mark Rev, vol.24, no.1, pp.87–119, 2007. |

| [13] | Terence A Shimp, Subhash Sharma, "Consumer Ethnocentrism: Construction and Validation of the CETSCALE", J Mark Res, 24, no.3, pp.280-289, 1987. |

| [14] | Ibrahim Abosag, "The Boycott of Arla Foods in the Middle East", pp.3-30, 2009, In Introduction to Marketing, Prentice Hall. |

| [15] | Jill Gabrielle Klein, Richard Ettenson and Marlene D. Morri, "The Animosity Model of Foreign Product Purchase: An Empirical Test in the People's Republic of China", Journal of Marketing, 62, no.January, pp.89-100, 1998. |

| [16] | Wolfgang Hinck, "The Role of Domestic Animosity in Consumer Choice: Empirical Evidence from Germany", Journal of Euromarketing, vol.14, no.1/2, pp.17, 2004. |

| [17] | Terence A. Shimp, Tracy H. Dunn, Jill G. Klein, "Remnants of the U.S. Civil War and Modern Consumer Behavior", Psychology and Marketing, vol.21 no.February, pp.75-91, 2004. |

| [18] | Karin Braunsberger, Brian Buckler, "What Motivates Consumers to Participate in Boycotts: Lessons from the Ongoing Candian Seafood Boycott", Journal of Business Research, vol.64, pp.96-102, 2011. |

| [19] | Klein JG, Ettenson R, "Consumer animosity and consumer ethnocentrism: an analysis of unique antecedents", Journal of International Consumer Marketing, vol.11, no.4, pp.5-24, 1999. |

| [20] | Terrence H Witkowski;, "Colonial Consumers in Revolt: Buyer Values and Behavior during the Nonimportation Movement, 1764-1776", Journal of Consumer Research, vol.16, no.2, pp.216-226, 2000. |

| [21] | Everett M Rogers, "Diffusion of Innovations", 5th ed., Free Press, New York, 2003. |

| [22] | Richard Ettenson, Jill Gabrielle Klein, "The Fallout from French Nuclear Testing in the South Pacific: A Longitudinal Study of Consumer Boycotts", International Marketing Review, vol.22, no.2, pp.199-224, 2005. |

| [23] | Kesić, T., Piri Rajh, "The Role of Nationalism in Consumer Ethnocentrism and the Animosity in the Post-War Country", in Proceedings of 2005 The 34th European Marketing Conference, Milan, 2005. |

| [24] | Nijssen, E.J. , Douglas, S.P, "Examining the Animosity Model in a Country with a High Level of Foreign Trade", International Journal of Research in Marketing, vol.21, 23-38, 2004. |

| [25] | kenneth a. bollen, "Structural Equations with Latent Variables", Wiley, New York, 1989. |

| [26] | Wheaton, B.; Muthen B; Alwin D F; Summers G F, "Assessing Reliability and Stability in Panel Models", Vol. 8, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, 1977. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML