-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

July, 2012;

doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20120001.20

The Direct Effects of Halal Product Actual Purchase Antecedents among the International Muslim Consumers

Khairi Mohamed Omar , Nik Kamariah Nik Mat , Gaboul Ahmed Imhemed , Fatihya Mahdi Ahamed Ali

Othman Yeop Abdullah Graduate School of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, 06010, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Nik Kamariah Nik Mat , Othman Yeop Abdullah Graduate School of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, 06010, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study investigates the direct effects of purchase intention and consumer confidence towards halal product actual purchase based on Theory of Planned behavior (TPB). Four antecedents of actual purchase are identified: purchase intention (4 items), consumer confidence (7 items), perceived behavioral control (7 items), subjective norm (7 items) and actual purchase (8 items). Using primary data collection method, 200 questionnaires were distributed to target respondents comprising of international graduate students studying at five universities in Malaysia. The responses collected were 120 completed questionnaires representing 60% percent response rate. The data were analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) via AMOS 18. This study proposes four direct causal effects and two mediating effects in the structural model. The findings indicate that the TPB is a valid model in the prediction of actual purchase of halal products. Goodness of fit for the revised structural model shows adequate fit. Two of the hypotheses are substantiated: subjective norm is found to be positively related to confidence (β= 0.400, CR=2.302, P<0.021), and perceived behavioral control was also positively related to the intention (β= 0.831, CR=3.958, P<0.001). The paper extends the understanding of TPB to newly emerging contexts such as halal products usage intentions and confidence.

Keywords: Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Perceived Behavioral Control, Subjective Norm, Purchase Intention, Halal Knowledge, Consumers’ Confidence, Halal Product, Actual Purchase

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Today, the halal logo (حلال) on products is no longer just purely a religious issue. It is becoming a global symbol for quality assurance and lifestyle choice in the realm of business and trade[1]. Halal is an Arabic term meaning “permissible”. In English, it most frequently refers to thing that is permissible according to Islamic law. In the Arabic language, it refers to anything that is permissible under Islam[2]. It is usually used to describe something that a Muslim is permitted to engage in, e.g. eat, drink or use. The opposite of halal is haram, which is Arabic for unlawful or prohibited. Accordingly, Halal products are those that are Shariah compliant, i.e. do not involve the use of haram (prohibited) ingredients, exploitation of labor or environment, and are not harmful or intended for harmful use. The realm of halal may extend to all consumables such as toiletries, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, etc. In addition, it encompasses a wide range of industry sub-sectors with elements of religious, political and financial dimension in it.Muslim consumers are very similar to any other consumer segments, demanding healthy and quality products, which must also conform to Shariah requirements[3]. The halal certificate or logo not only guarantees Muslims what they consume or use is according to the Islamic laws but also encourages manufacturers to meet the halal standards[4]. Thus, halal certificate can play an important role to assure consumers that the product has got the necessary conditions of halal product.The expanding halal products market represents a significant opportunity for international products companies, not only in Muslim countries but also in Western markets with significant and growing Muslim populations among whom halal observance is on the increase[5]. According to Alam and Sayuti[6], there are altogether more than two billion Muslim populations in the world spreading over 112 countries, across diverse regions such as Organization of Islamic Conference Nations (1.4 billion), Asia (805 million), Africa (300 million), Middle East (210 million), Europe (18 million), and Malaysia (16 million) (www.mida.gov.my). The global halal market is estimated to be worth US$580 billion a year. According to global group High Beam Research, cited in the Halal Journal[7], the current estimated value of the total halal market is US$150 billion a year, but this has the potential to rise to US$500 billion by 2010, driven by the increasing value and diversity of the consumer market, combined with strong demographic trends across the world[8]. Extra levels of quality certification have attracted an unprecedented demand for Muslim and non-Muslim consumers[9]. This means that Halal products and services should be developed and promoted for the Ummah rendering the halal industry as a new dynamic source of economic growth.On the other hand, Halal is essentially an Islamic phenomenon, so, it is good to highlight the benefits of Islam to all mankind. It is inevitable that Muslim become more particular on the type of products and services that they use as they have become more knowledgeable of their religion[10].Thus, the objective of this study is to examine the causal relationships of several antecedents of actual purchase of Halal product based on TPB model. In particular, this study has four specific objectives: 1) to identify the direct influence of perceived behavior control and subjective norm on purchase Intention; 2) to identify the direct influence of perceived behavior control and subjective norm on consumer confidence; 3) to identify the direct influence of purchase intention on actual purchase; 4) to identify the direct influence of consumer confidence on actual purchase; This paper is structured as follows. First, we review the marketing literature on the antecedents of actual purchase: purchase intention, consumer confidence, perceived behavior control, subjective norm and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Next, we present the research framework, methods, measures and findings. Finally, the results were discussed in terms of its contribution to the upgrading of manufacturers and marketers and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature Review

- Ajzen and Fishbein[11] define actual purchase behavior as an “individual's readiness and willingness to purchase a certain product or service”. Past studies have identified several predictors of actual behavior: intention, intention and perceived behavior control[12],[13],[14],[15], subjective norm[16].

2.1. Theoretical Underpinning of Study

- The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), first proposed by Ajzen[11] suggests that intention is determined by three factors: attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control. Behaviour, on the other hand, is determined by the individual’s intention to perform the behavior[17]. This study adds the consumer confidence as an immediate antecedent of actual purchase of halal product[30]. Each relationship with its criterion variable is discussed subsequently.

2.2. Purchase Intention and Actual Purchase

- Elbeck and Mandernach[18] described the readiness of potential customers in terms of purchase intention about a product. This means purchase intention is a prediction about consumers’ attitudes. Ajzen and Fishbein[19], define intention as a person's location on a subjective probability dimension involving a relation between himself and some action. In addition, Armitage and Conner[20] stated that intention is recognize as the motivation for individuals to engage in a certain behavior. Purchase intention can affect the buying decision of customers in the future. Moreover, based on various previous theories, purchase intention can be considered as the predictor of future purchase decisions[19]. Furthermore, according to the TPB model, behavioural intention is an immediate antecedent of behaviour[21]. Thus, Behavioral intention is defined as the individual's subjective probability that he or she will engage in that behavior[19].

2.3. Subjective Norm and Purchase Intention

- In the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the second determinant of behavioral intention is subjective norm. Subjective norm is defined as ‘‘the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior’’[22]. Subjective norm is the function of how a consumer’s referent others (e.g., family and friends) view the regarding behaviour and how motivated the consumer is to comply with those beliefs[23]. Theory of planned behavior (TPB) holds that subjective norm is a function of beliefs. Beliefs play important roles in forming the intention of customers[24]. Beliefs that underlie the subjective norm are called normative beliefs. Thus, if a person believes that the most important referents or individuals to them think that the behavior should be performed, then the subjective norm should influence the intention of the person to perform the behavior in question. For instance, if consumers believe that significant others think Halal products are good; consumers will have more intention to buy these products. Therefore, this shows that subjective norm influences intention to perform a particular behavior. Leo and Lee[25] support the definition from TPB by defining subjective norm as "one's perception of whether people important to the individual think the behavior should be performed". In previous studies of buying intention and behavior toward organic food, the role of subjective norms was not clear, especially with regard to their effect in forming the behavior[17]. Magnusson et al.[26] did not use subjective norms in their research whereas Sparks and Shepherd[27] did, but the significance of this factor is not strong.

2.4. Perceived Behavior Control and Purchase Intention

- Perceived behavior refers to the degree of control that an individual perceives over performing the behavior[28]. In addition, according to[22], "perceived behavior control is the extent to which a person feels able to engage in the behavior". Moreover, according to Ajzen[22] perceived behavior control can account for considerable variance in behavioral intention and actions. Providing that when people believe they have more resources such as time, money and skills their perceptions of control are high and hence their behavioral intentions increase[29]. Therefore, it is assumed that intention to purchase Halal is higher when consumers perceive more control over buying these products.

2.5. Consumer Confidence and Actual Purchase

- Muslim consumers do not have other means to determine whether the manufactured products are Halal or not, except by referring to the halal logo that has been entrusted in the packaging of the products[30]. Badari et al.[31] say that average respondent from the study states that authentication of organic food labels mean, trademarks and logos which means confirmed, guidelines, standards and regulations. This means that logos are important resources for the clearance of consumer confidence on products. Thus, Halal certification provides for greater consumer confidence as it allows consumers to make an informed choice on their purchase[32]. However, the lack of enforcement in monitoring the usage of certified Halal food has caused the public to question the validity of some products that were claimed to be Halal[30].

2.6. Subjective Norm and Consumer Confidence

- Athiyaman[33] pointed out that the subjective norm refers to one's perception of social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior under consideration. Consumers’ confidence in halal product is shaped by numerous factors. These include advertising, information on product ingredients and announcements, various halal claims, and warnings on non halal product products which carry a halal logo[34]. Consumer behaviour is very complex and it is determined by emotions, motives and attitudes[35]. Under the theory of reasons action (TRA) attitudes and belief play a fundamental role in a consumer’s behaviour because they determine consumer disposition to respond whether positively or either negatively to an institution, person, event, object or product[35],[36]. According to the researchers, the link between the altitudinal characteristics and behaviour suggests that consumers are more likely to engage in the behavior they feel to have control over and prevented from crying out behavior which they feel they have no control over. Meanwhile, control factors such as the level of confidence and the level of religiosity may facilitate or inhibit the decision in purchasing halal products.

2.7. Perceived Behavior Control and Consumer Confidence

- Perceived behavioral control reflects beliefs regarding the access to resources and opportunities needed to perform a behavior[22].The perception of volitional control or the perceived difficulty towards the behaviour will affect intent[37]. Unless control over behaviour exists, intentions will not be sufficient as the predictor of the behaviour[38]. Where, perceived behavioral control is defined as an individual’s confidence that he or she is capable of performing the behaviour[21]. According to Ajzen[21], perceived behavioral control has two aspects, (1) how much a person has control over behavior, (2) how confident a person feels about being able to perform or not perform the behavior. As an illustration, when an individual feels that he/she has more control about making halal products purchases, the more likely he/she will be to do so.

3. Methodology

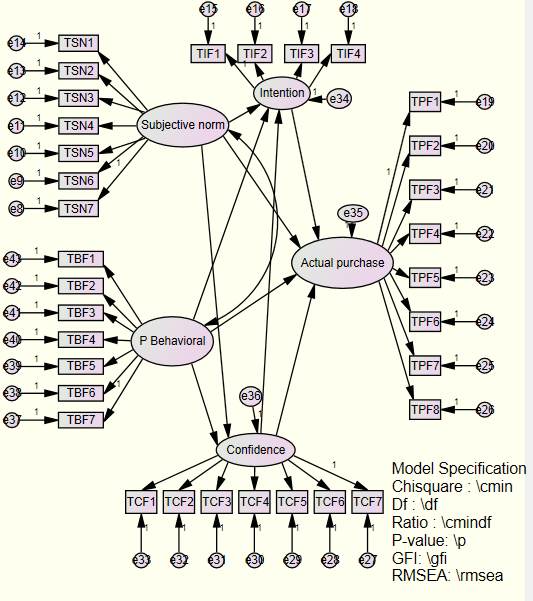

- When this research framework is translated into the hypothesized model (see Figure 1), the manifesting variables are drawn with the error terms for each latent variables. The two exogenous variables of perceived behavioral control and subjective norm each one contains seven manifesting (observed) variables.

| Figure 1. Hypothesized Model |

3.1. Sampling

- The sample in this study was the international Muslim consumers in several universities in Malaysia, University of Utara Malaysia (UUM), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM), and Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM). Respondents consist of the student’s, lecturer, and administrative staff of these universities in Malaysia. It has distributed 200 questionnaires to target respondents. Finally, 120 respondents completed and returned the questionnaires, which represents about 60% response rate.

3.2. Instrument

- For examining the questions of study and testing the hypotheses, this study used questionnaire, as a medium to obtain the data needed, which was developed depending upon the previously instrument as follows: perceived behavioral control, subjective norm, purchase intention and actual purchase measures were adopted from[22] and[39]. While consumers’ confidence measures were adopted from[30].The questionnaire was divided into 2 sections. The first part consists of 3 questions about the respondents’ demographic characteristics and personal information which use ordinal and nominal scale such as age, gender and education. A part 2 consists of 7-point Likert scale to evaluate the level of agreement of respondents with the 4 factors considered: consumer confidence (7-item), subjective norm (7-item), purchase intention (4-item) and actual purchase (8-item).

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

- The data was analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), AMOS 18 version. Confirmatory factor analysis of measurement models indicate adequate goodness of fit after a few items was eliminated through modification indices verifications.

4. Findings

4.1. Demographic Profile of the Respondents

- The respondents’ ages ranged from nineteen to forty-six years old averaging 31 years old. The male respondents were 86.9% and the female respondents were 13.1%. Most of The respondents were full-time students (54.2%) followed by part-time students (25.2%) and lecturers (20.5%). Their education varies from Master’s degree (48.6%), Bachelor’s degree (18.7%), PhDs (30.8%) and others were (1.9%).The findings of this study indicated that the TPB is a valid model in the prediction of the consumers’ confidence and halal product purchases’ intention to choose halal products. Where; subjective norm was found to be positively related to confidence, with confidence being the more influential predictor (β= 0.400, CR=2.302, P<0.021), perceived behavioral control was also positively related to the intention to choose halal products at (β= 0.831, CR=3.958, P<0.001). The paper extends the understanding of TPB to newly emerging contexts such as Halal products usage intentions and Confidence.The finding supports six hypotheses (H2, H4, H5, H6, H7, and H10) and rejects four hypotheses (H1, H3, H8, H9). Consumers’ confidence and purchase intention were found to be mediators.

4.2. Goodness of Fit of Structural Model

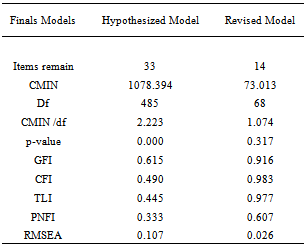

- To arrive to the structural model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on every construct and measurement models. The goodness of fit is the decision to see the model fits into the variance-covariance matrix of the dataset. The CFA, measurement and structural model has a good fit with the data based on assessment criteria such as Goodness Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Root mean square Error Approximation (RMSEA) (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). All CFAs of constructs produced a relatively good fit as indicated by the goodness of fit indices such as CMIN/df ratio (<2); p-value (>0.05); Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) of >0.95; and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of values less than 0.08 (<0.08) (Hair et al., 2006). Finally, the goodness of fit of generated or revised model is achieved. GFI of revised structural model is 0.916; Root mean square Error Approximation (RMSEA) is 0.026; p-value is 0.317, cmindf ratio is 1.074. (See Table 1).

|

5. Conclusions

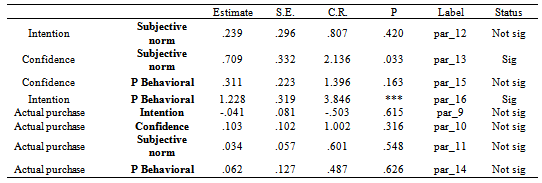

- This study has established four direct causal effects: 1) perceived behavioral control and halal product purchase intention; 2) subjective norm and consumers’ confidence; 3) halal product purchase intention and halal product actual purchase; and 4) confidence and halal product actual purchase. Interestingly, this study also manages to present first time findings on two mediating effects: 1) halal product purchase intention mediates the relationship between perceived behavioral control and halal product actual purchase; and 2) consumers’ confidence mediates the relationship between subjective norm and actual purchase. (See table 2)

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to thank Prof Dr. Nik Kamariah Nik Mat and Sukma Pea for their helpful comments and assistance on an earlier version of this paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML