-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

July, 2012;

doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20120001.17

Entrepreneurial Intentions among Technical Students

Umi Kartini Rashid 1, Nik Kamariah Nik Mat 2, Rabiatul Adawiyah Ma’rof 2, Juzaimi Nasuredin 1, Fitriah Sanita 2, Muhamad Faiz Mohamed Isa 2

1Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Parit Raja, Batu Pahat, 86400, Malaysia

2Othman Yeop Abdullah Graduate School of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, 06010, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Umi Kartini Rashid , Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Parit Raja, Batu Pahat, 86400, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of this study is to determine the relationships between professional attraction, entrepreneurial capacity and entrepreneurial experience toward entrepreneurial intention among the students enrolled in technical courses of a university in the South of Malaysia. All variables are measured from developed instrument using 5-point interval scale: professional attraction (6 items) and entrepreneurial capacity (5 items) as the exogenous variable, while entrepreneurial experience 3 items) and entrepreneurial intention (6 items) as endogenous variables. Questionnaires were distributed to 129 students, based on random sampling method selected from various races and genders, for the purpose of data collection. The data was analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The result shows that the goodness of fit indices of structural equation model are achieved at GFI=0.951, P-value=0.249, RMSEA=0.036 and ratio (cmin/df) =1.163. The finding supports three significant direct effects in the revised model, thus supporting the hypotheses regarding professional attraction is positively related to entrepreneurial intention (β=0.648, CR=2.324, p<0.05), professional attraction is positively related to entrepreneurial experience (β=0.407, CR=2.270, p<0.05), and entrepreneurial capacity is positively related to entrepreneurial experience (β=0.597, CR=2.245, p<0.05). The structural model explains 93.1 percent variance in entrepreneurial intention. The result is discussed in the perspective of technical students’ intentions toward entrepreneurship.

Keywords: Entrepreneurial Capacity, Entrepreneurial Experience, Entrepreneurial Intention, Professional Attraction, Technical Students

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Based on[1], entrepreneurship can provide a source of income when an economy cannot yet supply enough jobs or other alternatives for generating wages or salaries, providing positive social value is in place.[2] found that background of non-economic and business education significantlyinfluenced the intentions to be an entrepreneur in the future. The intention to start up would be a previous and determinant element towards performing entrepreneurial behaviours [3] ,[4]. In addition, intentions toward behaviour would be the single best predictor of that behaviour[5],[6].Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to determine the factors influence “entrepreneurial intention” among the technical students namely: professional attraction, entrepreneurial capacity and entrepreneurial experience. The existing entrepreneurship literature suggests that the nature of the experience (success or failure) influences entrepreneurs’ re-entry intentions[7].

2. Literature Review

- Entrepreneurial intention is defined as the efforts of a person to carry out entrepreneurial behaviour[8].

2.1. Professional Attraction and Entrepreneurial Intention

- Professional attraction is defined as the extent to which individuals hold a positive or negative assessment of personal about being an entrepreneur[9]. Besides prior studies which support the general notion that professional attraction contributes to entrepreneurial intention[10–12], also found significant relationship between professional attraction and entrepreneurial intention by using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:H1: Professional attraction has a positive direct effect on entrepreneurial intention

2.2. Professional Attraction and Entrepreneurial Experience

- Based on[13], entrepreneurs can be created by their experience as they grow and learn, being influenced by teachers, parents, mentors and role models throughout their growth process, in which, the students foresee their future career as owning their business, are, on average, more prone to risk, show higher levels of creativity and familiarity with entrepreneurship issues[14]. Hence, as in effectiveentrepreneurship, male, older, and more professionally experienced students tend to reveal (other things remaining constant) higher entrepreneurial intents[14]. Therefore, another hypothesis can be put forward:H2: Professional attraction has a positive direct effect on entrepreneurial experience.

2.3. Entrepreneurial Capacity and Entrepreneurial Experience

- Entrepreneurial capacity focuses on student’s aptitude to start any entrepreneurial project or a firm.[15] found that for local students, the perceived feasibility (entrepreneurial capacity) of becoming entrepreneurs is strongly associated to the graduate education experience. However, it did not affect the level of entrepreneurship positively, for the assumption that their capacity is not enough to take the risk of doing business[15]. Thus, it is postulated that:H3: Entrepreneurial capacity has a positive direct effect on entrepreneurial experience

2.4. Entrepreneurial Capacity and Entrepreneurial Intention

- According to[10], entrepreneurial capacity is significant at conventional level and has positive relationship withentrepreneurial intention. Based on[12] in Taiwan entrepreneurial intention would be more closely related to entrepreneurial self-capacity, and study has found that entrepreneurial self-efficacy (capacity) has positive relationship with the intention to entrepreneurial[12]. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:H4: Entrepreneurial capacity has a positive direct effect on entrepreneurial intention

2.5. Entrepreneurial Experience and Entrepreneurial Intention

- Reference[16] defines entrepreneurial experience as the quantity and quality prior exposure to entrepreneurship that refers to personal experience in a family business, family involvement in a business or participation in a start-up. Past researcher investigating the relationship betweenentrepreneurial experience and entrepreneurial intention then found significant relationship in university student[17],[18]. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:H5: Entrepreneurial experience has a positive direct effect on entrepreneurial intention

3. Methodology

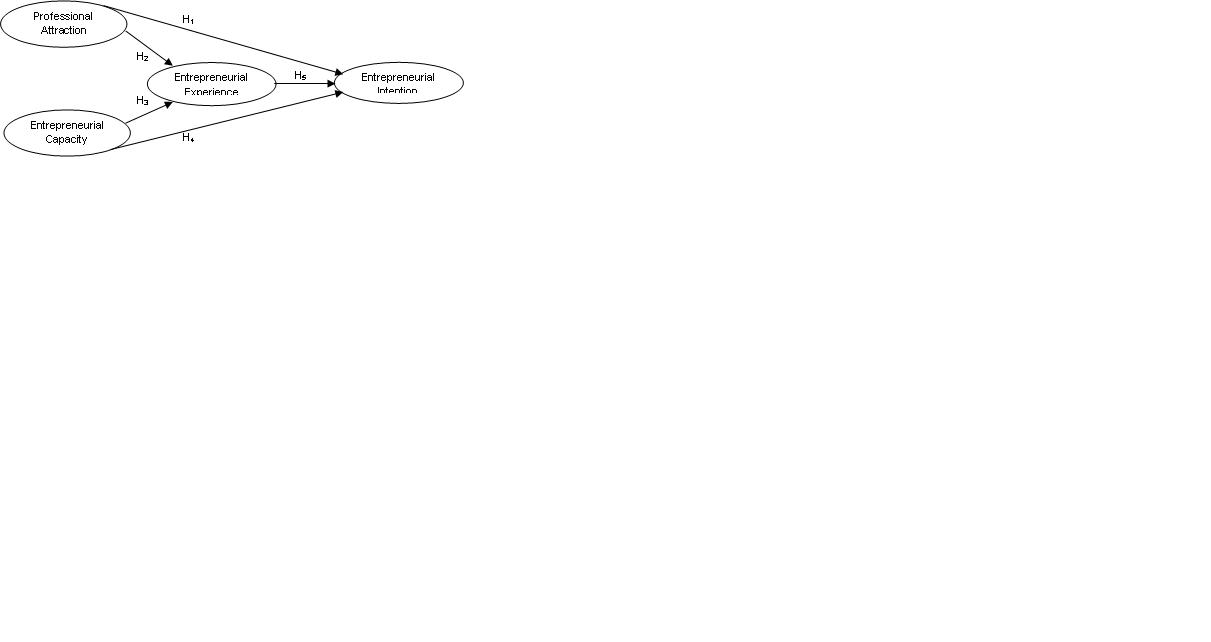

- This study has been formulated based on Theory of Planned Behaviour[5], and the variables under investigation in this study are shown in Fig. 1.

| Figure 1. Research Framework |

3.1. Sampling and Instrument

- Based on random sampling method, a total of 200 who enrolled in technical courses of a university in the South of Malaysia were selected to be the respondents in this study and the participation were confirmed by their response to the structured questionnaires that contained measures of the constructs of concern. The questionnaires were responded by 129 respondents, which contributed to 64.5 % of response rate. The first section of the questionnaire consisted of the demography of the respondent, such as race and gender, which each of them applied nominal scale. While the second section measured the variables used in this study. The questionnaire was adopted from Entrepreneurial Intention Questionnaire (EIQ) by[12] for three variables which are professional attraction, entrepreneurial capacity, and entrepreneurial intention. The instrument from EIQ has been checked and tested by previous scholars[4],[19–22]. Each variable was measured using previously developedinstrument as follows: professional attraction-6 items; entrepreneurial capacity-5 items; and entrepreneurial intention-6 items, all adopted from EIQ by[12] and entrepreneurial experience-3 items was adopted from[23]. All measures used 5-point interval scale of (1) total disagreement to (5) total agreement.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Analysis

- A total of 129 respondents completed the questionnaires, of which 46 (35.7%) were males and 83 (64.3%) were females. In terms of race, the sample consisted of Malays (55%), Chinese (38%), as well as Indians (7%).

4.2. Testing of Hypothesized Model

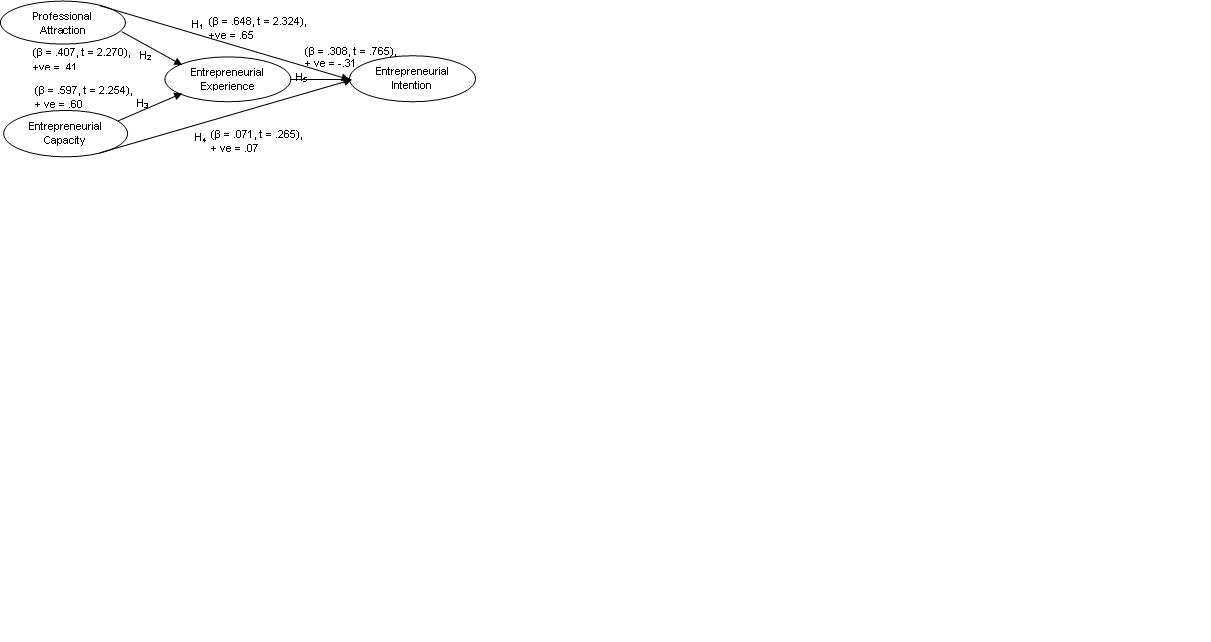

- The result indicates that the Cronbach’s Alpha for the 20 items is between the ranges of 0.763 to 0.806, showing the consistency reliability of the measure used in this study are considerably high. To test the hypotheses, the revised model was assessed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The results, shown in Figure 2, indicate only three significant direct effects in the revised model. The overall model fit statistics show that the model fits the data well, with χ2 = 33.734 (p = 0.249); GFI = 0.915; CFI = 0.990; RMSEA = 0.036 and ratio (cmin/df) =1.163. As shown in Fig. 2, three hypothesis (H1, H2, H3) are supported, while the remaining two (H4 and H5) are rejected. In H1, professional attraction had significant direct effect on entrepreneurial intention (β = .648, t = 2.324). H2 was also supported since the effect of professional attraction on entrepreneurial experience was positive and significant (β = .407, t = 2.270), as well as H3 where entrepreneurial capacity was found to be positively related to entrepreneurial experience (β = .597 t = 2.254). Nevertheless, H4 and H5 were rejected since entrepreneurial capacity was found to be positive but not significantly related to entrepreneurial intention (β = .071, t = .265), and entrepreneurial experience had no significant direct effect on entrepreneurial intention (β = .308, t = .765). The structural model explains 93.1% variance in entrepreneurial intention.

| Figure 2. Revised Model |

5. Discussion

- The purpose of this study is to determine the relationships between professional attraction, entrepreneurial capacity and entrepreneurial experience, toward entrepreneurial intention among the technical students. Basically, the results from hypothesis testing showed that three out of five hypotheses (H1, H2, H3) were supported, while the remaining two (H4 and H5) were rejected. Therefore, the study produced interesting outcomes that the technical students: a) showed high intention in becoming entrepreneurs, b) were attracted to choose entrepreneur as their profession in the future career plan, c) had lacked of skill, knowledge and ability to start and run entrepreneurial projects, d) were aware of the skills and attitude needed to start business, e) entrepreneurial experience as a moderator variable did not affect both independent variables. Thus, this study supported the study done by[2] that background of non-economic and business education significantly influenced the intentions to be an entrepreneur in the future, despite of being weak in the entrepreneurial orientation[24]. However, it contradicted with previous study done by[25] who tested entrepreneurial experience as their moderator and yield positive relationship. The result was supported by[26] in his study on entrepreneurship education and Polytechnic students’ entrepreneurial tendencies, the uneasiness of students to become entrepreneurs could partly be attributed to the syllabus in used which was not effective in imparting entrepreneurial knowledge, skills and attributes. Since students’ attitude towards entrepreneurship can be enhanced through education[27],[28], it can be said that undergoing entrepreneurship courses (which included in business students' curriculum) may increase the students' intention towards entrepreneurship.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to express my infinite gratitude for the work done by my group members; Rabiatul Adawiyah, Fitriah Sanita, and Juzaimi Nasuredin, who are responsible for most of the research and analysis that went into this article; thank you to our family and friends for sharing the hard time and being always supportive and understanding. My deep respect and gratitude to Prof. Dr. Nik Kamariah for the assistance and guidance through out the journey. My special thanks to Rumaizah Ruslan and Md. Fauzi bin Ahmad@Mohamad, for your invaluable help. Also, my sincere appreciation to Othman Yeop Abdullah Graduate School of Business (OYAGSB), Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM), Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia (UTHM), and the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) for the opportunity given.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML