-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Diabetes Research

p-ISSN: 2163-1638 e-ISSN: 2163-1646

2019; 8(3): 41-47

doi:10.5923/j.diabetes.20190803.01

Health Information Technological State of Diabetes Management: Southwestern Nigeria as a Case Study

Ayanlade O. S.1, Oyebisi T. O.1, Kolawole B. A.2

1African Institute for Science Policy and Innovation (AISPI), Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

2Department of Medicine, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ayanlade O. S., African Institute for Science Policy and Innovation (AISPI), Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Due to the vast benefits of Health Information Technology in managing chronic diseases like diabetes, this study therefore seeks to identify the Health Information tools used for diabetes mellitus management in Southwestern Nigeria, and also assesses the level of adoption of the tools for optimal management of diabetes in selected hospitals. This study was carried out in Southwestern zone of Nigeria. For the purpose of this study, six hospitals were selected purposively from all the six states of the selected zone, so that each state was represented in the study. Therefore, the six hospitals, which were three federal and three state hospitals, were strategically selected from the states. Some health stakeholders, the Nurses, Doctors (from senior registrar level to consultants), Pharmacists, Medical record officers, ICT unit professionals and Laboratory Scientists (in care of patients’ blood tests, urine tests, x-ray and so on) roles were involved in the study. Altogether, three hundred and thirty six (336) respondents were selected for the survey, chosen across all the six states, distributed as 156 Patients, 24 Nurses, 24 Doctors, 36 Pharmacists, 36 ICT Unit professionals, 24 Medical record officers and 36 Laboratory Scientists. However, there was a response rate of 89.3%, meaning that 336 copies of questionnaire were distributed, while 300 copies were retrieved. Primary data were used to collect the data for the study. The Primary data were in the forms of questionnaire and observation. Of all the twelve Health Information tools considered, it was noted that Digital monitoring devices are the most common tool, as it is owned by hospitals, it is also owned by many of the patients. Therefore, most of the staff and patients selected Digital monitoring devices as an important tool useful for diabetes management.

Keywords: ICT, Diabetes management, Chronic diseases

Cite this paper: Ayanlade O. S., Oyebisi T. O., Kolawole B. A., Health Information Technological State of Diabetes Management: Southwestern Nigeria as a Case Study, International Journal of Diabetes Research, Vol. 8 No. 3, 2019, pp. 41-47. doi: 10.5923/j.diabetes.20190803.01.

1. Introduction

- The population of chronic diseases is increasing rapidly in recent times, together with the costs of the disease management, and the complications associated with the disease (Zarkogianni et al. 2015). This is obvious in the alarming rate of chronic diseases in Nigeria, Africa and even globally (Papatheodorou et al. 2016). For example according to International Diabetes Federation, It is estimated that more than 415 million people are suffering globally from diabetes mellitus, simply called diabetes, and the number will reach 642 million at the end of 2040, with associated deaths of 4.9 million, and an annual cost of USD 612 billion (Atlas & Edition 2015). Similarly in Sub-Saharan Africa, diabetes rate is expected to rise from 4% in the year 2010 to around 6% in 2035, which is about doubling the number of people living with diabetes in the area (Shaw et al. 2010, Guariguata et al. 2014). Most importantly in Nigeria as at 2012, Brodie (2012) noted that more than 6 million people are living with diabetes in Nigeria, and the population will increase with more complications, if proper way of managing it is not in place (Brodie 2012). Diabetes is a chronic disease characterized by increase in blood glucose levels as a result of defects in the secretion of insulin, insulin action or the combination of the two (Zarkogianni et al. 2015). Some of the complications of diabetes, among others, include neuropathy, cardiovascular diseases, nephropathy and retinopathy. There are different systems or ways of managing chronic diseases in the health sector, for example using paper system and/or using Health Information Technology, HIT. However, Health Information Technology, a subset of the broad umbrella of Information and Communications Technology, ICT, has been proven effective in the diagnosis and management of chronic diseases like diabetes, as proven by many researchers (such as (Lamprinos et al. 2016, Ayanlade et al. 2018, Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. 2018, Islam et al. 2019), as they require life care plan. Paper medical record system has so many disadvantages when it comes to diabetes management. For example, the damage the scattering medical records of patients do to diabetes management cannot be over emphasized.On the other hand, Health Information Technology () is believed to improve healthcare quality, while decreasing costs. Thus, health care experts, policy makers and consumers consider to be critical in transforming the health care industry (Wager et al. 2017, Ayanlade et al. 2019). This transformation is as a result of (such as Electronic Medical Records, Clinical Decision Support Systems, Computerised Physician Order Entry), Computerised prescription, test ordering and so on) enhancing the safety, quality, and patient-centeredness of care, while helping to contain costs. This is due to the fact that it provides knowledge about guidelines and safety, information about patient conditions; treatments and other pertinent characteristics; and reminders to physicians at the point-of-care (Pinsonneault et al. 2017). This is necessary among others, because diabetes as a self- managing disease, requires appropriate technology to empower patients, so as the patients to take responsibilities of monitoring and management of their health, and the healthcare providers also by providing both motivational and educational support to the concerned patients (Glasgow et al. 2012, Hunt 2015). Some of the examples of Health Information Technology tools used for diabetes management include Mobile Health Technology; Internet/cloud-based technology; Electronic Medical Record System (EMRS), involving for example, electronic booking and referral; Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS); Computerised Physician Order Entry; Electronic/computerized prescription; Electronic Test Ordering; Electronic mail, e-mail; Updated Organizational websites; Digital monitoring devices and so on.Due to the ubiquity of mobile phones worldwide, the availability, popularity and the range of features in mobile phones, coupled with the fact that about three quarter of the world’s total population have access to mobile phones (Bank 2012), mobile phones have been in use for diabetes management, thus for educational support through text-messaging and therefore increases access to needed information for people with diabetes (Hunt 2015). Also, mobile phones enhance health data collection, communication, education and patient monitoring (Organization 2011). Also, the strong attachment people have for mobile phones in carrying them all about also opens up for real time messaging and opportunities for continuous symptom monitoring, while also constantly connecting to health practitioners outside medical visits (Hamine et al. 2015). For instance, with the help of mobile phones, health practitioners could set reminders, and have interactive monitoring of patients, so as to schedule visits for high-risk patients, and for treatment adjustments (Kiselev et al. 2012, Ayanlade et al. 2018).Likewise, due to a constraint in available time to both patients and health practitioners, internet/web and/or cloud-based monitoring and education is beneficial, and can be used to complement patients’ visit to their healthcare providers (Avdal et al. 2011). The web/cloud technologies are necessary because most of the time, patients are not followed up until their next appointment with their health practitioners, which are even usually short in duration. Whereas, patients need advice on for example, how to manage their glucose levels and so on, which usually transpire between medical visits (Hsu et al. 2016).Tieu et al. (2015) noted that for a patient with chronic diseases, like diabetes, to have qualitative healthcare, there have to be Electronic Medical Record System, EMRS (Cebul et al. 2011, Reed et al. 2012); evidence-based guidelines (O'Connor et al. 2011); self blood glucose monitoring and monitoring of other necessary medications (Group 2010); and educating and empowering patients (Battersby et al. 2010, Goldzweig et al. 2013). Along this line, Electronic Medical Record System can be defined as a secure collection of personal health information of patients. If it is web-based, it is regarded as Patient Portal, and if not, regarded as Electronic Medical Record System (Tieu et al. 2017). Electronic Medical Record System/Patient Portal as the case may be, facilitates a consistent individual medical care by allowing continuous monitoring and evaluation of the concerned patient, for example through generation of periodical (monthly, quarterly and so on) reports; thus it is a tool for clinical management (Allain et al. 2017). Therefore, EMRS has various health information features depending on the organization and its needs such as discharge summaries, recent doctor visits, laboratory results and so on. Some electronic medical record system can even allow patients to request prescription refills, securely message their doctors, schedule non-urgent appointments and so on (Ayanlade 2018, Bush et al. 2018). Thus, EMRS has become the centre of workflow because it has been a way for patients to self-manage their chronic diseases by promoting their knowledge and awareness, self-efficiency and improved health behaviours and communication (Urowitz et al. 2012, Osborn et al. 2013, Dhanireddy et al. 2014), while also helpful in controlling the risk factors of chronic diseases (Woods et al. 2013). However, the most important aspects of EMR include electronic booking, electronic referral and electronic prescription. Although electronic booking, which is essentially to make appointments with health practitioner (Chambers & Wakley 2016), also facilitates easy and fast access to health practitioners, by allowing them to have a manageable size of patients, which they will be able to attend to very well. This also allows the clinicians to spend considerable time with their patients (Pillay & Aldous 2016).Furthermore, Electronic Medical Record System, EMRS could also incorporate some tools that can assist the clinicians to decide on the course of action or treatment plans for patients, the tools are called Clinical Decision Support System, CDSS, according to Ayanlade et al. (2018) and Anchala et al. (2015). This incorporation, such as prompts when screening for complication is needed, has proven to avoid or reduce treatment errors, in that it influences the decisions of Clinicians, thus improving the quality of treatment given to patients (Miller et al. 2015). According to Basch et al. (2018), this might be because sometimes, if there is no reminder or prompting, healthcare providers and patients may fail to perform some required tasks (such as authorization or completion of laboratory tests). In like manner, Panattoni et al. (2018) stated that CDSS-incorporated Electronic Medical Record System also serves as reminder for patients about preventive care. Moreover, Ranji et al. (2014) also noted that Clinical Decision Support System could also be combined with Physician order entry or computerized physician order entry to reduce medication errors. For instance, by making sure that the criteria for ordering medications are met such as the required dose, absence of contra-indications, allergies or drug interactions and so on. Moreso, since patient portals are web-based, that makes patient health information available, while also linking patient electronic medical record to various care providers (Chewning et al. 2012, Irizarry et al. 2015). Thus, this linkage allows electronic referral to be possible and easier, without any stress of moving health information around healthcare organizations.Furthermore, electronic communications, particularly electronic mail (e-mail) has supplemented face-to-face consultations with clinicians, especially among patients with chronic diseases (Ye et al. 2010). This is because it fosters communications needed when patients need counseling, instead of frequent physical visits to the health practitioner (Huxley et al. 2015), thus enhancing patient satisfaction and healthcare quality. Some researchers (such as (Morgan 2015)) reported that sometimes, email is incorporated in patient portal, to engage the patient and to allow direct and intensive communication with healthcare practitioners. For example, Zainudin et al. (2018) reported that feedback on medication could be reviewed by health practitioners through email, and necessary advise be given on medication adjustment to avoid diabetes complications.Also, the use of several digital devices for health monitoring like glucometer, has enhanced the management of chronic diseases like diabetes, and these are called ‘consumer technologies’. This is necessary to engage patients to improve healthcare provider workflow (Kumar et al. 2016).Therefore, due to the vast benefits of Health Information Technology in managing chronic diseases, especially diabetes, this study thus seeks to identify the Health Information tools used for diabetes mellitus management in Southwestern Nigeria, and also assesses the level of adoption of the tools for optimal management of diabetes in selected hospitals in Southwestern Nigeria.

2. Materials and Methods

- This study was carried out in Southwestern Nigeria. Nigeria has six geopolitical zones, out of which southwest is one. The other geopolitical zones in Nigeria are Northeastern, Southeastern, Northcentral, Northwestern and Southsouth. This zone (southwestern) has six states, which are Ondo, Osun, Ogun, Lagos, Ekiti and Oyo States. For the purpose of this study, six hospitals were selected purposively from all the six states of the selected zone, so that each state was represented in the study. Therefore, the six hospitals, which were three federal and three state, were strategically selected from the states.Some health stakeholders, the Nurses, Doctors (from senior registrar level to consultants), Pharmacists, Medical record officers, ICT unit professionals and Laboratory Scientists ( in care of patients’ blood tests, urine tests, x-ray and so on) roles were involved in the study. Altogether, there were three hundred and thirty six (336) participants selected for the survey, chosen across all the six states, distributed as 156 Patients, 24 Nurses, 24 Doctors, 36 Pharmacists, 36 ICT Unit professionals, 24 Medical record officers and 36 Laboratory Scientists. However, there was a response rate of 89.3%, meaning that although 336 copies of questionnaire were distributed, only 300 copies were retrieved. The relatively small number of respondents for this study was as a result of as it were in a clinic, and not in the totality of hospital. Also, the respondents were randomly chosen in a case that the number available is more than the number needed. For instance when the number of available patients is more than 156 needed, random sampling was used to select the needed number of patients.Primary data were used to collect the data for the study. The Primary data were in the forms of questionnaire and observation. Observation technique was used to validate the filled contents of questionnaire. It was carried out using a standard checklist to confirm the health information technology options or tools in the diabetes clinic of the selected hospitals, using a field note. A field note was used so as to have a consistent list for the survey, used across all the hospitals. There are various and numerous Health Information Technology tools that can be used to manage chronic diseases like diabetes. However, for the purpose of this study, twelve (12) health information technology tools were presented, the tools were gathered from the literature, following a rigorous research to benchmark and compare the health information technologies in use in the developed and developing countries, the generated technologies thus formed the presented technologies. The presented technologies, as also discussed earlier are Electronic Medical Record System, EMRS; Electronic booking; Electronic referral; Electronic Test Ordering; Electronic Test Results; Electronic Prescription; Electronic mail, email; Clinical Decision Support System, CDSS; Mobile technology; Organizational websites; Internet educational services; and digital monitoring devices. The respondents were allowed to select as many tools as in use in their respective hospitals.

3. Results and Discussion

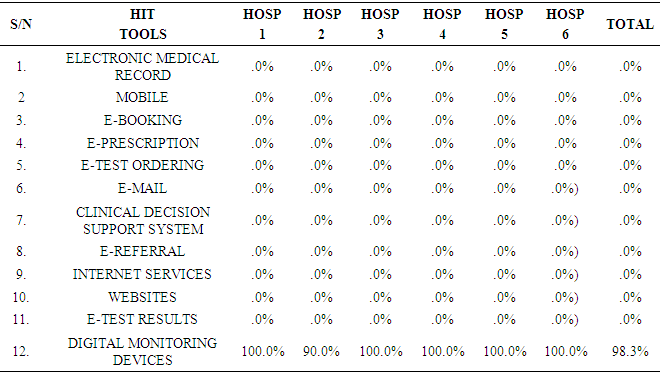

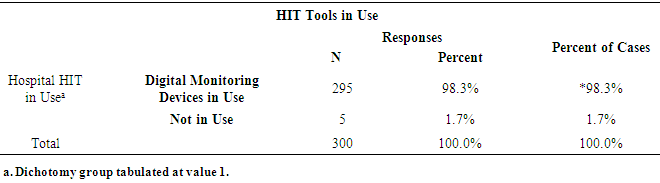

- The responses of the participants were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Scientists, SPSS, version 20.0. Multiple response analysis was carried out to evaluate as many tools as selected by the respondents. The frequencies of all considered Health Information Technology tools, HIT are presented in Table 1. Of all the twelve Health Information tools considered, it was noted that Digital monitoring devices are the most common tool, as it is owned by hospitals, it is also owned by many of the patients as illustrated in Table 2. Therefore, most of the staff and patients selected Digital monitoring devices as an important tool useful for diabetes management as also obvious in the multiple response analysis in Table 2. This might be because the device is used to empower patients as Kaufman et al. (2016) noted that as diabetes is a self-managing disease, patients have to possess these devices so that they could monitor their health, for instance, their glucose levels. The digital monitoring devices could be in the forms of glucometer (to measure blood glucose), digital blood pressure cuff, digital weighing scale and so on.

|

|

|

|

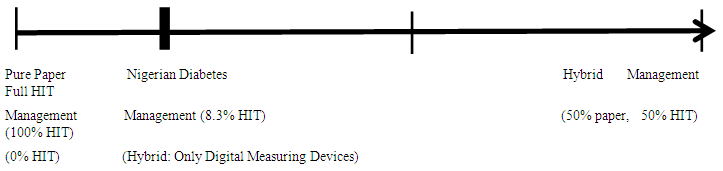

| Figure 1. Status of Nigerian Health Sector in Diabetes Management |

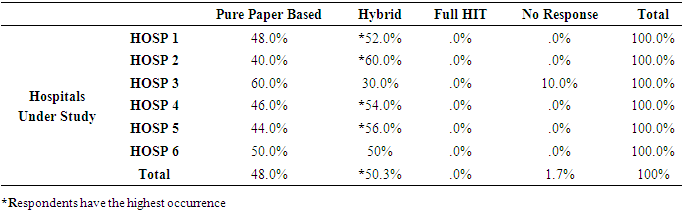

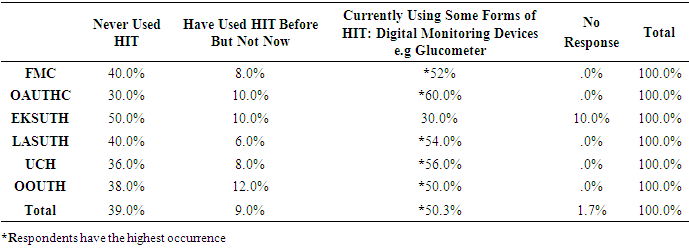

of HIT (expressed in percentage) is in use to manage diabetes in Nigeria, which is calculated as 8.3% of HIT.Some other respondents in the hospitals (as already discussed in Table 4), agreed they have never used HIT before, while very few were still of the opinion that they have used HIT before, but not in use again. This minority opinion, according to Idowu et al. (2008), might be explained that since the inception of ICT, many hospitals have tried to implement HIT, but the implementation was not sustained and maintained, maybe because of some factors that hindered the users’ acceptability of the technologies (Ayanlade et al. 2019).

of HIT (expressed in percentage) is in use to manage diabetes in Nigeria, which is calculated as 8.3% of HIT.Some other respondents in the hospitals (as already discussed in Table 4), agreed they have never used HIT before, while very few were still of the opinion that they have used HIT before, but not in use again. This minority opinion, according to Idowu et al. (2008), might be explained that since the inception of ICT, many hospitals have tried to implement HIT, but the implementation was not sustained and maintained, maybe because of some factors that hindered the users’ acceptability of the technologies (Ayanlade et al. 2019). 4. Conclusions

- Of all the twelve Health Information tools considered, it was noted that digital monitoring devices are the most common tool, as it is owned by hospitals, it is also owned by many of the patients. Therefore, most of the staff and patients selected Digital monitoring devices as an important tool useful for diabetes management. Moreover, the status of Nigerian diabetes management was assessed from the respondents’ point of view and the study concluded that the hospitals are presently using some forms of HIT, that is hybrid system, as established also in the previous results of HIT tools in use, using digital monitoring devices. However, the hybrid management chosen by the respondents, and the respondents agreeing to be using some forms of HIT might be credited to the use of digital monitoring devices being in use for the patients in all the hospitals studied.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML