-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Diabetes Research

p-ISSN: 2163-1638 e-ISSN: 2163-1646

2019; 8(1): 4-8

doi:10.5923/j.diabetes.20190801.02

Knowledge of Risk Factors and Complications of Diabetes in the Indian Ethnic Population of Malaysia Undiagnosed to Have Diabetes

Sheikh Salahuddin Ahmed1, Tarafdar Runa Laila2, Pavadai Thamilselvam3, Kishantini Subramaniam4

1Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Defense Health, National Defense University of Malaysia (NDUM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine and Defense Health, NDUM, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

4Final Year MD Student, Faculty of Medicine and Defense Health, NDUM, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Sheikh Salahuddin Ahmed, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Defense Health, National Defense University of Malaysia (NDUM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: The prevalence of diabetes mellitus along with its dreaded complications is increasing worldwide. The awareness of knowledge of diabetes in the community is important, so that steps can be taken to prevent it and its complications. Objective: The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge of risk factors and complications of diabetes among peoples of Indian ethnic origin in Malaysia who were not known to have diabetes. Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out among adult people (≥18 years) attending for health check-up in a community service centre at Cheras which is one of the district of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Data was collected using a predesigned semi-structured questionnaire with face-to-face interview after taking informed written consent from 76 respondents. Results: The mean percentage of correct response on risk factors and complications were 73.2%, and 74.4% respectively. Median age of the participants was 47.5 years (SD 1.4); the majority of the participants were females (69.7%) and the median body mass index was 26.6 (SD 5.5). Conclusion: This study indicates that the non-diabetic Indian population residing in urban area of Malaysia displayed satisfactory knowledge regarding the risk factors and complications of diabetes.

Keywords: Diabetes, Indian ethnic, Malaysia, Cheras, Knowledge, Awareness, Risk factors, Complications

Cite this paper: Sheikh Salahuddin Ahmed, Tarafdar Runa Laila, Pavadai Thamilselvam, Kishantini Subramaniam, Knowledge of Risk Factors and Complications of Diabetes in the Indian Ethnic Population of Malaysia Undiagnosed to Have Diabetes, International Journal of Diabetes Research, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 4-8. doi: 10.5923/j.diabetes.20190801.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Diabetes mellitus is a clinical condition characterized by chronic hyperglycaemia resulting from inadequate insulin secretion or insulin action associated with impaired carbohydrate, lipid and protein metabolism. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most common form, which accounts for 90% to 95% of all diabetic patients [1]. The prevalence of T2D continues to grow with increase in the burden to the health care providers of most of the countries of the world [2]. A wide variety of risk factors are known to cause T2D; these include overweight or obesity, sedentary lifestyle, physical inactivity, hypertension, family history of diabetes, pregnancy, polycystic ovarian disease, smoking and alcohol consumption [3-6]. Studies have shown that excess drinking of sugar sweetened beverage or increased intake of a low-fiber diet with a high glycemic index, is positively associated with a higher risk of T2D [7,8]. High saturated fatty acid intake is associated with an increased risk of T2D independent of other risk factors [9]. Studies have also found that sleep deprivation is another risk factor for T2D [10]. The rising trend of T2D is also due to factors like aging population and urbanization.The complications of T2D constitute a major worldwide public health problem with increased morbidity and mortality. T2D patients are more susceptible to different forms of acute (e.g., hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state) and chronic complications (vascular and nonvascular). The macrovascular complications (ischemic heart disease, strokes, and peripheral arterial disease) and the microvascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) are well recognized. Peripheral arterial disease and neuropathy are responsible for diabetic foot disease that may lead to amputation. The examples of nonvascular complication include fatty liver, cataract, diabetic dermopathy and certain cancers. Epidemiologic evidence has demonstrated that diabetes may increase the risk of colorectal, liver, bladder, breast and kidney cancer [11-15]. T2D is often silent, and people may present with one of its life-threatening complications. The disease is now preventable by avoiding the risk factors known to cause diabetes. Increased level of public awareness that include knowledge of diabetes, attitude and practice of healthy life style is vital. Appropriate life style modifications and correction of modifiable risk factors are of paramount importance to prevent diabetes. Knowledge is also essential for adequate management of diabetes and diabetes related complications.

2. Aim of the Study

- The aim of this study was to assess the level of knowledge of risk factors and complications of diabetes mellitus among the adult people of Indian ethnic origin who were not known to be suffering from diabetes and who were living in one of the urban area of Malaysia.

3. Methodology

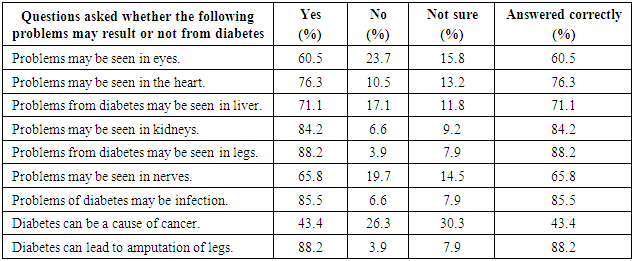

- It was a cross sectional study and the data was collected from the local Indian volunteers attending a community service arranged at a district town of Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The community service was free health related check-up which was provided by volunteer health care personals and senior medical students of different universities of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The participants were asked to report in the morning with overnight fasting for about 8—10 hours. They went a physical medical check-up with measurement of capillary fasting blood glucose (FBG) by finger-prick test using glucometer. Inclusion criteria of this study were (a) volunteers willing to participate in the study (b) age ≥18 years (c) male/female gender and (d) Malaysian Indians; exclusion criteria were (a) persons known to have diabetes (b) pregnant females (c) persons having mental/ cognitive disorders (d) foreigners or non-Malaysian citizens and (e) those who had symptoms of diabetes. Due to time and resources constraint, a sample size of 110 was enrolled in the study. Out of 110 respondents, 34 subjects were excluded (20 Indians were known to have diabetes, 3 were Malays, 1 Chinese and 10 data collection forms were found incomplete), thus remaining 76 respondents fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were the total number of subjects in this study.For this study, a predesigned, semi-structured questionnaire was prepared to collect data by face to face interview. The data collection form included socio demographic information, questions regarding risk factors and complications of diabetes, measurements of body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP) and capillary FBG. Classification of BMI into underweight, normal, pre-obese, obese was based on Malaysian guidelines [16]. There were 9 questions regarding knowledge of risk factors and 9 questions for complications of diabetes (questions are shown in tables); the only question regarding attitude was whether diabetes is preventable or not. The questions were constructed in a simple way and easy to understand, so that every question could be answered. Each questions on risk factors and complications of diabetes consisted of three options which were “yes”, “no”, and “not sure”. Informed written consents were obtained from all the individuals who participated in the study. The respondents were informed that the confidentiality of the participants will be maintained. The information that were collected in the semi-structured data collection form were analysed in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version -16. Only fully completed data collection forms were included for analysis.

4. Results

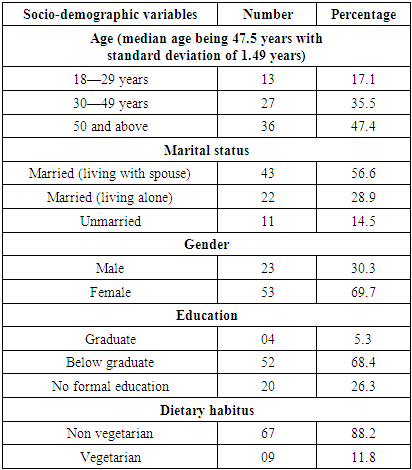

- Table 1 illustrates the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants. The age of the subjects of the study population ranged from 18 to 71 years and median age was 47.5 years with standard deviation (SD) of 1.49. Most of the respondents who participated in this study belonged to the age group ≥50 years and were married (85.5%). The male participants were 30.3% and the female participants were 69.7%. Graduate participants were 5.3%, participants having no formal education were 26.3% and the rest were 68.4% (i.e., below graduation). Dietary pattern was found to be non-vegetarian in 88.2% of the participants.

|

|

|

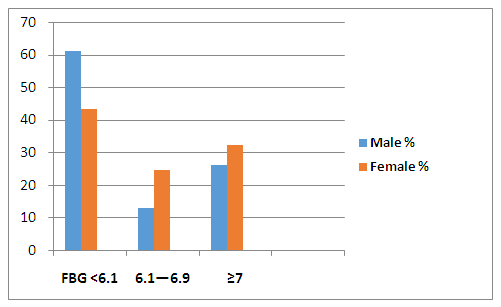

| Figure 1. Bar diagram showing the distributions of capillary fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels (in mmol/L) detected using glucometer among male and female subjects not known to have diabetes (n=76) |

|

|

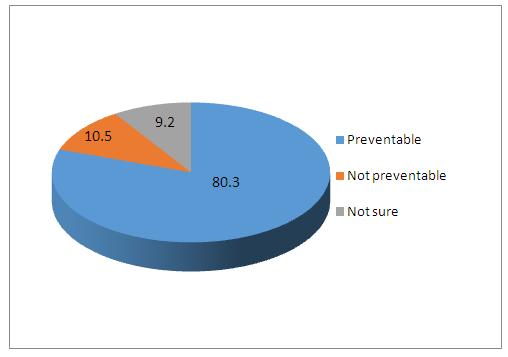

| Figure 2. Percentage of response to a question whether diabetes is preventable or not (n=76) |

5. Discussion

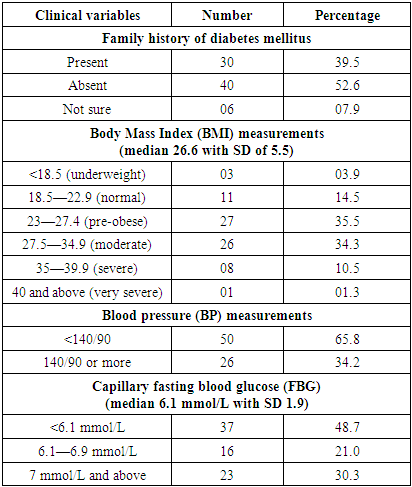

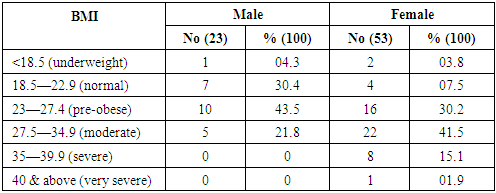

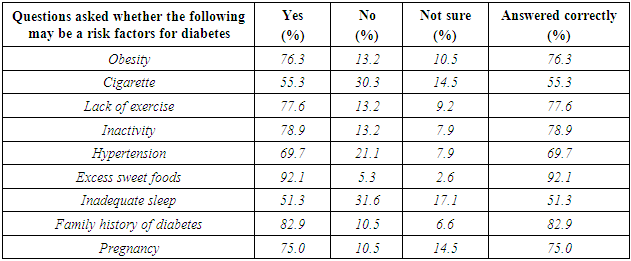

- The findings in this study indicate that the non-diabetic Indian ethnic people of Malaysia displayed satisfactory knowledge regarding the risk factors and complications of diabetes. The average value of correct response regarding knowledge of risk factors and complications of diabetes was 73.2% and 73.9% respectively. Excessive sweet foods, family history and inactivity were found to be highest correct answers among the risk factors; cigarette smoking was the lowest correct answer. Diabetes can lead to amputation of leg, infection and kidney disease were found to be highest correct answers among the risk factors; however, majority of respondents failed to identify that cancer is also a complication of diabetes. Majority of the study subjects (80.3%) were aware of that diabetes is a preventable disease.A study conducted on general population of Kuala Lumpur also revealed that the level of diabetes knowledge among the respondents were reasonably good [17]. They compared the level of knowledge among Malay, Chinese and Indian ethnicity and found the level of knowledge good with average scores of 50%, 55% and 56.6% respectively. A study revealed that the level of knowledge regarding diabetes was poor among the indigenous (Orang Asli) people in Peninsular Malaysia [18]. The majority of respondents failed to identify correct options such as obesity, lack of exercise, hereditary condition and increase age as a cause of diabetes. The poor knowledge of diabetes in the indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia may be due to their remote settlement with lack of accessibility to the city. In our study, the respondents were living in the urban area. In this study, 39.5% of the participants had family history of diabetes and 46.1% were found obese (BMI ≥27.5) as per Malaysian Guidelines [16]. Females were found to have increased prevalence of obesity as compared to male (58.5% versus 21.8%). BP was found to be ≥140/90 mmHg in 34.2% of all the study subjects. Capillary FBG measured by glucometer revealed a level of ≥7 mmol/L in 30.3% of all subjects. 32.1% of female and 26% of male had a capillary FBG ≥7.0 mmol/L. These findings indicate that a substantial group of people of this study were unaware of their condition and are at a high risk of diabetes and hypertension; they need further evaluation by appropriate health care professionals as well as practice of effective healthy life style. For the diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes the most common measurement is based on venous plasma glucose. The relationship between venous plasma and capillary whole blood measurements is not fixed but is dependent on sampling time [19]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), under fasting conditions, plasma venous glucose values are about 10% higher than capillary blood values [20]. Malaysian guidelines recommend screening for diabetes and prediabetes by measuring venous plasma glucose whenever capillary FBG measured by glucometer is >5.6 mmol/L in an asymptomatic individual [21]. T2D is often silent and undiagnosed which varies widely; a review of data from seven countries found that between 24% and 62% of people with diabetes were undiagnosed, unaware and untreated [22]. It has been reported that up to 25% of newly diagnosed patients with T2DM already have microvascular complications, and there is a 6 to 7-year time lag between the onset and the diagnosis of T2DM [23]. T2D is preventable by adopting a healthy diet and increasing physical activity.

6. Limitations of the Study

- There are some limitations of this study. The findings of this study may not reflect the actual knowledge on diabetes among the entire ethnic Indian population of Malaysia living in urban area. The study was conducted in a small sample size; and the data was derived from only one part of Kuala Lumpur.

7. Conclusions

- The majority of people of Indian ethnicity, residing in urban area of Malaysia are aware about the risk factors and complications of diabetes; therefore, they have demonstrated adequate knowledge. They have also responded by selecting that diabetes mellitus is a preventable disease. Knowledge about diabetes is important factor, but merely not enough; practice of appropriate life style modifications and corrections of risk factor are of paramount importance in the prevention of diabetes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We are thankful to the Indian senior medical students of different universities of Malaysia situated in Kuala Lumpur who interviewed the participants and filled up the data collection forms. We are also thankful to the organizers of the community service to help us in conducting the study. Finally, we also extend our thanks to the participants for their active participation in providing the data for our study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML