-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Diabetes Research

p-ISSN: 2163-1638 e-ISSN: 2163-1646

2017; 6(1): 7-15

doi:10.5923/j.diabetes.20170601.02

Effect of Self-learning Package on Quality of Life of Diabetic Patients at Mohaiel Asser Region, KSA

Fathia Attia Mohammad1, Ancy Yohannan2

1Lecture of Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing Zagazig Unevirsity, Egypt

2Lecturer of Medical Surgical Nursing, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Mohail Assir, King Khalid University, Egypt

Correspondence to: Fathia Attia Mohammad, Lecture of Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing Zagazig Unevirsity, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Back Ground: Diabetes Mellitus is one of highest challenges worldwide, represent major public health problem in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for various reason with huge impact on quality of life. Individual's physical, emotional, and social well-being, are affected. It demand necessary steps to improve the quality of life of those patients, decrease cost management, avoid related complications and improve all level of health and maintain proper daily living activities. Objective: The main aim of this study was to assess the competency of illustrated self-learning package in improving quality of diabetic patients life. Subject & Method: A quasi experimental study with one group pretest posttest design was followed. The sample consisted of 50 diabetic patient selected based on inclusion criteria. A 36-items short form health survey questionnaire was used to assess participants quality of life in the pre-posttest. A self-instructional package in the form of illustrated booklet and CD, was distributed for all participants. Result were indicates to majority of participants were female and had a hereditary family diseases with compliance to daily treatment, majority of QOL dimensions posttest were improved compared with pretest. Conclusion: Diabetes care is a lifelong responsibility, an educational self-learning illustrated package can serve as a choice method for patients with diabetes to enhance their disease-related knowledge, skills and compliance to strategies that improve QOL. There is a needs to initial QOL assessment, enhance awareness for newly diagnosed Pt. and periodically. An educational self-learning illustrated package can serve as a choice method for patients with diabetes to enhance their disease-related knowledge, skills and compliance to strategies that improve QOL.

Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Kingdome of Saudi Arabia, Quality of Life, Self learning package

Cite this paper: Fathia Attia Mohammad, Ancy Yohannan, Effect of Self-learning Package on Quality of Life of Diabetic Patients at Mohaiel Asser Region, KSA, International Journal of Diabetes Research, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2017, pp. 7-15. doi: 10.5923/j.diabetes.20170601.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

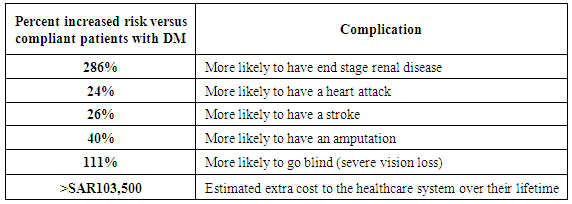

- Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major public health problem, its complications represent a significant medical, social and economic problem [1]. Many people's with diabetes have complications of DM and/or other long-term conditions. Nearly 1 in 5 people with DM have clinical depression and anxiety that increase health care related costs by around 50% [2]. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic, complex disease, require continuous medical care, with strategies of reducing the multi-factorial risks beyond the glycemic control [3]. DM considered a sixth cause of death worldwide; every 7 seconds, one person dies from DM [4]. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) reported that, at present, there are 415 million people worldwide suffering from DM, aged between 20 and 79 years old, the global prevalence being of 8.8%, and it is estimated that in 2040 their number will grow up to 642 million, with a prevalence of 10.4% [5].There is a fact that most world countries reported a permanent increase of the DM prevalence and incidence, so prevention measures are required, including optimizing the lifestyle and simultaneous control of body weight. Irreversible chronic complications in patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus leading not only to a poor life quality but also to a 2-5 times increase of costs of management, and it is necessary to tight follow-up of these patients for the rest of their lives [6]. Saudi Arabia is one of the 19 countries and territories of the IDF MENA region. 415 million people have diabetes in the world with more than 35.4 million people in the MENA Region; will rise to 72.1 million in 2040. There were 3.4 million cases of diabetes in Saudi Arabia in 2015 [7]. DM in Saudi Arabia represent 23.9% of the population compared to 23.1% in Kuwait, and 19.8%, in Qatar. The global average figure is far lower, at 8.3% [8].3 to 4 out of 18 million Saudi residents between the age of 20 to 79 years of which approximately 70% are Saudi nationals suffered from DM [9], about 3.6 million have diabetes, about 90% of them have T2D [10]. In Saudi Arabia, among Pt. with DM over the age of 30, an estimated 40.3% are unaware of their condition [8]. Furthermore, with 25.5% of Saudi population above the age of 30 displaying signs of pre-diabetes and 28.7% of the Saudi population categorized as obese and hence at risk of T2D, the number of people with T2D is expected to rise significantly [11-14]. Indeed, by 2035, the number of Pt. with DM aged between 20 and 79 years old is estimated to reach 7.5 million in Saudi Arabia [15], with the increase in economic and societal burden, it is predicted that around 15% of complication related costs, estimated to be SAR3.9 billion per year are due to sub-optimal therapy compliance and persistence [7, 15, 16].The epidemiologic transition in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has been fast that leads to remarkable increase in living standards, characterized by unhealthy dietary patterns, and decreased physical activity [17] & increase in the prevalence of T2DM, in addition to genetic predisposition of Saudi people to diabetes, and a high prevalence of consanguineous marriages [18].

|

2. Subject & Methods

2.1. Aim of the Study

- This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of self-learning package on Quality of Life of patients with diabetes mellitus.

2.2. Hypothesis

- There is a significant difference between quality of Life of patients with diabetes mellitus, pre-post administering the self-learning package.

2.3. Design

- A quasi-experimental, of one-group pretest-posttest designs was followed to conduct this study.

2.4. Subjects & Settings

- This study conducted at Mohaiel Asser hospital, community health care center at Mohaiel Asser region. A non-probability convenient sampling of 50 patients with diabetes mellitus who attend to receive treatment or follow up in the above mentioned setting with normal level of consciousness & willing to participate and didn’t participated in similar study before.

2.5. Instrument Tool

- Data were collected by using a questionnaire sheet that divided to two parts, first: covered demographic variables & the second was the SF-36 health survey to assess QOL [55]. This instrument provides state of health profiles and is one of the most widely used generic scales in the assessment of clinical results. It is applicable to both the general population and to patients with a minimum age of 14 and can be used in descriptive as well as evaluation studies. It included 8 dimensions of physical functioning, physical role restrictions, bodily pain, general health perception, energy and power, social functioning, emotional role restrictions, and mental health. Score is based on the short-form 36 (SF-36) standard measure. The 3-item question with scores of (0, 50, and 100), the 5-item question with scores of (0, 25, 50, 75, and 100), and the 6-item question with scores of (0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100) were considered, where higher scores indicate better QOL performance.

2.6. Preparatory & Implementing Phase

- Quality of life questionnaire was translated in Arabic version & revised by an expert. Review of the current and past literature related to various aspects of the problem was done using textbooks, scientific journals, and internet. A pretest was conducted, then based on the finding, an illustrated booklet was prepared & revised by specialist for clarity & reliability, it covered the required knowledge regarding definition, types, signs & symptoms, complication, management of DM. as well as meaning of QOL, its component, why DM impact on QOL and possible strategies that can be followed to improved, then distributed to all subject both hard & soft copy, an e-mail and telephone number were given to all participants for any additional explanation. After 3 months from package distribution the post test was conducted by the same pretest questionnaire sheet that takes 30 minutes to fill it.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

- The study was approved by ethical committee in college of applied medical sciences, Mohail and taken letters to mentioned setting directors to accomplish research. Patients were informed about the purpose of the study and about their right to withdraw at any time. The confidentiality of the information was secured and ensured.Statistical analysis Data coding, entry and statistical analysis were done using SPSS version 16.0. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used in the analysis of the study. Paired sample test is used for the testing of hypothesis.

3. Results

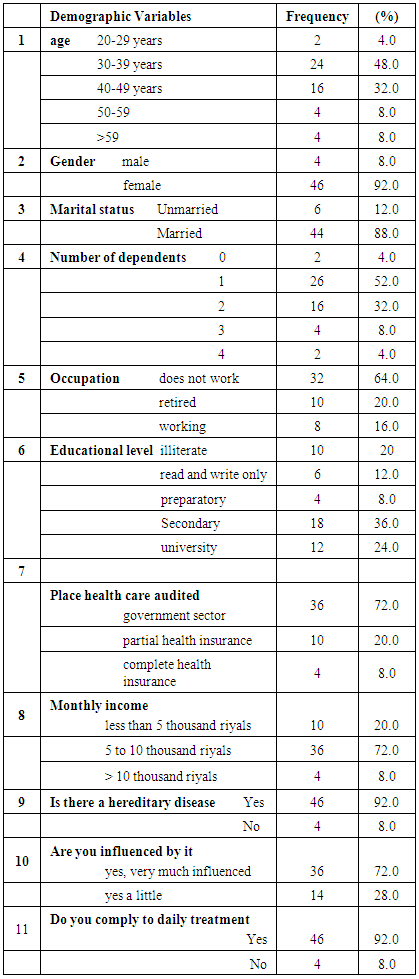

- The findings based on the descriptive and inferential statistics analysis are presented under the following headings1- Distribution of demographic variables.2- Distribution of statistical value of pretest and posttest regarding Quality of life.3- Distribution of percentage of samples in pretest and posttest under five domains.The participants were divided into four categories based on age, 1. 20-29- (4%); 2. 30-39(56%); 3. 40- 49 (32%) & 4. 50- 59 (8%). Among them 92 % were females and 8 % were males. Out of them 12 % were unmarried and 88% were married. According to the number of dependents 4 % had no dependents, 52% had one dependent, 32% had 2 dependents, 8 % had 3 dependents, 4% had 4 dependents. Nearly 2 third of subject (64%) were not working, 20% had occupation, and 92% were having hereditary disease & taking regular treatment. Regarding their level of education, 20% of participants were illiterate, 12 % were able to read and write only, 6% have preparatory school, 36% had secondary school & 24 % were university graduates. Regarding the place of healthcare audited it was found that 72% of participants were from government sector, 20% were from partial health insurance and 8 % were from complete health insurance sector. 20 % of participants were earning a monthly income less than 5000SR, 72 % were earning between 5000- 10000 SR, and 8 % had more than 10000SR income (Table 2).

|

|

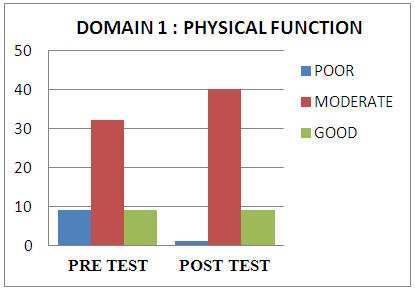

| Figure 1. Percentage distribution of participants pre-posttest physical function domain |

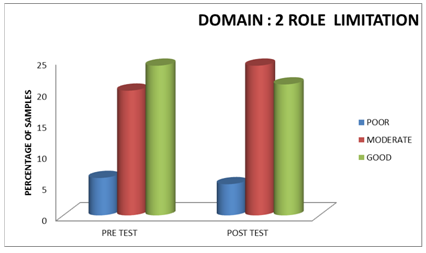

| Figure 2. Percentage distribution of subjects pre-posttest role limitation domain |

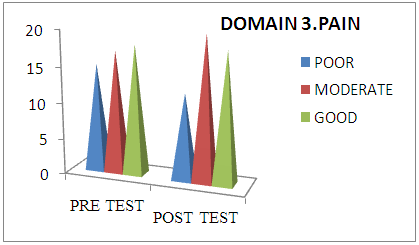

| Figure 3. Percentage distribution of subjects pre-posttest pain domain |

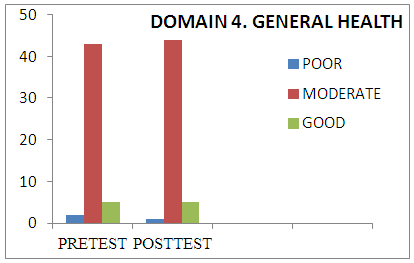

| Figure 4. Percentage distribution of subjects pre-posttest general health domain |

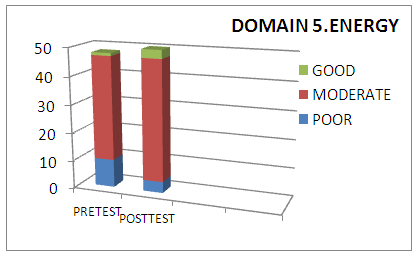

| Figure 5. Percentage distribution of subjects pre-posttest energy domain |

4. Discussion

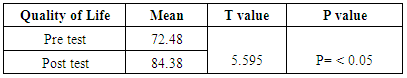

- Saudi Arabia ranks the second highest in the middle East & is a 7th highest rate in the world. Several challenges management needed, direct expense of diabetes is costing around 13.9% SR of total health expenditure that increased to 180 billion SR in year of 2014, implement strategies that improve QOL of diabetic Pts. is crucial to delay or prevent formidable issues [56].A systematic review reported that diabetic patients had a lower related QOL than healthy people and those with better socio-economic status and better control of cardiovascular risk factors had better health related QOL [57]. Fahad Al-Shehri study concluded that most diabetic patients (78.7%) had negative (i.e., unfavorable) audit of diabetes dependent quality of life scores. Diabetic patients' age, education and occupation were not significantly associated with their QOL. Female patients had significantly worse QOL than male patients (p = 0.026). Married patients had significantly worse QOL compared with non-married patients (p = 0.012). Patients with type 2 diabetes had significantly worse QOL than those with type 1 diabetes (p = 0.029). The degree of diabetes control was significantly and directly associated with QOL score (p < 0.001). The worst QOL was expressed among poorly controlled diabetes while the best was among patients with excellent control [58]. Diabetic patients face great challenges in all quality of life dimensions. Epidemiologists, public health researchers, and health policy makers should work together to develop comprehensive programs for health promotion and disease prevention through increasing public awareness [59].The samples in current study were divided in to four categories or bio-functional age groups, Percentage of samples categorized in to the groups were 20-29- (4%); 30-39(56%); 40- 49 (32%); 50- 59 (8%). 92% were females and 8 % were males, 12 % were unmarried and 88% were married. According to the number of dependents 4 % had no dependents, 52% had 1 dependent, 32% had 2 dependents, 8% had 3 dependents, 4% had 4 dependents, which is not constant with study conducted by Levterova. et.al. found that less than half were females (52.9%), married (74.3%) and living in urban areas (61.4%) [60]. Type 2 DM has negatively affected all domains of quality of life of the study group [60]. Result of current study were agreement with this result where many of participants didn’t work, majority were female, nearly to half were aged more than 40 years, and 92% of the sample were having hereditary disease & taking regular treatment, high percentage of heredity diseases demonstrated that consanguineous marriage still followed in south Saudi Arabia. Regarding their educational level, 20 % were illiterate, 12% able to read and write, 8% have preparatory school, 36% had attended secondary school & university graduates were 24%, this education level illustrate why nearly to two third weren’t work & or may be due to participants age . In this study 20% of samples were earning a monthly income less than 5000SR, 72% were earning between 5000- 10000 SR, and 8% had more than 10000SR income, which indirectly showed that high prevalence of DM was noticed in low and moderate economic status.In the current study the researchers noticed that there is a significant difference between the pre-posttest mean scores regarding quality of life. Therefore patients can have a change in the quality of life if their knowledge level is improved by self-learning educational package. This result was concurrent with systematic review study that showed a structured diabetes education has a positive impact on biomedical and quality of life on diabetic patients especially with some degree of reinforcement at additional points of contacts [47]. A significant increase in general health perception, physical functioning, social functioning, pain, and mental health; however, there was no statistically significant increase in energy and fatigue and role emotional [48]. The present study result were constant with this result where we found an improvement in participants QOL domains after administer an illustrated self-learning package.

5. Conclusions

- The main result of current study were indicates to:1. Majority of participants were female and had a hereditary family diseases with compliance to daily treatment (92%), aged more than 30 years & dependent on family members on response to daily living activities (96%).2. Nearly 2 third didn’t working (64%), only 24% were graduated from university and nearly three quarter were following government health care sectors with monthly family income ranged between 5-10SR (72%).3. A posttest total QOL mean score was statistically difference improved after administering a self-illustrated learning package compared to a pretest mean score (P value < 0.05) that supported a research hypothesis.4. Majority of QOL dimensions posttest were improved compared with pretest.

6. Recommendations

- DM had worst impacting in QOL. Based on results of present study and research hypothesis, we concluded that - There is a highlight needs for take steps in order to improving diabetic Pts. QOL.- An educational self-learning illustrated package can serve as a choice method for patients with diabetes to enhance their disease-related knowledge, skills and compliance to strategies that improve QOL.- There is a needs to initial QOL assessment, enhance awareness for newly diagnosed Pt. and periodically.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML