-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Diabetes Research

p-ISSN: 2163-1638 e-ISSN: 2163-1646

2016; 5(5): 102-121

doi:10.5923/j.diabetes.20160505.03

Effects of Diabetic Education on Body Mass Index, Fasting Blood Sugar and Knowledge Gained by Diabetic Patients in Central Hospital Nampula

Madhumati Varma

Ministry of Health Moazambique, Central Hospital, Nampula, Mozambique

Correspondence to: Madhumati Varma, Ministry of Health Moazambique, Central Hospital, Nampula, Mozambique.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

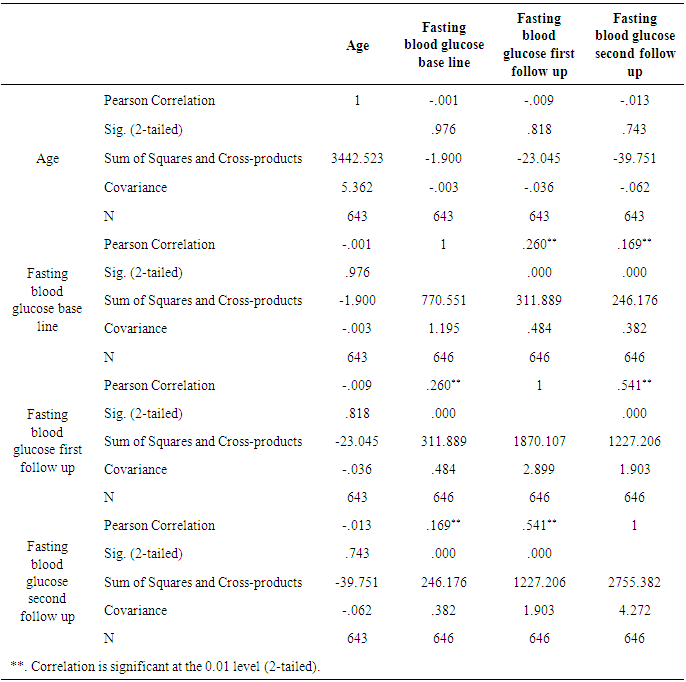

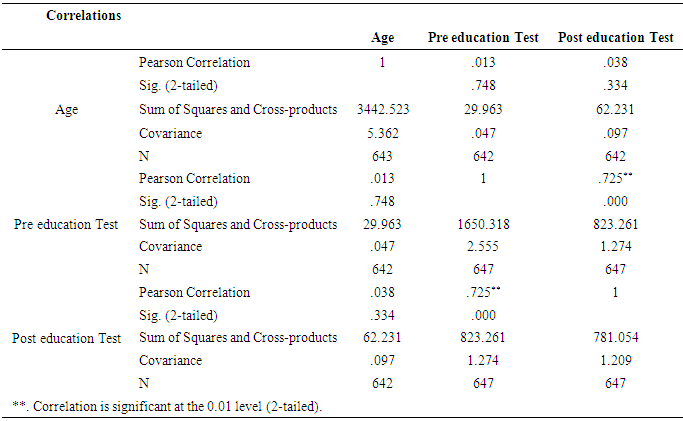

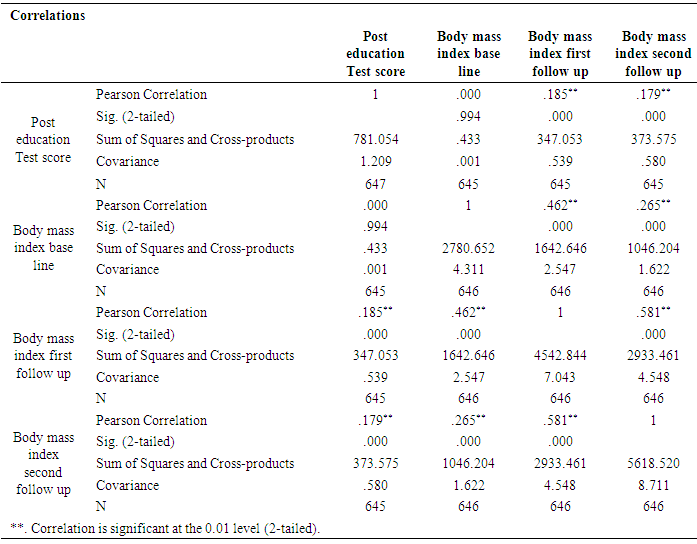

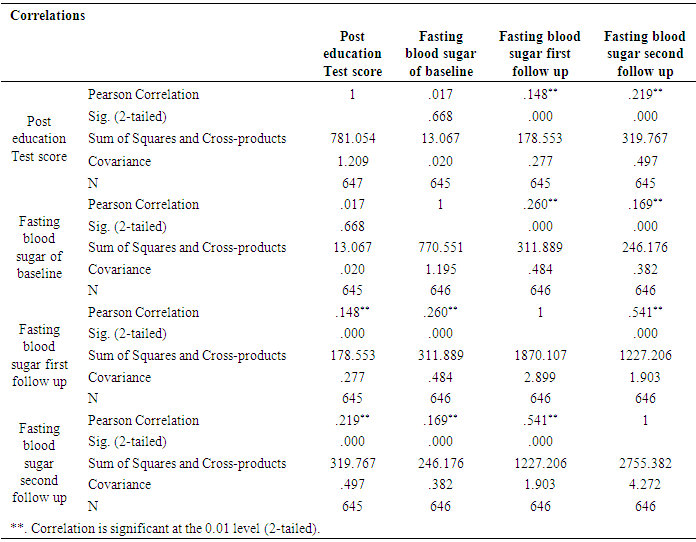

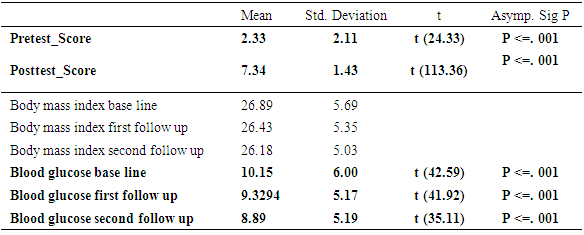

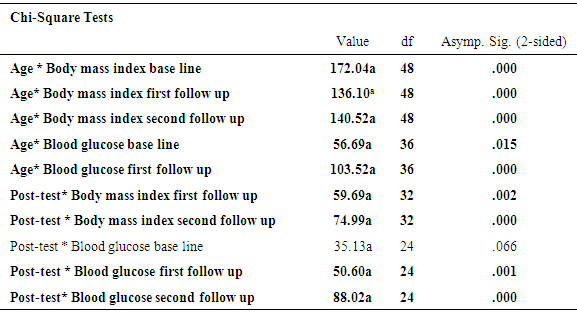

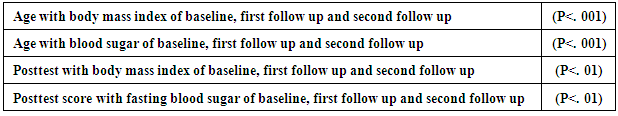

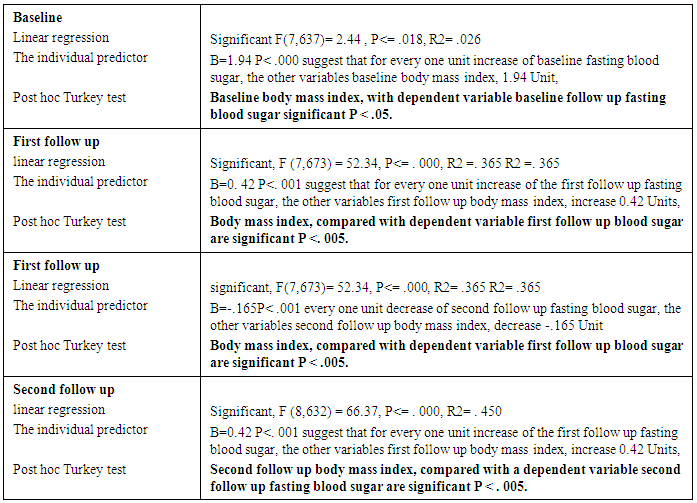

Mozambique, has 274,700 diabetic patients and 9716 deaths due to diabetes, according to a report of 2015 (IDF 2015). There is a poor knowledge of non-pharmacological treatment of diabetes mellitus among the diabetic population. This is Interventional study, 648 of the participants of diabetes mellitus in out-patient diabetic clinic in hospital central Nampula, the participants taken according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, completed the pre-test at baseline and post-test after the second follow up session of education, during each session of education body mass index and fasting blood sugar were recorded. Education commenced with instruction in groups of each session followed by individual advice sessions for each patient with different specialists. The present study found that educational intervention of diabetes was highly effective to gain knowledge of diabetes compare pre-test and Post-test score (P <. 001), fasting blood sugar and body mass index significantly decreased from baseline in the second follow up (P <. 001). Age was significantly correlated with body mass index and fasting blood sugar (P<. 001). Posttest with body mass index and fasting blood sugar was significantly correlated (P<. 01). A post hoc Turkey test of body mass index when compared with fasting blood sugar found significantly (P=. 05) at baseline, at first follow up (P=. 005) and at second follow up (P=. 005).The present study found that educational intervention was highly effective in controlling body mass index, fasting blood sugar and improves knowledge of diabetes among participants of diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Blood sugar, Body mass index, Effect education, Control, Participants

Cite this paper: Madhumati Varma, Effects of Diabetic Education on Body Mass Index, Fasting Blood Sugar and Knowledge Gained by Diabetic Patients in Central Hospital Nampula, International Journal of Diabetes Research, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2016, pp. 102-121. doi: 10.5923/j.diabetes.20160505.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

- WorldwideThe Global report from the World Health Organization (WHO), published in 2016, estimated that 422 million of the adult population lives with diabetes the number of diabetic patients has dramatically increased 4 times over in the adult population, compared to 108 million in 1980. Diabetes Mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder, which is caused by partial deficiency or total deficiency of insulin. Diabetic mellitus could be diabetes, which is type 1 complete deficiency of insulin and diabetes type 2, partial deficiency of insulin with receptor of insulin not functioning to facilitate enter glucose into cells for utilization and formation of units of energy. WHO has estimated that the number of diabetic patients will double by 2030. Diabetes is increasing more rapidly in low and medium income groups than higher income groups as well as in, developing countries compared to European countries, where there is less prevalence of diabetes. The top five countries with the highest prevalence of diabetes. Include the following: India, China, USA, UK, Bazile and Indonesia. Diabetes Type 1 most common in Scandinavian populations, Sardines, and Kuwait, and less common in Asia, Latin and European population. Mozambique Mozambique is located on the East coast of Africa (Wikipedia 2016). There are 274,700 diabetic patients and 9716 deaths due to diabetes, according to a report of 2015 (IDF 2015). This country is the setting for this study. There is the prevalence of obesity, poor knowledge regarding diabetes and lack of awareness of complication of diabetes. Most of the population uses traditional healer for treatment of diabetes. There are unhealthy food habits, sedentary lifestyle in urban population and increased economic growth amongst professions related to office work, which is one of the risk factors that causes diabetes and its complications. There are no professional health, diabetes educators and patients have little or no knowledge of self-management, adherence of treatment, awareness of complication. Among the group of patients who seek care in public hospitals, many are poor and cannot afford the cost of medication or healthy foods. There is an 80 dollar expenditure allotted to each patient of diabetes from the country’s Ministry of Health and supported by the government. Additionally, the ministry of health provides free medication for all chronic diseases, including diabetes and hypertension. Currently, there is no study that has been done on the effects of education in various modalities of diabetes for patients and its outcome. Accordingly, there is an extreme need to educate patients of diabetes to improve diabetic control and reduce its complication.

1.2. Objective and Hypothesis

- Problem:The population for this study are diabetic patients in the Central Hospital Nampula in Mozambique, who are from low and medium income groups. This group of patients has limited sources of incomes and, completely depends on the diabetic pharmacological treatment of the government hospital pharmacy, which gives medication free of cost. In the country of Africa, there is a generally poor health education regarding the diabetes. There are no professional diabetic health educators and patients receive advice from doctors and dieticians regarding their diets and directions on how to use their prescriptions of medicine so as to continue treatment at home. Due to the large size of patient loads in outpatient consultations of diabetes, it is not possible to sit with each patient and provide specific health education about diabetes. Also, these groups of patients do not access of the internet to seek their own self-education from different sources. It is clear that when diabetic patients only utilize pharmacological treatments that it is not sufficient to control diabetes and complication [3].Objective:1. There is a need for lifestyle modification, knowledge of diabetes and its complication, as chronic disease, so that patients can ability to detect small symptoms of complication and present physician, adherence of treatment and its important.2. There are different types, categories, and levels of controlled diabetic patients and the each type requires different types of education, depending on complications and diseases associated with diabetes. There following are the clinical categories patients:1. Good control over blood sugar and without complication.2. Fair/not controlled blood sugar with or without complication.3. Good control of blood sugar and without complication, but other disease example HIV treatment, CVA etc.Question statementTo conduct the study, used dependent variable fasting blood sugar and independent age, body mass index. Positive hypothesis, the positive correlation of control of fasting blood sugar change of lifestyle modification includes diet and exercise. The positive correlation with control of fasting blood sugar to improve body mass index. The knowledge of diabetes could help in controlling diabetes and blood sugar in case implemented knowledge of diabetes in life style. Null hypothesis, the diabetes more common with age of 45-60 but not uncontrolled by increase of age. The various reasons which can responsible for uncontrolled fasting blood sugar, in case not implemented knowledge of diabetes in life style.Assumption and limitationThere is a need to implement before each consultation of control of diabetes for writing the prescription of medicine and controlling complication. There should be a 15 minute session of education to reemphasized, remember to patients to continue habits which helping to control diabetes. It is seen continues education help to keep continue positive habits to control diabetes. As increase period after education, some of patients come back to the same stage as they were started.There were limitations as Mozambique is developing country as limited resources in hospital. To minimized expenditure, there are available only fasting blood sugar. There is no concept of doing the regular postprandial blood sugar. There was some time, none availability of reagent in the laboratory to evaluate blood sugar during the period of study. That makes statically results different from which was accepted. To choose topic also forced to see the available facility in a public hospital.

2. Method

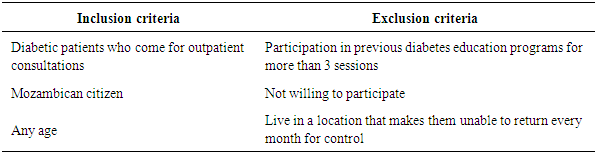

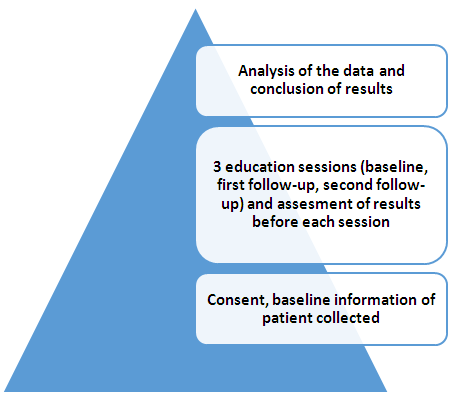

- This study was conducted on regular patients of the diabetic outpatient department of the Central Hospital of Nampula. The study investigated the effects of three sessions of the diabetes education program (baseline, first follow-up and second follow-up) on each patient at one-month intervals. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation in the education program are listed below.Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study

|

| Figure 1. Conceptual framework |

3. Results

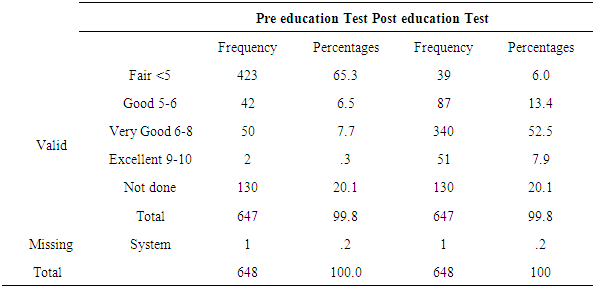

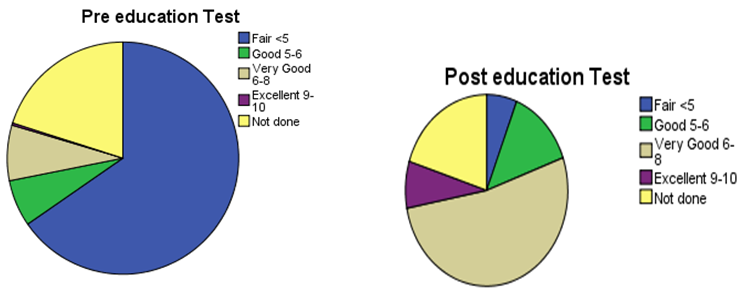

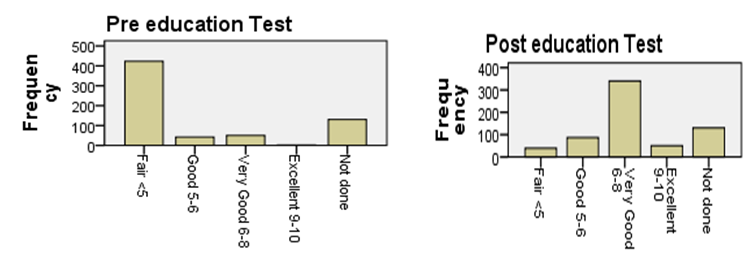

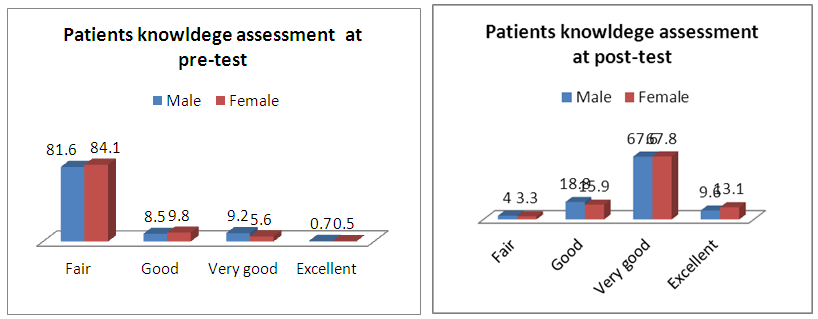

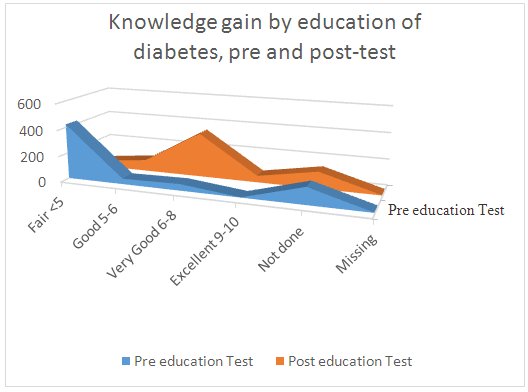

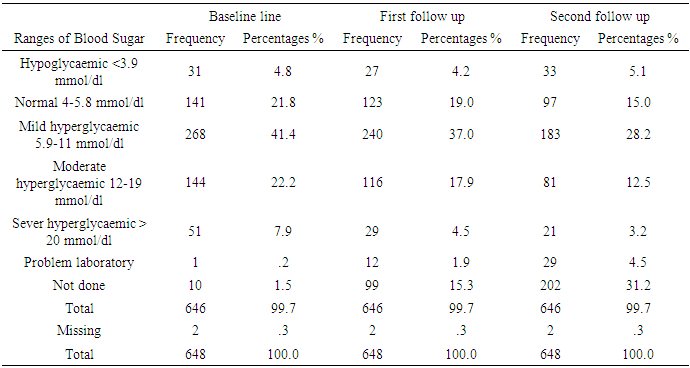

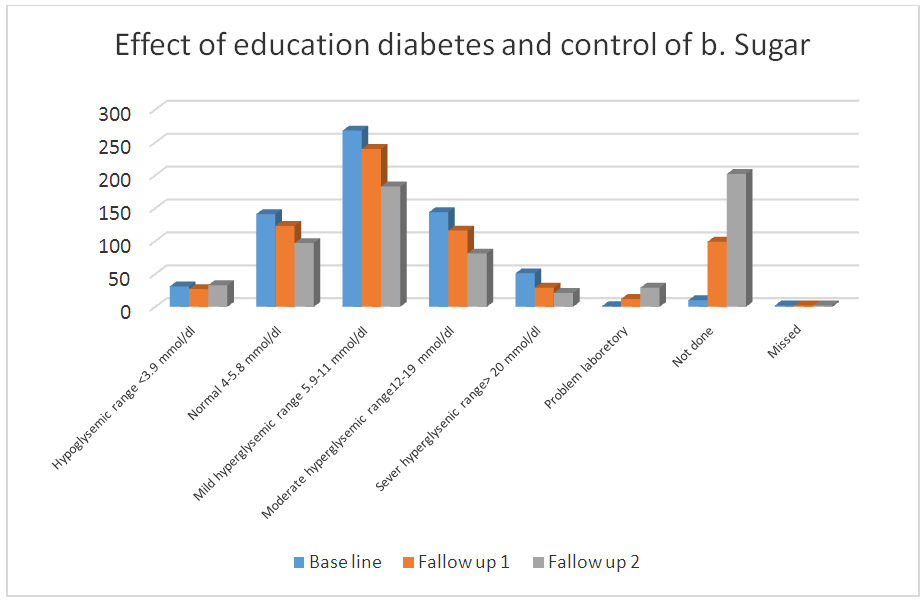

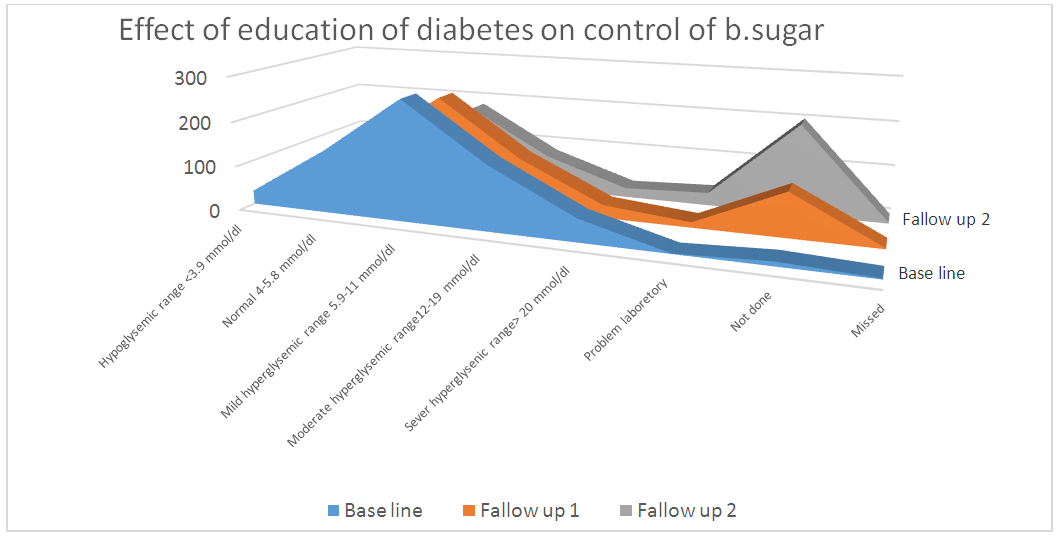

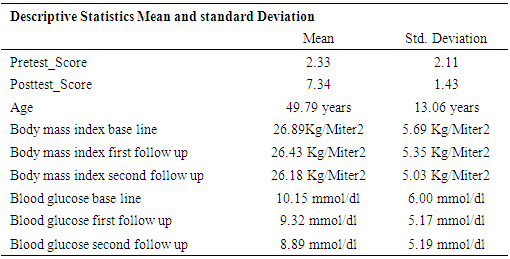

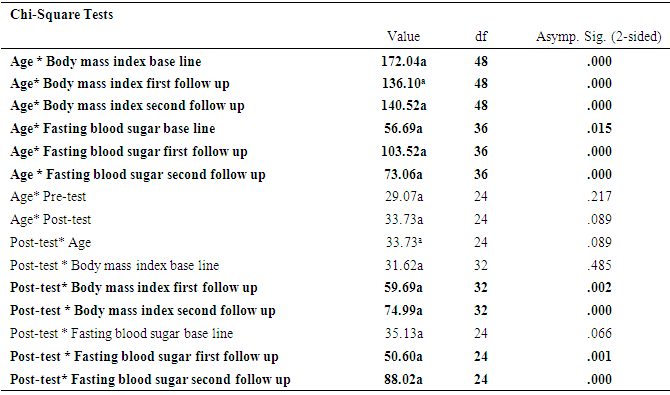

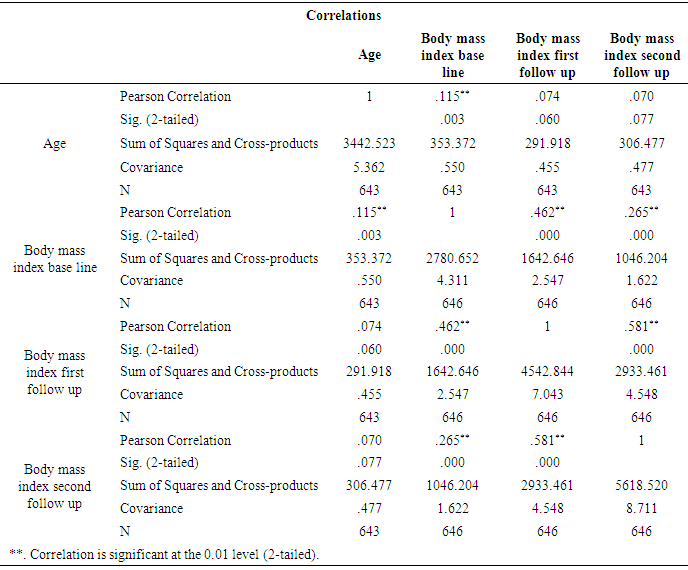

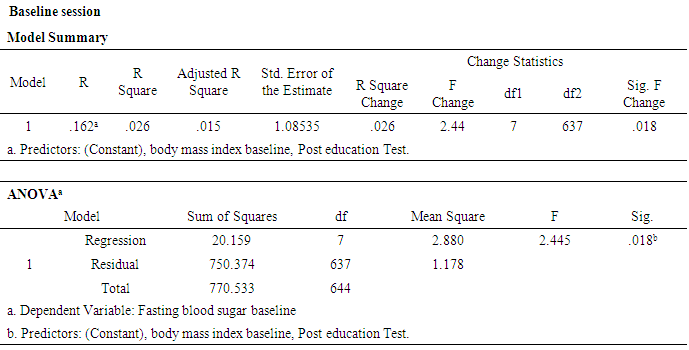

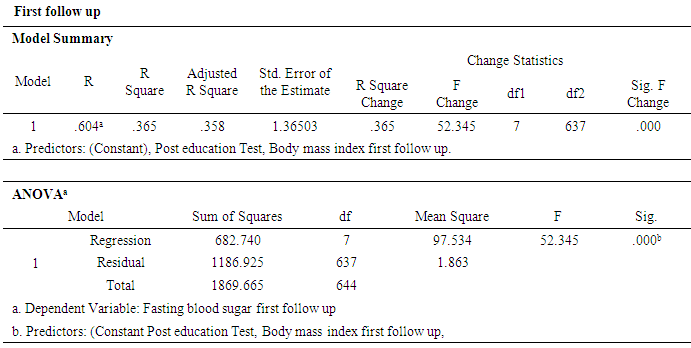

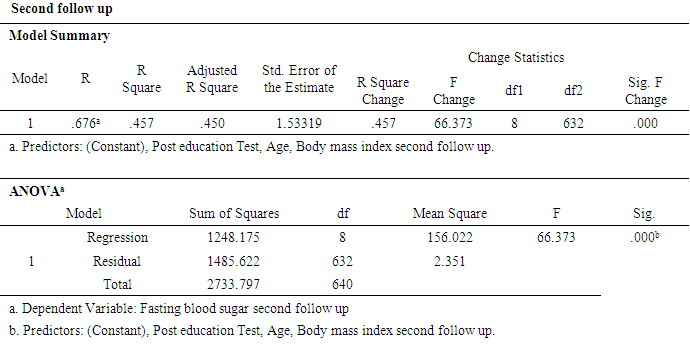

- A sample of 648 participants was taken for this study. This study was conducted on regular patients of the diabetic outpatient department of the Central Hospital of Nampula. The study investigated the effects of three sessions of the diabetes education program (baseline, first follow-up and second follow-up) on each patient at one-month intervals. The inclusion criteria for participating in the diabetes education program dictated that patients should be in the OPD, willing to participate in the education sessions and willing to give consent to be included in the study. Participants were excluded if they had already completed three sessions of education or if they lived in a district that made it impossible for them to return within one month to the next education session. Amongst the group instructors were a diabetologist, dietician, psychologist, physiotherapist, and diabetic nurse. There was a pre-test questionnaire that aimed to assess the existing knowledge of diabetes before starting the baseline education session. The same questions were asked after the completion of the second follow-up education session. There were various variables to assess from baseline to second follow up education session. The variables were assessed age groups, body mass index, blood pressure, and fasting blood sugar in patients with diabetes mellitus.Descriptive analysis of Pre-test and post-test score at before baseline and after second follow upA sample of 648 patients with diabetes mellitus, those who had participated in educational sessions concerning diabetes mellitus, was taken for study in order to determine the effect of education on improving knowledge levels in diabetes. The analysis of knowledge increased of diabetes mellitus among participants was performed pre-test at the beginning baseline, and post-test at the end second follow up. The results are shown in Table 2, below. Briefly, the percentage of patients with a fair level of knowledge (65.3%) increased from beginning of baseline to very good level of knowledge of diabetes by 52.5% at the end of the second follow up.

|

|

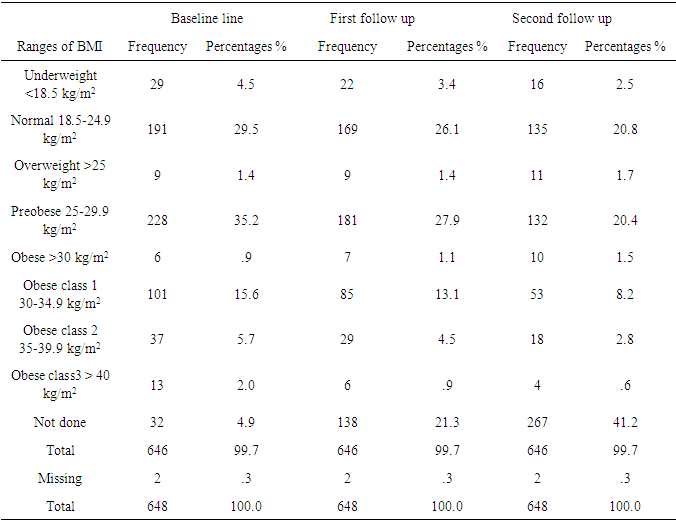

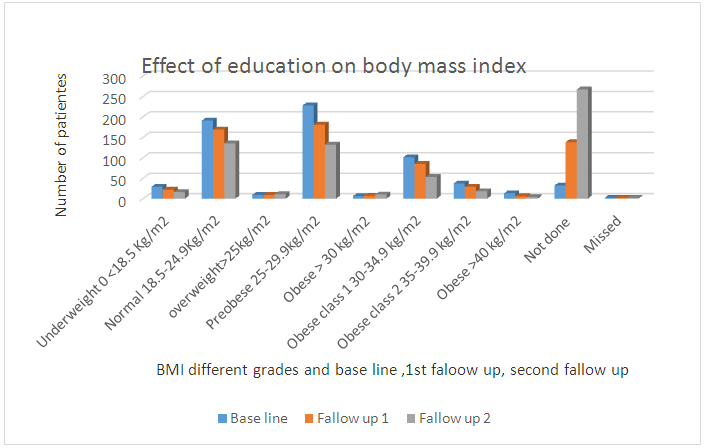

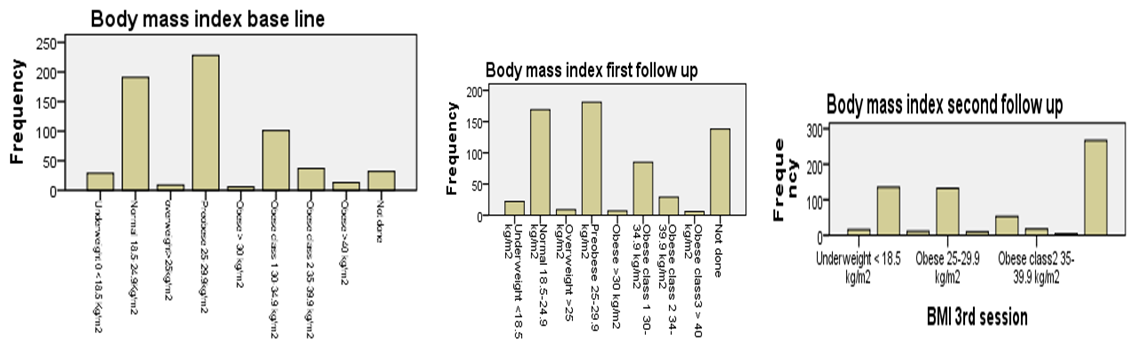

| Figure 3.1. Bar chart: In the above charts we see that the distribution of the compared body mass index at baseline, first follow up, and second follow up after education among participants |

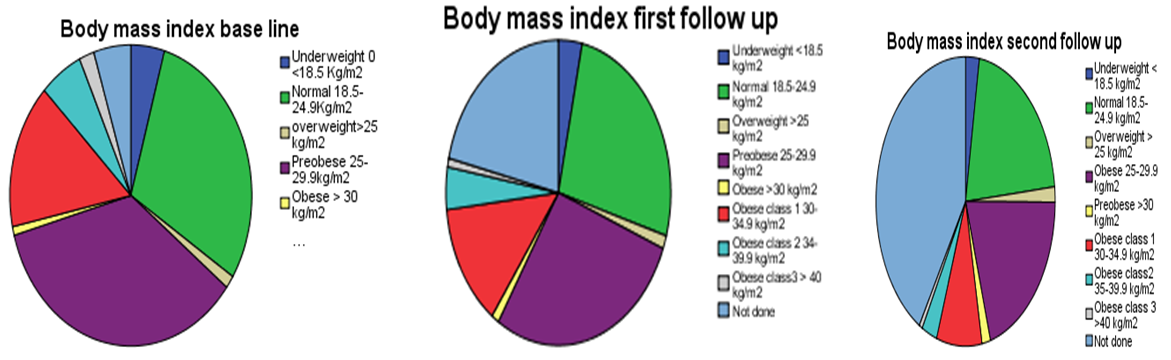

| Figure 3.2. Pia chart: In the above charts we see that the distribution of the compared body mass index at baseline, first follow up, and second follow up after education among participants |

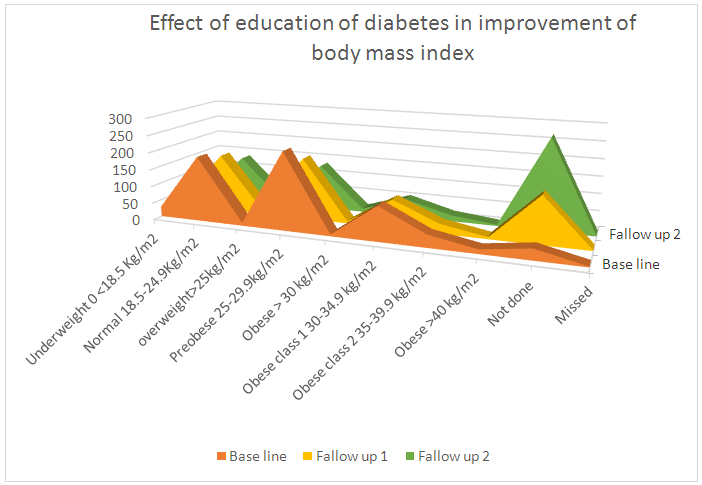

| Figure 3.4. Linear chart: In the above charts we see that the distribution of the compared body mass index at baseline, first follow up, and second follow up after education among participants |

|

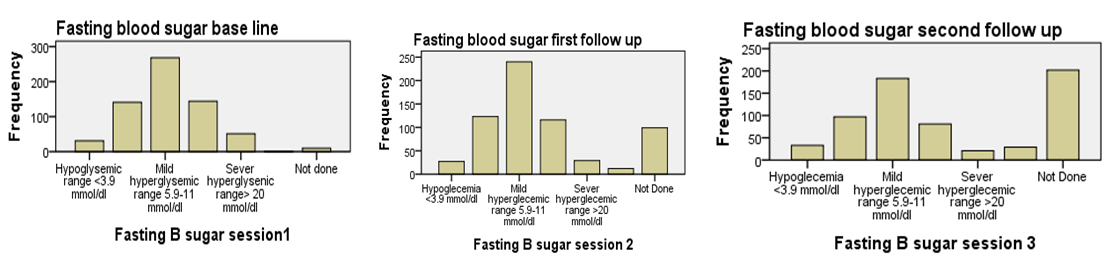

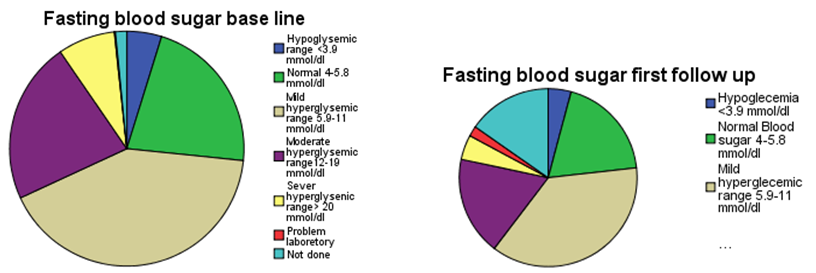

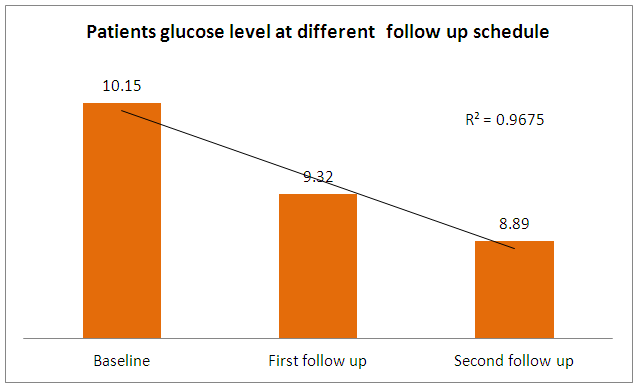

| Figure 4. Bar chart: In the above charts we see the distribution of comparing fasting blood sugar scores at baseline, first follow up, and second follow up after diabetes education among participants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Summary of Main Findings

- A sample of 648 participants was taken for this study. This study was conducted on regular patients of the diabetic outpatient department of the Central Hospital of Nampula. The study investigated the effects of three sessions of the diabetes education program (baseline, first follow-up and second follow-up) on each patient at one-month intervals. The inclusion criteria for participating in the diabetes education program dictated that patients should be in the OPD, willing to participate in the education sessions and willing to give consent to be included in the study. Participants were excluded if they had already completed three sessions of education or if they lived in a district that made it impossible for them to return within one month to the next education session. Amongst the group instructors were a diabetologist, dietician, psychologist, physiotherapist, and diabetic nurse. There was a pre-test questionnaire that aimed to assess the existing knowledge of diabetes before starting the baseline education session. The same questions were asked after the completion of the second follow-up education session. There were various variables to assess from baseline to second follow up education session. The variables were assessed age groups, body mass index, and fasting blood sugar.

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- The present study found that educational intervention was highly effective in controlling anthropometric parameters (BMI), as these had significantly decreased from baseline at the second patient follow up visit. Metabolic control (blood sugar) also showed a significant positive improvement from baseline in the second follow up visit. Finally, participants also showed an improvement in knowledge through diabetes education. This was assessed by a pretest prior to the commencement of education and a posttest after the completion of the second follow up educational sessions at the central hospital in Nampula. The knowledge provided by the education helped the participants to improve and change their lifestyle, especially their dietary and exercise habits, their psychological adjustment and their attitude to living with diabetes. Similar studies have previously been performed, with some comparable findings being reported. Newly diagnosed diabetic patients need self–management education, as this helps to increase their level of knowledge of diabetes and to provide them with skills to manage their diabetes life long, as it is a chronic condition [3]. A Cochrane review [25] concluded that a reduction in blood sugar concentrations, and increased knowledge of diabetes. A Cochrane review [25] concluded that through group education of diabetes patients get motivated, start adherence to treatment and understand diabetes. Meta analyses and the outcome of various studies have shown positive impacts after receiving diabetes education, and enhanced knowledge of diabetes has been presented by Ricci-Cabello et al. [17]. In order to promote diabetes awareness, self-care behaviors can be useful. [23] described innovative strategies for the improvement of diabetic control and glycemic improvement in Chinese patients through the continuing education of diabetes mellitus during patient examination and by increasing family involvement via diabetic knowledge [6], emphasized repeated diabetic education sessions to control and improve metabolic parameters. [8], using experimental and control groups regarding diabetes education.The effect of pre- and posttests, showed a reduction in HbA1c, but no effect on BMI. The present study found that participants had age group with diabetes mellitus was 41-60 years, of which 56% were male. A further study found that, regarding type of diabetes, diabetes mellitus type 2 was detected at the highest prevalence of 87.5%, however the prevalence of diabetes mellitus type 1 was 5.1%.

6. Conclusions

- Diabetes mellitus is a chronic and progressive disease, the prevalence of which is rapidly increasing. Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus may cause severe and irreversible untreatable complications, such as cardiovascular disease, retinopathy, nephropathy and cataract development. There is therefore a need to control anthropometric and metabolic parameters within an acceptable range in order to avoid the development of complications.Currently, it is not only wealthy countries that have a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus; low and mid-level economic counties are also progressively showing an increase in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus. This includes Mozambique, which shows a progressive increase in the number of patients with diabetes mellitus due to the lack of a healthy diet, a sedentary lifestyle and urbanization. Regarding patients with diabetes mellitus in a central hospital in Nampula, it was recognized that there was a need for organizing, education concerning diabetes, such as regarding the diabetic diet, increasing patient knowledge of diabetes to avoid the risks of complications, physical activity and its importance, and the psychological motivation to live with diabetes.Diabetes education was performed with general and specific groups of patients, according to the needs of the patients, the complications of the diabetes mellitus and other diseases associated with them. Three education sessions were organized, at an interval of one month (baseline, first follow up and second follow up). Each participant was evaluated in each session regarding their BMI, blood sugar. The statistical analysis showed strong significantly positive effects on controlling each of these parameters. Prior to the commencement of the baseline education session, an evaluation of the evolution of patient knowledge regarding diabetes mellitus (the pre-test) was performed. At the end of the second follow up, a post-test was performed, which showed strong significant increases in the knowledge of diabetes.The study also showed that the majority of the participants had diabetes mellitus type 2, were in the 41-60-year age group.Motivational quote“Exercise and diet can help prevent or even totally reverse metabolic conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular disease – only thing is, you’ve got to catch them young… You know, while these conditions are still of ‘impressionable minds’!”

– Deepak ‘The Fitness Doc’ HiwaleThere is currently a need to design a national policy and program for diabetes education. Clinicians and health educators should continue to reemphasize that patients with diabetes mellitus make healthy behavioral changes in order to control their diabetes and reduce the occurrence of complications.The limitations of this study include that some of the diabetic patients used traditional medications, some did not adhere to treatment, and some were lost to follow up, all of which can cause uncontrollable diabetes and increase the incidence of complications. Patients were very interested in taking medicine free of charge in a government hospital. Limitations were also found here, such as the intermittent non-availability in the results of blood sugar results due to a lack of laboratory reagents. Patients who lived district, distance from the hospital, not able to regularly attend three education sessions. Patients were more interested in obtaining medication than on lifestyle modification. Patients were generally from a poor or lower income group, and were unable to buy the recommended food. It was also noted that some patients had an insufficient economic condition to take small and frequent meals. Some of the patients presented with a delayed diagnosis, with irreversible complications.One of the strengths of this study is that patients, at the commencement of educational sessions, were encouraged to participate and to bring laboratory results and other activities to the follow up sessions by reminding them that they would receive prescription medicine at the end of the successful completion of all of the essential activities involved in the education sessions. This encouraged patients to take a further interest in the study, and the majority of these patients then implemented the required changes in their lives and achieved significant positive outcomes in controlling their diabetes.

– Deepak ‘The Fitness Doc’ HiwaleThere is currently a need to design a national policy and program for diabetes education. Clinicians and health educators should continue to reemphasize that patients with diabetes mellitus make healthy behavioral changes in order to control their diabetes and reduce the occurrence of complications.The limitations of this study include that some of the diabetic patients used traditional medications, some did not adhere to treatment, and some were lost to follow up, all of which can cause uncontrollable diabetes and increase the incidence of complications. Patients were very interested in taking medicine free of charge in a government hospital. Limitations were also found here, such as the intermittent non-availability in the results of blood sugar results due to a lack of laboratory reagents. Patients who lived district, distance from the hospital, not able to regularly attend three education sessions. Patients were more interested in obtaining medication than on lifestyle modification. Patients were generally from a poor or lower income group, and were unable to buy the recommended food. It was also noted that some patients had an insufficient economic condition to take small and frequent meals. Some of the patients presented with a delayed diagnosis, with irreversible complications.One of the strengths of this study is that patients, at the commencement of educational sessions, were encouraged to participate and to bring laboratory results and other activities to the follow up sessions by reminding them that they would receive prescription medicine at the end of the successful completion of all of the essential activities involved in the education sessions. This encouraged patients to take a further interest in the study, and the majority of these patients then implemented the required changes in their lives and achieved significant positive outcomes in controlling their diabetes.7. Contribution to Knowledge

- This study adds to the current body of knowledge regarding lifestyle modification and patient knowledge of diabetes. The education provided in this study allowed patients to understand diabetes and to control and minimize related complications.

8. Suggestion for Future Research

- However, a need remains to involve other departments in future studies, for example, emergency and intensive care medicine, district hospitals and the effect of education of diabetes of family members to control the diabetic of the patient, in order to see effect of education of diabetes to improve the knowledge of diabetes in public for primary prevention of diabetes in society.

References

| [1] | Diabetes Education Study Group (1977) History. Available at: http://www.desg.org/desg/about/history/ (Accessed: 14 August 2016). In-text citations: (DESG, 1977). |

| [2] | Norris, S., Lau, J., Smith, S., Schmid, C. and Engelgau, M. (2002) ‘Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control’, Diabetes care. 25 (7), pp. 1159–71. In-text citations: (Norris et al., 2002). |

| [3] | Association, A. D. (2002). Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care, 25(suppl 1), 33–49. doi:10.2337/diacare. 25.2007. S33In-line Citation: (Association, 2002). |

| [4] | Ellis, S.E., Speroff, T., Dittus, R.S., Brown, A., Pichert, J.W. and Elasy, T.A. (2004) ‘Diabetes patient education: A meta-analysis and meta-regression’, Patient Education and Counseling, 52 (1), pp. 97–105. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00016-8. In-text citations: (Ellis et al., 2004). |

| [5] | Braun, A., Sämann, A., Kubiak, T., Zieschang, T., Kloos, C., Müller, U.A., Oster, P., Wolf, G. and Schiel, R. (2008) ‘Effects of metabolic control, patient education and initiation of insulin therapy on the quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus’, Patient Education and Counseling, 73 (1), pp. 50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.Pec.2008.05.005. In-text citations: (Braun et al., 2008). |

| [6] | Mollaoğlu, M. and Beyazıt, E. (2009) ‘Influence of diabetic education on patient metabolic control’, Applied Nursing Research, 22 (3), pp. 183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.12.003. In-text citations: (Mollaoğlu and Beyazıt, 2009). |

| [7] | BJMP (2009) Impact of diabetes education and peer support group on the metabolic parameters of patients with diabetes Mellitus (type 1 and type 2). Available at: http://0x9.me/N0cmg (Accessed: 14 August 2016). In-text citations: (BJMP, 2009). |

| [8] | Salinero-Fort, M., Santa, C., Arrieta-Blanco, F., Abanades-Herranz, J., Martín-Madrazo, C., Rodés-Soldevila, B. and Burgos-Lunar, de (2011) ‘Effectiveness of PRECEDE model for health education on changes and level of control of HbA1c, blood pressure, lipids, and body mass index in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus’, BMC public health., 11. In-text citations: (Salinero-Fort et al., 2011). |

| [9] | Moattari, M., Ghobadi, A., Beigi, P. and Pishdad, G. (2012) ‘Impact of self-management on metabolic control indicators of diabetes patients’, Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 11 (1), p. 6. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-11-6. In-text citations: (Moattari et al., 2012). |

| [10] | Mash, B., Levitt, N., Steyn, K., Zwarenstein, M. and Rollnick, S. (2012) ‘Effectiveness of a group diabetes education program in underserved communities in South Africa: Pragmatic cluster randomized control trial’, BMC Family Practice, 13 (1). doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-126. In-text citations: (Mash et al., 2012). |

| [11] | Abdullah M., 2012, ‘Effects of the diabetes education program on metabolic Control among Saudi type 2 diabetic patients‘, Pakistan Journal Medical Science 2012 Vol. 28 No. 5 www.pjms.com.pk 925-930 (2012), viewed pjms.com.pk/index.php/pjms/article/view File//954. |

| [12] | zareban, I., Niknami, S. and Rakhshani, F. (2013) ‘The effect of the self-efficacy education program on reducing blood sugar levels in patients with type 2 diabetes’, Health Education & Health Promotion, 1 (1), pp. 67–79. In-text citations: (zareban, Niknami, and Rakhshani, 2013). |

| [13] | Kent, D., Melkus, D., Stuart, P., McKoy, J., Urbanski, P., Boren, S., Coke, L., winters, J., Horsley, N., Sherr, D. and Lipman, R. (2013a) ‘Reducing the risks of diabetes complications through diabetes self-management education and support’, Population health management. 16 (2), pp. 74–81. In-text citations: (Kent et al., 2013a). |

| [14] | Burke, S., Sherr, D. and Lipman, R. (2014) ‘Partnering with diabetes educators to improve patient outcomes’, Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity: targets and therapy. 7, pp. 45–53. In-text citations: (Burke, Sherr, and Lipman, 2014). |

| [15] | Makki Awouda, F., Elmukashfi, T. and Al-Tom, H. (2014) ‘Effects of health education of diabetic patient’s knowledge of diabetic health centers, Khartoum State, Sudan: 2007-2010’, Global journal of health science, 6 (2), pp. 221–6. In-text citations: (MakkiAwouda, Elmukashfi, and Al-Tom, 2014). |

| [16] | Pereira, D.A., Ma, N., Costa, S.C., Luíza, A., Sousa, L., César, P., Jardim, V., Sanches, L. and Jardim, S. (2014) ‘Effect of an educational intervention on the metabolic control of people with type 2 diabetes’, Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 18. In-text citations: (Pereira et al., 2014). |

| [17] | Ricci-Cabello, I., Ruiz-Pérez, I., Rojas-García, A., Pastor, G., Rodríguez-Barranco, M. and Gonçalves, D.C. (2014) ‘Characteristics and effectiveness of diabetes self-management educational programs targeted to racial/ethnic minority groups: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression’, BMC Endocrine Disorders, 14 (1), p. 60. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-60. In-text citations (Ricci et al., 2014). |

| [18] | Tidy, C. (2014b) Diabetes education and self-management programs. Patient. Available at: http://patient.info/doctor/diabetes-education-and-self-management-programmes (Accessed: 14 August 2016). In-text citations: (Tidy, 2014b). |

| [19] | Chrvala, C., Sherr, D. and Lipman, R. (2015) ‘Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of the effect on glycemic control’, Patient education and counseling. 99 (6), pp. 926–43. In-text citations: (Chrvala, Sherr, and Lipman, 2015). |

| [20] | Merakou, K., Knithaki, A., Karageorgos, G. and Theodoridis, D. (2015) ‘Group patient education: Effectiveness of a brief intervention in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary health care in Greece: A clinically controlled trial’, Health Education Research, 30 (2), pp. 223–232. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv001. In-text citations: (Merakou et al., 2015). |

| [21] | Disclaimer, I. D. F. (2015). Mozambique. Retrieved August 29, 2016, from http://www.idf.org/membership/afr/mozambique. In-line Citation: (Disclaimer, 2015). |

| [22] | Mendes, G., Nogueira, J., Reis, C., Meiners, D. and Dullius, J. (2016) ‘Diabetes education program with emphasis on physical exercise promotes significant reduction in blood glucose, HbA1c and triglycerides in subjects with type 2 diabetes: A community-based quasi-experimental study’, The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness. In-text citations: (Mendes et al., 2016). |

| [23] | Choi, T.S.T., Davidson, Z.E., Walker, K.Z., Lee, J.H. and Palermo, C. (2016) ‘Diabetes education for Chinese adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control’, Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 116, pp. 218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.04.001. In-text citations: (Choi et al., 2016). |

| [24] | Center, J. D. (2016, August 14). Diabetes education: Why it’s so crucial to care. Retrieved August 14, 2016, from http://www.joslin.org/info/diabetes_education_why_its_so_crucial_to_care.html. In-line Citation: (Center, 2016). |

| [25] | 5.5 general diabetes self-management and education (2016) Available at: https://www.icsi.org/guideline_sub-pages/diabetes/55_general_diabetes_self-management_and_education/ (Accessed: 14 August 2016). In-text citations: (5.5 general diabetes self-management and education, 2016) Retrieved August 29, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/.../Geography_of_Mozambi. |

| [26] | NDEP program overview. (2016, June 24). Retrieved August 29, 2016, from https://0x9.me/NoyVg Citation: (“NDEP program overview,” 2016). |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML