-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Diabetes Research

p-ISSN: 2163-1638 e-ISSN: 2163-1646

2016; 5(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.diabetes.20160501.01

Cross-Generational Diabetic Programming Using an Established LDLR–/– Mouse Model: Maternal Pre-Gestational Immunization Improves Glucose Homeostasis in their Offspring

Claudia Eberle1, 2, Christoph Ament3

1Hochschule Fulda – University of Applied Science, Fulda, Germany

2Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego (UCSD), La Jolla, USA

3Chair of Control Engineering, Augsburg University, Augsburg, Germany

Correspondence to: Christoph Ament, Chair of Control Engineering, Augsburg University, Augsburg, Germany.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In terms of targeting the epidemic wave of metabolic diseases, novel therapeutic approaches as well as specific strategies of prevention are urgently needed. Exposure to pathogenic influences induces pathogenic cross-generational diabetic programming and increased insulin resistance and diabetic conditions later in life, whereas maternal immunization with specific antigens may protect offspring. In this contribution a novel therapeutic approach by maternal immunization is evaluated in an established murine model. Male and female offspring of LDL receptor-deficient mothers immunized with mildly oxidized LDL prior to mating and non-immunized controls were compared. All offspring received identical low-fat diet after weaning, in order to model lifestyle impacts. Oral glucose tolerance tests were performed, plasma glucose and insulin levels were measured. Results show that glucose levels were reduced by 45.52 mg/dl (p = 0.018) at t = 60 min and peak plasma insulin levels dropped by 25.33 µU/ml (p = 0.03) at t = 15 min due to maternal immunization. Hence, glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity of the next generation benefit from maternal immunization. The analysis regarding offspring sex shows that fastening plasma glucose levels in female offspring were reduced by 53.03 mg/dl (p= 0.0003) compared to male, whereas fastening plasma insulin levels were increased by 12.37 µU/ml (p= 0.02). Improved female glucose tolerance is obtained at the expense of reduced insulin sensitivity. However, female and male offspring benefit significantly from maternal immunization, which constitute a promising therapeutic concept for the prevention of metabolic diseases.

Keywords: Cross-generational programming, Effect analysis, Immune modulation, Insulin resistance, Metabolic syndrome

Cite this paper: Claudia Eberle, Christoph Ament, Cross-Generational Diabetic Programming Using an Established LDLR–/– Mouse Model: Maternal Pre-Gestational Immunization Improves Glucose Homeostasis in their Offspring, International Journal of Diabetes Research, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.diabetes.20160501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The number of metabolic diseases are increasing worldwide in an epidemic manner. As a consequence, costs for therapy of diabetes are increasing [1] and sum up e.g. to 50 billion Euro per year in Germany [2]. New therapeutic approaches and strategies of prevention are urgently needed to stop the increase of metabolic diseases. An approach may arise from a therapeutic application of cross-generational programming, which was first observed regarding negative impacts to the next generation: Barker formulated the hypothesis [3] that lower birth weight is correlated to an increased risk of cardio-vascular diseases later in life, which was generalized as “Thrifty Phenotype Hypothesis” [4]. It has been shown that a metabolic disorder of the mother (e.g. diabetes) will affect the metabolic system of children in a negative way, such that the development of metabolic diseases in the next generation may be induced. The underlying epigenetic mechanisms have been explained as “Predictive Adaptive Response Hypothesis“ [5] and “Fetal Insulin Hypothesis” [6]. These negative mechanisms of cross-generational imprinting can be summarized as diabetic and metabolic programming [7].In order to develop therapies to prevent metabolic diseases in the next generation, one has to utilize the mechanism of metabolic programming in a positive way. First studies have shown that interventions in mothers may provide life-long benefits to offspring [8]. A novel approach is the immunization of mothers for example with naturally oxidized LDL (nLDL) [9]. In this approach immunization is completed prior to pregnancy. Therefore, it is not a direct fetal immunization, but a maternal immunization leading to a cross-generational impact by the subsequent programming of the fetus.In this study we will present the results of an LDL receptor-deficient (LDLR–/–) mouse model [9]. In order to quantify the cross-generational programming impact, we will introduce corresponding effects, and show their significances.In order to characterize the metabolic condition of offspring, a metabolic diet is applied to the offspring and an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is performed. Based on the OGTT a metabolic model can be identified and used to assess the effect of maternal immunization, e.g. the Minimal Model from [10], or more detailed models as in [11-13]. In contrast, in the experiments presented here, we utilized available plasma glucose as well as plasma insulin measurements to directly assess the effect of maternal immunization, without recurring to a metabolic model.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

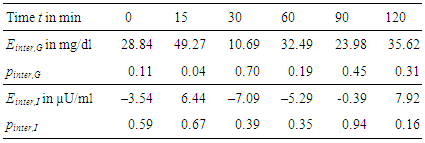

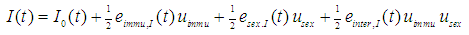

- In order to investigate a possible cross-generational impact from mothers to their offspring, experiments were carried out in age-matched LDL receptor-deficient (LDLR–/–) mice at University of California San Diego (UCSD). The colony was established from founders bred back into the C57BL/6 background for 10 generations. To determine the effects of maternal immunization in offspring of both genders under dietary conditions, we investigated the effects of immunization with naturally oxidized LDL (nLDL) in 24 immunized mothers (experimental group) versus 25 non-immunized mothers (control group), see Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Experimental setup |

2.2. Offspring Control

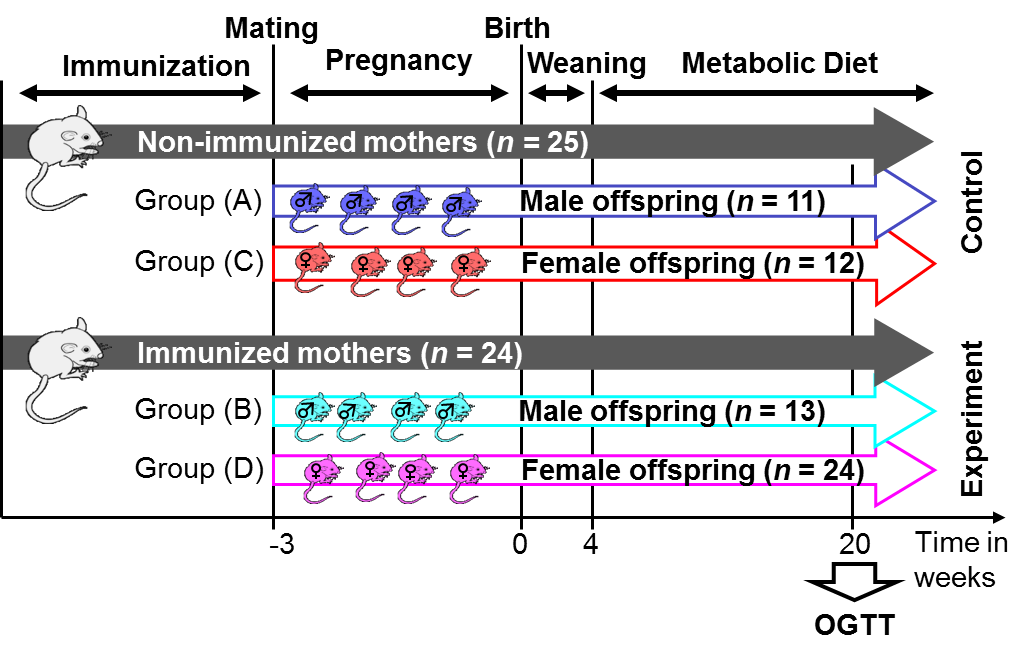

- During the growth of the offspring their weight, triglycerides and cholesterol was continuously measured. No abnormality have been observed for the animals included in this study. For confirmation Figure 2 shows the development of offspring bodyweight in groups (A) to (D). There is a difference regarding offspring sex, but no difference between immunized and non-immunized groups.

| Figure 2. Development of bodyweight in offspring groups (A) to (D) after birth (error bars denote standard deviation) |

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- For plasma glucose levels G(t) and plasma insulin levels I(t) during OGTT at time steps t = 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, the mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence interval (CI) have been calculated for all groups (A) to (D). In order to determine the CI a doubled-sided t-test is applied. For analysis we used the software tool Matlab with its Statistics Toolbox.

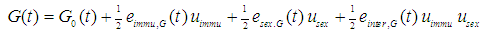

2.4. Effects Analysis

- Possible cross-generational effects of immunization from mothers to offspring should be assessed. For that purpose a linear regression model is fit into the data received from the murine model. It is assumed that the effect on glucose levels during OGTT is a linear function of maternal immunization uimmu, offspring sex usex and possible interaction of both:

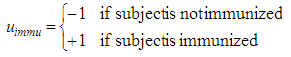

The same model approach is applied to plasma insulin concentration during OGTT:

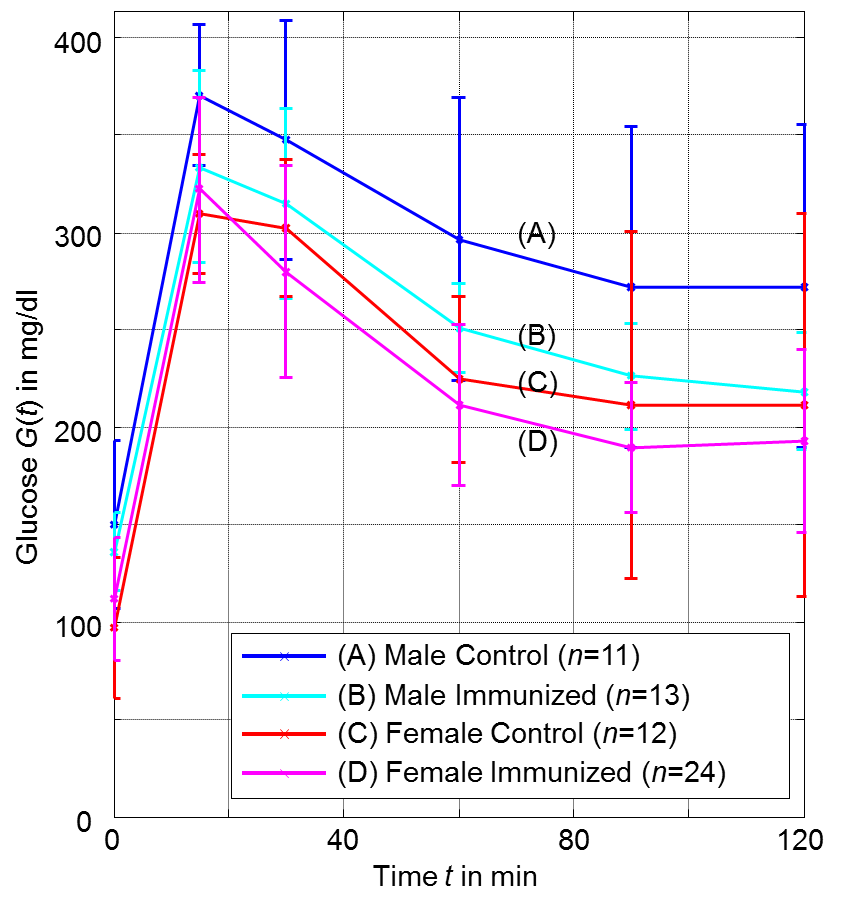

The same model approach is applied to plasma insulin concentration during OGTT: Therein, the influence of maternal immunization is defined as

Therein, the influence of maternal immunization is defined as and the influence of offspring sex is

and the influence of offspring sex is  .The coefficients e are called effects and were identified from the data of the animal model such that the model fit achieves the least square error [14], [15]. As a degree of reliance of the significance p of each effect e is calculated based on a double-sided t-test. G0(t) and I0(t) are average glucose and insulin levels that are unimportant for further analysis.

.The coefficients e are called effects and were identified from the data of the animal model such that the model fit achieves the least square error [14], [15]. As a degree of reliance of the significance p of each effect e is calculated based on a double-sided t-test. G0(t) and I0(t) are average glucose and insulin levels that are unimportant for further analysis. 3. Results

3.1. Offspring OGTTs

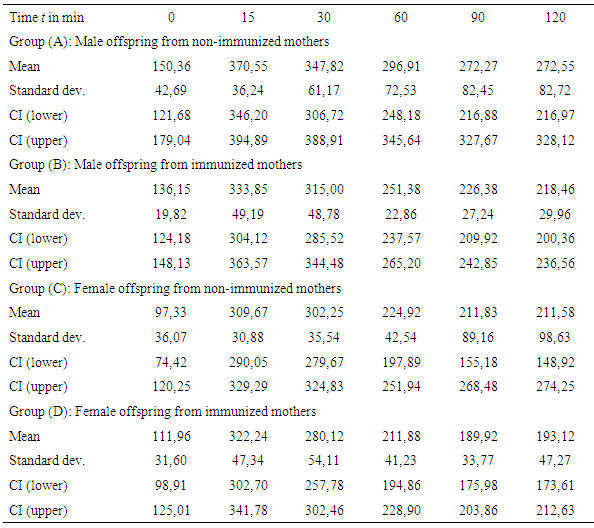

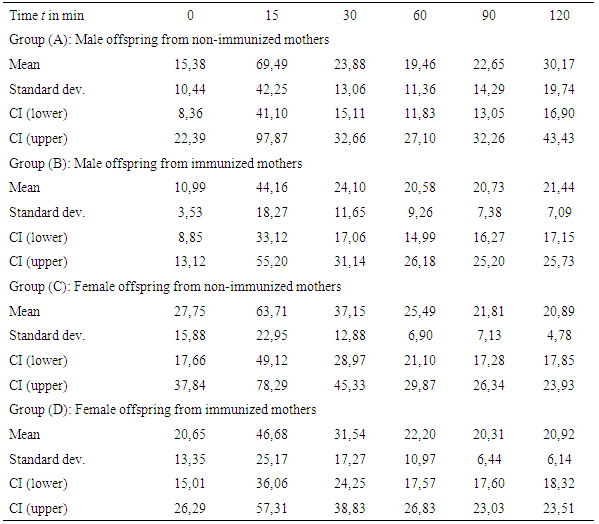

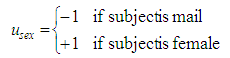

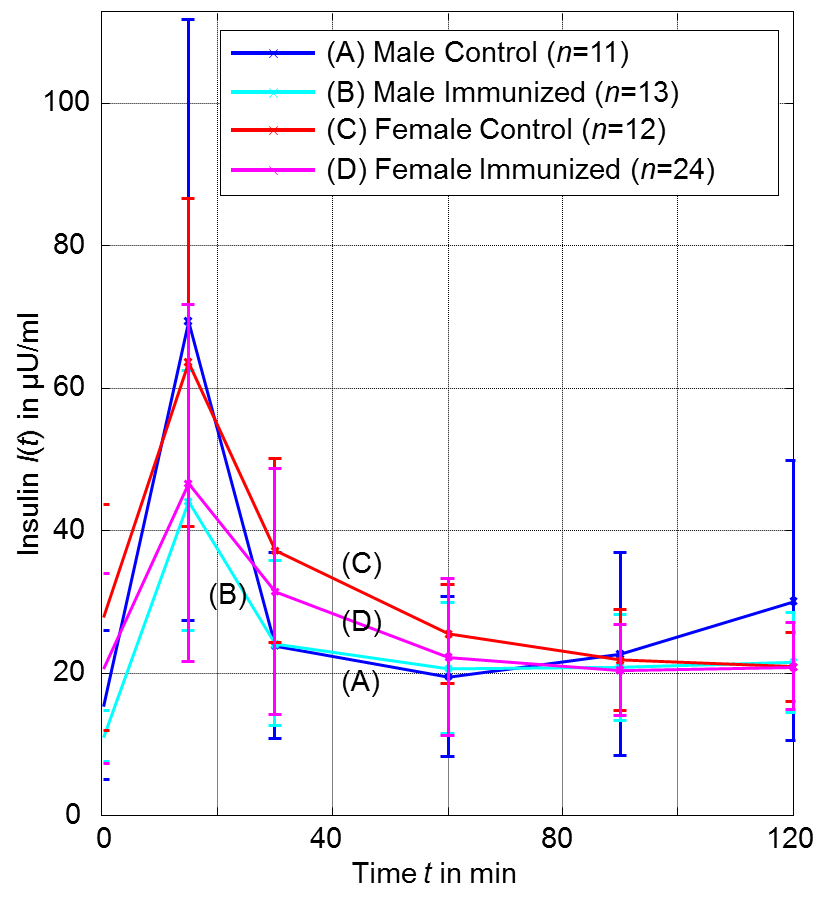

- Table 1 and Figure 3 show the plasma glucose levels of offspring in groups (A) to (D) during the OGTTs, whereas Table 2 and Figure 4 give the corresponding plasma insulin levels obtained simultaneously from the same OGTTs.

| Figure 3. Glucose response from OGTTs for offspring groups (A) to (D) at age of 20 weeks (error bars denote single standard deviation) |

| Figure 4. Insulin response from OGTTs for OGTTs for groups (A) to (D) at age of 20 weeks (error bars denote single standard deviation) |

|

|

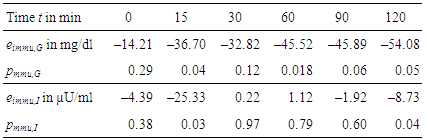

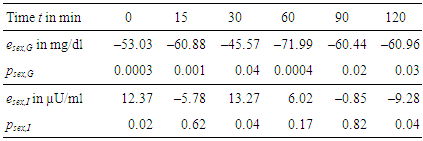

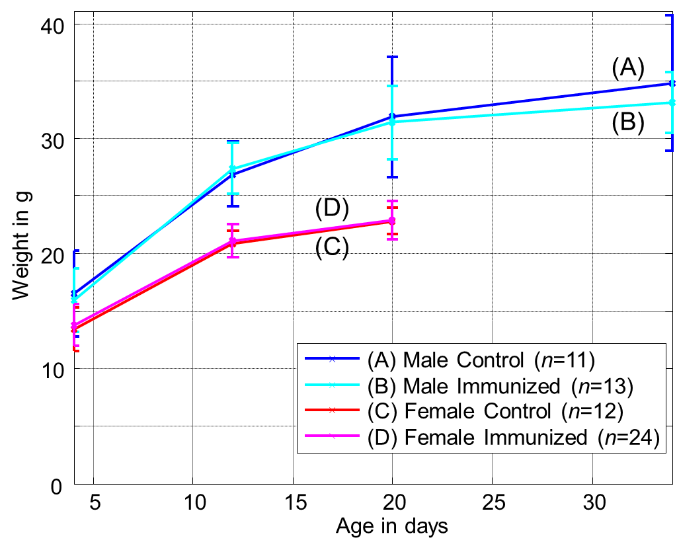

3.2. Effects of Immunization and Sex

- For each measurement within OGTT – which are glucose and insulin levels at t = 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min – effects e and their significances p have been calculated according to Section 2.4.Table 3 gives the numerical results for the effect of immunization, Table 4 for the effect of sex, and Table 5 for the combination of both effects, respectively.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Maternal Immunization

- As shown in Table 3 we observe a decreasing effect of maternal immunization to plasma glucose levels in offspring at all time-points. This is the most important result: Maternal immunization is able to improve glucose tolerance in offspring at an age of 20 weeks, leading to lower plasma glucose levels throughout all samples of an OGTT. This difference is not significant in fastening glucose levels (in Table 3 at t = 0 min; p = 0.29). In the dynamic response phase of the OGTT, i.e. at t = 15, 60, 120 min the reductions are significant (p ≤ 0.05) with the best significance of p = 0.018 at t = 60 min. In the murine model the lowered glucose levels in offspring of immunized mothers show that their plasma glucose clearance of the initial oral glucose excitation works more efficiently, leading to an improved glucose tolerance. In comparison to the control group, this is obtained by maternal immunization. Maternal immunization is completed before pregnancy (Figure 1). Therefore, it is not a direct “fetal immunization”, but, a two-step process of a maternal metabolic adjustment by immunization followed by a fetal imprinting of offspring.The metabolic diet administered to offspring before OGTTs (Figure 1) may model lifestyle impacts to a subject. If so, nLDL immunization may protect against later lifestyle risks. At that point it could not be excluded that lower glucose levels are reached at the expense of increased insulin levels. This way of glucose reduction would most probably lead to insulin resistance and metabolic diseases like diabetes type 2 later in life. However, overall effects on insulin levels (Table 3, two last rows) do not support this concern and actually show reduced values at t = 15 and 120 min. This underlines the positive impact of maternal immunization: An increased insulin sensitivity also helps to lower the plasma insulin levels, e.g. the peak level at t = 15 min within OGTT. This suggests that not only glucose tolerance, but also insulin sensitivity benefits from maternal immunization.

4.2. Effect of Offspring Sex

- The analysis regarding offspring sex (Table 4) shows that all female offspring glucose levels are much lower than male ones. Hence, there is a sex-specific difference in offspring. These gender effects are significant and higher than immunization effects for all samples during OGTT. This is confirmed by high significances in Table 4. Female offspring achieve better glucose tolerance. The effects of sex regarding plasma glucose and plasma insulin are most significant for the fastening values (Table 4, t = 0 min). But, fastening insulin is significantly increased. In female offspring improved glucose tolerance is achieved at the expense of reduced insulin sensitivity.It may concluded that offspring sex determines fastening plasma levels, whereas maternal immunization improves the dynamic metabolic response in offspring.

4.3. Coupled Effect

- Lowest plasma glucose levels are reached for female offspring of immunized mothers (group D). But, the analysis of coupled effects in Table 5 show, that both effects of immunization and sex cannot be fully superimposed independently. Coupled effects will be different from zero, if the combination of effects has an additional impact. Positive coupled effects in plasma glucose levels are obtained for all time points, see Table 5. This relativizes the glucose lowering effects observed for “immunization” as well as for “female”. Coupled effects for plasma insulin levels are small and not significant.

5. Conclusions

- In the presented murine model a beneficial effect in offspring from maternal immunization with nLDL could be shown. The OGTTs shows that the glucose tolerance as well as the insulin sensitivity could be improved. The corresponding effects are significant.It could also be seen that after the metabolic diet has been completed, female plasma glucose levels are significantly lower than male.In order to analyze immunization to plasma glucose, the sample at t = 60 min is most sensitive and is recommended as a reference. To assess immunization effects in plasma insulin the peak value at t = 15 is the best choice. Most significant differences between female and male offspring groups are found in fastening glucose and insulin levels.This study demonstrates the potential that maternal immunization can have to their offspring. Regarding mothers, further research can be geared to optimize the immunization procedure. Dosage and time-window should be varied to find the most promising therapy. Regarding offspring, long-term analysis may help to understand the impact e.g. to the cardiovascular system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to thank Wulf Palinski and his team at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) for the support of this work. Also the animal experiments have been performed at UCSD. C.E. was supported by a German Cardiac Society Research Fellowship.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML