-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Diabetes Research

p-ISSN: 2163-1638 e-ISSN: 2163-1646

2015; 4(2): 23-30

doi:10.5923/j.diabetes.20150402.01

Explanatory Models of Diabetes Mellitus and Glycemic Control among Southwestern Nigerians

A. Otekeiwebia1, 2, M. Oyeyinka1, 2, A. Oderinde2, C. Ivonye2

1Department of Family medicine, Lagos state University teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria

2Department of Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA

Correspondence to: A. Otekeiwebia, Department of Family medicine, Lagos state University teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disease with serious health and economic consequences. Patients with diabetes mellitus are often placed on a complex treatment program including life style modification, pills and or injectable such that the control of the illness will depend on patient’s personal behavior. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between glycemic control, medication taking behaviors and patients’ explanatory models of their illness. The study was a hospital cross sectional study among 98 patients with diabetes mellitus on oral hypoglycemic agents at a University Teaching Hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. Ethical approval was obtained from the Local Research and Ethics committee prior to commencement of the study. Patient’s sociodemographic characteristics, illness duration, Illness explanatory models and medication taking behaviors were collected after an informed consent was obtained. Explanatory models of diabetes was assessed using the Illness Perception Questionnaire on diabetes mellitus (IPQ-R), medication taking behavior was measured by pill counting and an average blood glucose was used as a surrogate of metabolic control among the cohort. Associated between explanatory models of diabetes, medicating behaviors and average glucose levels was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. A significant negative correlation was observed between metabolic control, adherence, illness coherence, personal control, treatment control, timeline acute/chronic and disease consequence. A positive correlation was found between glycemic control, emotional representation, external attributions such psychological and chance attributions. Duration of illness was associated with high score on disease consequences and course. However, there was no significant correlation between components of the illness explanatory models and age, gender or educational status. Explanatory models consistent with biomedical disease model of diabetes were associated with good medication taking behavior and good glycemic profile. These beliefs are modifiable and are target for educational interventions to improve self-care behaviors and metabolic control.

Keywords: Explanatory models, Diabetes mellitus, Medication taking behavior, Southwestern Nigeria

Cite this paper: A. Otekeiwebia, M. Oyeyinka, A. Oderinde, C. Ivonye, Explanatory Models of Diabetes Mellitus and Glycemic Control among Southwestern Nigerians, International Journal of Diabetes Research, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2015, pp. 23-30. doi: 10.5923/j.diabetes.20150402.01.

1. Introduction

- Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder of multiple etiologies characterized by chronic hyperglycemia with disturbances of carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both [1]. Diabetes mellitus constitutes a significant health and socioeconomic burden for patients and the health care system. The prevalence of this disease is projected to grow from 171 million in 2000 to 300 million by 2025, and the number of adults affected in developing countries is projected to grow by 170% from its 1-8% prevalence in the same period, with a greater increase expected in Africa and Asia [2]. In 2011, 14.7 million adults in the African Region were estimated to have diabetes, with Nigeria having the largest number (3.0 million) and these numbers are expected to rise [3]. The prevalence Diabetes in Southwestern Nigeria ranges from 4.76% in Ile-Ife of Osun State to 11.0% in urban Lagos. [4, 5] The economic burden of this illness is enormous in terms of the direct cost of monitoring, glycemic control and management of cardiovascular, renal, and neurological complications. [6] Management of Diabetes often involves medical therapy in combination with life style modifications. However, the effectiveness of these treatment modalities is dependent on rate of adherence and poor adherence has been identified as the major reason for suboptimal glycemic control.Adherence, defined as an “active, voluntary, and collaborative involvement of a patient in a mutually acceptable course of behavior to produce a therapeutic result [7]. It is based on choice and mutuality in goal setting, treatment planning, and implementation of the regimen. Studies have demonstrated that persistence with Diabetes Mellitus medications over time is poor, with adherence rate ranging between 36% and 93% [6-12]. In a retrospective study of an employer-sponsored prescription coverage program, 37% had discontinued Diabetes Mellitus medication altogether by the end of first year [9], these findings are striking given the fact that, with their prescription insurance coverage, subjects do not bear the medication costs which forms a common barrier to adherence. Individuals who do manage to adhere to their regimens may succeed because of determinants not associated with the regimen itself but by such factors as presence of alternatives, poor memory and illness explanations. Explanatory models are the way an individual makes sense of an illness or their common sense beliefs about an illness. These beliefs are clustered around identity, cause, time-line, consequences and cure/control. The beliefs influences the types of health-related behaviors and coping mechanism they adopt in dealing with their illness, and it determines the necessity for action including self-care behaviors such as adherence to medication and life style modifications. Studies have shown that patients who perceived their diabetes to be acute and uncontrollable are more likely to have poor adherence. Patients with poor illness coherence who viewed diabetes as a cyclical rather than chronic progressive disease has also been found to have poor adherence and more diabetes related complications [13].At present, there is limited literature on the interaction between explanatory models of diabetes, medication taking behaviors and glycemic control among Nigerians. The purpose of this study was to examine the explanatory models of diabetes among Southwestern Nigerian and how it influences glycemic control in this environment. We hypothesized that health beliefs discordant with the biomedical model of diabetes will be associated with poor medication taking behaviors and glycemic control.

2. Method

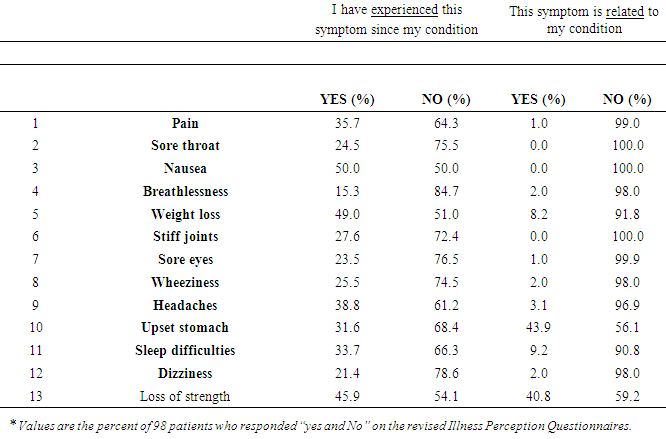

- The study was a hospital based prospective non-experimental study of three months duration among 98 patients with diabetes mellitus on oral hypoglycemic agents at the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. Ethical approval was obtained from the Local Research and Ethics committee prior to commencement of the study. Confidentiality was maintained according to international standard. Patients on oral hypoglycemic agents who visited the Family Medicine Clinic were consecutively was recruited after obtaining an informed consent. Their socio-demographic indices, medication history, explanatory models and medication taking behaviors were assessed. Patients on insulin, those with diabetic emergencies, or on a transit visit were excluded from the study. The following socio-demographic variables were obtained; age, sex, educational status, marital status, employment status. Average monthly fasting blood glucose was used as a surrogate of glycemic control, medication taking behavior was assessed using pill counting and the Illness perception questionnaire-revised edition15 was used to determine explanatory models of diabetes mellitus among this cohort. Illness perception questionnaire is a psychometrically sound tool that has been widely used in studies of illness perception and it provides a quantitative assessment of explanatory models of illness with a good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha’s = .79 to .89) [15]. The illness Perception Questionnaire-Revised edition consists of three parts. Part I is the illness identity, part 2; illness dimension and part 3; causal domain. In the illness identity (part 1); patients were asked if they experienced a specific symptom (based on a total of 13 possible symptoms) and whether they believed the symptom was related to their DM. In part 2; patients were asked to indicate their level of agreement (on a Likert scale, where 1-strongly disagree and 5-strongly agree) with statements concerning an acute/ chronic timeline (2 items about the chronicity of DM), a cyclical timeline (4 items about the cyclical nature of DM), the consequences of DM (4 items about the negative consequences of DM), personal control (2 items representing positive beliefs about personal controllability), treatment control (4 items representing positive beliefs about the treatment ability), illness coherence (2 items about the personal understanding of DM), and emotional representation (5 items about emotions caused by DM). Part 3; the causal domain was presented as a separate section; it consisted of 18 attribution items that were divided into the following 5 sub dimensions: psychological attributions such as personality, stress, or worry (6 items), risk factors attribution such as heredity and smoking (7 items), immunity factors attribution such as germs or viruses (3 items) and accident or chance attribution (2 items). Patients were asked to indicate their level of agreement (on a Likert scale, where 1-strongly disagree and 5-strongly agree) with statements concerning the 5 sub dimensions. At the end of the causal domain, patients are also asked to mention in their own words a maximum of 3 causes for their DM. Patients’ medication taking behavior was assessed using pill counting. Pill count adherence was assessed by asking patients to keep any missed doses in their pill bottle, and pill bottles are checked when medicines are re-filled at the clinic during visits. Adherence was measured as the number of pills taken as a percentage of the number of pills prescribed and dispensed [16].

3. Statistical Analysis

- Categorical variables were reported as percentages and continuous variables as means. Internal consistency of the illness perception questionnaire was calculated for this cohort and Spearman’s rho correlation was used to determine relationship between the explanatory models of diabetes, average fasting blood glucose, and medication taking behaviors. Good adherence was defined as adherence level >80% [17]. A mean fasting Plasma Glucose <130 mg/dl was regarded as a good glycemic control [18]. Chi-square test was used to determine the relationships between medication adherence and socio-demographic characteristics including the illness duration. A Predictive Analytics Software 18 (PASW) was used for statistical analysis. P-value (2 tailed) less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant with a Confidence level = 95%.

4. Result

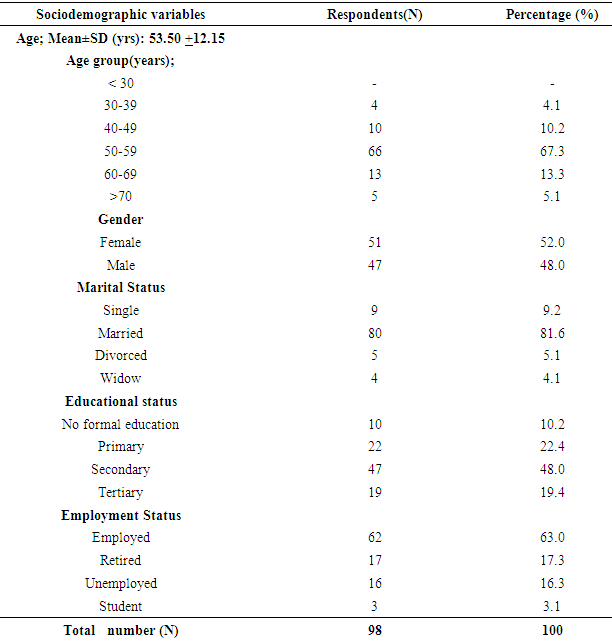

- Clinical characteristics of participants Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the study population. The 98 study participants were all clinic attending patients with type 2 diabetes. Male to female ratio of the cohort was 1:1.1 with most of the participants in their 6th decade of life. The mean fasting blood glucose was 108.2 with 75.5% of the cohort having good glycemic control. Average adherence level was 88.1% with 71.4% of the respondents having good medication taking behavior.

|

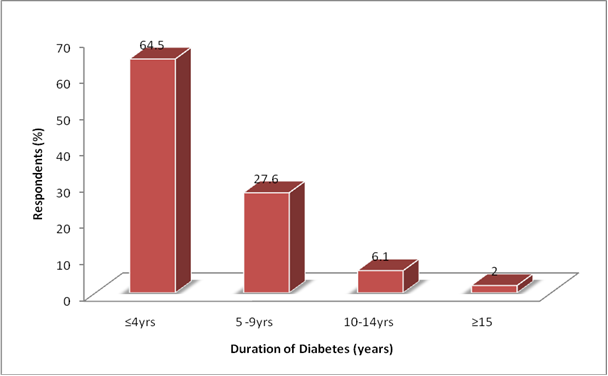

| Figure 1. Duration of illness (years) among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus |

|

|

5. Discussion

- Illness identity:In this study, most respondents experienced nausea, weight loss, and loss of strength and attributed stomach upset and loss of strength to diabetes mellitus. This is in concordance with several studies on perception of diabetes [13, 25-27].In a similar study among the Mexican American’s [25], a variety of symptoms that participants experienced before they were diagnosed with diabetes, ranged from no symptoms to fatigue, weakness, headaches, thirst, increased urination, loss of strength and dry mouth and skin. Some of these symptoms continued after diagnosis. Weight loss and stomach upset were described most frequently as symptoms after diagnosis. Similarly, analysis of the free listings obtained from the interviews of Jamaican diabetic patients [26], yielded several commonly recognized symptoms of diabetes such as weakness or fatigue, nausea, stomach upset, frequent urination, thirst, itching, poor vision, sores that do not heal, hunger, and weight loss. Among the African Americans [26], most participants talked about specific symptoms associated with diabetes such as feeling weak, being easily tired, weight loss and stomach. The more acute symptoms of diabetes such as increased thirst, dry mouth, slow healing, and problems with vision were mentioned less frequently in these studies. However, unlike our study, most of these studies were qualitative studies were participant had opportunity to give a free native of their symptoms.Causal attribution:Items on causal attribution panel most frequently reported were heredity, diet and environmental pollution. Some participants also thought diabetes could be caused by psychological factors such as stress, family worries, or a psychologically traumatic event in the past. This in part agrees with the result of the Mexican American’s explanatory model of type 2 diabetes [25]; where fright, heredity, over work, lack of exercise, diet and generally not taking care of oneself were viewed as contributing factors to the development of type 2 diabetes. Among young Hispanic students [27], genes/heredity, diet and stress featured prominently among their causal narratives. In this study, participants were found to have objective knowledge of their heightened risk for diabetes because of family history. It is thought that having an afflicted first-degree relative is the strongest predictor of a person’s lifetime risk of acquiring the disease and knowledge of one’s objective risk has been found to contribute to individuals’ perceived risk for diabetes [28, 29]. Furthermore, young people today are likely to be exposed to biomedical and scientific explanations of disease through health-related university courses and media outlets where genetic explanations are presented as causal factors in certain diseases [30]. Therefore this factor may represent a combination of objective knowledge of personal risk for diabetes among study participants and greater exposure via academic learning and media exposure to the role of genes and heredity as etiological agents in diabetes. Unlike our study, the Tongan population [13] have predominantly external attribution of causality such as poor medical care in the past, environmental pollution, and God’s will while their European counterpart had an expert models’ causal attribution. Common to most of the studies including our study is the identification of heredity and diet, which emphasizes the perceived significance diet and genetics in etiology of diabetes. Illness Dimensions:Most patients perceived diabetes mellitus to be a chronic illness with serious consequences, and most participants believed that they have good personal and treatment control. They have low scores on emotional representation and timeline cyclical. These findings are consistent with most studies [13, 23, 25-27]. Patients with good knowledge of diabetes are more likely to have good treatment or personal control their illness and are often the least emotionally distressed about their illness. Unlike our study, the Tongan’s population in Australia [13], perceived diabetes as an acute illness with cyclical timeline and they were found to have low confidence in the ability of their action (s) or treatment to control their illness. These patients also attributed their diabetes to external factors with low scores on illness coherence.Association between explanatory models, medication taking behaviors and glycemic controlIn this study, there were no significant correlation between components of the illness explanatory model and educational status, age or gender. However, patients with longer duration of illness viewed diabetes as a disease with serious consequences and were found to be more likely to have understood the course of their illness. The later observation is mostly due to personal experience as one ages with the disease. Accurate knowledge of diabetes, belief in the effectiveness of treatment or personal control diabetes were associated with good medication taking behavior. Similarly, patients who perceived diabetes as a chronic disease with serious consequences were found to be less likely to be distressed about their illness and more likely to adhere to their medication regimen. On the other hand, those who perceived diabetes to be cyclical and caused by external factors such as pollution, poor medical care in the past or chance were less likely to adhere to medication. Patients with poor medication taking behaviors were more likely to have high glycemic profile.These findings are consistent with previous studies on health beliefs, adherence and metabolic control [13, 19-21]. In these studies accurate knowledge of diabetes and the belief in the effectiveness of treatment were found to be predictive of better adjustment to diabetes, medication taking behaviors and metabolic control. Patients with accurate knowledge of diabetes including its complications are more likely to be engaged in Self-care, which is an active and scientific process led by the patient in managing their illness. It is a set of behaviors, which diabetic patients do daily to achieve diabetes control. These behaviors include the regulation of diet, exercise, and medication, self-monitoring of blood sugar (glucose) levels and care of feet. [22]Perception of diabetes as cyclical disease with external causal factors such as pollution, poor medical care in the past or chance may preclude patients from having a sense of personal control over their illness, these patients are less likely to engage in self-care behavior including taking their medications and adhering to life style modification. Additionally, patients with poor self-care behaviors are more likely to develop complications. Several studies have demonstrated a direct correlation between adherence and glycemic control, and patients who do adhere to their treatment recommendations are less likely to have diabetes mellitus related complications. [13, 22-24] Certain limitations were noted in this study; hemoglobin A1c (A1c) is the standard index of metabolic control in diabetes mellitus but in this study, fasting blood glucose was used as the surrogate because behaviors and beliefs are often dynamic and we needed an index of metabolic control that could reflect the subtle changes in these variables. Additionally, at the time of this study, A1c was not readily available and was also very expensive. Pill counting used in this study is objective, simple and cheap. However, it is subject to patient manipulation such as pill dumping. Quantitatively assessing patients’ beliefs often limits their narratives to a set of predetermined outcomes. Finally, although we had adequate sample size to power this study, a larger sample size would have given the study a more objective outlook. Despite these limitations, this is one of the first studies to provide a quantitative assessment of the explanatory models of diabetes mellitus in this environment. Data from this study showed that most of our patients have accurate perceptions of diabetes. This perception makes them more likely to engage in self-management behaviors which include taking medications and adhering to life style modifications. Asking patients about their beliefs may provide medical practitioners with an opportunity to address poor adherence to self-care which often results to poor glycemic control [13]. Explanations can be offered that build on rather than contradict existing beliefs.Studies have shown that interventions that target patients’ illness beliefs are effective in improving self-management behaviors in diabetes [13]. Frontline doctors should be encouraged to take more interest in patients’ health beliefs and factors that influences them in order to optimize glycemic control. This study has identified perception domains with the greatest association with medication taking behaviors and glycemic control in this environment. Future studies should focus on interventions that improve these perception domains with the view of optimizing adherence and glycemic control.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML