-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Diabetes Research

p-ISSN: 2163-1638 e-ISSN: 2163-1646

2015; 4(1): 7-12

doi:10.5923/j.diabetes.20150401.02

Type 2 Diabetes: Challenges to Health Care System of Pakistan

Rashid M Ansari , John B Dixon , Jan Coles

School of Primary Health Care, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Correspondence to: Rashid M Ansari , School of Primary Health Care, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This review article is aimed at describing the epidemic of type 2 diabetes in Pakistan and focusing particularly on the middle-aged population of Pakistan. Type 2 diabetes is a major public health problem in Pakistan as the middle-aged population in that country is overweight or obese, lack of physical activity, unhealthy food and eating habits exposing this population to a high risk of type 2 diabetes. This article provides insight into the health care system of Pakistan and compares its performance using the criteria set up in the world health report. The country ranked 133rd on the overall health system attainment and ranked 7th in the world on diabetes prevalence. A variety of factors have been identified in this article as the leading cause of low ranking of health care system such as poor utilization of primary health care services, lack of physical accessibility to health system, inadequate health system to manage diabetes, gender disparity and inequity in the health care system. The primary objective of this study is to improve the understanding of self-management of diabetes among the middle-aged population of Pakistan and to identify the barriers to self-management of diabetes and quality of life in that region.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, Self-Management, Epidemiology, Pakistan, Health care system

Cite this paper: Rashid M Ansari , John B Dixon , Jan Coles , Type 2 Diabetes: Challenges to Health Care System of Pakistan, International Journal of Diabetes Research, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2015, pp. 7-12. doi: 10.5923/j.diabetes.20150401.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- This article gives an overview of epidemiology of type 2 diabetes looking into the public health problems caused by “Diabetes Mellitus” globally and locally among the middle-aged population of Pakistan. The patients in Pakistan with type 2 diabetes require great care and self-management education and understanding of this disease. The country is facing the greatest challenges for its healthcare system in managing the chronic diseases where diabetes is considered a "self-inflicted" disease and there is stigma attached to this disease in the society. The stigma of being “sick person” also affects the diabetic person all his life as a result of being seen as “different” by his colleagues, friends, teachers and community members in all the stages of life cycle.It is generally agreed that self-management is required for control of chronic diseases and for prevention of disease complications; however, patients generally do not adhere to self-management recommendations [1-3]. The adherence to the recommendations and barriers are both problematic for “lifestyle” behaviour such as eating patterns and physical activity rather than medication adherence [4-6]. This is evident from the culture, tradition and life style behaviour of the people of Pakistan that both the eating patterns and physical activity are posing a great deal of difficulties to middle-aged population in the self-management of their diabetes. It has been pointed out by Marzilli [7], that eating behaviours of others can influence eating behaviours of diabetic patients, especially if they live together; which is the case in Pakistani society where there is a joint family living system. Ecological perspectives also point to the importance of access to key resources in self-management [8]. Healthy eating patterns and physical activity levels are not likely to occur or persist without convenient sources of healthy foods and attractive safe settings. There is a growing interest on the impact of “built environment” on physical activity in recent years [9, 10]. For example, studies have demonstrated the strong negative and positive effects that access to resources for physical activity [11, 12] and consumption of food purchased away from home [13] have on overweight and obesity.

2. The Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes

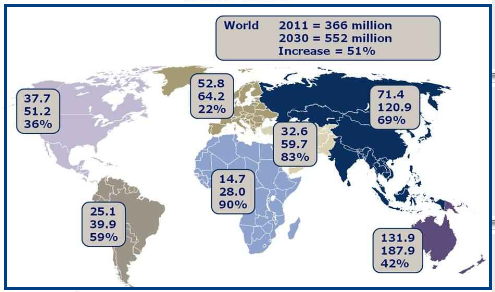

- Diabetes mellitus is a pandemic disease and is one of the main threats to human health [14]. In the recent estimate of International Diabetes Foundation (IDF), it was mentioned that worldwide there were 366 million people with diabetes in 2011 and 371 million people with diabetes in 2012, with China (92.3 million), India (63 million) and the United States (24.1 million) leading the way and 4.8 million people died due to diabetes and also 4 out 5 people with diabetes live in low and middle income countries [15, 16]. The greatest number of people with diabetes is between 40 to 59 years of age and diabetes caused more than 471 billion dollars to spend on healthcare globally. The prevalence of diabetes in the world is 8.3%, in Saudi Arabia, 23.4%, in Pakistan, 7.89% and in Australia the prevalence of diabetes has reached to 9.55% [16]. The Figure 1 presents the global projection for the diabetes epidemic from 2011-2030.

| Figure 1. Global projection for diabetes epidemic: 2011-2030: source [16] |

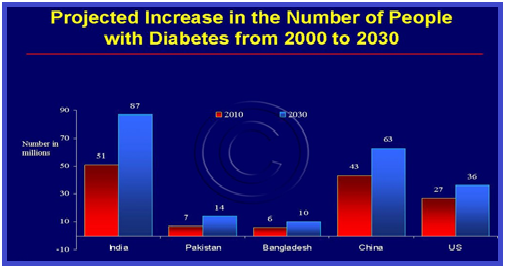

| Figure 2. Prevalence of diabetes in Pakistan by 2030: Shaw et al [20] |

3. Characteristics of Type 2 Diabetes

- Type 2 diabetes is associated with certain ethnic groups, obesity, family history of diabetes, and physical inactivity, among other factors. Diabetes is a metabolic disease characterized by elevated concentrations of blood glucose for prolonged periods of time, i.e., hyperglycemia [26]. Chronic, untreated hyperglycemia can lead to serious complications that include cardiovascular diseases, blindness, kidney failure, and stroke. Furthermore, very low values of blood glucose (hypoglycemia) for even a short duration can result in loss of consciousness and coma. The type 2 diabetes is a syndrome characterized by insulin deficiency, insulin resistance, and increased hepatic glucose production. These metabolic abnormalities are treated by use of various medications which are designed to correct one or more of metabolic abnormalities [27]. The complications of type 2 diabetes from microvascular and macrovascular diseases can have a devastating effect on quality of life and impose a heavy burden on healthcare systems.The primary objective of this study is to improve the understanding of self-management of diabetes among the middle-aged population of Pakistan and to identify the barriers to self-management of diabetes and quality of life in that region. This study will also contribute to improving the quality health care for diabetes in health clinics in that region and would recommend a multifactorial approach emphasizing patient education, culturally-tailored diabetes self-management intervention, improved training in behavioural change for providers, and enhanced delivery system. The understanding of people about diabetes and susceptibility to diabetes is linked to family, community and society and therefore, this study will impress upon the need to recognize that in developing strategies and interventions to address diabetes, self-care, family support, community education and community ownership are important.

4. Health Care System of Pakistan

4.1. Background Information

- The health care system of Pakistan has been confronted with problems of inequity, scarcity of resources, inefficient and untrained human resources, gender insensitivity and structural mismanagement. With the precarious health status of the people and poor indicators of health in the region, health care reforms were finally launched by the government in 2001. The Government of Pakistan spends about 0.8% of GDP on health care, which is lower than some neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh (1.2%) and Sri Lanka (1.4%) [28]. In Pakistan, only 3.1% of the total annual budget is allocated for economic, social and community services, and 43% is spent on debt servicing [29]. In most of the developing countries of South Asia, out-of-pocket household expenditure on health is at times as much as 80% of medical expenditure [30]. For health expenditure in Pakistan, it is about US$ 17 per head per year, out of which $13 is out-of-pocket private expenditure [31]. The country spends 80% of its health budget on tertiary care services, which are utilized by only 15% of the population. In contrast, only 15% is spent on primary health care services, used by 80% of the population [32].

4.2. Pakistan Health Statistics

- The World Health Organization (WHO) ranked Pakistan 122nd in overall health system performance among 191 countries [33]. The health indicators, health funding, and health and sanitation infrastructure are generally poor in Pakistan, particularly in rural areas. About 19 percent of the population is malnourished of which 30 percent of children under age five are malnourished. The leading causes of sickness and death include gastroenteritis, respiratory infections, diabetes, congenital abnormalities, tuberculosis, malaria, and typhoid fever. The United Nations estimated that in 2003 Pakistan's HIV prevalence rate was 0.1 percent among 15–49, with an estimated 4,900 deaths from AIDS. Hepatitis B and C are also rampant with approximately 3 million cases of each in the country at the moment. The burden of disease due to communicable and non-communicable disease is 52.8% and 39.4% respectively with total DALY’s 56.1 % and 34.2% [34]. According to official data, there are 127,859 doctors and 12,804 health facilities in the country to cater for over 170 million people [35]. In 2007 there were 85 physicians for every 100,000 persons in Pakistan that is one doctor for 1,225 people. According to the Ministry of Health Pakistan statistics, there were 13,937 health institutions in the country including 945 hospitals (with a total of 103,285 hospital beds), 4,755 dispensaries, 5,349 basic health units (mostly in rural areas), 903 mother and child care centers, 562 rural health centers and 290 TB centers [36, 37]. There is an inequitable distribution of GP’s in the country, with 70% practicing in urban areas where only 30% of the population lives: in addition, only 10% to 15% of GP’s in rural areas are females.

5. Challenges to Health Care System

5.1. Self-Management Approach

- Despite the high prevalence of diabetes and serious long term complications, there is still a lack of established evidence-based guidelines for self-management [38] and translation of practice recommendations to care in Asian countries [39] and as well as in developed countries [40]. Therefore, there is a need of self-management approaches for patients with type 2 diabetes and the assessment of quality of diabetes care in the community can help draw attention to the need for improving diabetes self-management and provide a benchmark for monitoring changes over time. One of the studies conducted in Pakistan on diabetes knowledge, beliefs and practices among people with diabetes [41] provided further evidence that there was a lack of information available to people with diabetes in Pakistan as the large population has never received any diabetes education at all [41]. Also, the study was conducted in an urban university hospital, where diabetes education may be more readily available as compared to rural areas where people have less access to information and will have even poorer diabetes perception and practices. The other studies carried out in Pakistan on diabetes education and awareness suggest that level of awareness at both physicians and patients along with other community people has been observed to be low [42-49].Fisher et al. [50] suggested that the quality clinical care and self-management are compatible and dependent on each other and without sound care, patient’s efforts may be misdirected and expert clinical care will fall far short of its potential, through patient failure to use prescribed medications to control his/her blood sugar or to implement its management plans [50]. A framework for integrating the resources and support for self-management with key components of clinical care was also provided by Wagner et al. [51] in their chronic care model. A number of studies have also suggested that patient understanding and beliefs about health and illness may be shaped by historical and local contexts [52], whether respondents are thinking about health or behaviour in general or about their own [53], and personal experience and observation [54].

5.2. Health Services in the Local Community

- The health services in the community in Pakistan are not adequate and diabetes health management programme in the community health clinics does not provide enough help and support to the patients. Shortage of community doctors and expensive consultation with private doctors make the life of patients more difficult in terms of managing their diabetes in that region of Pakistan. The chronic disease care is mostly integrated into the public health system through primary health care. Usually, people with diabetes are referred from primary health-care clinics to specialist diabetes centers. There are two reasons for this approach. The first reason is that the health care interventions to manage diabetes cases starts with the registration of the patient in a primary health care clinics and the issuing of diabetes card. Medical diagnosis includes a physical examination and laboratory studies.These clinics in Pakistan face special challenges to provide diabetes care to the poor patients as most of these clinics do not meet the evidence-based quality of care standards as compared to the targets established by the American Diabetes Association [55].

5.3. Structure of Primary Care Services Delivery

- In Pakistan, basic health units are seeing an average of 20-25 patients per day where each basic unit has about 10 staff members. The primary care delivery system and satisfaction level have largely remained unchanged during the last three decades. The recent surveys indicate that nationally, not more than 20% of the people used the first level public sector network for their health care needs [29, 36]. Therefore, the economic constraints, lack of good governance and inability to deliver public goods have led to the concept of “unleashing the primary care to contracting services in Pakistan” [56-58]. This primary care contracting was initially implemented in one of the cities in Pakistan and received good results, the situation in the city was improved in terms of utilization of basic health services, community satisfaction, out of pocket expenditure and quality of care. This contracting of primary health care service has been extended to several cities and the provinces and is a major change in public sector health system especially for the people living in rural area of Pakistan.

6. Barriers to Diabetes Care

- Glasgow et al. [59] have identified two types of barriers (internal and external) psychosocial and cultural barriers to diabetes care (self-management) and quality of life. Psychosocial barrier is related to interpersonal factors that impede diabetes self-management and the other external barrier is related to biological factor such as organization of medical care and community and cultural influences [59].The psychosocial barriers influence longer-term outcomes, such as glycemic control (HbA1c) and eventually development of diabetes complications. The middle-aged population of Pakistan have both psychosocial and cultural barriers to their diabetes management and literature review reveals non-compliance on eating patterns, lack of physical activity, lack of family and cultural support and difficulties in accessing medical care [41-49]. There is evidence to support this analysis from the review which was in agreement with Brown and Hedges [60] that psychosocial barriers such as stress, depression, low level of efficacy, lack of social and community support may have direct as well as indirect effects on metabolic outcome. Therefore, lack of social support, particularly from friends and family is also considered a barrier to dietary adherence and self-management [59].

7. Conclusions

- This has been demonstrated in this review article that Pakistan health care system is inefficient and in order to improve its ranking in the world, it requires rational policies to provide efficient, effective, acceptable, cost effective, affordable and accessible services to its population. The healthcare system performance measurement and management frameworks still need to address some conceptual issues concerning effectiveness and quality on the basis of the criteria suggested by World Health Organization and translate the research into policy and action and that will have an impact on the direction or implementation of currently launched health reforms in Pakistan.This study will be useful for health care professionals suggesting that coping with diagnosis and living with diabetes is affected by a complex constellation of factors, including life circumstances, social support, gender roles and economy. Consequently, this study will enhance the knowledge and understanding of patients of diabetes with regards to self-management of this chronic disease and will improve the health care system of Pakistan in managing and treating the patients with chronic disease.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML