-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Diabetes Research

p-ISSN: 2163-1638 e-ISSN: 2163-1646

2014; 3(5): 71-77

doi:10.5923/j.diabetes.20140305.01

The Opinion of Practice Nurses and Dietitians on Implementing Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME) in Africa and the Caribbean

Chidum E. Ezenwaka1, Clementina U. Nwankwo2, Philip C. Onuoha1, Nneka R. Agbakoba2

1Faculty of Medical Sciences, The University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus, Trinidad, Tobago

2Faculty of Health Sciences & Technology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Chidum E. Ezenwaka, Faculty of Medical Sciences, The University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus, Trinidad, Tobago.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Several reports have shown that diabetes self-management education (DSME) assists in preventing diabetes complications. This study assessed the opinions of practice nurses and dietitians on implementing DSME in Africa and the Caribbean. A total of 1,574 practice nurses and dietitians (1,057 Caribbean, 517 Nigerians) employed in the Ministries of Health in the two populations completed the self-administered research questionnaire previously pre-tested on a cohort of student nurses. The study was conducted in 2014 and 2012 in Nigeria and Trinidad & Tobago respectively. One research assistant was engaged for each study site to facilitate the distribution and collection of completed questionnaires from the volunteers. The anonymous questionnaires were distributed to nurses and dietitians in public hospitals and health centres in the two study populations. The majority of all the 1574 participants agreed that intensification of DSME is a good idea that will be helpful to the patients (94.5%) and assist to reduce long-term diabetes complications (89.7%). However,remarkable proportions of all participants agreed that their establishments do not have enough qualified health personnel (68.4%), educational facilities (63.6%) and economic resources (61.3%) for DSME. In all, only 29% of all participants believe that their work places were prepared to implement DSME. The expressions of inadequate qualified healthcare personnel, economic resources and educational facilities for DSME in these two populations constitute significant barriers to implementing effective DSME and may well reflect the situation in the remaining developing countries. Healthcare professionals working in the developing countries should intensify lobbying towards government’s investment in human and material resources for DSME.

Keywords: Diabetes self-management, Diabetes complications, Diabetes education, Developing countries

Cite this paper: Chidum E. Ezenwaka, Clementina U. Nwankwo, Philip C. Onuoha, Nneka R. Agbakoba, The Opinion of Practice Nurses and Dietitians on Implementing Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME) in Africa and the Caribbean, International Journal of Diabetes Research, Vol. 3 No. 5, 2014, pp. 71-77. doi: 10.5923/j.diabetes.20140305.01.

1. Introduction

- The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) current diabetes atlas Report on the global prevalence rates of diabetes showed that 382 million people are currently living with diabetes with higher prevalence rates in low and middle-income countries of the world [1]. The new global projection showed that more than 592 million people will be living with diabetes in 2035 given that as many as 175 million people are currently undiagnosed [1]. As new data becomes available from developing countries such as China, the Middle East and Africa the prevalence rates in developing countries increase even above the previous report [2]. Although there is escalation in the prevalence rates of diabetes in the developing countries, it should be admitted that there has been significant regional and international campaign initiatives towards preventing diabetes in low-income regions of the world [3-5]. Despite these regional and international efforts [3-5], it has been reported that about four million diabetes-related deaths take place every year, and 80% of this is in the developing countries [6]. Therefore it is important to focus on preventing diabetes complications in poor countries through diabetes self-management education (DSME) in addition to using therapeutic measures. Mortality estimates attributable to diabetes show a high prevalence of diabetes-related deaths in developing countries [6], and yet these poor countries usually have low budgetary allocations to the Ministries of Health. In India, for example, the national budgetary allocation for healthcare in 2010 was US$4.5 billion whereas the estimated annual direct and indirect costs for diabetes care in the same year was US$31.9 billion [7]. Furthermore, current IDF diabetes atlas report shows that health expenditure on diabetes in South-East Asia and Africa accounted for less than 1% of all global health expenditure on the disease [1].The limited economic resources in developing countries demands that appropriate educational initiatives aimed at educating the patients and the healthcare providers on DSME maybe a far reaching solution in preventing diabetes complications in developing countries. Many studies have shown that non-pharmacological educational intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes were effective in preventing diabetes complications especially when using optimized tools [8-12]. Additionally, other studies in the developed countries have confirmed that non-pharmacological interventions assisted in controlling glycemia in type 2 diabetes patients and subsequently prevent diabetes complications [13-15]. Although diabetes patients, especially those in the less privileged populations, do not usually get a satisfactory assistance or encouragement for diabetes self-care [16], a culturally competent diabetes self-management education (DSME) has been demonstrated to assist in reducing blood glycemia and improve the patients’ diabetes knowledge score [17]. Therefore, given that nurses are usually involved in the promotion of diabetes self-care [18], efforts at promoting DSME in the developing countries would be more effective if the healthcare providers (especially the practice nurses and dietitians) in different cultural and ethnic populations are fully involved. Thus, the present study was aimed to determine the opinion of practice nurses and dietitians on DSME and the preparedness of their work establishments in implementing diabetes self-care in Africa and the Caribbean.

2. Methods

- Recruitment of subjects in Trinidad and Tobago: The survey was conducted in the whole country. The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago is a population of 1.3 million people and has a land mass of 5,128 square kilometre and an average population density of 262.45 people per square kilometre of the land area [19]. It is estimated that there are 1,498 practice nurses and dietitians employed in the five regional health authorities during the time of the study in 2012 and all were targeted for the study. The study was conducted between November 2011 and April 2012. At the end of the study, 1,032 Registered Nurses (RN) and 25 Registered Dietitians (RD) participated in the survey; representing about 71% of the estimated 1,498 practice nurses and dietitians employed in the five regional health authorities. Recruitment of subjects in Nigeria: The study was conducted in Anambra state in the Federal Republic of Nigeria, located in the South-eastern part of the country. Anambra State has a population of 4.2 million people and a landmass of 4,844 square kilometre with estimated population density of between 1,500 and 2,000 persons per square kilometre of the land area [20]. Anambra State compares well with the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago in terms of land mass but has higher population density and total population figure. There are 507 Health Centres, 33 General Hospitals and two University Teaching Hospitals in the state. The Ministry of Health had about 550 registered nurses on record at the time of the study excluding practice nurses that were not under the Ministry. The research questionnaires were distributed to all practice nurses and dietitians at the Health Centres, General Hospitals and Teaching Hospitals. The study was conducted between May and August 2014. At the end of the study, 516 nurses and 29 dietitians participated in the survey; representing about 93.8% of the estimated 550 Nurses registered with the Ministry of Health in Anambra state. For the two populations, a total of 1,602 nurses and dietitians in Nigeria and Trinidad and Tobago volunteered and participated in the studies. Study Protocol: The study protocol for the two study sites were the same and has been published previously (21). Briefly, the research questionnaire consists of four sections: (i) Bio-data and human resource with six closed-ended item questions, (ii) nurses and dietitians continuing medical education with eight open- and closed-ended questions, (iii) views of nurses and dietitians on DSME with five closed-ended questions, and (iv) views of nurses and dietitians on barriers to diabetes education with six closed-ended questions (21). Since the nurses and dietitians were educated and capable of understanding the health-related questions, a self-administered research questionnaire was designed and was pre-tested on a cohort of student nurses who were studying for upgrade course to bachelor’s degrees. To preserve the anonymity of the participants, the questionnaires did not contain any personal identifiers. Thus, during the study on both sites, the research questionnaires with the explanatory letters and consent forms were distributed to all public hospitals and health centres as identified above. Thus after reading our letter of explanation of the aims and purpose of the study, nurses and dietitians that consented to participate in the study completed the questionnaires and returned them to the respective research assistants in each country of the study (21). The Institutional Ethics Review Committees at both sites approved the study protocol. Statistics: The statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) was used for the statistical analysis. Of the 1,602 participants, the data of 28 subjects were excluded from analysis because of non-completion of sections III and IV of the research questionnaire. The views of the remaining 1,574 participants on DSME from the two sites were compared using chi-squared (X2) test for non-parametric parameters. The data were presented as absolute number and percentages (in parenthesis). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

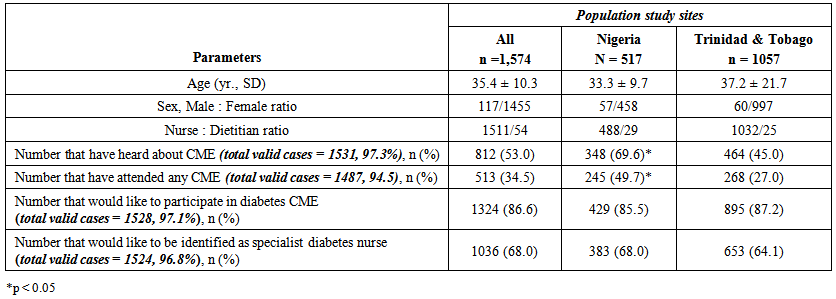

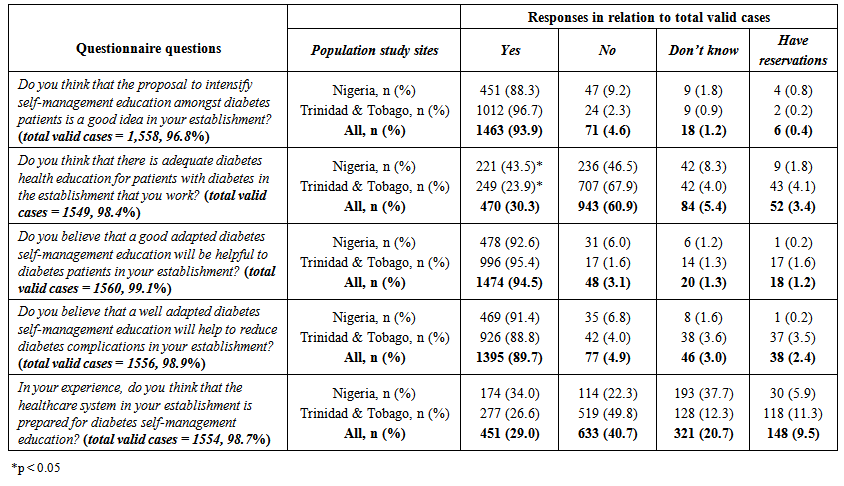

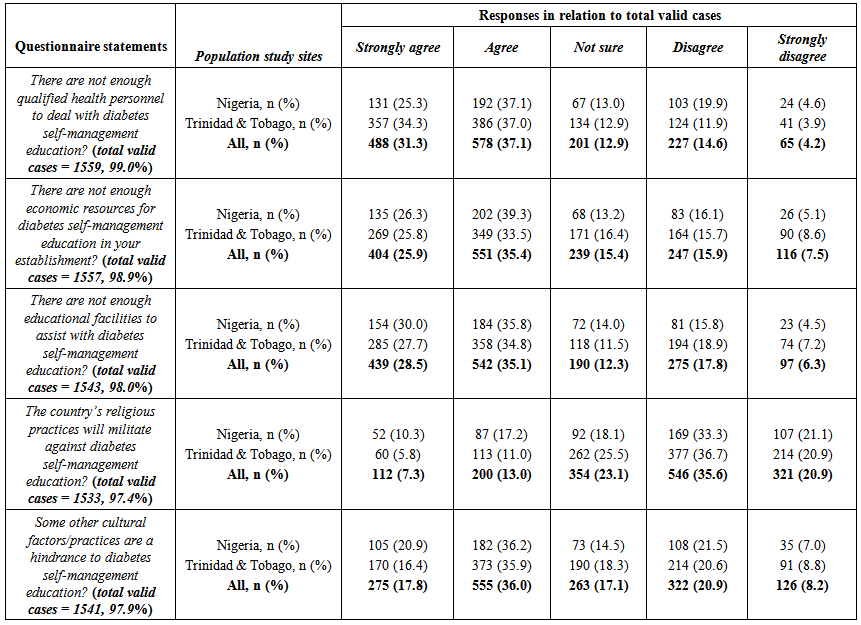

- Table 1 shows the background information of the practice nurses and dietitians from Nigeria and Trinidad and Tobago. The data of 1,574 participants (1,520 nurses and 54 dietitians) were analysed and included in this report. Table 1 shows that equal percentages of participants from the two countries would like to participate in diabetes continuing medical education (85.5% vs. 87.2%) or specialise as diabetes nurses (68.0 vs. 64.1, p > 0.05). However, a comparatively higher percentage of Nigerian participants have heard (69.6% vs. 45.0%) or attended (49.7% vs. 27.0%) any continuing medical education (all p < 0.05). The views of the participants on diabetes self-management education (DSME) are shown on Table 2. About 94% of all the study participants agreed that intensification of DSME amongst diabetes patients is a good idea for their establishments. There is a significant difference in opinion regarding patients’ health education in the two populations. While 24% of Trinidad and Tobago participants thought that there is adequate diabetes health education for their patients, a comparatively higher percent of Nigerian participants shared a similar opinion (24% vs. 44%, p < 0.05). However, the nurses and dietitians from the two populations agreed overwhelmingly that a good adapted DSME will be helpful to the patients (94.5%) and also assist to reduce diabetes complications (89.7%). Interestingly, only 34% of Nigerian and 26.6% of Caribbean participants (overall 29%) believed that their work places were prepared to implement DSME (Table 2). Table 3 shows the views of the participants on the preparedness of the healthcare system in their population for DSME. Overall the majority (strongly agree and/or agree) of all the participants from the two populations agreed that there were not enough qualified health personnel (68.4%), educational facilities (63.6%) and economic resources (61.3%) for DSME in their places of work (Table 3). While 53.6% of all the participants agreed that some cultural factors or practices could be a hindrance to DSME, 56.5% do not agree that religious practices will be a barrier against DSME in their populations (Table 3).

| Table 1. Background information of the Nurses and Dieticians interviewed in the two populations |

| Table 2. The views of Nurses and Dieticians on diabetes self-management education in the two populations |

| Table 3. The views of Nurses and Dieticians on the preparedness of healthcare system for diabetes self-management education in the two populations |

4. Discussion

- Practice nurses and dietitians in two developing countries in Africa and the Caribbean were interviewed on diabetes self-management education (DSME) and the preparedness of their respective healthcare institutions on implementing DSME. The analysis of our data showed remarkable similarity in opinion between Nigerian and Caribbean participants. Irrespective of country of practice, the nurses and the dietitians agreed that (i) diabetes self-management education would assist to reduce diabetes complications, (ii) there were not enough qualified health personnel, educational facilities, economic resources in their places of work, and (iii) there were cultural factors or practices that are hindrances to diabetes self-care education in both populations. These findings are discussed in relation to the call for intensified DSME in the developing countries [22], and the need to overcome the challenges of implementing DSME in countries with limited economic resources [23, 24]. The finding that the practice nurses and dietitians from both countries agreed that diabetes self-management education would assist to reduce diabetes complications is not surprising. Practice nurses and dietitians ought to have the theoretical knowledge of the benefits of DSME and it is well known that practice nurses are usually involved in individualized patients management and other health promotion activities [18]. Thus, the opinion expressed by these health professionals from two different countries in the developing regions of the world supports the fact that DSME should be an important health policy in every population. However, while self-management education for patients living with chronic diseases is an integral part of patient’s management plan in more developed countries, absence of health educational activities is a major challenge in many developing countries [23]. For instance, in our experience, most clinics in the two populations studied had non-specialist nurse educators conduct generalized diabetes health education in a non-structured format within a short time frame of the usually crowded chronic disease clinics. The clinic education class is not usually tailored to meet individual patient’s needs/challenges or set goals for lifestyle modifications or made provision for feedback from the patients in the next clinic [21]. This anecdotal experience from these two populations in developing countries would suggest that the practice of diabetes self-care is sub-standard in these populations and might reflect the situation in the remaining developing regions of the world. Such a standard can hardly meet the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) bench mark for diabetes health education [25] and effective DSME [25, 26]. Interestingly, the IDF in a position statement on self- management education has reinforced the importance of both DSME and diabetes self-management support (DSMS) in preparing diabetes patients in making well informed decision, coping with the challenges of living with diabetes and assisting in lifestyle modifications that support the patient’s self-management efforts [27]. In spite of the advisory position statement of IDF [27], patients attending clinics in developing countries have been shown to have low records of dietary or exercise advice [28]. Consistent with the previous report [21, 23], our findings in the present study showed that only 30% of all the nurses and dietitians think that there was adequate diabetes health education in their places of work (Table 2). Thirty percent (30%) favorable opinion on diabetes health education for the two populations is certainly poor and needs urgent strategic intervention. Although World Bank classified Trinidad and Tobago and Nigeria as high-income and low-middle income economies respectively [29], the practice nurses and dieticians from both populations agreed that there were not enough qualified healthcare personnel, educational facilities and economic resources in their work places to facilitate DSME as previously reported in Trinidad and Tobago [21]. Thus, diabetes self-management could only be effective when there is expert clinical care that is delivered in a multidisciplinary format to a motivated and well-supported patient [30]. Thus for a diabetes patient to acquire the necessary skill to start self-care practice, such a patient should have access to adequate diabetes health education and training as provided by a multidisciplinary healthcare team. However, in this study, we found a significantly low ratios of dietitians to nurses in the two populations studied. This apparent shortage of important healthcare professionals in the area of nutrition and dietetics may affect healthcare delivery in a multidisciplinary fashion as previously suggested [30]. Indeed, we had previously demonstrated that, under appropriate supervision, motivated and well-supported type 2 diabetes patients practiced self-care and had improved blood glycaemia and reduced coronary heart disease risk profile [31]. These two healthcare professionals (nurses and dietitians) have unequivocally expressed the view that the health care system in both populations were not prepared for DSME; similar to our previous report in Trinidad and Tobago [21]. These views may be attributed to the usual disproportionate budgetary financial allocation to the healthcare sector in many developing countries [7]. The current IDF diabetes atlas report showed that while China and India have the highest number of people currently living with diabetes (163.5 million), more money was spent on healthcare for diabetes in North America and Caribbean than any other region of the world [1]. Therefore, for effective DSME to take place, it is important for governments of the developing countries to allocate adequate economic resources to the public health sector. It is believed that this will assist to address issues of diabetes patients within the low-income group who often suffer from diabetes complications because of the health inequalities for persons with financial barriers and lack of personal health insurance policies [32]. Our study showed that more than one half of all the participants agreed that there were cultural factors or practices that could constitute barriers to effective DSME in their populations. This observation warrants further investigation given that the design of the present study did not require the participants to enumerate such factors or practices. Thus, we are left to speculate that the cultural factors that could potentially influence effective DSME in both populations would be similar to those already reported from the developing countries [33-35]. In our experience in both populations, factors that pose major challenges include the patients’ willingness to accept that: diabetes is a chronic disorder that cannot be cured, attending diabetes education classes is part of the diabetes management plan, and lifestyle behavior modification is a key factor for self-management. We suggest that workers in the developing countries should conduct studies to identify specific cultural practices that could influence effective DSME in each population. One interesting experience we have had in the Caribbean population is the patient’s reluctance to translate their theoretical knowledge into practical use. For instance, Caribbean type 2 diabetes patients have high theoretical knowledge score on the benefits of healthy lifestyle [35], yet there are reports of high prevalence rates of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome [37]. Although the nurses and dietitians practicing in Africa and Caribbean agreed that DSME will assist to reduce diabetes complications in the developing countries, the identification of inadequate qualified healthcare personnel, economic resources and educational facilities for DSME in these two populations constitute significant barriers to implementing DSME and may well reflect the situation in the remaining developing countries. We recommend that healthcare professionals working in the developing countries should continue to lobby their governments into investing human and material resources for DSME to assist in reducing long-term diabetes complications. There are limitations to the study. First, the nurses and dietitians were not provided with a definition of the concepts of DSME program for the assessment. However, we are inclined to believe that the participants had an understanding of the basic concepts of DSME as professionals. Again, although all the nurses and dietitians were certified registered nurses and dietitians, we did not ascertain the number of participants that had higher educational qualifications. It is possible that subjects’ opinion might be related to educational background.

5. Conclusions

- The expressions of inadequate qualified healthcare personnel, economic resources and educational facilities for DSME in these two populations constitute significant barriers to implementing effective DSME and may well reflect what is obtainable in the remaining developing countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study was supported by the Publication and Research Fund from the University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus and the Faculty of Health Sciences and Technology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nigeria. We thank the two Research Assistants (Ms Elizabeth Martins for Trinidad and Tobago and Ms Chioma Linda for Nigeria) for their assistance in the distribution and collection of the research questionnaires. We appreciate the cooperation of the relevant Health Authorities in both countries.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML