-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Practice

p-ISSN: 2326-1463 e-ISSN: 2326-1471

2019; 8(1): 10-15

doi:10.5923/j.cp.20190801.02

Functional Polymorphism of Coagulation Factor II Gene in Patients with Systematic Lupus Erythematosus and Its Correlation with Cardiovascular Events

Fatmaa El Zahraa Diab1, Seham Bahgat1, Khalida El Refaei2, Dina Badway1

1Department of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University for Girls, Cairo, Egypt

2Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University for Girls, Cairo, Egypt

Correspondence to: Dina Badway, Department of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University for Girls, Cairo, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

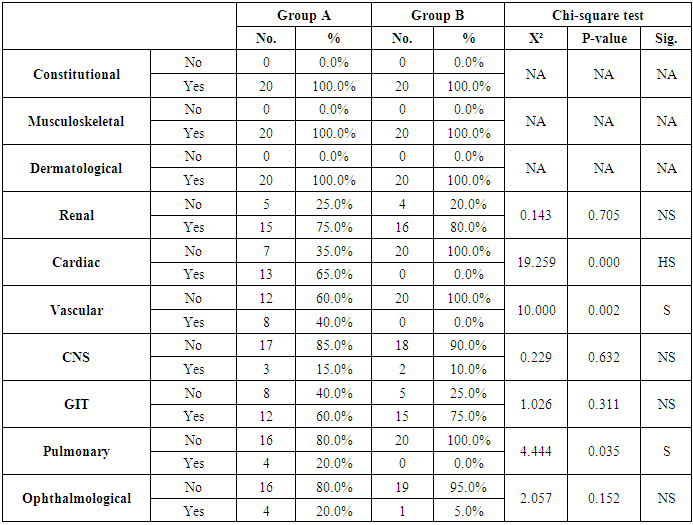

Aim: To investigate the possible association of FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A) and cardiovascular events risk in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). Methods: The present study was carried out on 40 patients with SLE selected from Al-Zahraa University Hospital in the period from April 2014 to April 2016. The FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A) was measured by Real Time-Polymerase chain Reaction (RT-PCR). Results: The present study included 40 patients with SLE and 20 normal controls. There was non-significant difference as regard G20210A mutation in patients with SLE and normal controls. Similarly, there was non-significant difference as regard G20210A mutation in patients with cardiac complications in compared to patients without cardiac complications. When we compared the patients with and without history of cardiovascular complications, there were highly significant increase in patients with cardia complications regarding cardiac symptoms (P<0.001), vascular, and Pulmonary symptoms (P=0.002 and 0.035, respectively). Conclusion: In conclusion, SLE patients with G20210A mutation are not at increased risk of cardiovascular events.

Keywords: Systematic Lupus, G20210A mutation, Cardiovascular events

Cite this paper: Fatmaa El Zahraa Diab, Seham Bahgat, Khalida El Refaei, Dina Badway, Functional Polymorphism of Coagulation Factor II Gene in Patients with Systematic Lupus Erythematosus and Its Correlation with Cardiovascular Events, Clinical Practice, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 10-15. doi: 10.5923/j.cp.20190801.02.

1. Introduction

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is one of the main public health burdens with significant contribution to the global morbidity and mortality. It is a progressive, chronic, disorder that affects multiple systems with recurrent episodes of exacerbations and remissions [1]. According to recent epidemiological figures, the estimated global incidences of SLE ranges from 0.3 – 23.2 per 100 000 person-years, with highest incidence in North America [2]. Although the exact pathogenesis of SLE is still unclear, it is widely believed that the disease arises as a result of abnormal autoimmune process; patients with SLE were found to have defective clearance of apoptotic cells with subsequent development of auto-antigens and deregulated immune responses (affecting both innate and adaptive immunity) [3,4]. Various environmental and hormonal factors were linked to increased risk of SLE in genetically susceptible individuals [5]. SLE is characterized by wide range of clinical manifestations that mainly affects women in their reproductive age, patients with SLE often present with fatigue, weight loss, myalgia and muscle weakness, recurrent infection, and migratory polyarthropathy [6]. Moreover, a considerable proportion of the patients present with multiple systems affection such as lupus nephritis, pericardial disorders, valvular abnormalities, and cognitive dysfunction [7]. Despite that the recent advances in diagnosis and treatment in SLE have led to excellent survival rates, SLE is still associated with high rate of complications, hospitalization, and impaired daily activities [4].Co-morbidities of cardiovascular system are one the most devastating complications of SLE. According to previous reports, cardiovascular complications are present in almost half of lupus patients and it can affect all cardiac structures [8]. The current body of evidence shows that SLE patients are at increased risks of accelerated atherosclerosis, coronary heart diseases, myocardial infarction, stroke, and other thrombotic events [9]. Despite the exact pathogenesis of cardiovascular complications in SLE is not fully understood, various mechanisms have been proposed such as elevated lipid profile, endothelial dysfunction, and circulating autoantibodies [10,11]. Coagulation abnormalities are other risk factors for cardiovascular complications in SLE, previous reports showed that patients with SLE had significantly higher prothrombin level than normal population [12]. It is well known that elevated prothrombin level is associated with significant increase in risks of thrombosis, especially in SLE patients whom autoantibodies bind with prothrombin and trigger inflammatory vascular cascades [13].Recently, a growing body of evidence suggested that single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene encoding prothrombin may predict a significant burden of cardiovascular comorbidities in SLE patients [14]. However, -to our knowledge- only few studies assessed the role of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene encoding prothrombin. Therefore, we performed this study to investigate the possible association of FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A) and cardiovascular events risk in SLE.

2. Patients and Methods

- The protocol of the present study was registered by the local ethics committee of Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University for Girls. Written informed consents were obtained from all patients prior to study’s enrollment. Study Design and Patients:The present study was a case-control study that was carried out on patients with SLE who were selected from Al-Zahraa University Hospital in the period from April 2014 to April 2016. The study included 40 patients who were diagnosed with SLE and 20 age and sex-matched healthy controls. Adults, female, patients (aged > 18 years old) with diagnosis of SLE according to the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria were included [15]. The patients group was further subdivided according to the presence of history of cardiovascular events. We utilized a simple random sampling Technique to enroll eligible patients. We excluded patients with auto-immune diseases as rheumatoid arthritis, Behçet’s disease, and myasthenia gravis.Data collection:All patients were subjected to full history taking and clinical examination including SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI). In addition, we recorded the results of complete blood count (CBC), bleeding profile, and kidney function tests. The presence of FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A) was assessed by Real Time-Polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).Assessment of FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A)Two ml of venous blood were taken from SLE patients and controls. The blood was anticoagulated with EDTA. Total leukocyte DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Samples were collected in sterile EDTA tube and processed immediately as fresh. DNA extracts then stored at -20°C for later use. The amount of DNA was measured spectrophotometrically for concentration and purity. The detection of FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A) was done using RT-PCR Rotor - Gene Q Real Time PCR instrument from QIAGEN (Germany). The Sequence of used primers of SNPs rs1799963 was GTTCCCAATAAAAGTGACTCTCAGC[A/G]AGCCTCAATGCTCCCAGTGCTATTC.Study’s outcomes:The primary outcome in the present study was the association between the SLE and the presence of FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A). The secondary outcome was the relation between the history of cardiovascular events and FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A).Statistical Analysis:Statistical package for social science (IBM-SPSS), version 22 IBM Chicago USA was used for statistical data analysis. Data were expressed as standard deviation (SD) for quantitation data, number and percentage as described value for quantitative data. Student t-test was used to compare the mean between 2 groups; while Chi-square test was used to compare percentage of qualitative data. A p-value<0.05 is considered statistically significant.

3. Results

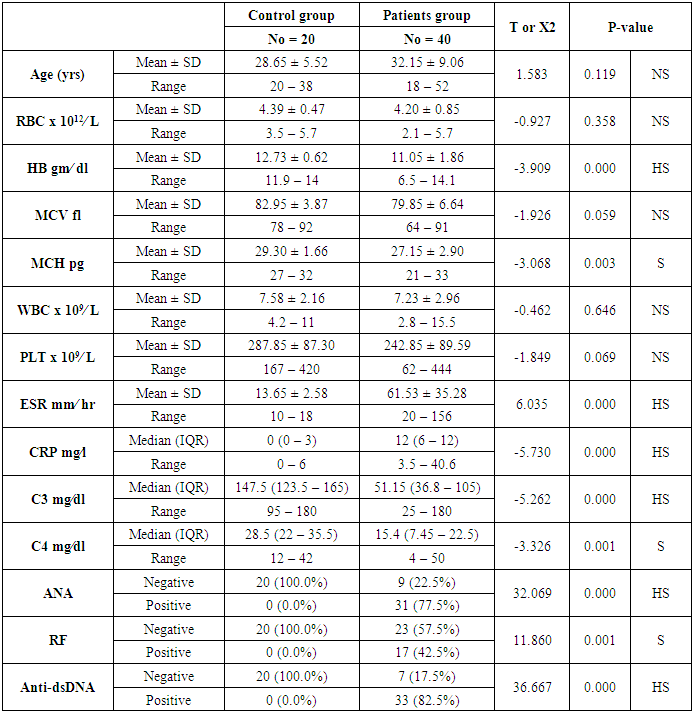

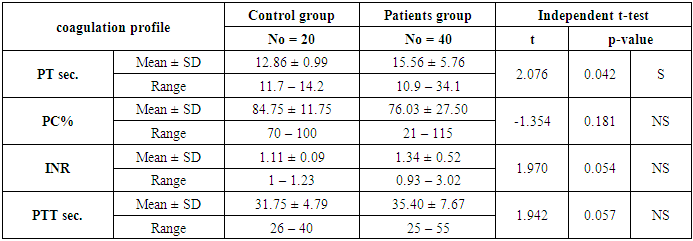

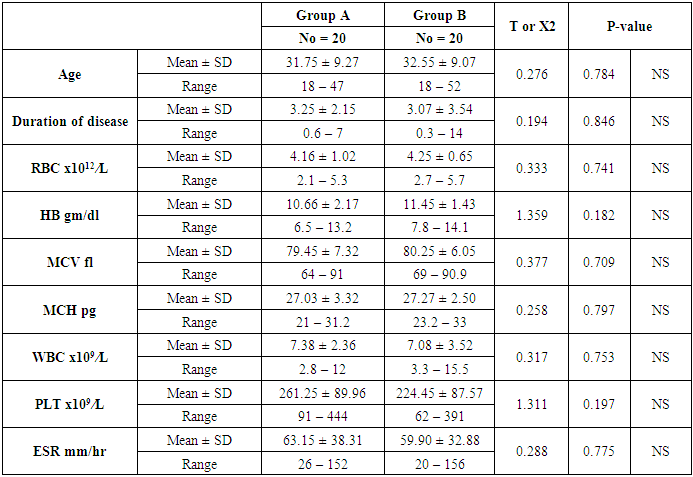

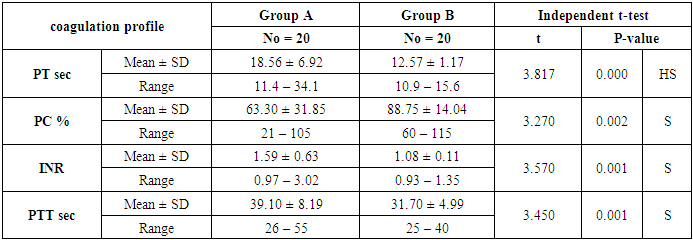

- The present study included 40 patients with SLE and 20 normal controls. The mean age of the patients was 32.15 ± 9.06 years; while all patients were female. The mean duration of disease of the included patients was 5.72 ±5.53 years. In terms of laboratory finings, there was statistically significant decrease in hemoglobin and mean corpuscular hemoglobin levels in patients in compared to controls (P<0.001 and =0.003, respectively). Also there is highly significant increase in ESR in patients in compared to controls (P <0.001). SLE patients had significantly higher CRP, ANA, RF, and Anti-dsDNA than control group (P< 0.001), while, they had significant lower C3 and C4 levels (P <0.001). Comparison between patients and controls showed significant increase in PT level in patient than controls (P=0.042).. Table 1 and 2 show the baseline and laboratory characteristics of the included patients.

|

|

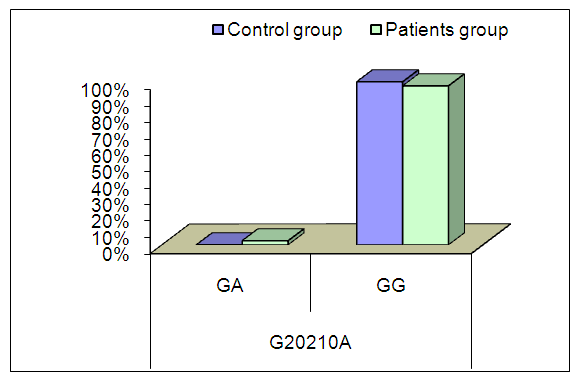

| Figure (1). Comparison between patients and controls as regard G20210A mutation |

|

|

|

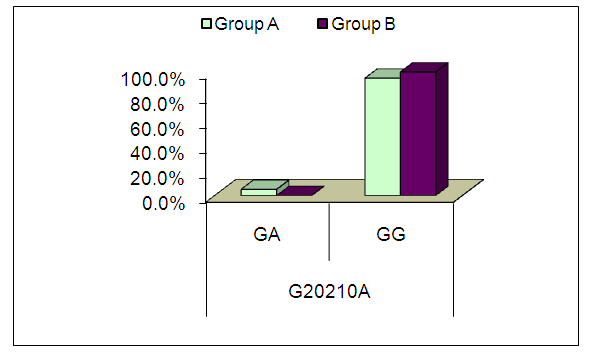

| Figure (2). Comparison between patients’ groups as regard G20210A mutation |

4. Discussion

- A Growing body of published literature has revealed a significant role of prothrombin activity in the pathogenesis and progression of cardiovascular complications in SLE, however, there are inconsistency in the published literature regarding the genetic basis of such contribution. In the present study, we found no significant difference in the frequency of FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A) between SLE patients and healthy controls. In addition, we did not observe a significant correlation between cardiovascular events risk in SLE and FII functional polymorphisms rs1799963 (G20210A).Prothrombin (factor II), a vitamin K-dependent glycoprotein, is an essential component in the coagulation cascade that is converted to thrombin in the presence of activated prothrombinase complex; in return, thrombin converts fibrinogen into fibrin which is the ultimate step in coagulation process [16]. In addition to its contribution to the coagulation cascade, thrombin participates in many physiological functions including thrombus formation and fibrinolysis [17]. Therefore, elevated prothrombin level or activity has been linked to cardiac complications including ischemic heart diseases [18]. The production of prothrombin is under genetic control by gene encoding prothrombin (F2) in which two common polymorphisms have been recognizedrs3136516 (A19911G) and rs1799963 (G20210A) [14]. G20210A is a common polymorphism that increases the risk of thrombotic events in general population; recently, a growing body of evidence suggested that G20210A polymorphism may predict a significant burden of cardiovascular comorbidities in SLE patients [14]. In our study, we found no significant difference in the frequency of G20210A between SLE patients and healthy controls.In line with our findings, an 2011 study by Demirci et al [14]., found no significant association between G20210A and SLE. However, these findings were inconsistent across different racial groups. In Afeltra et al. [19], study, the prothrombin mutation variant was present in 6 patients, which is higher than the prevalence in the control group (11% versus 4%) but was not statically significant between patients with SLE and controls.Regarding the association between G20210A and cardiovascular events, we did not observe a significant correlation between cardiovascular events risk in SLE and G20210A. Likewise, two previous prospective study from Lebanon found no association between G20210A mutation and incidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) [20,21]. Similarly, report from Egypt found no significant association between G20210A mutation and DVT [22]. Other reports found no significant association between G20210A mutation and incidence of other cardiovascular events as well Yalinkaya et al., (2006) Tabrizi et al., (2012) Silver et al., (2010).We acknowledge that the present study has number of limitations. The sample size of the included patients was relatively small which may affect the generalizability of our findings. Moreover, the study was single-center experience. In addition, we could not control for potential confounding factors such as different clinical characteristics and different treatment strategies among patients. In conclusion, SLE patients with G20210A mutation are not at increased risk of cardiovascular events. However, due to the descriptive nature of the present study, further studies on the exact role of G20210A mutation in SLE pathogenesis are still needed.

Conflict of Interest

- All authors confirm no financial or personal relationship with a third party whose interests could be positively or negatively influenced by the article’s content.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML