-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Practice

p-ISSN: 2326-1463 e-ISSN: 2326-1471

2013; 2(1): 1-3

doi:10.5923/j.cp.20130201.01

Efficacy of Emergency Cervical Cerclage

Tae-Hee Kim, Hae-Hyeog Lee, Soo-Ho Chung, Dong-Su Jeon, Junsik Park

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital,Bucheon, 420-767, Republic of Korea

Correspondence to: Hae-Hyeog Lee, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital,Bucheon, 420-767, Republic of Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Preterm birth is the primary cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality. Infants who are born at an early gestational age are at high risk of illness, injury, and handicap. To prevent preterm birth, cervical cerclage is recommended for women diagnosed with cervical insufficiency.Cervical incompetence is the inability of the cervix to retain a pregnancy until term or until the fetus is viable. Emergency cerclage is performed in patients with cervical enlargement ≥ 3cm and prolapsed membranes. We evaluated maternal and neonatal outcomefollowing emergency cerclage between 21and 26 weeksusing Foley catheter insertion.

Keywords: Premature Birth, Uterine Cervical Incompetence, Emergency

Cite this paper: Tae-Hee Kim, Hae-Hyeog Lee, Soo-Ho Chung, Dong-Su Jeon, Junsik Park, Efficacy of Emergency Cervical Cerclage, Clinical Practice, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2013, pp. 1-3. doi: 10.5923/j.cp.20130201.01.

1. Introduction

- Cervical insufficiency or incompetence is the inability of the uterine cervix to retain a pregnacy in the absence of labor or contractions.1Cervical insufficiency occurs during the second trimester and is characterized by premature, painless cervical dilatation during gestation in the absence of uterine contractions followed by expulsion of the immature fetus. The pathophysiology of the condition is not known; however, the incompetent cervix has a less elastic component both morphologically and biochemically than the normal cervix.2Traumato the cervix, forceful dilatation, and obstetric lacerations increase the risk of insufficiency.3 Thus,several investigations of surgical treatment for cervical insufficiency have been conducted. The simplest and most common cervical cerclageprocedure is the purse-string suture developed by McDonald (1957) in which the upperpart of the cervix is stitched using a band of suture when the lower part has shown significant effacement.4 Cervicalcerclage should be performed after 14 weeks’ gestation to avoid overlap with a spontaneous first-trimester abortion. However, elective cerclage performed before 20 weeks’ gestation to avoid cervical dilatation or effacement provides the best results. The procedure itself can cause membrane rupture, premature contraction, or cervical dystocia (inability of the cervix to dilate normally during the course of labor), discomfort or mild cramping, vaginal spotting or bleeding, and infection of the cervix.We evaluated the maternal and neonatal results of emergency cerclageusing Foley catheter insertion between week 21and 26.

2. Case Series

- The present report describes eight consecutive emergency cervical cerclage cases performed on patients 28–38 years old (median, 32 years) with a cervical dilatation between 3 and 10 cm and prolapsed membranes as diagnosed by pelvic examination at our university hospitalbetween March 2003 and March 2007 (Fig. 1).The pelvic examination revealed bulging membranes more than 3cm from the cervix.The patients underwent emergency cerclage afterwe excludedof labor, placental abruption, andintrauterine infection.

| Figure 1. Pelvic examination revealed membrane bulging before emergency operation |

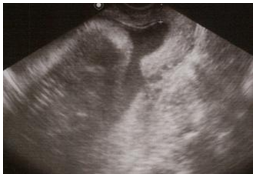

| Figure 2. Ultrasonography revealed a cervical length of less than 1 cm after surgery |

3. Discussion

- Cervical incompetence is characterized by premature, painless cervical dilatation during gestation in the absence of uterine contractions, followed by expulsion of the immature fetus. Cervical incompetence in our cases was diagnosed by digital examination and confirmed using transvaginal ultrasonogaphy. Digital examination of the cervix is the oldest method of assessing the risk of preterm pregnancy loss.Studies comparing digital assessment with ultrasonography have reported inconsistent results. The Research Group in Obstetrics and Gynecology (GROG) study found that transvaginal ultrasound predicted spontaneous delivery before 34 weeks of gestation better than digital examination at the 27-week but not the 22-week examination.5Several studies have investigated transvaginal ultrasonography for the measurement of cervix length,6-10 and found it to provide an accurate and valid measurement of the cervix10and to be a useful method for predicting women at risk for preterm delivery.8Cervix lengthhas been reported to be inversely proportional to the risk of preterm birth.7The earliest changes at the internal uterine cervix are generally asymptomatic and can only be detected using transvaginal ultrasonography.Several factors are associated with a high risk of preterm birth. Cervix length is a good predictor of preterm birth in women at high risk, such as those who have had a prior preterm birth,11 prior cone biopsy,12 prior multiple dilatation and curettage (D&C)13or Mulleriananomalies.14 Three of our cases had risk factors for cervical incompetence. Previous preterm birth and loop electrosurgical excision procedure(LEEP) conization are important risk factors for cervical incompetence. Moreover, twin pregnancy has a high risk for preterm labor, and has been documented to be as high as 68.4% in Austria and 42.2% in the Republic of Ireland.15 Women with uterine anomalies and a short cervix, as indicated by transvaginal ultrasound, have a 13-fold increase in spontaneous preterm birth, and women with a unicornate uterus have the highest rate of preterm birth.16The effect of cerclage in women with no previous preterm birth and a short cervix length is not known; however, it is not expected to be as great as that for women who have experienced a previous preterm birth. Cervical cerclage is associated with a 30–40% reduction in preterm birth in women who have had a previous preterm birth, whereas the reduction is predicted to be 10–30%, at most, in women with no previous preterm birth.17The benefit of prophylactic cerclage in women with a history of conization is not clear.12Leimanet al.18 concluded that all pregnancies after a cone biopsy should be regarded as high risk, and recommende dcerclage for pregnancies following extensive cone biopsy. In contrast, Kullander and Sjoberg18->19were unable to show that cerclage reduced the incidence of preterm delivery in women after conization and concluded that the procedure should be avoided. Myllynen and Karjalainen20 and Zeisleret al.21proposed that prophylactic cerclage should be used sparingly because it does not prevent preterm delivery and tends to induce preterm uterine contractions. However, we found that emergency cerclage prevented preterm labor in women who had had a previous preterm birth or LEEP conization. On the other side of the benefit-versus-risk equation, most series in the literature indicate a low major complication rate. Postcerclagechorioamnionitis occurred in 0.8–3.5 % of the patients in a major series.22-25Transvaginalcerclage can be performed prophylactically during the first trimester. Two studies have shown that a prophylactic cerclage prevents the shortening of cervical length in about 90% of at-risk women.26Atransabdominal approach to repair cervical incompetence during pregnancyintroduced by Benson and Durffee27 has attracted significant interest within the obstetric community. Several series that included several hundred women have reported that TCC is a viable alternative for women with recurrent second trimester loss or early preterm delivery for whom transvaginal cervical cerclage was ineffective or who had short or scarred cervices. The optimal treatment for cervical insufficiency is controversial, and the preventive role of cerclageis highly debatable.Emergency cerclage should be considered as a management option in women with painless cervical dilatation and prolapsed membrane in the mid-trimester.

Competing Interests

- The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

- All authors conceived the study concept and design, collected clinical data, reviewed the literature on the topic, and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML