-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Computer Science and Engineering

p-ISSN: 2163-1484 e-ISSN: 2163-1492

2025; 15(6): 161-168

doi:10.5923/j.computer.20251506.05

Received: Nov. 20, 2025; Accepted: Dec. 10, 2025; Published: Dec. 13, 2025

Privacy-Aware Data Taxonomy for Data Governance: A Multi-Dimensional Framework Bridging Classification and Regulatory Compliance

Prabal Pathak

Principal PM Architect, Microsoft, Apex, NC

Correspondence to: Prabal Pathak, Principal PM Architect, Microsoft, Apex, NC.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Effective data governance and privacy protection depend on a clear understanding of what data an organization holds and how it is organized. Existing data governance taxonomies, such as Al-Ruithe et al.’s cloud versus non-cloud taxonomy, focus on governance structures (roles, processes, technologies) but provide limited guidance on how to classify data objects themselves in a privacy-aware way. At the same time, many enterprises rely on simple sensitivity labels (public, internal, confidential) that are too coarse to support modern regulatory requirements under the GDPR, CCPA/CPRA, the EU AI Act, and India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA). This paper proposes the Privacy-Aware Data Taxonomy for Governance (PADT-G), a multi-dimensional taxonomy that combines business domain and entity, identifiability, sensitivity, regulatory obligations, and lifecycle and usage context. Building on prior taxonomic work in data governance, we derive design principles, define PADT-G’s dimensions, and illustrate its application to a regulated analytics environment. We also show how PADT-G directly drives governance controls such as data ownership, lawful basis, access management, retention, data protection impact assessment (DPIA) triggers, and AI training data selection. The contribution of this work is to bridge business-oriented data taxonomies and privacy regulation, offering a practical, data-centric framework for operationalizing privacy by design in enterprise data governance.

Keywords: Data taxonomy, Data governance, Data privacy, GDPR, CCPA, EU AI Act, DPDPA, Data classification

Cite this paper: Prabal Pathak, Privacy-Aware Data Taxonomy for Data Governance: A Multi-Dimensional Framework Bridging Classification and Regulatory Compliance, Computer Science and Engineering, Vol. 15 No. 6, 2025, pp. 161-168. doi: 10.5923/j.computer.20251506.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Data governance has evolved from a narrow IT concern into a strategic capability underpinning digital transformation, analytics, and regulatory compliance. Foundational work has [1], [11] framed data governance as the assignment of decision rights, accountabilities, and processes for managing data as an organizational asset. Yet, in day-to-day practice, many governance programs struggle with a basic question: Do we have a consistent way to describe and organize our data so that governance and privacy controls can be applied reliably?A data taxonomy provides that organizing backbone by structuring data into a hierarchy of domains, entities, attributes, and categories that reflect business meaning and technical reality. In parallel, data classification schemes label data according to sensitivity and risk (e.g., public, internal, confidential, restricted) and increasingly incorporate regulatory considerations such as personal data, special category data, or protected health information. However, these two worldsbusiness-oriented taxonomies and security/privacy-oriented classificationare often designed and managed separately, limiting their effectiveness for data governance and privacy by design.Recent research by Al-Ruithe et al. introduced a data governance taxonomy that differentiates cloud versus non-cloud environments and identifies key attributes (e.g., roles, policies, technologies) that shape governance strategies. This work usefully clarifies how organizations can structure governance capabilities, but it does not define a taxonomy of the data itself that is rich enough to drive privacy-aware decisions at the level of datasets, tables, or attributes. [3]At the same time, regulatory frameworks such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA, as amended by the CPRA), the EU AI Act, and India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) explicitly require organizations to know what personal data they process, under which legal basis, with which safeguards, and, increasingly, how such data is used in AI and automated decision-making systems. Effective compliance hinges on accurate classification and inventory of personal and sensitive data, not only at system level but down to data elements and processing contexts.This paper addresses that gap by proposing a Privacy-Aware Data Taxonomy for Governance (PADT-G) that integrates business-centric data taxonomy (domains, entities, attributes), privacy-centric facets (identifiability, sensitivity, data subject category), regulatory obligations (GDPR/CCPA/DPDPA categories, lawful basis, data subject rights), and lifecycle and usage context (analytics, AI training, operational processing, sharing).

1.1. Research Problem and Objectives

- The central research question guiding this work is: How can a multi-dimensional, privacy-aware data taxonomy be designed so that it directly informs data governance and privacy controls at scale?Our objectives are to:• Synthesize prior research and practice on data governance taxonomies, data taxonomy, and data classification for privacy.• Analyze limitations of existing approaches in supporting granular, regulation-aligned governance decisions.• Propose the PADT-G framework as a novel, multi-dimensional taxonomy model that makes privacy obligations explicit at the data-object level.• Illustrate how PADT-G can be instantiated in an enterprise environment and how it drives specific governance decisions (e.g., ownership, access, retention).

1.2. Structure of the Paper

- Section 2 reviews related work on data governance, data taxonomy, and data classification for privacy, and highlights Al-Ruithe et al.’s data governance taxonomy as our base paper. Section 3 describes the research methodology and design principles. Section 4 presents the PADT-G framework in detail. Section 5 discusses implementation considerations, implications for AI and analytics, and alignment with key regulations including GDPR, CCPA, the EU AI Act, and India’s DPDPA. Section 6 concludes and outlines future research.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Data Governance and Its Taxonomies

- Data governance literature has matured over the last decade, offering definitions, frameworks, and maturity models. Khatri and Brown conceptualize data governance as specifying decision rights and accountabilities for information-related processes, supported by policies, standards, and controls. Otto’s morphology of the organization of data governance characterizes governance design options (centralized, decentralized, hybrid) along structural dimensions such as roles, decision processes, and mechanisms. Building on this foundation, Al-Ruithe et al. propose a data governance taxonomy for cloud versus non-cloud, identifying categories such as governance domains, decision areas, and technological enablers, and then comparing how these appear in cloud and traditional environments. Their taxonomy clarifies where and how governance must adapt to cloud but does not drill into the internal structure of the data assets themselves. [1] [2]

2.2. Data Taxonomy in Practice

- In parallel, industry practice has developed data taxonomies to make data discoverable, usable, and governable. A data taxonomy is typically a hierarchical classification of data into domains (e.g., Customer, Product, Finance), entities (e.g., Customer Profile, Purchase Order), and attributes, often implemented in data catalogs or master data management systems. Well-designed taxonomies improve data discoverability, semantic consistency, and cross-functional collaboration. They also support governance by making it easier to assign ownership, define quality rules, and document lineage. However, many taxonomies are primarily business-semantic and do not encode privacy-sensitive facets such as identifiability or legal data categories, leading privacy teams to build separate sensitive data inventories or records of processing activities that are only loosely connected to the core taxonomy.

2.3. Data Classification for Privacy and Security

- Data classification frameworks, especially in security, label data according to sensitivity, criticality, and riskcommonly using levels like Public, Internal, Confidential, and Restricted. Modern guidance increasingly recommends mapping these levels to regulatory categories (e.g., personal data, special categories, children’s data) and using them to drive risk-based protections. Commentators also note the limitations of simplistic classification when used alone: labels can be too coarse, lack context, and be inconsistently applied across tools. Many organizations thus end up with parallel classification schemes in data loss prevention tools, data catalogs, and privacy registers, leading to fragmentation. [6]–[10] [7], [8] [6], [9], [10]

2.4. Gap and Base Paper

- Existing data governance taxonomies, including Al-Ruithe et al.’s cloud versus non-cloud taxonomy, focus primarily on governance structures rather than the internal structure of data assets and their privacy attributes. They typically: (1) describe who makes which data decisions and how governance is organized, (2) differentiate environments such as cloud and non-cloud, and (3) enumerate governance mechanisms such as roles, policies, and technologies. While this clarifies organizational arrangements, it leaves several gaps for privacy-aware governance at the data-object level:• Limited representation of privacy semantics. Regulatory categories such as personal data, special categories, children’s data, or AI training data are usually not first-class elements of existing taxonomies.• Single-label classification bias. Many frameworks rely on a single sensitivity label (e.g., public, internal, confidential) rather than a multi-dimensional view that captures identifiability, lifecycle, and use context.• Weak linkage to concrete controls. The mapping from taxonomic attributes to specific governance and privacy controls (ownership, lawful basis, DPIA triggers, AI eligibility, retention) is often implicit or tool-specific rather than explicit and reusable.Taking Al-Ruithe et al. (2018) as a base, this paper extends the taxonomic lens from governance structures to the taxonomy of the data itself. The proposed Privacy-Aware Data Taxonomy for Governance (PADT-G) is explicitly designed to address the above gaps by: (1) embedding regulatory and privacy semantics as a separate dimension, (2) treating classification as one facet within a broader multi-dimensional model, and (3) defining explicit mappings from taxonomy values to governance and privacy controls. [3]

3. Research Methodology

- This study follows a conceptual design science approach, aiming to design and justify an artifactin this case, the PADT-G taxonomygrounded in existing knowledge and oriented toward practical use. Design science is appropriate when the primary contribution is a purposeful artifact that addresses a relevant problem and whose utility can be reasoned about and, where possible, demonstrated. In our context, the problem is the lack of a privacy-aware data taxonomy that is both multi-dimensional and directly linked to governance and regulatory controls.

3.1. Problem Identification and Motivation

- We began by articulating the practical problem from the perspective of enterprise data governance and privacy teams: organizations struggle to maintain a consistent, regulation-aware view of their data assets, especially when the same datasets are reused across operational, analytics, and AI contexts. Existing taxonomies tend to be business-semantic, while classification schemes are security-centric and tool-specific. This leads to fragmentation, duplicated effort, and difficulties in demonstrating accountability under laws such as the GDPR, CCPA/CPRA, the EU AI Act, and India’s DPDPA.Through this analysis we derived the central research question: How can a multi-dimensional, privacy-aware data taxonomy be designed so that it directly informs data governance and privacy controls at scale?

3.2. Literature Synthesis

- A targeted literature review was performed covering three strands: (1) academic work on data governance definitions, frameworks, and taxonomies; (2) practitioner material and tooling documentation on data taxonomies and catalog-driven governance; and (3) regulatory and industry guidance on data classification for privacy and AI. The search focused on terms such as “data governance taxonomy,” “data taxonomy,” “data classification for GDPR,” and “privacy-aware data governance,” using major digital libraries and practitioner sources. [4]–[10]From this corpus we extracted:• structural patterns of existing taxonomies (e.g., domain/entity hierarchies, governance domains),• common limitations noted in practice (e.g., silos between catalogs and privacy registers), and• regulatory requirements that have direct implications for taxonomy design (e.g., explicit identification of special categories, children’s data, and AI training data).These insights informed both the scope of PADT-G (which dimensions to include) and the granularity at which it should operate (dataset, table, and attribute levels).

3.3. Derivation of Design Principles and Framework Construction

- Based on the literature synthesis and observed shortcomings, we formulated design principles such as “business first, privacy always,” “multi-dimensional, not single-label,” “regulation-aligned and extensible,” and “operationalizable in tooling.” For each principle, we identified corresponding design choices. For example, the principle of multi-dimensionality motivated the separation of identifiability, sensitivity, regulatory obligations, and lifecycle/usage context as distinct facets rather than embedding them in a single sensitivity label.We then iteratively constructed the PADT-G framework by:• defining the five primary dimensions and their core value sets,• specifying how those dimensions apply at the level of domains, entities, datasets, and attributes, and• drafting explicit mappings from combinations of dimension values to governance and privacy controls (e.g., access policies, DPIA triggers, AI training eligibility, retention schedules).Interim versions of PADT-G were checked against representative scenarios drawn from regulated analytics and AI environments to ensure that common use cases (e.g., marketing analytics, HR reporting, AI training corpora) could be expressed without undue complexity.

3.4. Design Science Justification

- The choice of a design science methodology is justified by the nature of the contribution. The goal is not to test a causal hypothesis about data governance, but to propose an artifact that addresses a recognized gap and to reason about its utility. PADT-G embodies a set of design decisions that can be evaluated along established design science criteria such as:• Relevance: The taxonomy addresses concrete needs of data governance, privacy, and AI governance teams operating under multiple regulatory regimes.• Rigor: The dimensions and mappings are grounded in prior taxonomic work, regulatory requirements, and widely used governance practices.• Design quality: The artifact is internally coherent, extensible, and implementable in contemporary data catalog and governance platforms.• Utility: The taxonomy is shown, through illustrative application, to support tasks such as assigning ownership, determining lawful basis, and scoping AI training data.

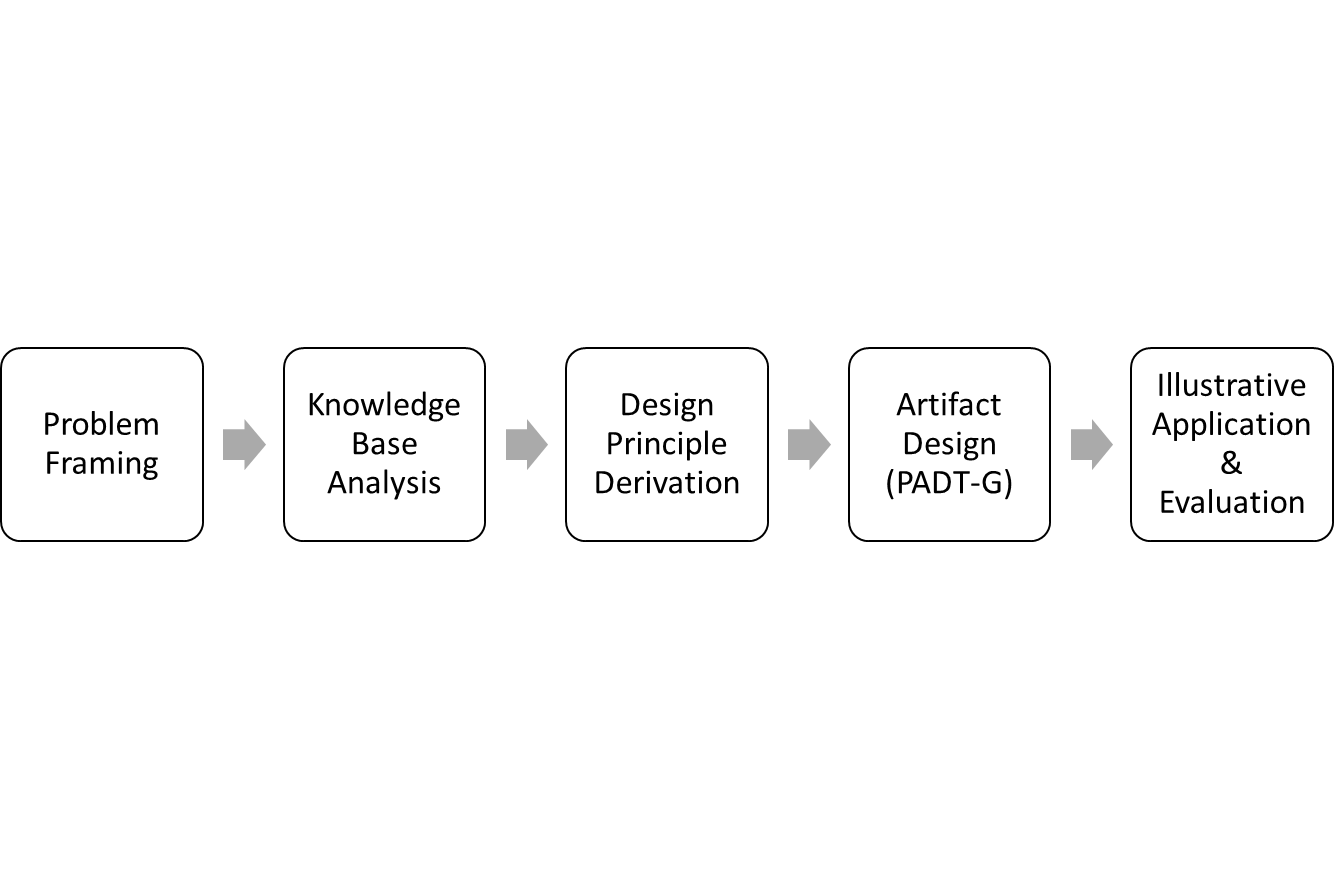

3.5. Schematic of the Design Process

- Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the design process used in this study. The process consists of five stages:1. Problem framing: articulating the need for a privacy-aware data taxonomy and scoping the regulatory and organizational context.2. Knowledge base analysis: synthesizing prior work on data governance taxonomies, taxonomic practice, and privacy-oriented classification.3. Principle derivation: formulating design principles that connect the problem context with insights from the knowledge base.4. Artifact design: defining PADT-G’s dimensions, value sets, and mappings to governance controls.5. Illustrative application and evaluation: applying PADT-G to a representative enterprise scenario to assess expressiveness and usefulness, and refining the artifact as needed.

| Figure 1. Design Process for PADT-G |

4. Privacy-Aware Data Taxonomy for Governance (PADT-G)

4.1. Design Principles

- • Business First, Privacy Always: The taxonomy should reflect how the business thinks about data (domains, entities, processes) while embedding privacy attributes directly into those structures, rather than in a separate, privacy-only catalog.• Multi-Dimensional, Not Single-Label: A single classification label is insufficient. The taxonomy must capture multiple facetssuch as identifiability, sensitivity, regulatory category, and lifecycleto support nuanced governance decisions.• Regulation-Aligned and Extensible: Taxonomy facets should map explicitly to regulatory concepts (e.g., personal data, special category data, data subject rights, automated decision-making) and be extensible across jurisdictions as laws evolve.• Operationalizable in Tooling: The taxonomy must be implementable in data catalogs and governance platforms, with clear mappings to controls such as access policies, masking rules, and retention schedules.

4.2. Taxonomy Structure and Dimensions

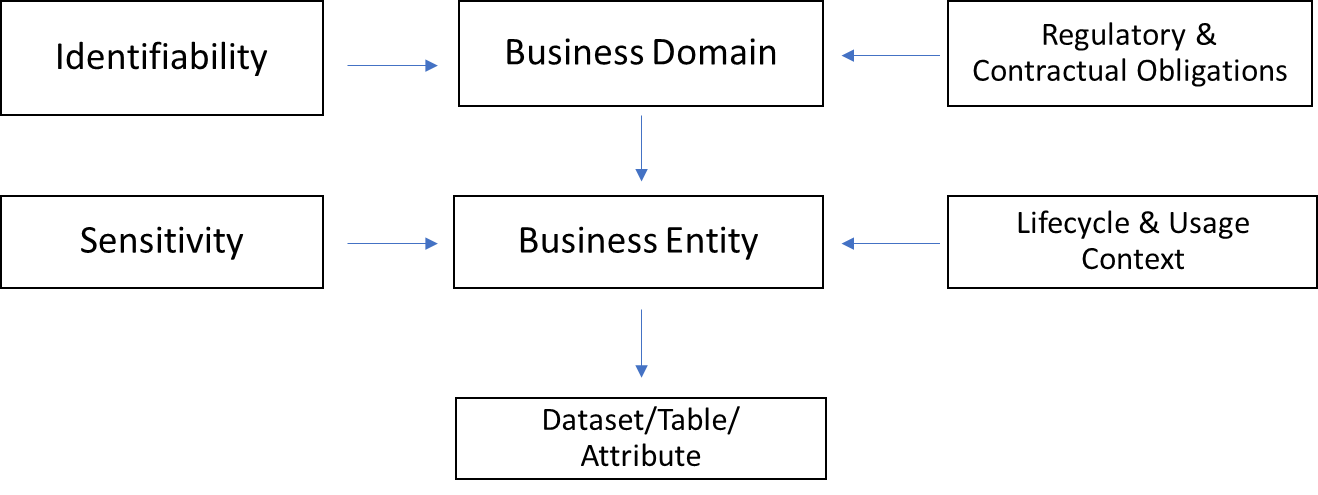

- PADT-G is structured along five primary dimensions that together characterize each data object (e.g., dataset, table, column, event type).• Business Domain and Entity (What is it about?): Domain (Customer, Product, Finance, HR, Operations, etc.) and Entity (Customer Profile, Transaction, Invoice, Employee Record, Device Log, etc.).• Identifiability (Whose data and how identifiable?): Non-personal data; personal data – identified; personal data – identifiable via quasi-identifiers; pseudonymous data; anonymized data that meets internal standards for irreversibility.• Sensitivity and Special Categories (How sensitive is it?): Low, medium, and high sensitivity levels, plus special categories and sensitive personal data as defined by regulations (health, biometric, racial or ethnic origin, children’s data, etc.).• Regulatory and Contractual Obligations (Which rules apply?): Regulatory categories (GDPR personal data and special category data, CCPA/CPRA personal information and sensitive personal information, India DPDPA digital personal data and significant data fiduciary obligations, sectoral rules such as HIPAA PHI), lawful basis, data subject category, automated decision-making and AI use, and cross-border restrictions.• Lifecycle and Usage Context (How and where is it used?): Lifecycle state (newly collected, active, archived, scheduled for deletion); processing context (operational processing, analytics/reporting, AI/ML training, automated decision-making, sharing with processors/partners); and storage and transfer patterns (on-premise, cloud SaaS, data lake, streaming, batch, third-party APIs).

4.3. Example Taxonomy Assignment

- Consider a column customer_email in a Customer_Profile table within the Customer domain in a retail organization. Using PADT-G:• Business Domain & Entity: Domain = Customer; Entity = Customer Profile.• Identifiability: Personal data – identified (direct identifier).• Sensitivity: Medium to high (used for communication; high phishing and misuse risk).• Regulatory & Contractual: GDPR/DPDPA/CCPA personal data; lawful basis may include consent (for marketing) and contract (for service communications); data subject category = customer; cross-border restrictions may apply for transfers to non-adequate countries or high-risk processors.• Lifecycle & Usage Context: Lifecycle = active; processing context = operational (order updates) and marketing analytics; storage = regional cloud data lake synchronized to CRM SaaS.By contrast, an aggregated daily_sales_region dataset might be categorized as non-personal, low to medium sensitivity, primarily subject to commercial confidentiality and records retention requirements rather than data-protection law. These examples illustrate how PADT-G differentiates data objects in a way that makes privacy-related obligations explicit while remaining grounded in business semantics.

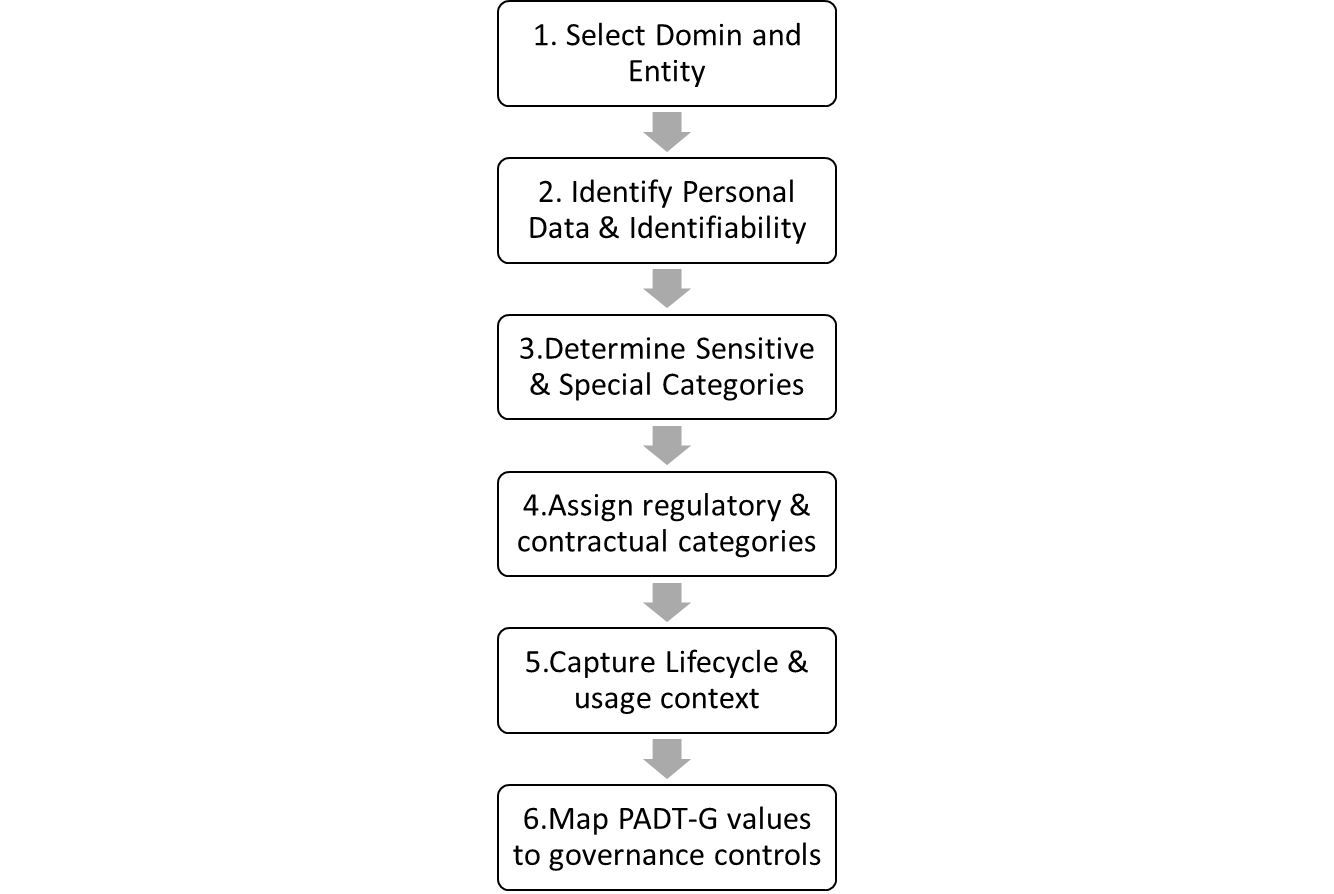

| Figure 3. Provides a generic workflow for assigning PADT-G values to datasets |

4.4. From Taxonomy to Governance Controls

- The power of PADT-G lies in its explicit mapping to governance and privacy controls. Table 1 summarizes exemplary mappings from PADT-G dimensions to typical governance and compliance controls. For each dimension and combination of values, organizations can define data ownership, access and usage policies, retention and deletion rules, data protection impact assessment (DPIA) triggers, and cross-border and third-party governance requirements.

|

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Existing Data Governance Taxonomies

- Compared with Al-Ruithe et al.’s cloud versus non-cloud data governance taxonomy, PADT-G shifts the focus from governance structures (e.g., roles, processes) to governance of data objects enriched with privacy semantics. Both approaches are complementary: Al-Ruithe et al. help define how governance is organized and how it changes in cloud environments, while PADT-G helps define what is being governed and which privacy and compliance constraints apply at the lowest practical level. We also differ from typical data classification frameworks by making the classification one dimension among several within the taxonomy, explicitly integrating identifiability, regulatory categories, lifecycle context, and AI/ADM usage rather than encoding all nuance into a single label. [3]

5.2. Implementation Considerations

- Implementing PADT-G in an enterprise setting raises several practical questions. First, it is rarely feasible to label every attribute across all systems at once. A pragmatic approach is to start with high-risk domains (Customer, Patient, HR), high-value analytics environments, or AI training corpora, and gradually expand. Second, organizations must balance automation and human judgment: automated discovery tools can suggest taxonomy values, but final decisions about regulatory categories, lawful basis, and AI risk require collaboration between privacy, legal, security, and data owners. Third, the taxonomy itself needs governanceroles, change processes, and quality checksto stay aligned with organizational needs. Finally, PADT-G should be implemented through a central data catalog or metadata platform that integrates with access control systems, DLP, and privacy tools, avoiding the fragmentation that plagues many data governance initiatives. [12]

5.3. Implications for AI and Advanced Analytics

- The emergence of AI and large-scale analytics introduces new privacy and fairness risks when data is repurposed for training or inference. Recent regulatory developments, including the EU AI Act and data protection guidance on AI, emphasize data minimization, purpose limitation, quality, and transparency across AI pipelines. PADT-G can support these objectives by making explicit which datasets contain special category personal data or children’s data, and thus may be unsuitable or high-risk for training general-purpose models; by highlighting when originally operational data is repurposed for analytics or AI, potentially triggering additional legal analysis or DPIAs; and by enabling AI governance teams to filter and select training data based on taxonomy attributes (e.g., only non-personal or properly anonymized data for certain use cases).

5.4. Illustrative Application and Evaluation in a Regulated Analytics Environment

- To provide an initial, illustrative evaluation of PADT-G, consider a hypothetical but realistic scenario of a financial services organization implementing the taxonomy in its cloud-based analytics environment. The environment hosts approximately fifty curated datasets across Customer, Product, and Risk domains, with mixed usage for reporting and AI model development.The organization’s current practice combines a simple four-level sensitivity classification (Public, Internal, Confidential, Restricted) with ad-hoc privacy registers maintained in spreadsheets. Applying PADT-G proceeds in three steps:1. Scoping and selection. High-risk domains (Customer and Risk) and AI training datasets are prioritized. For these datasets, data owners and stewards are identified in the business domain/entity hierarchy.2. PADT-G annotation. For each dataset and selected key attributes, identifiability (e.g., personalidentified vs pseudonymous), sensitivity (e.g., financial account data, children’s data), regulatory obligations (e.g., GDPR personal data, CCPA sensitive personal information, DPDPA digital personal data), and lifecycle/usage context (e.g., operational reporting, AI model training) are assigned.3. Control mapping. Governance rules are defined that map combinations of PADT-G dimension values to controls such as access policies, masking rules, lawful-basis templates, retention schedules, and AI training eligibility criteria.Even without a full empirical deployment, we can define indicative evaluation metrics for such a rollout, for example:• Coverage: proportion of prioritized datasets for which all PADT-G dimensions are populated.• Consistency: proportion of attributes for which identifiability and regulatory categories are consistently assigned across systems (e.g., customer_email classified identically in CRM and data lake).• Control alignment: proportion of datasets where access and retention policies are automatically derived from PADT-G values rather than maintained separately.• Regulatory traceability: ability to answer regulatory questions (e.g., “Which datasets involve children’s data used for AI training?”) via simple queries over PADT-G-annotated metadata.In our hypothetical scenario, introducing PADT-G enables the organization to move from an environment where privacy-relevant information is scattered across multiple tools to one where a single, multi-dimensional taxonomy supports both traditional governance tasks (ownership, quality, lineage) and privacy-specific tasks (lawful-basis assignment, DPIA scoping, AI training data selection). While a full empirical evaluation is outside the scope of this conceptual study, this scenario illustrates how PADT-G can be evaluated in practice using coverage, consistency, control-alignment, and traceability metrics as the taxonomy is adopted.

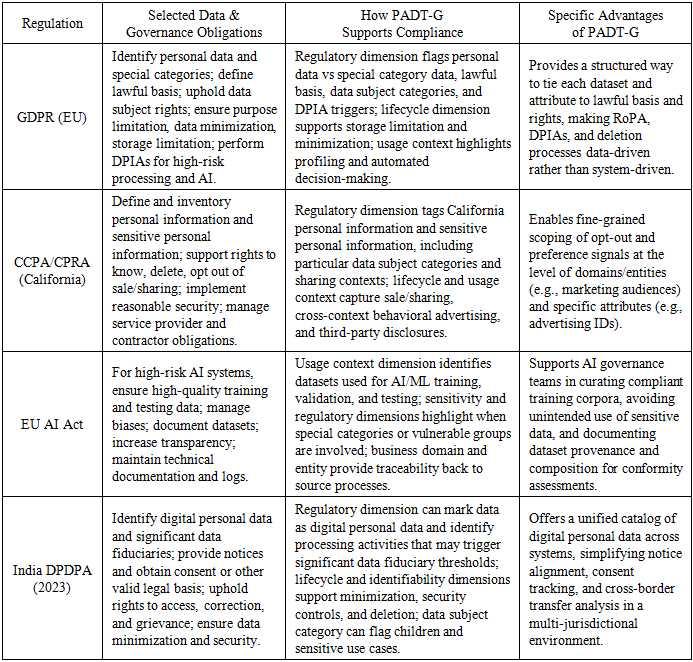

5.5. Regulatory Alignment and Comparative Advantages

- To make the regulatory mapping more concrete, Table 2 compares how core legal categories from the GDPR, CCPA/CPRA, and India’s DPDPA can be represented using PADT-G’s Regulatory and Contractual Obligations dimension. Rather than maintaining three separate, law-specific classification schemes, organizations can encode these categories as structured values within PADT-G and allow the same dataset to carry multiple regulatory labels (for example, both “GDPR personal data” and “CCPA personal information”) that in turn drive localized governance rules.

|

6. Conclusions and Future Work

- This paper has argued that a privacy-aware data taxonomy is a missing piece in many data governance programs. While existing taxonomies clarify governance structures and while classification schemes label data by sensitivity, there is a gap in connecting business-semantic taxonomies with privacy and regulatory obligations at the data-object level. Building on Al-Ruithe et al.’s data governance taxonomy for cloud versus non-cloud environments, we proposed the Privacy-Aware Data Taxonomy for Governance (PADT-G), a multi-dimensional framework that characterizes data by business domain, identifiability, sensitivity, regulatory obligations, and lifecycle/usage context.The primary contribution of PADT-G is to make privacy and regulatory requirements first-class citizens of the data taxonomy, enabling organizations to operationalize privacy by design in a scalable way. Rather than treating taxonomy and classification as separate, PADT-G unifies them into a single, governance-ready model that can be implemented in data catalogs and governance platforms. Future work could extend this conceptual framework in several directions, including empirical evaluation in different sectors, development of quantitative metrics to assess taxonomy coverage and correctness, integration with privacy-enhancing technologies such as differential privacy or federated learning, and exploration of how PADT-G can be combined with emerging AI-specific governance frameworks to create an end-to-end view from raw data to model deployment.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML