-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Computer Science and Engineering

p-ISSN: 2163-1484 e-ISSN: 2163-1492

2025; 15(6): 136-145

doi:10.5923/j.computer.20251506.02

Received: Oct. 10, 2025; Accepted: Nov. 2, 2025; Published: Nov. 7, 2025

Collaborative Intelligence for Adaptive Planning: Bringing Human-Centric CPPS to Industry 5.0 Regulated Manufacturing

Tejaskumar Vaidya1, Devayani Borse2, Chandra Jaiswal3, Ramakrishnan Rajagopal2

1AdvanSoft International, USA

2Independent Researcher, USA

3North Carolina Agricultural and Technical University, Greensboro, NC, USA

Correspondence to: Tejaskumar Vaidya, AdvanSoft International, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The rise of Industry 5.0 centers around sustainable, human-centric, and resilient manufacturing with the shift from automation dominated Industry 4.0 mindset. As part of this transformation, the role of the Cyber-Physical Production Systems (CPPS) is critical in aligning digital advanced technology with human experience to bring about adaptive, compliant, and value-centric manufacturing. The paper envisions the concept of the integration of human-centric CPPS in regulated manufacturing processes with special emphasis on adaptive planning in the context of stringent compliance needs. The framework, based on the simulated study structure, demonstrates how digital twins, decision support with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI), and human in-the-loop regulation mechanisms can be synchronized to balance efficiency, regulation conformance, and workers’ well-being. The simulated scenarios compare the traditional planning, automated CPPS, and human-centric adaptive planning to reveal better levels of compliance, disruption withstanding, and workforce morale when human agency is introduced in the loops of decision. Research study opens the gap for empirical pilots in pharmaceuticals, aerospace, and medical devices manufacturing industries. Through the positioning of people as co-collaborators with intelligent systems, the study identifies Industry 5.0’s potential to build resilient, ethical, and compliant manufacturing systems that redefine regulated manufacturers near future.

Keywords: Industry 5.0, Cyber-Physical Production Systems, Human-centric Manufacturing, Adaptive Planning, Regulated Manufacturing, Digital Twin

Cite this paper: Tejaskumar Vaidya, Devayani Borse, Chandra Jaiswal, Ramakrishnan Rajagopal, Collaborative Intelligence for Adaptive Planning: Bringing Human-Centric CPPS to Industry 5.0 Regulated Manufacturing, Computer Science and Engineering, Vol. 15 No. 6, 2025, pp. 136-145. doi: 10.5923/j.computer.20251506.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The manufacturing sector has witnessed continuous waves of industrial revolutions that have continually redefined patterns of production. The world of manufacturing was introduced to cyber-physical systems, automation, and digitalization under the umbrella of Industry 4.0, bringing with that unprecedented connectivity among machines, information, and the decision-making function. However, the emphasis on technological autonomy revealed intrinsic limitations: immutable production architecture, susceptibility in being compliant with laws, and the marginalization of the role of human agency in the decision-making function. These lacunae become largely visible in the highly regulated manufacturing sectors like pharmaceuticals, aerospace, and medical devices, in which compliance and adaptability coexist. Industry 5.0 was conceived in response as the new paradigm that centers resilience, sustainability, and, above all, human-centric cooperation among people and machines [1].In this energetic context, the Cyber-Physical Production Systems (CPPS) constitute the future-proof foundation of the manufacturing ecosystems. They merge physical assets, in-built sensors, communication networks, along with intelligent data analytics, self-optimization as well as networked production environments. Though the CPPS are extensively implemented under the industry 4.0 paradigm as well, in an Industry 5.0 scenario, their potential is yet untapped, particularly with reference to the integration of human values as well as adaptive planning functionalities. The human-centric CPPS is more than the technical augmentation but is the paradigm shift in which the worker is the proactive collaborator as well as the decision maker, with the support of the tools powered by artificial intelligence as well as digital twins that support—and not substitute—their judgment. Such an orientation is in tune with the ethical, societal, as well as environmental priorities that Industry 5.0 intends to institutionalize [2].The greatest difficulty in regulated manufacturing is how flexibility can be attained while the compliance is not sacrificed. The regulating authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and aerospace standard bodies demand high levels of documentation, traceability, and verification of quality. These requirements, while assuring safety and reliability, bring inflexibility in the scheduling and planning. The traditional planning systems are not well equipped in fulfilling the dual needs of flexibility and compliance, which lead to inefficiencies, hazards in compliance, and disengagement of the workforce. The challenge demands new architectures that combine adaptive planning functionalities in the CPPS while ensuring that the regulated needs are systematically addressed [3] [4].The current study meets this challenge through the introduction and examination of a human-focused CPPS framework of adaptive planning in regulated manufacture. Since empirical evidence from highly regulated sectors is frequently unavailable due to secrecy and intellectual property constraints, the study opts instead for a simulation driven design in order conceptually to validate the framework. Simulated case scenarios based on exemplars like pharmaceutical batch manufacture or aerospace assembly can be used to test dynamic planning approaches in the face of shifting demand, acts of regulatory audit, and diverse levels of human engagement. These simulations act as stand-ins for real world scenarios, but they provide useful insights into the ways in which adaptive, human-focused approaches can be more effective than rigid or entirely automated schemes.The three objectives of this study are three folds: to contribute to the theorizing of Industry 5.0 in harmonizing human agency with CPPS; to provide practical evidence in reducing compliance risk through adaptive planning as well as encouraging workforce engagement; and to provide policy directions in harmonizing regulation driven manufacturing with emergent digital manufacturing technology. The paper, in the process, contributes in an original manner through the combination of three seldom intersected facets of human-centric design, adaptive planning, and regulation driven manufacturing. The findings highlight the transformative potential of Industry 5.0 when human skills as well as machine cognition are implemented in tandem in order to offer resilience, compliance, and sustainable value.

2. Literature Review

- The discussion of manufacturing revolution had long been guided by the trajectory of Industry 4.0, which emphasized automation, digital connectivity, and utilization of cyber-physical systems within production environments. Industry 4.0 demonstrated that combination of sensors, cloud computing, and real-time analysis would increase efficiency and transparency across value chains. However, the same emphasis on autonomy and machine-based optimization spawned paradox: systems became more proficient in self-organization but increasingly more resistant to sudden perturbations in regulation, ethical concerns, or disruption that relied on human judgment. As the global networks of supply continued to become more turbulent (particularly in the high-value, high-risk industries such as pharmaceuticals and aerospace) the limitations of the industry 4.0 paradigm became more pronounced. Such setting laid the foundation for the emergence of Industry 5.0, the vision that centers re-integration of human creativity, sustainability goals, and resilience as the foundation of technical development. Industry 5.0 redefines smart production as no longer the system that is driven mainly by machines but the collaboration of people with smart technologies [5].Central to both Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 is the concept of Cyber-Physical Production Systems (CPPS). CPPS bring together physical assets, governing systems, infrastructures of communication, and computational intelligence in the cause of building an integrated production environment. CPPS enables smooth data flows from machines through digital platforms that support predictive maintenance, optimization of processes, and allocation of resources in near real time. During the Industry 4.0 phase, the CPPS were mainly implemented in the quest to streamline automation, provide reduced downtime, and optimize operations in lean terms. Nevertheless, from the perspective of Industry 5.0, CPPS are re-visualized as socio-technical ecosystems in which the human worker is no longer merely the dispassionate observer but an integral participant. Researchers increasingly emphasize that CPPS should transition from being efficient tools to generators of resilience and ethical value creation. Such transition requires architecture that brings the human decision making together with the machine analytics, as opposed to compartmentalizing the two [1] [6].Human-focused design principles provide the intellectual connection from CPPS to Industry 5.0. Classic system design usually stressed the necessity of ergonomic and occupational protection, that human operators ought to be in a position to interact with machines with no bodily injury and no excessive cognitive stress. Industry 5.0 extends this and demands systems that respect human autonomy, creativity, and well-being. From this angle, digital twins, augmented reality (AR), and explainable AI are enablers of productive efficiency but also instruments that provide the worker with the means to take well-informed choices. Ergonomics and human-computer interaction research highlight that if people are introduced as co-designers of the procedure, the possibilities of system acceptability, trust in automation, and long-term compliance grow substantially. Such is aligned with the requirements of regulated industries, whose sectors place inestimable value on human accountability [5].The needs of regulated manufacturing, particularly in pharmaceuticals, health care devices, aerospace, etc., introduce added complexities while bringing sophisticated production systems into use. The regulations stipulated by the FDA, EMA, and other like authorities target product safety, quality, and reliability assurance. They insist upon traceability, meticulous documentation, and qualified processes, which in themselves tend to solidify planning and slow responsiveness. Classic enterprise planning systems, founded mainly on deterministic schedules and fixed plans, inevitably fail against such constraints. Adaptive planning, with flexibility through the means of coping with fluctuations in demand, interruptions in the production cycle, or acts of regulation unforeseen, is thought an exhilarating solution. Digital twins that may simulate the end of compliance virtually before physical implementation represent one means of merging adaptability with regulative sureness. However, there is scant practical incorporation of adaptive planning in regulated CPPS environments [7] [8].Newest work began to frame the shortcomings of prevailing strategies. Highly automated CPPS, while effective, have demonstrated to engender compliance risk when there is the necessity for subtle human nuance in responding to changes in regulation. Highly human-centric systems, in contrast, are constantly plagued with inefficiency and inconsistency. A hybrid solution—in which the human remains in the decision loop with the assistance from smart CPPS that have the capacity to model diverse compliant scenarios—is ostensibly more durable. However, direct literature that addresses this convergence is in short supply. Most of the published literature splits the technical potential of CPPS, the ethical program of Industry 5.0, or the challenges of regulated manufacture but rarely integrates the three aspects [2] [9].The review therefore identifies an explicit gap in the research: no comprehensive works have investigated how human-centric CPPS can execute adaptive planning within the constraints of stringent regulation. Most published works are conceptual, with no validation, or single-technology based, with no overall human-machine regulation framework. Further, while simulations and digital twins are constantly referred to as prospective means, only a small number of papers have systematically employed them in order to evaluate compliance-driven adaptive planning. Overcoming the gap is essential in order to take both theorized understanding and practical application forward with Industry 5.0, so that regulated industries may benefit from the flexibility and resilience promised through future production systems.

3. Conceptual Framework

- The incorporation of human-centric values within Cyber-Physical Production Systems (CPPS) is the paradigmatic turning point in the development of manufacturing within the industry 5.0 framework. Whilst Industry 4.0 aimed at maximizing efficiency and connectivity, the latter tended to relegate human functions to the role of supervision or reactivity. The concept of Industry 5.0 recasts this dynamic with the repositioning of the human at the core of the socio-technical system, with the redefinition of CPPS as the collaborative system in which human judgement, creativity, and ethical accountability blend with the intelligence of technology. The conceptual architecture of human-centric CPPS should therefore instantiate human decision-making as central and integral to adaptive planning processes, rather than marginal, particularly in scenarios in which compliance and regulation constitute narrow boundaries within which operations take place.Central to this framework is the recognition that adaptive planning is more than a technical problem of rescheduling or optimization but rather is a socio-technical challenge that requires negotiation across algorithmic possibilities and requirements of regulation. Optimized-for-efficiency classic planning engines cannot usually meet the interpretative dimension of regulation, wherein the knowledge of context and human judgment is ineliminable. The framework offered, integrates digital twins, artificial intelligence, and compliance-based knowledge bases with human-in-the-loop regulation countermeasures. Planning algorithms under such a system generate many scenarios, with each scenario reflecting the regulation and operational consequences of various choices, while human operators evaluate, validate, and direct final execution. The strategy realizes the best of both worlds: machines are well suited to high-capacity data processing and scenario forecasting, while people contribute contextual awareness, ethical review, and adaptability to unforeseen perturbations.The system architecture of an end-to-end human-centric CPPS in the regulated manufacturing context can be visualized as a multilevel system whereby regulatory intelligence is organically ingrained from the onset. At the input level, production requirements, regulative requirements, and real-time shop-floor data are constantly ingested into the system. These are fed into a processing level wherein simulation engines powered by digital twins simulate prospective planning changes due to interruptions such as changes in demand, equipment breakdowns, or regulative audits. Notably, such digital proxies are dynamic, both mirroring the physical status of the production system as well as the manner in which the production system is regulated. The results of such simulations are then presented to human decision-makers in the forms of natural visualization devices such as augmented reality dashboards or explainable AI interfaces that offer clear study of the compliance risk vis-vis the working trade-offs.Human activities in this paradigm extend beyond the function of supervision. Operators and planners are renamed co-architects of adaptive plans. Through interaction with simulation outputs, workers can investigate regulatory what-ifs, evaluate the resilience of plans submitted, and contribute domain expertise that cannot be algorithmically represented. For example, in pharmaceutical production, the planner will be in a position to observe the consequence of batch release delays that would be undetected by an optimization engine driven under deterministic rules. Again, in aerospace assembly, the worker will be in a position to recognize subtle quality issues that are undetected by automated inspection apparatus and contribute corrective insight in the digital twin environment. These interactions are no afterthought but are integral in the framework as mandated checkpoints at which human judgment sets the course of adaptive planning.The conceptual framework also identifies the ethical and social dimension of Industry 5.0. Compliance in regulated areas is not just the technical guarantee of quality but is rather the societal consensus that secures public protection and trust. The incorporation of human-centric values in CPPS therefore makes the adaptive planning procedures responsible and ethically fair. The framework prevents overdependency on black-box algorithms and possibilities of compliance violations based on purely machine-driven planning by providing human operators with decision support rather than automated prescriptions. The strategy also creates the possibility of constructing confidence among regulators and laborers that high-level technologies are being implemented as supplements of their efficiency rather than in lieu of human responsibility.Ultimately, this framework proposes an adaptive planning hybrid model with both machine and human intelligence as mutually supportive. They provide the width of analysis, speed, and accuracy that is required in order to mimic complex environments of regulation, and they provide interpretability, contextual information, and ethical reasoning. Both provide an adaptive system that is liable to maintain compliance within variable and dynamic conditions. Through the codification of this collaboration within an integral CPPS framework, Industry 5.0 is in a position to deliver on its promise of an efficient production system but one that is sustainable as well, ethical, and adaptable in the presence of the distinctive requirements of the regulated factory.

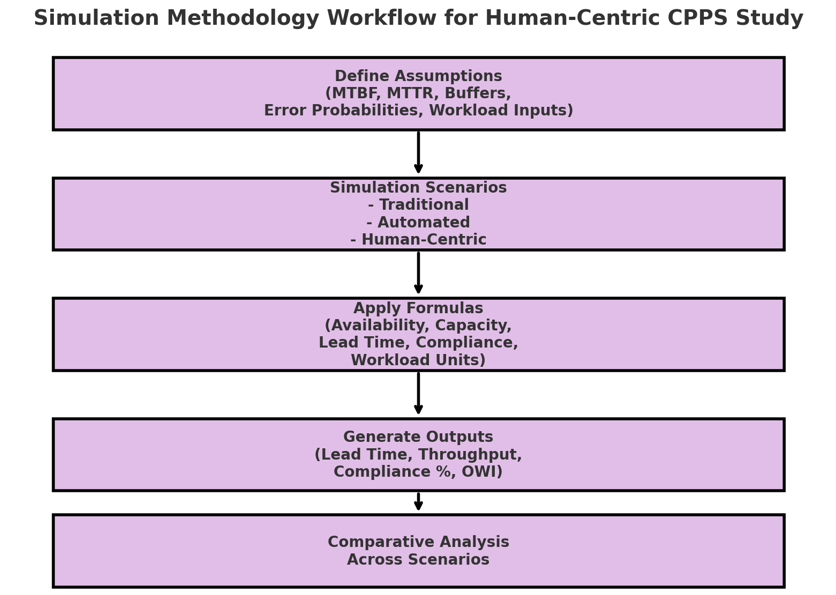

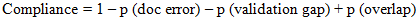

4. Methodology (Simulated Study Approach)

- Since the regulated manufacturing industries are characterized by access and secrecy limitations, the application of real-world datasets is often infeasible. Therefore, this study applies simulation-based research methodology in examining the feasibility and consequences of harmonizing human-centric CPPS with adaptive planning processes. The application of simulation as methodology is particularly fitting because the intricate systems that constitute the socio-technologies of regulation and production can be simulated under controlled experimentation while ensuring that the regulation limitations, human interaction, and technology interaction are effectively portrayed in the simulated world. Under the simulation of various scenarios of production and regulation, the methodology enables a conceptual but evidence-based examination of how human-centric Industry 5.0 systems would be in comparison with the conventional or automated planning approaches.The first step in constructing the simulated study is the development of the digital twin environment that is capable of reflecting the physical as well as the regulatory dimension of a production system. Unlike conventional simulation models that only highlight the use of machines or process flow, the digital twin in the simulated study is established in such a manner that it embodies requirements of traceability, measures of compliance, as well as document practices. For instance, in the pharmaceutical system of production, the twin encompasses not only material movement as well as information from the machines but also batch histories, audit trails, as well as the FDA-imposed quality checkpoints. Similarly, in the aerospace example, the twin embodies safety-critical histories of parts, needs of inspection, as well as certification milestones. Such inclusions mean that the simulated planning process is tested against the same drives of compliance that have materialized in the physical world of regulated manufacturing.The research design also allows for the inclusion of human agency in the simulation. For this reason, the study identifies human-in-the-loop modules that are the nodes of decision in which the planners or the operators would intervene. These are informed by well-established principles of ergonomics, exploration of human–machine interaction, as well as structures of regulatory decision taking. For example, in the course of a simulated regulatory audit, the system will yield many adaptive planning scenarios, but final choice will be mediated by a virtual human agent that is programmed to embody compliance intelligence and ethical judgment. This creates the possibility of examining how human judgment changes the optimized solution of the machines, and whether the intervention yields better resilience and regulation of outcomes.Simulation environment developed through AnyLogic 8.8.5 Professional due to its hybridity between hybrid discrete-event and agent-based modeling. Digital twin modules were organized to simulate the physical–digital interconnection of cyber-physical systems through the integration of parameterized process streams, compliance check points, and human-in-the-loop agents. Each module encapsulated a functional layer—production scheduler, regulatory audit, and operator decision nodes—interlinked through shared variables and event triggers. Model architecture took on the style of modular logic where the effect of changes in compliance parameters or human timing decisions could be added as distinct experiments. Such an organization guarantees the reproducibility of results by other users with similar simulation suites, i.e., Tecnomatix Plant Simulation.A comparison framework underpins the simulation experiments. Three conceptual scenarios are simulated: traditional planning strategy with limited human intervention, automated CPPS with no human intervention, and Industry 5.0-based human-focused CPPS. Each scenario is presented with the same disruptors, such as raw material demand fluctuations, mechanical failures, or routine regulator inspection events. Comparing scenario outputs enables the simulation to uncover how adaptive planning strategies differ when human agency is systemically included. The outputs are compared using critical performance measures: disruption resilience, compliance adherence, operator workload, and system-wide efficiency. These measures are informed but not derived from empirical observations of case applications, but from established system engineering standards, regulatory compliance work, and organizational resilience research.The research is based on conceptual implementation using well-proven simulation platforms that can handle cyber-physical modeling, like AnyLogic or Siemens Tecnomatix, although the latter is not the subject of this paper. The focus is instead on illustrating the possibility of the methodology in aligning human-focused CPPS with adaptive planning in regulated sectors. For the purpose of rigor, assumptions underlying the simulations are well-articulated. For instance, the operator's decision time is assumed to be based on average response time from the industry, and the violation of compliance is simulated as random events triggered when planning choices diverge from the standards of regulation. The use of sensitivity analysis is built in to check the result's robustness under conditions of variable stringency levels in regulation and levels of operator engagement.Under this simulated framework, the research finds equilibrium in between conceptual examination and practical insight. The research is allowed to investigate scenarios that would be costly, hazardous, or unfeasible in actual production environments but be faithful to the regulation and human factors that typify the problem space. The structure in simulation also forecloses the results from being unidimensional technical but holistically addressing the socio-technical, regulative, and ethical challenges presented in Industry 5.0. Through this, the methodology is in a position to offer an academically stringent foundation upon which one may construct the theories while at the same time offer practical insights that may be utilized in thinking through the future integration in regulated manufacture of CPPS.To put the simulation in perspective, imagine an abstract case from the pharmaceutical batch production line where FDA regulations apply. Here, an upset in one temperature-controlled stage of mixing initiates the compliance audit event within the digital twin. Multiple alternative planning paths—for instance, reselling operators to manually inspect, changing the batch hold time, or starting the revalidation process—are calculated to determine the effect on production continuity and also on conformity to regulation. A human-in-the-loop agent studies these simulated results and chooses the plan finding the balance between compliance integrity and lowest production delay. Likewise, on an aerospace assembly line, the model can simulate the rescheduling of inspection tasks on the issuance of a non-conformance report and demonstrate how adaptive human review frustrates the violation of compliance without compromising assembly flow. Such abstract examples prove how the structure simulated can be translated to the real regulated worlds to provide both operational resilience and strict regulation conformity.

| Figure 1. Simulation methodology workflow for evaluating human-centric CPPS in Industry 5.0 |

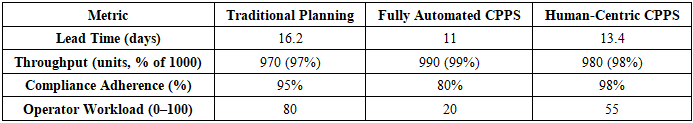

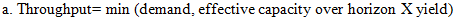

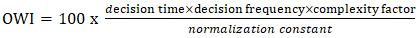

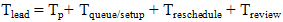

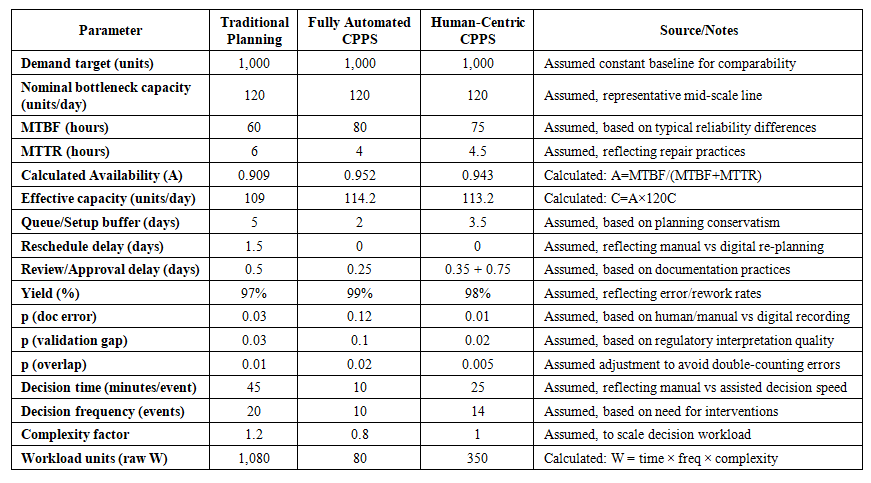

5. Findings from Simulated Scenarios

- The simulated experiment provided evident comparisons among conventional planning systems, automated CPPS, and the new human-based CPPS under the Industry 5.0 framework. Each scenario, while simulated in the same production and regulating environment, presented differentiated capabilities in efficiency, compliance, and flexibility. These results, while of conceptual nature, provide convincing evidence of the value in the integration of human agency in high-end cyber-physical systems in regulated manufacturing.We consider it as one batch (or fixed horizon) with demand target of 1,000 units in the three-stage flow line, viz., the prep (S1), main processing (S2), finishing/QC (S3) stages. The times are assumed but in sync with each other.• Nominal single-line capacity (no disruption):a. S1: 120 units/dayb. S2: 120 units/dayc. S3: 120 units/dayd. Bottleneck capacity = 120 units/day• Baseline lead time components (if nothing goes wrong):a. Queue + setup time in S1–S3 = 3 daysb. Processing window at bottleneck for 1,000 units = 1000/120 = 8.33 dayc. Baseline internal reviews/doc signing = 0.5 dayd. Baseline lead time (perfect world) = 3 + 8.33 +0.5 = 11.83 days (rounded to 12.0 days)• Uptime model (used to perturb capacity):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

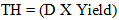

| Table 1. Simulation Input Parameters for Three Scenarios |

|

| Figure 2. Comparative results of the three simulated planning scenarios |

6. Discussion

- The findings from the simulated scenarios bring out the transformation potential of human-centric CPPS in tandem with the grander picture of Industry 5.0. While Industry 4.0 stressed automation and connectivity, the findings reported here reflect that in the highly regulated manufacturing scenario, such assets fall short. The fully automated system realized the efficiency but failed across the board in meeting compliance, reflecting that interpretative capacity in regulation is something in which the machine intelligence falls short of the human. The human-centric CPPS system bridged this gap through flexibility that was at no cost in terms of compliance, in effect instantiating the main argument of Industry 5.0: collaboration among human and intelligent systems as opposed to displacement. Recent research shows that combining deep learning with reinforcement learning helps systems adapt better and make more accurate decisions in changing environments [10].Theoretically, this work contributes to the literature in socio-technical systems in manufacturing by strictly connecting human-centric design with adaptive planning under regulation. Existing CPPS scholarships often give up the measure of efficiency as the only measure of success in favor of compliance and human well-being. The present work shifts the conversation in that compliance must be taken as the first-order design criterion in regulated areas, while human engagement is at the fore in the working out and interpretation of regulation in variable scenarios. Through the introduction of human judgment in the feedback loops of CPPS, the framework goes beyond the logic of optimization from Industry 4.0 and demonstrates how the principles of Industry 5.0 may be instantiated in practical schemes of planning.In practice, the study offers lessons on how highly regulated sectors such as pharmaceuticals, aerospace, and medical devices can move towards more resilient patterns of production. In pharmaceuticals, for instance, the adaptive planning using digital twins can potentially allow producers to re-schedule batch production plans due to spontaneous audit requests while keeping the same compliance with FDA. Aerospace producers could similarly use human-in-the-loop digital twins to manage traceability of safety-critical components while being effective in assembly lines. Medical device producers that continue getting design refinements based on clinical requirements could use human-centric CPPS to model the regulatory what-if scenarios before they undertake costly physical changes. These scenarios illustrate that the advantage from using human-centric CPPS is not through the optimization of short-term throughput but through long-term resilience, something that is increasingly believed critical in meeting public safety and trust needs.Policy and governance considerations are no less significant. International regulators are only now becoming cognizant of the possible role of advanced digital tools in the attainment of compliance, but frameworks remain fragmented and often lag behind in comparison with capabilities. The conceptual results of this study suggest that coordinated frameworks that specifically account for digital twins, AI-driven decision support, and human-in-the-loop architecture may yield more consistent compliance profiles across sectors and jurisdictions. Moreover, the incorporation of human judgment within planning frameworks may yield confidence in technology adoption among regulators that it is not undermining accountability but supporting it. Such policy convergence is critical in helping spearhead the diffusion of Industry 5.0 technologies while maintaining public confidence in regulated products.Despite such opportunities, the report's findings also identify underlying risks and challenges. Security of data is a prime issue: incorporation of regulatory records and compliance procedures in the CPPS enhances the risk of cyberattacks, which would have catastrophic effects in regulated sectors. In controlled manufacturing where audit trails, certification information, and quality records are electronically attached to production assets, the security of compliance data is critical. Unapproved access or data tampering can compromise not only regulatory integrity but also organizational trust. Accordingly, the architecture of human-oriented CPPS has to comprise encrypted communication links, control-access hierarchies, and tamper-friendly logging components. Trust also demands transparency on the part of AI modules on the way compliance data is processed and stored to ensure that decisions are auditable and explainable to regulators and human operators alike. Over-reliance on AI also poses the risk of algorithmic bias or misinterpretation of unclear standards, raising ethical concerns over accountability in the decision-making. Again, resistance in the workforce cannot be overemphasized. Even when the human-centric orientation is emphasized, the incorporation of the latest digital systems would create concerns over redundancy or deskilling. Effective implementation would thus be required that would not only be based on technological innovation but would also demand organizational change management, worker training, and clear communications building trust among the stakeholders.The opportunities far exceed the challenges. Human-centric CPPS envision a future where compliance, resilience, and human values no longer compete with efficiency but become part of the design of the manufacturing systems. Through convergence with the circular economy and sustainability goals, such systems can also facilitate broader societal objectives such as carbon reduction and responsible use of the earth's assets. Industry 5.0 thus views manufacturing as more than the economic engine but as the part of the socio-technical system that aligns technological potential with human responsibility. The conceptual findings of this research outline one possible future path toward realizing this vision even in the high-stakes environment of regulated manufacturing.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

- The study was focused on exploring how human-centric Cyber-Physical Production Systems (CPPS) can be applied within Industry 5.0 environments in order to support adaptable planning in controlled production environments. By utilizing the simulation-based research methodology, the paper derived and evaluated an initial conceptual framework that compared standard planning, fully automated CPPS, and hybrid human-centric CPPS. The findings systematically demonstrated that while automation realizes efficiency advantages and standard approaches preserve compliance, only the human-centric concept is able to adequately balance both facets in an equitable and sustainable way. The finding supports the fundamental principle of Industry 5.0—that the most sustainable and ethically acceptable production systems are the ones in which smart machines and people coexist as equal partners rather than mutual replacements.The originality of this work is in three areas. Theoretically, the work extends the thinking in socio-technical systems through the positioning of human judgment and compliance interpretation as central elements in adaptive planning, in place of afterthoughts or verifications from the periphery. Practically, the work contributes lessons transferable in regulated spaces such as pharmaceuticals, aerospace, and medical devices, in highlighting how digital twins, AI-driven planning tools, and human-in-the-loop schemes in decision-making can be choreographed in efforts aimed at achieving efficiency as well as compliance. Policymakers from the study learn the value of harmonized schemes in regulation that intentionally recognize and encourage the use of human-centric CPPS, digital twins, and decision support systems based on AI as tools that increase, not decrease, compliance assurance.At the same time, the study also identifies its limitations. The findings rely on conceptual simulations rather than empirical data from the industry, limiting generalizability. Despite being carefully constructed as highly simplified approximations of real regulatory conditions, the simulations could not capture the full dynamism of organizational dynamics, workforce culture, or market pressures that underline genuine manufacturing systems. Additionally, the human-in-the-loop models employed in the simulations are simplified approximations of decision-making, rather than the nuanced and contextually sensitive reasoning that operators bring in practice. These limitations don't invalidate but instead recommend empirical verification in future studies.The future will see this framework enriched through pilot deployments in live production activities, particularly in areas where regulatory compliance is required. The interaction among the academia, the industry, and the regulating bodies will be instrumental in subjecting the human-centric CPPS under practical use conditions and in refining the use of digital twins in recreating compliance results. The second area is how new technology such as the blockchain, explainable AI, and extended reality (XR) could be integrated within the framework in raising the transparency levels, fostering trust, as well as empowering the operators. Longitudinal studies that concentrate on how workforce training, the organizational culture, and the change management practices influence the use of human-centric CPPS and how they perform will be no less imperative.In short, this study accentuates that the future of regulated manufacturing is no longer in choose versus machines but in cultivating systems in which both contribute their strengths. Industry 5.0 delivers an efficient, resilient, sustainable, and essentially human-centric vision of manufacturing. Through simulated outputs illustrating how human-centric CPPS can provide adaptive planning with no compromise in terms of compliance, this work provides both the theoretical foundation and the practical advice called for of sectors subject to the stringent demands of regulation in the digital age. The framework presented here should provide the foundation upon which future work will be based, both shifting academic scholarship and industrial development toward the future in which technology enhances rather than diminishes human value in manufacturing.

Conflicts of Interest

- On behalf of corresponding author, there’s no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

- The authors did not receive any type of financial or non-financial support from any organization for the submitted work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- All authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML