Kelvin Bwalya, Simon Tembo

School of Engineering, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Correspondence to: Kelvin Bwalya, School of Engineering, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

This study investigates the application of Network Access Control (NAC) mechanisms supported by machine learning to enhance the security of Internet of Things (IoT) environments in Zambia’s digital transformation. Using the NetSim network simulator, two scenarios were constructed to generate and analyse synthetic network traffic. Scenario 1 modelled a baseline environment consisting solely of known, authorized IoT devices. Scenario 2 introduced a suspected malicious device with altered throughput designed to induce network distress. Comparative analysis of the two scenarios revealed that the malicious device caused degradation in overall network performance, underscoring the risks of unchecked device access. Throughput analysis, alongside detailed media access control (MAC) and physical (PHY) layer payload data, was systematically collected to capture device communication behaviours. These features were structured into datasets used to train a machine learning model capable of automatically detecting anomalous traffic patterns. The model focuses on identifying malicious devices by analysing abnormal packet influx, enabling dynamic and adaptive NAC enforcement. The outcomes demonstrate the potential for simulation-driven approaches to support both automatic device identification and regulatory type approval processes. By integrating such models into Zambia’s ICT security frameworks, authorities and regulatory bodies can strengthen oversight, ensure that only compliant devices are approved for network integration, and safeguard national digital infrastructures against evolving cyber threats.

Keywords:

Internet of Things, Network Access Control, Machine Learning, Throughput, Internet Exchange Point

Cite this paper: Kelvin Bwalya, Simon Tembo, A Study on Adaptive Network Access Control for Secure IoT Integration in Zambia, Computer Science and Engineering, Vol. 15 No. 6, 2025, pp. 129-135. doi: 10.5923/j.computer.20251506.01.

1. Introduction

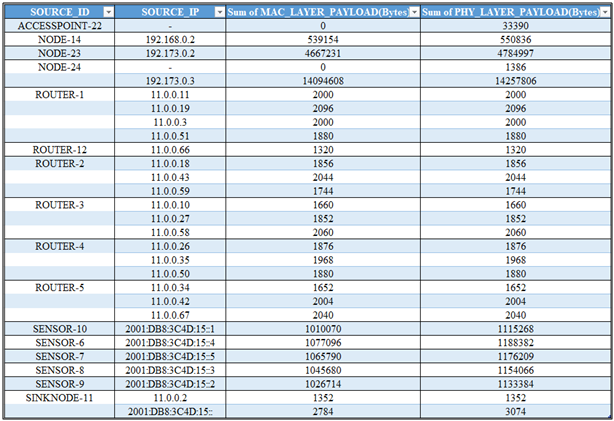

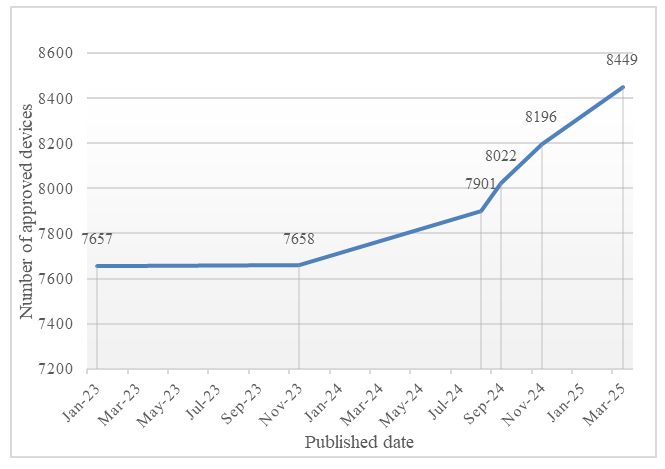

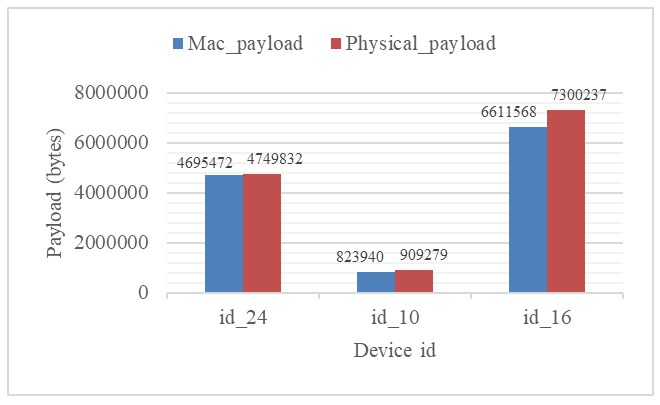

Digital transformation refers to the adoption of emerging technologies such as mobile platforms, analytics, embedded systems, and social media to drive business improvements, enhance service delivery, and create new business models [1]. At the core of this transformation is the Internet of Things (IoT), defined as a global infrastructure that interconnects physical and virtual objects through interoperable communication technologies. IoT enables advanced services and innovation by digitalizing products and processes [2].Globally, digital transformation has emerged as a disruptive force across industries, including telecommunications, with IoT identified as a primary driver of this shift. The IoT market, valued at USD 478.36 billion in 2022, is projected to expand to USD 2,465.26 billion by 2029, underscoring its accelerating role in reshaping economies [3]. Its growth is tied to its capacity to create business opportunities, optimize operations, reduce costs, and improve efficiency. Moreover, the number of IoT devices worldwide is expected to approach 30 billion by 2030, reflecting its central role in enabling digital innovation and transformation. This growth trend, drawn from [4], is further illustrated in Figure 1, which presents the forecasted increase in connected devices over time. | Figure 1. IoT vs non IoT active device connections worldwide from 2010 to 2025 |

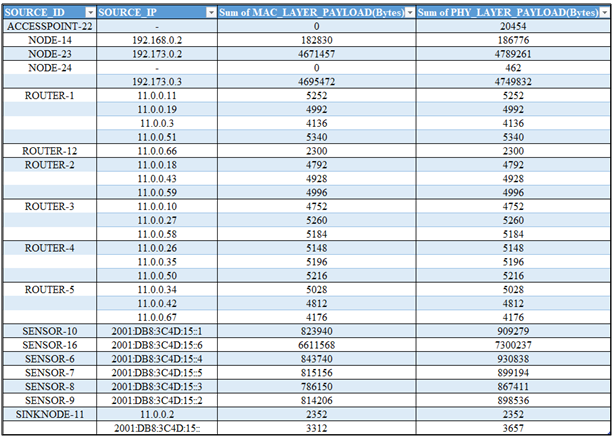

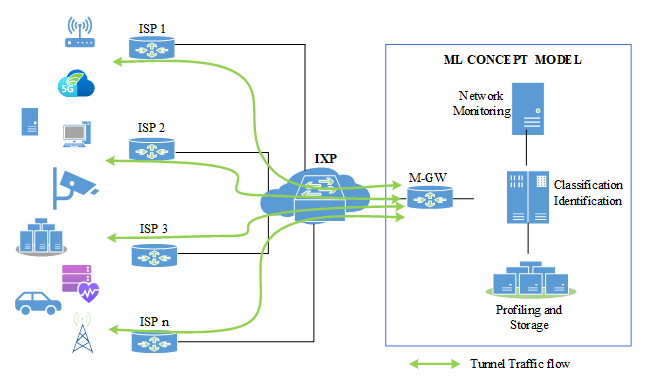

Zambia has continued to record steady progress in the adoption of emerging digital technologies, a process that is broadly captured under the concept of digital transformation. This transformation refers to the systematic integration of digital tools and innovations into business processes and economic activities, fostering greater efficiency, service delivery, and innovation across sectors [5].As part of this trajectory, type approval of internet-connected equipment has demonstrated a gradual upward trend. Figure 2. Shows the number of recorded, approved device types increased modestly, between January 2023 and March 2025, reflecting a static but positive progression. | Figure 2. Devices type approval, Source [ZICTA website Publications] |

With billions of interconnected devices continuously collecting, transmitting, and exchanging data, concerns around data security and privacy have intensified, particularly considering the global escalation of cybercrime [3]. Addressing these challenges in the Internet of Things (IoT) ecosystem requires a comprehensive security approach that incorporates strong authentication protocols, routine firmware updates, encryption of communications, and continuous monitoring to detect anomalous network activities.Within this landscape, Network Access Control (NAC) emerges as a critical mechanism. NAC enables the automatic identification, profiling, and inventory management of connected network devices [6]. NAC strengthens oversight, supports compliance with security policies, and provides a foundational layer of defence against malicious or non-compliant devices within increasingly complex IoT environments.

2. Literature Review

Existing scholarly contributions [1], [3], related publications [5], and the National Digital Transformation Strategy (2023–2027) consistently emphasize that the widespread adoption of IoT generates both opportunities for innovation and significant risks around privacy, security, and regulatory compliance [7]. [8] contributed and understanding that most attacks on IoT devices can be performed at various network levels. These works acknowledge the critical need to secure IoT ecosystems but often stop short of proposing practical, context-specific mechanisms for addressing device-level threats.Implementing IoT within the framework of digital transformation introduces multiple challenges, particularly in security and data privacy. These challenges pose a risk to the safety and reliability of IoT services, potentially affecting their availability, confidentiality, and data integrity [9]. The discovery and detection of Internet of Things (IoT) devices are essential components of managing IoT ecosystems, especially in terms of security and network management.[10] illustrates that real-time detection of IoT devices is often the only effective line of defence against targeted attacks, as conventional tools struggle to identify and block malicious traffic generated by compromised devices. Similarly, the author [11] highlights the lack of visibility in internet connected devices environments as a critical vulnerability, noting that without robust mechanisms for device discovery and monitoring, security architectures remain incomplete. These findings converge on the conclusion that networks require device-level visibility, continuous monitoring, and automated classification as foundational elements of security. The reviewed studies justify the need for this research, which aims to develop and test a machine learning-driven NAC model capable of automatically detecting, classifying, and regulating network devices.According to [12], traditional methods of securing IoT typically rely on cryptographic authentication and verification. The diversity and dynamic nature of IoT environments make it hard to apply uniform cryptographic measures. This establishes the need for non-cryptographic detection methods, which instead rely on traffic features, behavioural analysis, and anomaly detection. However, such approaches are underexplored and remain challenging due to the heterogeneity of IoT devices and services. Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have emerged as powerful alternatives, offering the ability to automatically extract distinctive features from traffic data and to classify devices with greater accuracy. The authors of [13] further confirm that ML techniques have advanced significantly in cyber threat detection and are now central to strengthening IoT security frameworks. These insights validate the adoption of an ML-driven approach for IoT device detection and classification in this study.For the Zambian context, where IoT adoption is accelerating across critical sectors, but regulatory oversight remains limited, an ML-based NAC model offers clear advantages.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach and Design

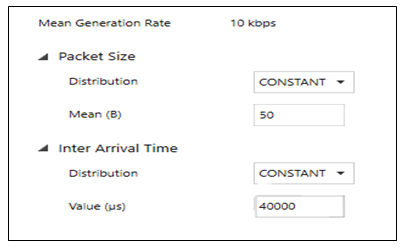

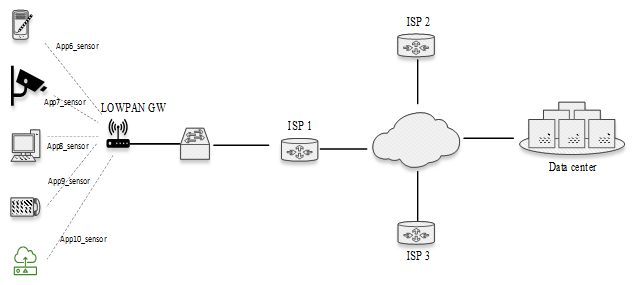

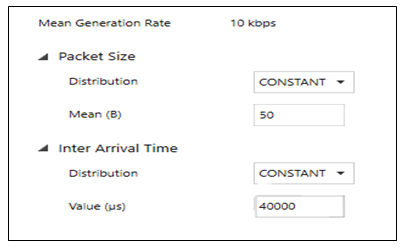

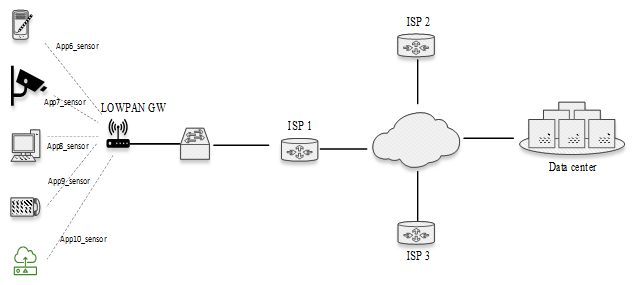

This study employs a data-driven quantitative approach, and a systematic literature review was conducted to gather, evaluate, and synthesize existing scholarly related works.To conduct this study, NETSIM network simulator software was used to replicate real-world networking environments and generate synthetic traffic data representative of IoT device communications. The simulator captures a range of parameters, including IP addresses, throughput, physical layer payloads, Media access control (MAC), and delays, thereby providing a reflection of device behaviour in live network conditions. During each simulation run, NetSim produced detailed packet-level logs which were subsequently exported into structured datasets for analysis. Two scenarios were constructed to evaluate network performance.Scenario 1 with topology setup Figure 3 was designed to establish a controlled baseline of sensor-generated traffic for performance evaluation. In this setup, five sensor applications (App6_Sensor_app through App10_Sensor_app) were configured to transmit with a fixed packet size of 50 bytes while maintaining an average throughput of 10 kbps per sensor. In NetSim, configuring the desired throughput requires determining the time interval between packet transmissions, based on the specified throughput rate and packet size. This ensures that data is transmitted at a controlled rate consistent with the simulation objectives. | Figure 3. App6_Sensor_app through App10_Sensor_app configuration |

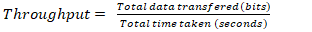

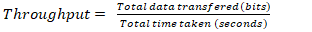

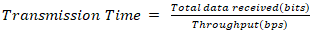

Throughput is the rate of successful data transfer per unit time: | (1) |

Rearranging to find the time interval: | (2) |

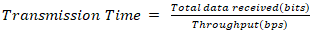

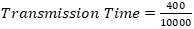

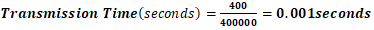

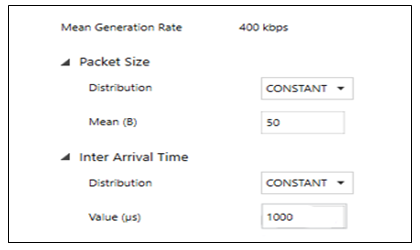

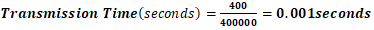

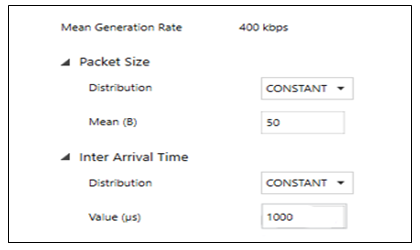

Desired throughput = 10kbps =10000 bits per secondPacket size = 50 bytes = 400 bits = 0.04 seconds In NetSim, packet transmission timing is represented in microseconds (µs) rather than in seconds or milliseconds. Consequently, to achieve the desired throughput configuration, the corresponding inter-packet arrival time value of 40,000 µs must be entered into the simulator settings as illustrated in Figure 2.This configuration ensured that each device contributed a predictable and uniform traffic flow, resulting in a combined offered load of 50 kbps across all five sensors. Scenario 1 provided a stable baseline environment that served as the benchmark for assessing the impact of additional or malicious traffic, enabling comparative analysis of subsequent performance deviations introduced by abnormal network activity.Scenario 2, with topology setup Figure 4, extended the baseline by retaining the same configuration for the five sensors while introducing an additional application, App4, transmitting with the same packet size (50 bytes) but at a substantially higher throughput of 400 kbps. The purpose of this configuration was to simulate a rogue or malicious IoT device generating excessive traffic, thereby producing network distress.

= 0.04 seconds In NetSim, packet transmission timing is represented in microseconds (µs) rather than in seconds or milliseconds. Consequently, to achieve the desired throughput configuration, the corresponding inter-packet arrival time value of 40,000 µs must be entered into the simulator settings as illustrated in Figure 2.This configuration ensured that each device contributed a predictable and uniform traffic flow, resulting in a combined offered load of 50 kbps across all five sensors. Scenario 1 provided a stable baseline environment that served as the benchmark for assessing the impact of additional or malicious traffic, enabling comparative analysis of subsequent performance deviations introduced by abnormal network activity.Scenario 2, with topology setup Figure 4, extended the baseline by retaining the same configuration for the five sensors while introducing an additional application, App4, transmitting with the same packet size (50 bytes) but at a substantially higher throughput of 400 kbps. The purpose of this configuration was to simulate a rogue or malicious IoT device generating excessive traffic, thereby producing network distress.  | Figure 4. A baseline topology consisting of 5 sensors |

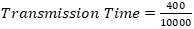

Similarly, the malicious device’s desired throughput is configured by determining its transmission time interval through the same calculation process and inputting the corresponding value in the configuration parameters to achieve the intended traffic load within the simulation environment. Desired throughput = 400kbps = 400000 bits per secondPacket size = 50 bytes = 400 bits 0.001second = 1000 µs. Figure 5 shows the malicious device App4 sensor configuration.

0.001second = 1000 µs. Figure 5 shows the malicious device App4 sensor configuration. | Figure 5. Malicious application configuration |

This stress-test environment enabled analysis of throughput degradation, packet-influx rates, and MAC/PHY-layer payload variations, providing empirical data for evaluating how the ML-based NAC model discriminates legitimate traffic from disruptive flows. | Figure 6. A topology with malicious device consisting of 6 sensors |

3.2. Data Analysis and Results

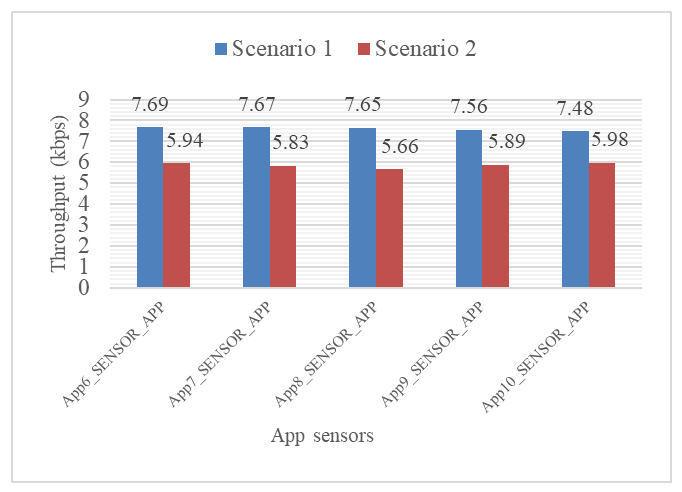

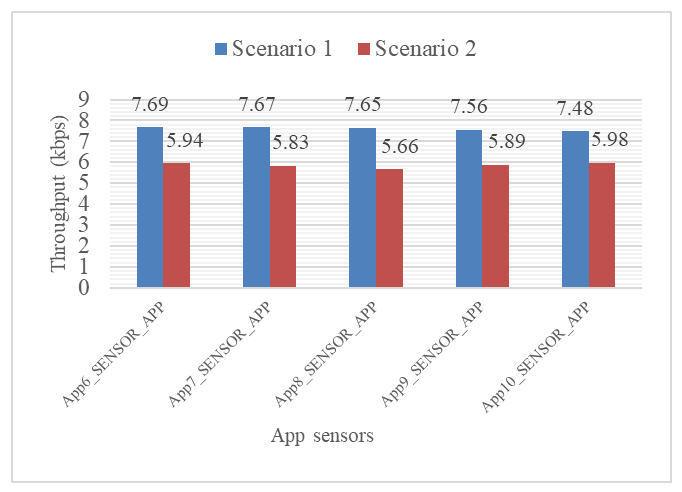

Results from scenario 1 were compared to those from scenario 2, while MAC and physical (PHY) layer data were further analysed to create datasets for the model. The analysis focuses on two key performance metrics throughput and MAC and PHY layer payloads for the sensors traffic. In the first scenario, the actual measured throughput values, were slightly below the configured rate ranging between 7.48 kbps and 7.69 kbps across the five applications. This variation can be attributed to inherent protocol and transmission overheads at different layers of the network stack. Factors such as inter-packet delays, buffer queuing, and propagation latency contribute to marginal throughput reductions relative to the theoretical transmission rate. Despite these minor discrepancies, the throughput values remain consistent across all five applications, demonstrating a uniform and stable traffic pattern representative of normal sensor network behaviour. In the second scenario, the measured results show that the throughput of legitimate sensor applications dropped significantly, averaging between 5.66 kbps and 5.98 kbps, while the malicious application achieved an effective throughput of approximately 49.28 kbps an indication that the malicious device dominated the available network bandwidth, causing congestion and resource contention that limited normal data transmission for legitimate sensors. Across the five sensor applications (App6–App10), the average measured throughput in Scenario 1 representing the baseline network condition was 7.61 kbps. When the malicious device (App4_DDoS_APP) was introduced in Scenario 2, the average throughput of the same legitimate sensors decreased to 5.86 kbps. The reduction indicates a throughput degradation of approximately 23% across legitimate sensor applications following the introduction of a high throughput malicious device (App4_DDoS_APP). Figure 7 shows the comparison of average throughput for sensor applications (App6–App10). | Figure 7. Comparison of average throughput for sensor applications (App6–App10) under normal conditions (Scenario 1) and malicious conditions (Scenario 2) |

3.2.1. ML-driven Network Access Control (NAC) model

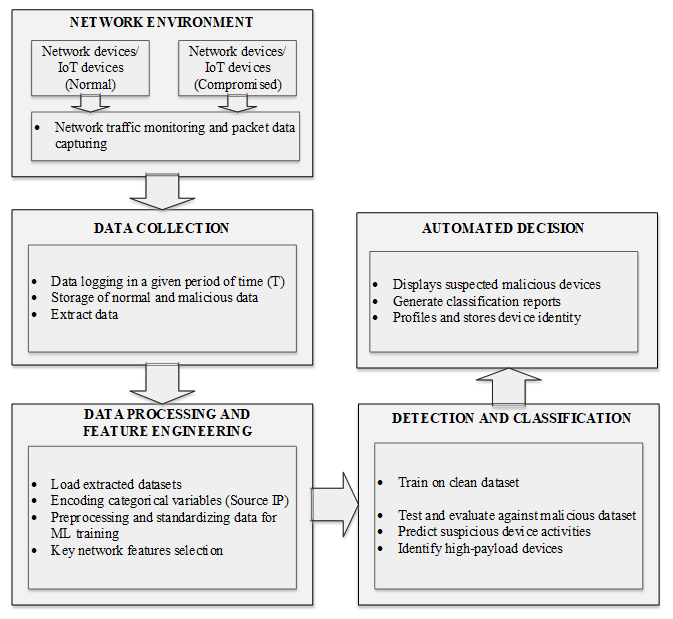

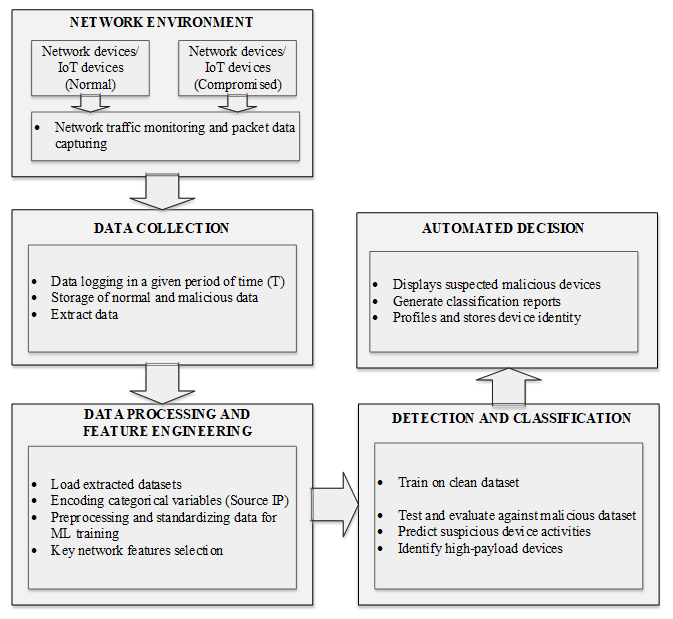

From both simulation scenarios, detailed network trace data were collected at the MAC (Medium Access Control) and Physical (PHY) layers. These layers provide critical low-level communication attributes that reflect real-time device behaviour and traffic characteristics within the simulated IoT environment. Different network monitoring tools, such as Wireshark or TCPDump, are used to capture live traffic data in real deployments. These tool intercept and analyse network traffic to extract key parameters such as packet size, source/destination IP addresses, and payload content.The extracted data were exported into structured datasets, combining features from both layers to form a comprehensive feature vector for machine learning analysis. These datasets were then labelled according to device type and behavior, clean (from Scenario 1) or malicious (from Scenario 2) to train and validate the proposed ML-driven Network Access Control (NAC) model. Figure 8. shows the Data flow for the development of the ML-driven Network Access Control (NAC) model showing stages from traffic simulation and feature extraction to model training and decision enforcement. | Figure 8. Data Flow for the ML-Based NAC Model |

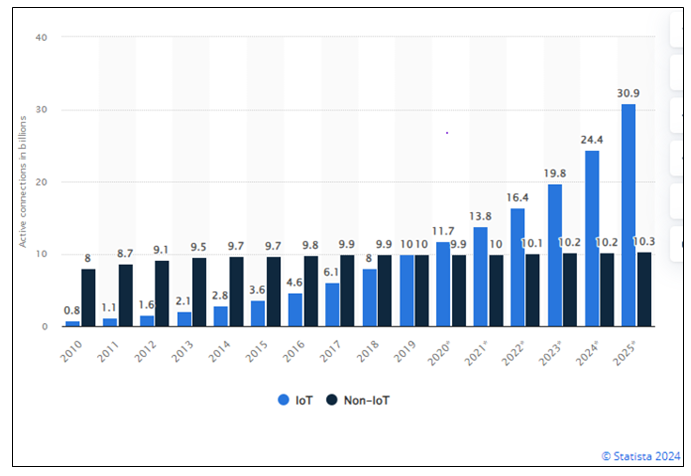

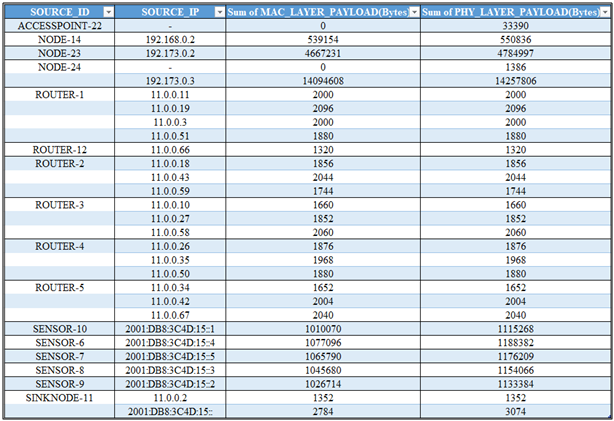

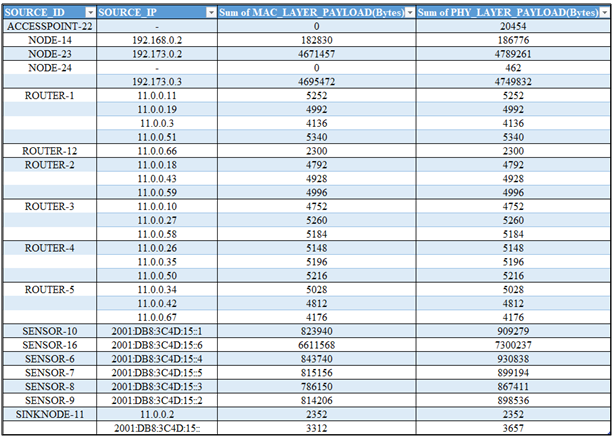

To demonstrate the logic and feasibility of the proposed machine-learning–driven Network Access Control (NAC) framework, a prototype model was implemented using Python. The model employs a supervised learning approach, specifically utilizing the Random Forest algorithm, for automatic identification and classification of network-connected devices. Supervised learning was selected because it relies on labelled training datasets, allowing the model to learn from known patterns of both legitimate and malicious network behaviour.Table 1. presents the clean dataset generated from the traffic extracts of Scenario 1, showing the MAC and Physical (PHY) layer payloads of all legitimate devices operating under normal network conditions. The dataset forms the baseline training data for the machine learning model.Table 1. Clean devices dataset

|

| |

|

Table 2. on the other hand, illustrates the dataset extract from Scenario 2, which includes an additional known malicious device (SENSOR - 16). This dataset captures both legitimate and abnormal traffic features, including irregular packet influx rates and altered MAC-layer transmission patterns. The inclusion of SENSOR – 16 introduces the behavioural deviations necessary to train the model to differentiate between clean and malicious devices.Table 2. Malicious device dataset

|

| |

|

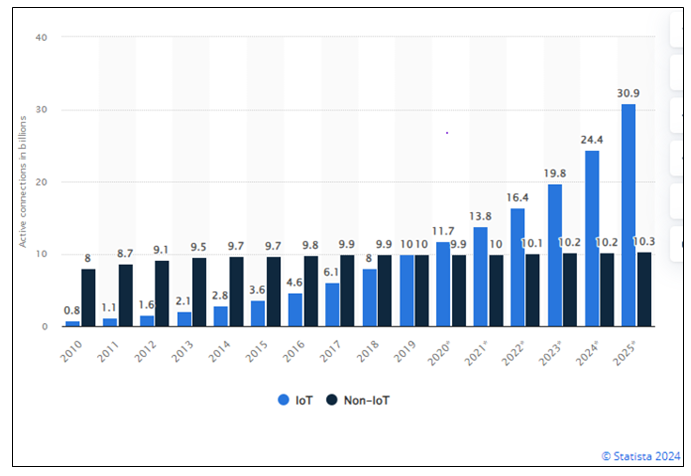

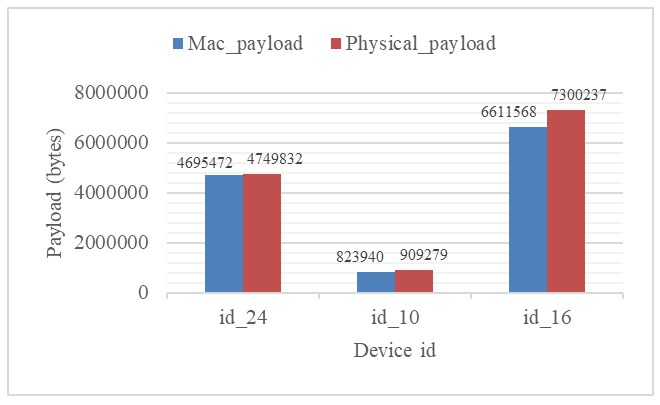

The Python-based machine learning model processes the pre-processed dataset containing network traffic features extracted from both scenarios. The Random Forest classifier is analyses the combined MAC and Physical layer payloads, continuously comparing each device’s traffic behaviour against the learned thresholds derived during the training phase. As illustrated in Figure 9, the model output presents a structured list of network devices, highlighting those flagged as potentially malicious based on abnormally high MAC and PHY layer payload values. Each output entry includes essential identifiers such as Device ID, Source IP address, MAC-layer payload size, and Physical-layer metrics, enabling detailed verification of anomalous traffic sources within the simulated IoT network. The Random Forest classifier effectively detected Device IDs 24, 10, and 16 as suspicious nodes due to their elevated payload statistics. Further dataset inspection revealed these correspond to network node-24, IoT sensor-10, and IoT sensor-16. Although the model achieved an overall classification accuracy of 91%, it correctly identified IoT sensor-16 as the deliberately configured malicious device, while Device IDs 24 and 10 were additionally flagged as potentially anomalous due to their high traffic variance. | Figure 9. Model output showing identified suspected malicious devices |

4. Discussions and Findings

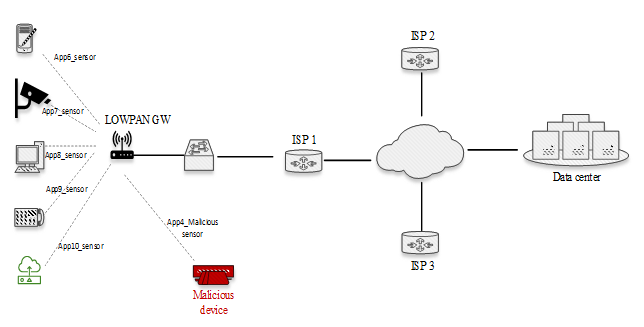

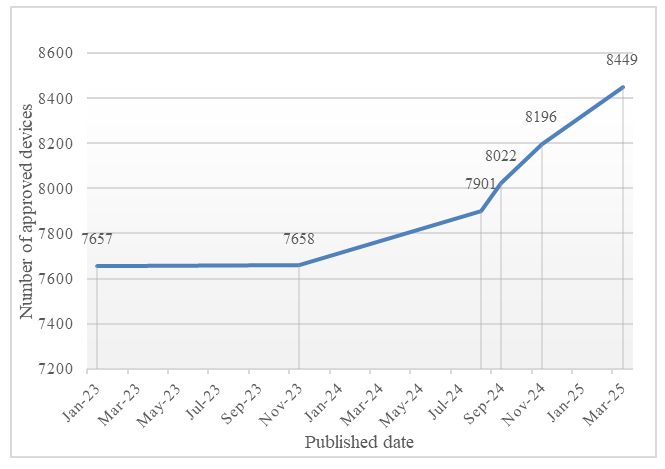

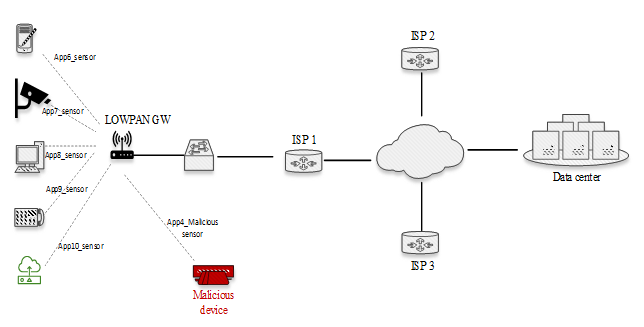

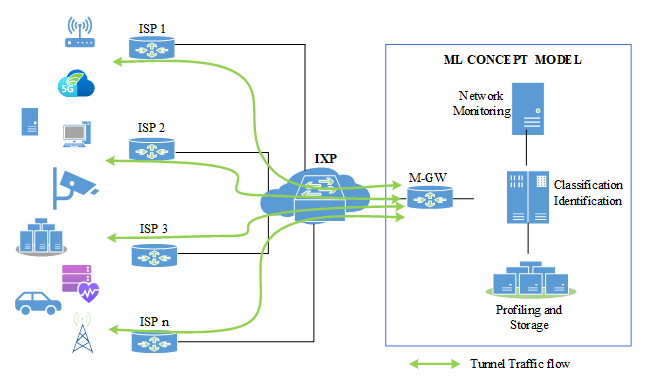

Traditional Network Access Control (NAC) systems predominantly depend on predefined rules, authentication protocols, and static policies to manage and regulate network access [14]. However, the escalating sophistication of cyber threats, particularly Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks and data breaches orchestrated through compromised IoT devices, has exposed the limitations of these conventional mechanisms. As a result, there is a growing need for intelligent and adaptive NAC solutions capable of responding dynamically to evolving network behaviours.Moreover, as highlighted by [15], most existing scholarly discussions on IoT security primarily focus on issues such as privacy, data protection, and general network security, while access control mechanisms remain relatively underexplored. This gap underscores the importance of developing context-aware NAC frameworks that can autonomously detect, classify, and regulate internet connected devices. The proposed ML model leverages MAC layer and physical layer payload data to identify and detect malicious IoT devices based on anomalous network behaviour. The study in [16] emphasizes that detecting IoT devices directly at the Internet Service Provider (ISP) level offers greater visibility into device behaviours and suspicious traffic patterns than relying solely on small-scale testbeds or home environments. In Zambia, this aligns closely with the structure of the national network ecosystem, where a limited number of ISPs provide the bulk of backbone connectivity. By leveraging detection at the ISP layer, Zambia can capitalize on existing centralized choke points in its network infrastructure to monitor device activity more effectively across subscriber lines. For a broader and more centralized coverage of IoT threat detection, deploying the proposed Machine Learning (ML)-based NAC model at the Internet Exchange Point (IXP) represents a more strategic and effective solution. The IXP serves as the primary aggregation hub for inter-ISP traffic, as illustrated on Figure 10 making it an ideal vantage point for monitoring, classifying, and mitigating malicious network device activity across multiple networks. Integrating detection mechanisms at both the ISP and IXP levels would therefore enhance Zambia’s national cybersecurity posture by enabling early detection, coordinated response, and regulatory oversight of IoT devices connecting through domestic and international gateways. | Figure 10. Integration at the IXP, which serves as the central interconnection hub for ISPs |

5. Conclusion and Future Work

This study demonstrates the feasibility of applying machine learning (ML) within Network Access Control (NAC) systems to enhance IoT security in Zambia’s digital ecosystem. Using NetSim, two network scenarios were simulated to analyse throughput, delay, and payload characteristics under normal and malicious traffic conditions. The Random Forest algorithm achieved an overall detection accuracy of 91%, successfully identifying devices exhibiting abnormal payload behaviours. The model effectively distinguished legitimate IoT devices from rogue nodes, offering a data-driven foundation for improving regulatory oversight and secure device certification.The research also proposes a dual-layer detection architecture that integrates ML-based NAC mechanisms at both ISP and IXP levels. This structure enables centralized visibility, early threat detection, and coordinated response, supporting Zambia’s Digital Transformation Strategy (2023–2027) and Vision 2030 objectives for a secure digital infrastructure.Future research will focus on collecting real network traffic data using tools such as Wireshark, PRTG, and NetFlow analysers to train and validate the ML model under real-world conditions. This will enhance the model’s adaptability to diverse IoT environments and traffic patterns. Further studies should explore advanced learning techniques such as deep learning and federated learning for adaptive device identification. Integrating the model with enterprise NAC systems (e.g., Cisco ISE, FortiNAC) will also allow automated isolation of rogue devices. Additionally, collaboration with Zambia Information and Communications Technology Authority (ZICTA) and Zambia Bureau of Standards (ZABS) is essential to align ML-based detection outputs with national internet connected devices type approval and certification frameworks, ensuring a secure and well-regulated digital environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Tembo for his supervision, insightful guidance, and constructive feedback throughout the course of this study. I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to my friends and colleagues for their continual encouragement and moral support throughout the course of my studies. I am grateful to my wife, whose unwavering motivation and steadfast support provided the strength and inspiration that sustained me through this academic journey.

References

| [1] | Fitzgerald, M., Kruschwitz, N., Bonnet, D., & Welch, M. (2014). Embracing digital technology: A new strategic imperative. MIT sloan management review, 55(2), 1. |

| [2] | Paul, Justin; Ueno, Akiko; Dennis, Charles et al. / Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary perspective and future research agenda. In: International Journal of Consumer Studies. 2024; Vol. 48, No. 2. |

| [3] | (04, March 2024) The Role Of IoT Solutions in Driving Digital Transformation, Marco Almeida, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://telecoms.adaptit.tech/blog/the-role-of-iot-solutions-in-driving-digital-transformation/. |

| [4] | (20 July 2024) Internet of Things (IoT) and non-IoT active device connections worldwide from 2010 to 2025, [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1101442/iot-number-of-connected-devices-worldwide/. |

| [5] | Republic of Zambia, Ministry of Technology and Science, “Inclusive Digital Economy Status Report” 2022. |

| [6] | Access Control In IoT Networks: Analysis And Open Challenges. ICICC2020: International Conference On Innovative Computing And Communication. Rajiv K. Mishraa, Rajesh K. Yadavb. |

| [7] | Ministry of Technology and Science, “National Digital Transformation Strategy”, 2022. |

| [8] | Marko Šarac, Nikola Pavlović, Nebojsa Bacanin, Fadi Al-Turjman, Saša Adamović, Increasing privacy and security by integrating a Blockchain Secure Interface into an IoT Device Security Gateway Architecture, Energy Reports, Volume 7, 2021. |

| [9] | Kalunga, Joseph & Tembo, Simon & Phiri, Jackson. (2020). Industrial Internet of Things Common Concepts, Prospects and Software Requirements. International Journal of Internet and Distributed Systems. 1-11. 10.5923/j.ijit.20200901.01. |

| [10] | Hafeez, I., Ding, A. Y., Antikainen, M., & Tarkoma, S. (2018, August). Real-time IoT device activity detection in edge networks. In International Conference on Network and System Security (pp. 221-236). Cham: Springer International Publishing. |

| [11] | Hamza, Ayyoob & Habibi Gharakheili, Hassan & Sivaraman, Vijay. (2020). IoT Network Security: Requirements, Threats, and Countermeasures. 10.48550/arXiv.2008.09339. |

| [12] | Liu, Yongxin & Wang, Jian & Li, Jianqiang & Niu, Shuteng & Song, Houbing. (2021). Machine Learning for the Detection and Identification of Internet of Things (IoT) Devices: A Survey. 10.48550/arXiv.2101.10181. |

| [13] | Fatima Alwahedi, Alyazia Aldhaheri, Mohamed Amine Ferrag, Ammar Battah, Norbert Tihanyi, Machine learning techniques for IoT security: Current research and future vision with generative AI and large language models, Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems, Volume 4, 2024, Pages 167-185, ISSN 2667-3452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iotcps.2023.12.003. |

| [14] | Cruz-Piris, L., Rivera, D., Marsa-Maestre, I., De La Hoz, E., & Velasco, J. R. (2018). Access control mechanism for IoT environments based on modelling communication procedures as resources. Sensors, 18(3), 917. |

| [15] | Ravidas, S., Lekidis, A., Paci, F., & Zannone, N. (2019). Access control in Internet-of-Things: A survey. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 144, 79-101. |

| [16] | Said Jawad Saidi, Anna Maria Mandalari, Roman Kolcun, Hamed Haddadi, Daniel J. Dubois, David Choffnes, Georgios Smaragdakis, and Anja Feldmann. 2020. A Haystack Full of Needles: Scalable Detection of IoT Devices in the Wild. In Proceedings of the ACM Internet Measurement Conference (IMC '20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1145/3419394.3423650. |

= 0.04 seconds In NetSim, packet transmission timing is represented in microseconds (µs) rather than in seconds or milliseconds. Consequently, to achieve the desired throughput configuration, the corresponding inter-packet arrival time value of 40,000 µs must be entered into the simulator settings as illustrated in Figure 2.This configuration ensured that each device contributed a predictable and uniform traffic flow, resulting in a combined offered load of 50 kbps across all five sensors. Scenario 1 provided a stable baseline environment that served as the benchmark for assessing the impact of additional or malicious traffic, enabling comparative analysis of subsequent performance deviations introduced by abnormal network activity.Scenario 2, with topology setup Figure 4, extended the baseline by retaining the same configuration for the five sensors while introducing an additional application, App4, transmitting with the same packet size (50 bytes) but at a substantially higher throughput of 400 kbps. The purpose of this configuration was to simulate a rogue or malicious IoT device generating excessive traffic, thereby producing network distress.

= 0.04 seconds In NetSim, packet transmission timing is represented in microseconds (µs) rather than in seconds or milliseconds. Consequently, to achieve the desired throughput configuration, the corresponding inter-packet arrival time value of 40,000 µs must be entered into the simulator settings as illustrated in Figure 2.This configuration ensured that each device contributed a predictable and uniform traffic flow, resulting in a combined offered load of 50 kbps across all five sensors. Scenario 1 provided a stable baseline environment that served as the benchmark for assessing the impact of additional or malicious traffic, enabling comparative analysis of subsequent performance deviations introduced by abnormal network activity.Scenario 2, with topology setup Figure 4, extended the baseline by retaining the same configuration for the five sensors while introducing an additional application, App4, transmitting with the same packet size (50 bytes) but at a substantially higher throughput of 400 kbps. The purpose of this configuration was to simulate a rogue or malicious IoT device generating excessive traffic, thereby producing network distress.

0.001second = 1000 µs. Figure 5 shows the malicious device App4 sensor configuration.

0.001second = 1000 µs. Figure 5 shows the malicious device App4 sensor configuration.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML