-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Computer Science and Engineering

p-ISSN: 2163-1484 e-ISSN: 2163-1492

2020; 10(1): 7-21

doi:10.5923/j.computer.20201001.02

Approach to Methodology and Design Issues for a Customised Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) Model/Framework for the Universities in Developing Countries

Aaron A. R. Nwabude1, Francisca Nonyelum Ogwueleka1, Martins E. Irhebhude2

1Department of Computer Science, Nigerian Defence Academy, Ribadu, Kaduna, Nigeria

2Department of Computer Science, Nigerian Defence Academy, Ribaudu, Kaduna, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Aaron A. R. Nwabude, Department of Computer Science, Nigerian Defence Academy, Ribadu, Kaduna, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The use of virtual learning environment for teaching and learning provision is one of the concepts that are changing the frontier of knowledge acquisition in today’s educational arena. The flexibility of online learning space can offer developing countries great opportunities in supporting varied learning methodologies. This study is about the development of customised VLE framework/model for use by higher institutions in the developing countries, particularly in Nigeria. However, in this paper, we examine only the methodological aspect of the entire research and context within which the current research study was situated. The paper starts by discussing the theoretical perspective underpinning the study and in that aspect provides constructivism as the adopted paradigm. The paper further examines epistemological principles and research design mechanism presented by [15] which includes four (4) principle elements that inform one another in the process of designing a study. These principles include; Epistemology, Theoretical perspective, Methodology and Methods: these are discussed within the methodological framework. This is followed by the identification of methods of data collection, research samples and professional ethics which are keys to the management of research study. This article further describes the fundamental concepts of validity, reliability and generalizability as applicable to this research and finally, presents the contribution of the research in the light of previous studies.

Keywords: Virtual Learning Environment (VLE), Customized Framework/Model, Developing Countries, Higher Institutions, Conceptual Framework, Methodology, Case Study

Cite this paper: Aaron A. R. Nwabude, Francisca Nonyelum Ogwueleka, Martins E. Irhebhude, Approach to Methodology and Design Issues for a Customised Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) Model/Framework for the Universities in Developing Countries, Computer Science and Engineering, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 7-21. doi: 10.5923/j.computer.20201001.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The past 30 years have seen computer science and technology education occupying a significant position across all educational sectors and economy with some technologies’ being used more than others in these sectors. Although, the use of these technologies, for example; the VLEs which are assumed to support constructivist approaches to teaching and learning wherefore knowledge is enhanced, implementation into practice have not radically changed didactics [1]; [2]. Literatures suggest that the use of technology in the classroom is the digital way of communicating knowledge; it is also about creating contexts for authentic learning [3]; [4]. Although, VLEs are being promoted and encouraged by various governments and stakeholders in education arena through policy formation, training and funding [5] the actual integration into practice appear to be limited to instructors and students ability, competence and enthusiasm to use and integrate across disciplines hence, some variability in usage levels and outcomes. As a result, research studies in the field suggest that any possible inconsistencies in the use of VLE, even where the technology is assumed to be available is a result of lecturers’ level of technical knowledge, belief and ability in which they act [6]; [7]; and [8].This study is concerned with the development of a customised software system model: the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) framework/model for teaching and learning provisions in the developing countries with particular reference to its use in Nigerian universities. The VLE software system can effectively be used as vocational and academic strategy for instructional competence [9] besides using it as management tool to synthesise functionality of computer-mediated ([10], environment. In this context, VLE is viewed mainly in relation to its adoption and integration into teaching and learning provisions with the aim of facilitating learning experience of the target users (TU) at institutional settings. Therefore this system is not to be seen on the basis of how technology (VLE) is designed in a particular way with the characteristics of core course content in mind. This paper discusses the study in relation to methodology adopted in the current research through systems document-led approach, analysis and nature of design. As noted by [11], methodology in itself is the theory of how inquiry should proceed. It explicates the choice made by researcher with regards to processes and methods used including forms of data gathering and techniques of analysis [12]. ‘Methodology’ according to [13] refers to the general principles which underline how researchers investigate the real world and how we demonstrate that the knowledge generated is authentic, credible and valid. In support of the above statement, one of the pioneer authors [14] argued that; all social sciences including computer or “educational researches are socially and politically entrenched. It is always undertaken by real person or persons, within a particular context, for a designated purpose. Therefore, research does not just happen, it is planned to greater or lesser degrees and has an overall design strategy for what it hopes to achieve, which is a claim to knowledge, how it is going to gather and present data in support of the claim to knowledge, and how it is going to show validity of the claim to knowledge through some kind of legitimization process”.Notably, following from the aforementioned statement, this paper aims to discuss the underlying principles governing the conduct of this research, and with degree of certainty justify any decisions and assumptions made in the process, so that such might be assessed in relation to the study. Therefore, in the process of designing research study, various terminologies such as epistemology, ontology, theoretical perspectives, conceptual framework etc., come into play, and many a time, researchers throw theses terms “together as if they are comparable terms” [15]. They are not, in fact all of the terms are rather decision making concepts and researchers need to find that which is suitable in their own research. It thus appears then that decisions for research designs and analysis are usually woven into narratives and should be applied in an orderly manner [15]. In the current study, the researcher aims at investigating how the use of software technology (VLE) by the university lecturers and students mediates or enhances pedagogic (strategies of instructional) competence at tertiary educational levels in the United Kingdom and Nigeria. It is hoped that by exploring the use of a VLE, and observing how instructors and students interact with the system in their teaching and learning practices, using detailed epistemological framework might establish whether or not a VLE is in fact a useful tool in mediating teaching and students’ learning experience at higher institutional levels.

1.1. Epistemological Structure

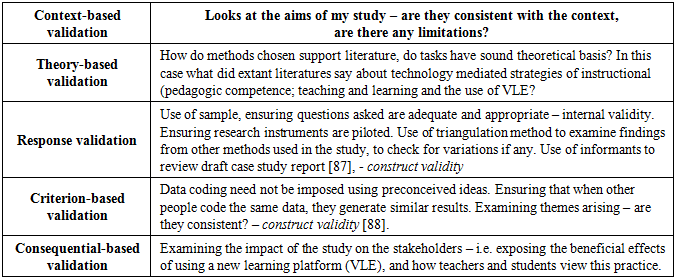

- Considerably, in designing the current study, the researcher is guided by Crotty’s epistemological framework. [15] suggests that the foremost part of exploratory study is in the design mechanism; that is, designing the research question and getting the questions right. He ultimately describes in orderly fashion four design elements that inform one another in the process as displayed in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Overview of Crotty’s Epistemology Framework, [15] |

1.2. Theoretical and Philosophical Considerations

- It seems obvious that when we are faced with a demanding approach to subjective or objective analytical conceptions such as ideas and beliefs about our studies or project activities, we are faced with problems. We then begin to wonder in our own perceptive thinking, how we go about the problem, how we explore sufficient details based on our beliefs and experiences, what method(s) we are going to use, and how we can justify that the methods used are appropriate to our study project. Extant literatures in research appear to suggest that there is no single way of conducting a study [23]; [24]. This means that the process of selecting research strategy to design requires the involvement of key issues of philosophical assumptions as well as distinct methods [25]. Therefore, research type chosen by a researcher will depend on its appropriateness for; (a) particular kinds of investigation and (b) for addressing particular kinds of theoretical and practical problems, but also will depend on the nature of question that are being investigated. In his later thought, Denscombe describes good research in terms of 'fitness for purpose' and then outlines various types of strategic approaches to research [23].How important it is, to reflect on the issues of philosophical underpinning of this research? Analysis reveal that often times, we are reminded that our views of research depend mainly on our views about how knowledge is gained and how it is communicated [26]. Opie argues that if we view knowledge as ‘hard, real, and capable of being transmitted in tangible form; then we have an empiricist’s view of knowledge, and as a result we are most likely to use quantitative research approach to associated method of data collection [23]. Conversely, if we view knowledge as ‘soft, subjective, and based on our experience and insight of an essentially personal nature’ then we have rationalist’s view of knowledge, and as a result we are most likely to use qualitative research methodology. Historically, in computer science as part of natural sciences and social science field, researchers have often taken to quantitative but recently a blend of the quantitative and (or) qualitative research strategies [27]; [28]; [29]. Literature observes that quantitative research approach often tests a theory that is composed of variables in order to generate statistical or numerical data through the use of large-scale survey research. Qualitative research approach on the other hand involves building a complex picture and detailed views of informants [25] by asking questions about why and how people behave in the way that they do. It is not surprising therefore, that these two research strategies oppose each other in a way that flames tension and debate within the community of researchers.Providentially, literatures are replete with records of tension between the quantitative research approach with its attendant positivist assumptions and the qualitative research approach with its own interpretivist methodologies [30]; [31]; [32] It is therefore, the apparent contradictions and tensions that produced two opposing paradigms (worldviews) such as positivism and constructivism. Both worldviews have their roots in the quantitative and qualitative research traditions [33]; [34]. For instance, a positivist researcher is often associated with quantitative, while a constructivist or interpretivist researcher is associated with the qualitative research. Interestingly, within the critics of positivism and constructivism, a third paradigm known as pragmatism or mix methods emerges. In their opinion, for instance, [28]; [35] argue that the pragmatist or mix methods researcher draws understanding from the strengths of both the quantitative and qualitative approaches. Although, in accordance with literature, [36], a mix-methods paradigm and their associated methods appear to have received more attention in recent years. As a matter of fact, researchers in the field of computer science usually align themselves with broad range of approaches [37], giving room for the use of mix methods strategies. It is therefore imperative that a researcher fully understands the prevailing worldviews with its underlying philosophical assumptions [38] in the conduct of research study. In the section below is the researcher’s philosophical research position which emphasises underpinning assumptions and reasons for its strategy in the current study.

2. Research Position

- In consideration of philosophical positioning for this study, the researcher examines theoretical underpinnings adopted by other researchers in the computer - technology field. Some of them have taken to positivism, while others have considered interpretivism /constructionism. The researcher then considers own position based on assumption and associated worldview that closely matches the current study. For these reasons, the position within the realms of constructionism /interpretivism research paradigm appears most suitable. The current research therefore, adopts constructivism position and this is guided by characteristics underlying the quantitative and qualitative research design.In adopting constructivist/ interpretivist paradigm [39], the researcher believes that meanings are embodied in the language and actions of the social actors [11]. In other words, the researcher believes that the social world can only be understood by occupying the frame of reference of the participants in action. So what epistemological dimension has the researcher taken to find answers to the question? Epistemologically, the researcher in the present study is trying to find answers to the question on the “technology mediated strategies of instructional (pedagogic) competence” by presenting four case studies of 120 college students, and 4 instructors in a tertiary institution in East London, England, and another 120 university students and 12 instructors from three tertiary institutions in Nigeria comprising; the NDA Kaduna, ABU Zaria and Covenant University, Otta. Finally, in his personal view, researcher as a constructionist in the current study believes that there is no valid interpretive meaning of reality; rather meaning is constructed as a form of new directions of social realities, and in this instance, it is for the process of interpreting the use of VLE in teaching and learning delivery, providing enhanced learning experience and developing framework for a customised VLE in Nigeria. It is explicable therefore, to say that the choice for social constructionism follows the fact that various researchers in the computing, engineering, education and allied fields who have championed the use of technology (VLE) in computing, technology and educational reforms have advocated the use of social constructivism as a panacea for effective learning process [40]; [41]; [42]; [43], Thus, social constructivism in the context of this study emphasises knowledge built upon existing knowledge, experience, reflections, and it involves the development of higher cognitive skills by the student as the student begins to construct knowledge in his or her own style [44]; [45]. Parenthetically, within the framework of social constructivism/interpretivism, epistemology and ontology appear to share the same platform. This means that when you talk about the construction of meaning (epistemology), you are at the same time talking about construction of meaningful reality (ontological) [15]. Ontologically therefore, the researcher shares the views that social reality is a product of a process by which social actors negotiate meanings for actions and situations which is a complex of socially constructed meanings [46]. The researcher also believes that social realities are not just out there (indicated above) to be discovered by other researchers, but can be constructed by individuals as they make sense of their surroundings [47]; this way knowledge is produced. In summary therefore, the application of the interpretivist epistemology and the subjectivist ontology in this study might enable the researcher to understand more about the assumed lack of technological and pedagogical competence (if any) by users of a VLE in the research contexts. The results of the research in turn might provide further evidence which translates to the students developing higher cognitive skills, learner-centred, and active learning [44]; [48]; [49]. Furthermore, by taking social constructivist background, and interpretivist theoretical perspective (knowledge as a product of individual’s culture and surroundings) captures the aim and objectives of this research and ensures that through appropriate use of customisable pedagogical VLE platform, effective teaching and learning in all educational sectors and allied industries might be enhanced. In the section following, it becomes sufficiently paramount perhaps, that research narrative follows constructivist approach and overviews the conceptual framework/models within computer science and software technology management in e-learning as appropriate in this paper.

2.1. Research Description and Conceptual Framework

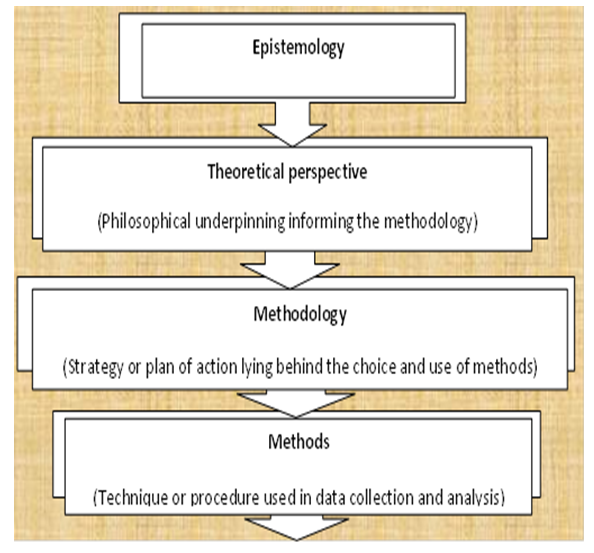

- For the empirical model, this research observes a close correspondence between two phenomena, the dependent and independent variables. This study used mathematical model to analyse collected research data abstractions of the real world which represents an approximation of the real system. Furthermore, the interpretivist approach chosen in this study enabled the study of phenomenon through a case study design approach which utilises data based on evidence from the real world and real people in their natural settings at the present time [50]; [51]. This approach seems most appropriate for this study at the present time because it enables thorough examination of the constructs through a prism of strategies in four higher institutional environments. The institutions were selected based on Expert panel recommendations and willingness to participate within the stipulated research timeframe. The study initially selected 6 cases however; two were later dropped because they were unable to meet the timeframe.A conceptual framework for planning this research is shown in Figure 2.

| Figure 2. Conceptual Framework |

3. Material and Methods

- This paper discusses the study in relation to methodology and methods adopted in the current research setting through systems document-led approach, analysis and nature of design. As noted by [52], methodology in itself is the theory of how inquiry should proceed. It explicates the choice made by researcher with regards to processes and methods used including forms of data gathering and techniques of analysis [53]. However, when we look at methodology as a whole, we refer to a constructive framework, a systematic process which provides research design, methods, approaches and strategies used in an investigative study [54]. For example, selection of participants, instruments used, data gathering and data analysis used in this study are all parts of academic practices used in an investigation in order to answer research question [55].

3.1. Research Design: Case Study as Research Approach

- In this paper therefore, we present a case study research method that was conducted in order to understand the lecturers and students’ experiences on the uses of VLE in two distinct international environments: the United Kingdom and Nigeria contextually. Whereas, the survey provides a wide-ranging representation of the tertiary institution’s lecturers and students’ experiences on the uses of virtual learning environment, case study research method adopted in this study becomes necessary because it provides in a nutshell detailed investigation of these experiences and how the experiences are shaped in the study. This has therefore, provided opportunity for sequential collection of data which in turn made available indications and features to address subsequent data collection and analysis. The use of inductive process (generating theory for testing) rather than deductive (testing theory) in this study enabled the study to move from specificity to general observation of data. The current study undertakes a small scale interpretivist case study perspective and its adoption is firstly, to enable an in-depth exploration of the use of a VLE, including problems militating against effective use by the undergraduate students and university lecturers in their teaching and learning experiences at two different research contexts [56]. Secondly, since the nature of this study is to explore, interpret and put together a framework for the use of a VLE in Nigeria, case study strategy enables the researcher to sequentially examine specific case(s), collect data, analyse the data and interpret results within the context before moving to the next [57]; [58]. Therefore, based on this intent, the study employs intrinsic case study as described by Grandy: An intrinsic case study is the study of a case (e.g., person, specific group, occupation, department, organization) where the case itself is of primary interest in the exploration. The exploration is driven by a desire to know more about the uniqueness ... [59]The key word here is the researcher’s interest. In a very remarkable way, computer and technology are bringing learning to life and the fact that one can be able to communicate with the instructors and life lessons from anywhere and anytime. Thus, my special interest in employing intrinsic case study in this subject in order to further enable a better understanding of the uniqueness of the phenomenon [60]. Moreover, the existing methodology and design approach chosen in this study, as any other human endeavour enables adequate exploration of the phenomenon, yet punctured with some limitations. These and others are discussed in the sections following, starting with reason for choice of case study.

3.2. Reason for Choice of Case Study

- In this study, a central goal was to understand the social phenomena inherent with the use of a VLE in approaching teaching and learning by the undergraduate learners’ and their teaching instructors in different tertiary institutional and environmental settings. Because of its’ inherent qualities, it is massively expected that with the inclusion and use of case study as a method approach might produce a unique explanation and interpretation of individual educational experiences in learning with the VLE’ [61]. This might give way to designing a customisable VLE framework for use in Nigeria. Generally speaking, the choice of research strategy to a greater extent depends on factors such as the nature of research and research questions that the researcher wishes to address, the extent of control an investigator has over actual behavioural events, and the focus on contemporary technological issues as opposed to histories [62]. Bearing in mind, Yin’s statements that the ‘How’ and ‘Why’ questions are naturally explanatory, interpretative, and are best suited for strategies like case studies, experiments, or histories; my study consequently sets out to explore and interpret the use of a VLE in educational contexts by the university teachers and the students with anticipated outcome of improving provisions for teaching pedagogy within similar institutions. Evidence based research is an ever growing entity; case study approach has traditionally enabled researchers to contribute evidence –based research in their study areas according to [63]. In the current study, a case study located within the interpretivist tradition affords the opportunity to provide expected rich understanding of the life context and evidence-based research on real people in their natural settings [62]. Finally, for the reasons mentioned, taking the case study approach enables researcher to narrow down research sample size to manageable number of respondents in order to effectively plot the group’s reactions, and analyse the use of a VLE by the participants. The above reasons, coupled with research question, appropriately reinforce the decision to use case study as the methodological approach in this study.

3.3. Research Instrument and Data Collection Methods

- The choice of data collection methods used in a research study is usually influenced by the type of data collection strategy adopted, and most often times; researchers are presented with a variety of methods to choose from. There is however, no standardised prescription on what methods to use, nevertheless, a researcher needs to ensure that method(s) chosen are in line with the chosen methodology and it is likely to be reliable. As indicated earlier, the central question for this research is to investigate and analyse technology mediated strategies of instructional (pedagogic) competence: teaching and learning at tertiary institutions with particular reference to the current use of a VLE platform which might enable the development of a framework and a model to be used in educational delivery in Nigeria. Having reflected on the researcher’s constructivist viewpoint and the drive to achieve subjective reality [64], the study opted for data collection and analysis that includes the following techniques;• Data collection method 1 - Questionnaire • Data collection method 2 - Interviews • Data collection method 3 – Class Observation The process of data collection and analysis followed a sequential approach, meaning that one phase of activity is completed before the next. This ensured that results of analyzed data in one stage became a precursor for, or provided evidence or themes for use in the next stage. Data were collected during the months of September 2014 running through to January 2015 in the first phase, and Oct 2017 up to February 2018 in the second phase.The analysis of data for this study was carried out in sequence, meaning that survey data was completed first; this is then followed by interview and finally the observation data. The survey data once completed was coded and then inputted into SPSS for descriptive analysis while, the interview and observation data were coded but analysed thematically. The descriptive analysis of survey data generates frequency tables, charts and percentages while the thematic analysis provides themes for identification of features or categories of any reported uses of VLE or problems inherent in its use.

3.3.1. Data Collection 1 – Student Questionnaire

- Data collection in this research study generally involves designing, developing and validating survey instrument: the students’ VLE usage Survey (SVLEU-Survey). This is an instrument designed by the researcher to explore baseline data about the use of VLE in teaching and learning at case study institutions in London, UK; Kaduna, Zaria and Ota in Nigeria. The design of questionnaire instrument which contained research questions were intended to identify participant’s thinking as they provide answers on their experiences about access and uses of a VLE for processing learning. Therefore, in order to assess the respondents’ perceptions and then address the research questions on the uses of a VLE; the following six items generated from literatures and research question becomes the guiding constructs and are included during the design and development of the instrument. They include; I. About you - the general and personal background functions. II. About you & your studies – subject of study and type of VLE in the College. III. About the VLE generally – level of interactivity. IV. About the activities – using VLE mediating tools generally V. About your homework in and out of the classroom learning environments VI. About the VLE support generally; learners’ acquisition of skills and digital literacy. To administer the questionnaire, it was important to remind us about the piloting of research data. The questionnaire instrument was piloted upon receipt of research approval from the University of East London (UEL) ethical committee where the study originated. For this practice, a draft version of the survey instrument was produced. This version of the questionnaire was then piloted in a similar tertiary institution in East London, other than the case study institution. It was distributed face-to-face, to15 participants however, only 10 copies were collected back after a period of 3-days, giving a return rate of 67%. The reason for the pilot survey was not to test participant’s attitude scale but to test the validity/viability and appropriateness of the questionnaire items and processes on the target group. The same intentions and processes were also extended to the interview and observation instruments respectively. There were three institutions selected for pilot however, only one accepted to take part within the allocated timeframe. At the end of the pilot, it became necessary to make some changes both in the structure and contents to reflect the groups under the investigation. Nonetheless, the responses from the pilot in relation to the questions indicate that the questionnaire was a true and valid instrument for data collection in this study. For this reason, the questionnaire instrument was subjected to further scrutiny by the research team, giving way for the adoption of revised version. The revised and final version of the questionnaire instrument that contained a list of research questions as described above was addressed to the university students at various research institutions under the study. This version was used in the main study as a valid and authentic version for collecting data that are quantitative during the months of September 2014 running up to January 2015. This instrument was distributed to the participants’ through face- to- face personal contact after due explanation and instruction on how to fill it in. It must be borne in mind that the use of questionnaire in this study was to collect complementary data; this means that participants were required to choose answers from fix options. The process of distribution and collection of questionnaire took four months because the process was conducted class by class and that took unnecessarily more time period than expected to complete. Secondly, and more important is the fact that university environments are always busy with various inductions, academic exercises and other activities, and because of that the gatekeeper advised to allow ample time for participants to complete and return the questionnaires without unnecessary pressure. Finally, the questionnaires were collected and analysed. In the case of institutions in Nigeria, a little modification was made with the advice from my supervisors due to the student number and the current level of VLE usage in the case study institutions however; the process of data collection was practically the same. As indicated earlier, the analysis was conducted sequentially so, as soon as the survey was completed in each case/institution, the raw data from the questionnaire was manually coded and inputted into the SPSS for analysis. The univariate analysis was carried out on the data collected and the result captured a range of descriptive information while generating frequency tables and charts about any features of respondents’ uses of a VLE in their teaching and learning experiences.

3.3.2. Data Collection 2 – Semi Structured Interviews

- After the analysis of questionnaire was completed, the semi –structured interview was then designed and used to collect data that are more in-debt and rich qualitatively within the available time limit. It is often a general idea that qualitative research follows an inductive research process (Instructional Assessment Resource [65] of reasoning, and involving the collection and analysis of non-numerical data using interviews, observation or document analysis instruments in order to search for patterns, themes and holistic features. The interview process used in this study enabled further understanding of how best university teachers and learners use a VLE. Similarly, just as with the questionnaire, this process involved researcher designing, developing and validating interview instrument which was also based on the six point items derived from literature as with the questionnaires instrument above. This was designed and developed for the tertiary institutions’ academic teachers.To obtain maximum and valid outcome on the lecturers’ competence, interview rather than questionnaire should serve the purpose better, hence the interview to teachers. Besides, since the study involves observation of both the instructors and their students in a practically classroom situation, the researcher in consultation with the supervisory team felt that these three instruments (interview included) might significantly generate reasonably realistic data for analysis. Thus, the reason why the questionnaire was not administered to the teaching staff? In line with questionnaire; administering semi-structured interview followed the same pattern where interview instrument was piloted at a similar college environment in East of London on the 15th October 2015. In this exercise, the researcher visited three (3) colleges and one University institution with a letter requesting access to pilot the study. Only one of the institutions visited responded positively, and this was chosen. The pilot interview was directed to a member of the teaching staff at the chosen institution other than the case study institution. It addressed all the questions and provided context to further explore subsequent interviews and the third research instrument (Observation). The format for the interviews followed semi-structured design principle while providing prompts for further questions. The piloted semi-structured interview process enabled researcher to collect data on the teacher’s strategies of instructional (pedagogical) and technological competence in the use of a VLE for teaching and learning provisions. The interview data was transcribed and analysed using content analysis and result facilitated in reshaping the final interview instrument which was later used in the study. The pilot exercise again suggests that the questions were suitable for the 45-60 minutes interval allocated for it however, changes were made to the structures and some of the questions also changed positions or discarded altogether. The adopted second version of the interview instrument was later used. It is necessary to indicate however, that the structure and purpose of this interview were already defined in advance by the researcher. The defined characteristics were based on everyday teaching situations of those university teachers who use one form of a VLE or another in their teaching practice. As indicated, the interview was designed in a semi structured format, and there were rooms for prompts and personal opinions, again with little modification in the case of the Nigerian situations. It was accordingly directed to sixteen (34) teaching staff altogether in the four tertiary institutions, and the duration lasted for between 45 – 60 minutes maximum depending on the responses and time allocation by the teaching staff involved. All the interviews were recorded on tape and fully transcribed for detailed analysis. The interview process took place in a small quiet office provided by the gatekeeper in one of the institutions, and others in the classroom. The line of questions centres on the general VLE access and usage, and the instructors’ technological and pedagogical competence in providing teaching and learning. They also touch on issues such as; interactivity between teacher and students in and out of classroom environment, information on teachers’ perceptions of their technological and pedagogical competence, and the variability (if any) in strategies linking students’ learning outcomes. Data collected in the process were later transcribed and analysed to generate decision making models/tools. Semi-structured interview process provides the opportunity of collecting rich data naturally from the respondents. It also enabled the researcher to ask already prepared sample questions which guided the research, and clarifications of initiated follow-up questions where needed from the respondents.

3.3.3. Data Collection 3 - Observation Technique

- [66], have described classroom observation as re-emergence of method, under renewed interest for evaluating instructional practices in a research study. In order to gain more insight into the innovative VLE usage and ensuring that optimal responses are obtained in this study, researcher employs observation technique as the third source of data gathering. Observation technique according to literatures enables researchers to participate in learning events in order to better understand the insider’s experience [67]; [68]. The relative value of data collection in this form is to contextualize the interview data collection and complement the use of questionnaires from the students’ perspective. This is done to further enhance reliability and consolidate findings. In designing a non-participant observation variant, the researcher takes cognisance of the fact that many a time virtual learning environment as educational technology (edtech) platform has been measured through self-reporting surveys of the use and results. With the above in mind, we objectively developed one observation instrument which sought for answers on the strategies of instructional (pedagogical) uses of a VLE in providing teaching and learning within the four subject disciplines described in the later sections which include: Mathematics, Chemistry, Computing, and English language and others at the concerned case study institutions. The following constructs which were based on research questions and reviewed literature, and then carried out within the framework were observed; I. Teachers and students VLE usage, II. VLE tools integration by the students and teachers, III. The role of student and VLE engagement, IV. The role of teacher and the pedagogy of teaching and learning, V. Class organisation (whole-class working or individually) during the observed sessions. The operationalization of the observation items enables the researcher to obtain information that reflects the experiences of both students and teachers in their current teaching and learning practices within the classroom context. It is of particular importance to note that prior to this observation being carried out, and in accordance with the sequential approach to data collection and analysis adopted, students and teacher’s questionnaire and interview data respectively have been collected and analysed. However, in the case of Nigeria, observation did not take place for the same reason: usage level which at the moment is very low. Administering non-participant observation instrument follows in likewise manner the same principle as others in the study on the 22 April 2016 at a similar tertiary institution outside the borough of case study institution. As expected, there were changes made to the observation instrument which reflects the current instrument status used in the process. However, the final reconfigured non-participant observation instrument was adapted from UCIR Classroom Observation Protocol and this was used as the main observation instrument. It is my belief that the non-participant observation variant used offers more “nuanced and dynamic” appreciation of the situations in a triangulated support of other methods in the study [69]. In terms of personal role as a researcher and observer in the study: researcher’s role assumes observer-as-participant. In this role, researcher is not part of the scene; however, participates primarily as an observer but with possibility of casually interacting with the participants to clarify some aspects observed in order to avoid any form of misunderstandings [68]. This observation was conducted so to corroborate what teachers and students said and did, in addition to how they use virtual learning environment (Moodle) practically in enhancing teaching and learning experiences of the users in the classroom setting. Therefore, with indirect non- participant’s observation variant, researcher attends classes four consecutive times, carrying out observations exercise across 4– chosen subjects under the study, and taking notes while lessons were in progress. A total of four observations were carried out on the teachers and students’ VLE interactivity in the classroom following themes that emerge as a result of completed questionnaires and interviews. Why four sessions? According to literatures, [70]; [71]; and [72], saturation refers to reaching a point at which gathering “fresh data no longer sparks new theoretical insight” or using the SAME methods is no longer revealing anything new or finding different results. Saturation of data is influenced in this study by the size of the sample, location, and the quality of data collection techniques used. Although, in this study, we are looking to explore a process in two different environments, data saturation was achieved after four observation sessions.

4. Validation Process

- The conceptual framework presented above (Figure 1) for planning this research was validated by the use of empirical data collected from fieldwork. The key elements of the framework which were derived from literatures were validated from the results of case studies. The case studies which comprised of 4 higher institutions in two different international locations were visited to conduct survey, interviews [73], and observations. Communicative validation exercise developed by [74] was used in interviews with staff and students, who were involved in this process, thus the experiences which led to documentation of good practices. This ensures validity of conceptual framework.

4.1. The Professional Ethical Considerations

- Ethical issue is the ‘necessity to provide guidelines in a given research study’ [75]. It is therefore, ‘the justifications of human actions especially as those actions affect others’ within the study area [76]. Although, the truth axiomatically, is that this study might not pose any serious risk to the participating individuals; however, it is important to contemplate on issues of ethics and how that might impact on the participants and the study sites. In most fields of study, ethical issues might arise as a result of methods used by researchers. For instance; the nature of questions, the procedures adopted, nature of organisation, or even the types of participants in the study might signal ethical consideration [77]. In line with many other research investigations, ethical considerations become a serious matter especially when conducting research with young learners’ 16 to18 + years of age, which provides the legitimacy of involving young people in carrying out research without written permissions from their parents. From extant literature, we identified the following ethical issues: I. That a researcher should be aware of the commonly accepted ethical research principles which includes matters of informed consent, privacy, anonymity, confidentiality, betrayal and deception [78].II. That the researcher has to guarantee this confidentiality and anonymity of data prior to obtaining relevant data. III. That those respondents should be made aware of how much the researcher values being able to find out their opinions in the study [79]; [11]. Having the above in the back of our minds for this study, the involvement of young university adults in different educational settings requires that ethical issues be clarified before the commencement of data collections. For this reason, ethical guidelines for educational research produced by BERA become as important as the study itself [80]; [81]. BERA’s concept appears to be in agreement with [79], who argues that no researcher should gain access into any organisation without first obtaining permission from that organisation. As a result, we ensured that full ethical consideration with due respect for persons who are subjects of enquiry was adhered to and maintained by; I. Complying with the University of East London ethics committee regulations and thereby, completing ethics application form and received approval. II. Seeking approval from the Heads of the Faculty where data will be collected, as well as by teacher-participants themselves [82]. III. Approaching all participants formally through letters, inviting their voluntary participation in the study. These letters informed the participants that their participation was voluntary, and that they might freely withdraw from the study at any point without any penalty [26]. IV. Furthermore, through the letters, researcher pledged to protect the boundaries surrounding the shared secrets in the conduct of this study and assuring complete confidentiality of data and information. V. Assuring participants that collected data in the process, including digital and hard copies of recorded tapes, transcripts of students’ questionnaires and teacher interviews, and any notes will be saved in a locked cabinet in the University office for at least three years, after which they will be destroyed. VI. Participants were provided with documents describing the objectives of the study. Following, permission was therefore granted for this research to be conducted, and for researcher to use the participants’ data for the purpose of research (both in the pilot and the main study).

4.2. Ensuring Validity and Reliability of the Instruments

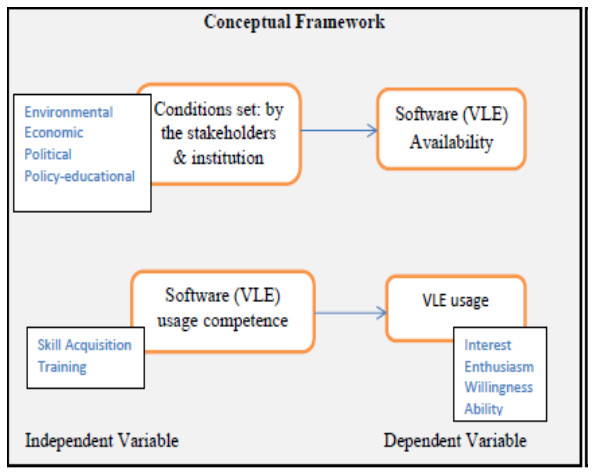

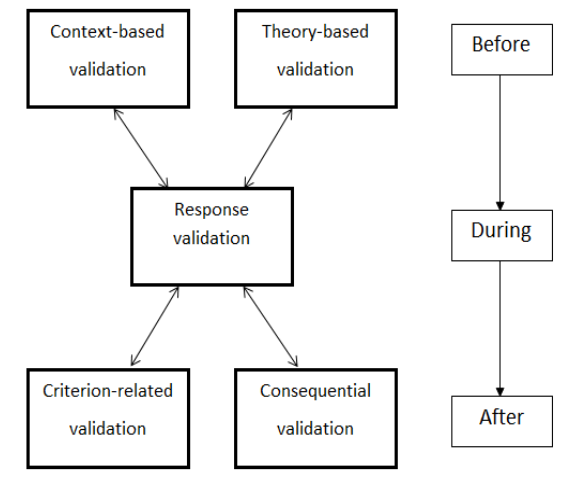

- Earlier in the introduction section, the concept of validation and reliability was mentioned in relation to methodology and general research design processes within the computer information and learning technology research as a framework for teaching orientations of the university lecturers. This framework links teaching conception with interactive practice which is based on indirect observation, and for this framework, validity is conceptualized as iterative – interactive - process of integrating instructional strategies that might produce scientific quality assurance in the study [83]. In considering the validity of this research, we examined validation framework offered by [84]; [85] which has a five-part three-stage structure developed earlier by [86] and adapted upon by [74]. These include: Context validation, Theory based validation, Response validation, Criterion related validation and Consequential validation. Figure 3, illustrates the internal arrangement of each stage and interrelated influences amongst the phases.

| Figure 3. Validation framework, [74] |

|

5. Research Population and Sample

- According to literatures, [90]; [91; and [92], sample in a study is simply a group of participants, or objects ‘taken from the population for measurement’ which essentially represents the whole population in an empirical study. The population in this study includes lecturers and students from 4 higher institutions who participated in the study by filling out survey questions and taking parts in interview and observation exercises across the case study settings. Specifically, the science students from one institution in the UK and the faculty of sciences and Art students from three institutions in Nigeria, including their tutors were chosen as representative mix of participants’ in their subject areas ranging from Computer science, Mathematics, Chemistry and English literature, Engineering, Medicine, Military science and inter-disciplinary studies and Art. The population is comprised of 120 student participants and 4 subject teachers from the UK institution, and 120 undergraduate students and 30 teachers from Nigeria institutions. This brings the total number of participants in this study to 240 students and 34 teaching staff. These participants took part in the study. Theoretically, the issue concerning population sample and research contexts understandably puts this research on a pedestal of non-generalizable empirical study. However, in this selection, consideration is also made of the purpose, the time scale and the constraints of the research, bearing in mind that this research is a small scale interpretive case study. It is therefore, the ultimate intention of the researcher to locate group of individuals that might provide rich insights into the phenomenon in the current study sites.

5.1. Questionnaire Sampling

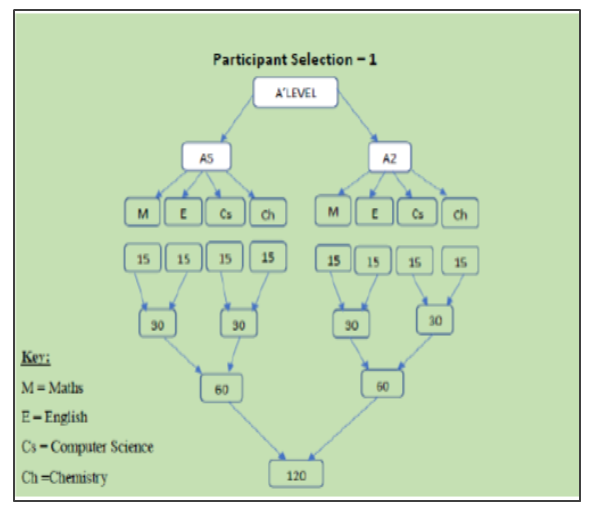

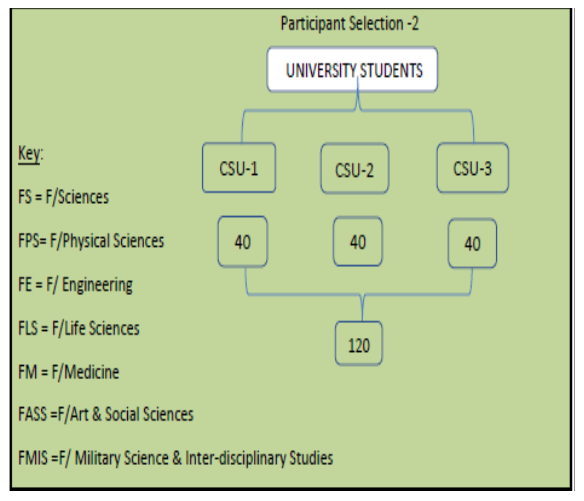

- The study adopts a purposive (non-probability) sampling strategy which enabled researcher to draw participants from predefined groups of students; the college learners in the 16-18 age group and the university students in 19 + age groups. These groups of participants (for example, the UK participants) were further divided into four in accordance with the four subjects’ cohorts chosen in the study for the UK research setting. The practicality of this process enables researcher to further group respondents by their study levels so to ensure that full opinions of the target respondents are fully represented in the study. This does not in any way mean generalisation. In terms of the actual number of participants and how they are comprised in the study, the sample include fifteen students selected from each of the four subjects, totaling sixty in each programme sector thus, making a total of one hundred and twenty (120) participants plus four tutors from UK institution, and another forty (40) student participants plus (10) tutors from each of the (3) universities in Nigeria, making a total of (120) student participants, and (30) tutors. However, in as much as we did not want to overweight any group, we did not forget the fact that a student who is studying for more than one subject/course within the four selected subjects or any other group under the study for that matter might in fact take part in filling out the questionnaire in more than one class. Nevertheless, we also believe that while this is likely to occur, it might not in any way jeopardise the validity of the sample and have no negative impact on the collected data, since respondents would answer the questions based on their experience in the subject areas. Following are the diagrammatic representations of our primary samples: sample 1 & 2 (Figures 4 & 5).

| Figure 4. Showing how participants are selected in the survey -1 |

| Figure 5. Showing how participants are selected in the survey -2 |

5.2. Interview Sampling

- In terms of the interview, purposive (non- probability) sampling technique is also adopted but based on pre-defined four subject cohorts in the study. The process is based firstly, on the selected subjects, secondly, on the teachers’ familiarity, attitude, interest, understanding and the rate of recurrence of the use of the platform in their practice. These attributes enable the study to select one subject teacher from each of the core subject levels thereby, making a total of four teaching staff from the selected (4) subject sectors in the UK tertiary institution. Again, there were no interviews with the Nigerian teaching staff, because of aforementioned reason (very low VLE usage level), coupled with dedicated timing for the completion of the study. Altogether, there were (34) teacher participants in the study, only (4) were interview. In terms of the observation sample, these 4 subject teachers in the UK and their students were observed in class.

5.2.1. Rationale for Choice of Sampling

- The rationale behind the choice of sampling is underpinned quantitatively by arguments put forward by other known researchers in the field; (e.g. [93]; [94]; [25]; [50] who maintain that in any quantitative survey research; sample size should not be fewer than 100 cases in a group and between 20 and 25 in each sub-group. This study ensures that selected sample size is within the predefined boundary. So, judging from literature and based on the case study approach that the study adopts, a non-probability (purposive) sampling method was more beneficial. The study also draws from literature researcher’s belief that a total sample size of (240) respondents [95] might generate important quantitative data for this study. Nevertheless, while this number might represent a diverse group of students in a case study institutions, this group might not be taken to be the representative group of the same class of students across England and Nigeria. For the qualitative rationalisation, researcher also observes the arguments presented in favour and against sampling techniques by different writers, (e.g. [96]; [97], [98]). For example, [98] observed that in a qualitative study, collected data might be used in the form of descriptive narrative as in a case study research or it might be exploratory in which case data might later be tested for correlation in a quantitative study. For Merriam purposeful sampling will enable the investigator to discover, understand, and gain insight of the phenomena from which the most can be learned” [96]. Following, and most importantly, in keeping to agreed timeline, purposive sampling appears a very useful technique for now in this study.

6. Novelty of Proposed Methodology Framework

- This paper presents methods approach that consists of theoretical and methodological framework for particular research work as part of its contribution to the body of knowledge in the field of computing and technology. From the [15]’s perspective, research design work needs to be fragmented and carried out within four stage elements that inform one another in the process. The originality of proposed framework is the development of amalgamated and customised VLE usability framework (CVLEF) that embodies constructs enabling students and teachers access to VLE platform usage the institutions. The idea is to use this platform within the university portal and also as a separate VLE App. Separate model: Customised VLE System Model (CVLESM) has been developed to address the benefits and problems of VLE usage in the affected regions. This facet confers the study a more holistic approach on the implementations and implications of the use of VLE in e-Learning practice in Nigeria.

7. Conclusions

- The paper clearly identified research methodology applicable in the study, which aimed at developing a customised VLE framework (CVLEF) with its attendant model (CVLESM) for use in the developing countries – particularly Nigeria. In line with the philosophical worldviews (paradigms) that shapes all kinds of research, this paper examined various studies in the field that have investigated the use of VLEs in teaching and learning (for example [99]; [100]; [101]; [102]) in order to select appropriate research design. Therefore, the research design technique that is holist, in line with prior studies within the thematic area, and capable of responding to the initial research question is chosen. Following, the paper discusses the theoretical perspective that is underlying the design which draws on several sources but guided by the principles of mix methods design approach [103]. Thus the adoption of the following constructs: constructivism as the theoretical underpinning, case study as the methodology frame, and mix method research approach which combines quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection. Consequently, the researcher is further guided by [15] design strategy and epistemological framework which ultimately describes in orderly fashion four design elements: (Epistemology, Theoretical perspective, Methodology and Methods). These principle elements inform one another in the study thus, enabling decision –making process within the study design.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML