-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Computer Science and Engineering

p-ISSN: 2163-1484 e-ISSN: 2163-1492

2013; 3(1): 1-7

doi:10.5923/j.computer.20130301.01

Wireless Routing in Ad-Hoc Networks

Tzvetalin S. Vassilev, Brian Eades

Department of Computer Science and Mathematics, Nipissing University, North Bay, Ontario, P1B 8L7, Canada

Correspondence to: Tzvetalin S. Vassilev, Department of Computer Science and Mathematics, Nipissing University, North Bay, Ontario, P1B 8L7, Canada.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Wireless networks present many challenges to standard routing algorithms. Ultimately, what we want from a routing algorithm is for it to be optimal in terms of robustness, scalability, power, and time; however, it will be shown that guaranteed delivery generally comes at the expense of any one of these desirables. This paper will exhibit a progression from routing in static networks to routing in unit distance wireless networks in order to illuminate the reality of the balance between what we want from wireless ad hoc routing algorithms and what we can expect from them. Much of the analysis presented will be on Dijkstra’s algorithm, the Bellman-Ford algorithm, Compass Routing, Face Routing, as well as localized methods to extract planar subgraphs.

Keywords: Wireless Routing, Unit Distance Wireless Networks, Dijkstra’s algorithm, Bellman-Ford algorithm, Compass Routing, Face Routing

Cite this paper: Tzvetalin S. Vassilev, Brian Eades, Wireless Routing in Ad-Hoc Networks, Computer Science and Engineering, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2013, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.5923/j.computer.20130301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The ongoing advancements in wireless technology have allowed for many different devices (old and new) to communicate in a wireless network at a declining cost. While some of these networks may consist purely of stationary devices, mobility is the primary advantage of wireless communication. Thus the underlying mechanisms that dictate how a packet is sent from one device to another should reflect not only our understanding of how wireless mobile devices operate, but also our desire for optimal performance. The representation of networks as geometrical graphs provides the foundation for ingenuity in routing protocols. Graphs provide insight into both the optimal aspects of a routing algorithm as well as its limitations. To this end, a thorough examination of several routing algorithms along with their inherent structures and optimality aspects will be presented, beginning with the classical approach in static networks and ending with methods used in homogenous wireless networks.

2. Classical Approaches

- While it will be shown that the following static routing algorithms are not appropriate for wireless networks in general, the underlying methods and objectives provide the foundation to which several effective routing protocols are based on[1].

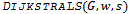

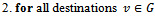

2.1. Link-State Protocol: Dijkstra’s Algorithm

- The algorithm presented below produces the shortest path from a source

to all possible destinations

to all possible destinations  on a directed graph

on a directed graph  with non-negative edge weights

with non-negative edge weights  . Its implementation in networking is known as a link-state algorithm[2, 3]. Let

. Its implementation in networking is known as a link-state algorithm[2, 3]. Let  denote the number of nodes in the graph. Let

denote the number of nodes in the graph. Let  be the total weight of the shortest path from the source

be the total weight of the shortest path from the source  to destination

to destination  . Let

. Let  be the cost of routing from

be the cost of routing from  to

to  (i.e., the sum of all edge weights along the path from

(i.e., the sum of all edge weights along the path from to

to  . Finally, let

. Finally, let  contain the vertices in

contain the vertices in  whose shortest paths have been determined.Algorithm

whose shortest paths have been determined.Algorithm  Input: a graph

Input: a graph  (represented by an adjacency list), non-negative edge weights

(represented by an adjacency list), non-negative edge weights  , and source

, and source  .Output: weight of shortest path from source

.Output: weight of shortest path from source  to all destinations

to all destinations  .

.

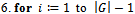

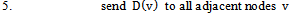

The structure of the above algorithm comes from[2], while a more detailed analysis of its functionality and correctness is outlined in[3]. Lines 6 through 9 are known as relaxing an edge. A total of

The structure of the above algorithm comes from[2], while a more detailed analysis of its functionality and correctness is outlined in[3]. Lines 6 through 9 are known as relaxing an edge. A total of  edges are relaxed, each requiring

edges are relaxed, each requiring  computations, which results in an overall complexity of

computations, which results in an overall complexity of  . The implementation of a binary heap for the priority queue improves the relaxation computation to

. The implementation of a binary heap for the priority queue improves the relaxation computation to  and thus the overall complexity to

and thus the overall complexity to  .Regardless, the implementation of link-state protocols generally requires global state information from the graph. That is, the topology and link-costs are known to every node, which culminates in one exhaustive routing table that is maintained between all nodes. Hence a small change in the topology of the system can propagate into large errors in the routing table. Even with the available global state information, routing loops can still occur; for instance when two nodes

.Regardless, the implementation of link-state protocols generally requires global state information from the graph. That is, the topology and link-costs are known to every node, which culminates in one exhaustive routing table that is maintained between all nodes. Hence a small change in the topology of the system can propagate into large errors in the routing table. Even with the available global state information, routing loops can still occur; for instance when two nodes  and

and  attempt to route through each other to get to a destination

attempt to route through each other to get to a destination  . An example of this event will be provided in the next section, as the directed distance vector routing protocol is also sensitive to changes in topology. Thus the use of Dijkstra’s algorithm in wireless ad hoc networks is ill suited due to its static nature, time-complexity, and the overhead requirements it imposes on a network by requiring global state information.

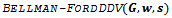

. An example of this event will be provided in the next section, as the directed distance vector routing protocol is also sensitive to changes in topology. Thus the use of Dijkstra’s algorithm in wireless ad hoc networks is ill suited due to its static nature, time-complexity, and the overhead requirements it imposes on a network by requiring global state information.2.2. Directed Distance Protocol: The Bellman-Ford Algorithm

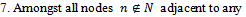

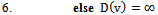

- The directed distance-vector routing protocol is nearly identical to the Bellman-Ford algorithm – but with one modification: the relaxation phase uses an infinite while loop in order to achieve a quiescent state that responds to link-cost changes or updated distance vectors[2].A major distinction between link-sate and directed distance-vector routing algorithms is the amount of information that is available to a given node in a network. The algorithm below uses localized information of a source to calculate the distance vector to each of its neighbours. Once each node has calculated its distance-vector, it is broadcasted to each of their respective neighbours. The result is a minimum weight-spanning tree.Algorithm

Input: a graph

Input: a graph  (represented by an adjacency list), edge weights

(represented by an adjacency list), edge weights  , and source

, and source  .Output: weight of shortest path from source

.Output: weight of shortest path from source  to all destinations

to all destinations  .

.

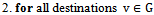

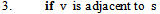

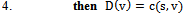

7. while (there exists a link cost change or updated distance vector to some adjacent

7. while (there exists a link cost change or updated distance vector to some adjacent  )9. do: for all

)9. do: for all  ,

,

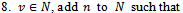

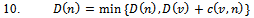

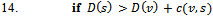

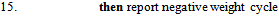

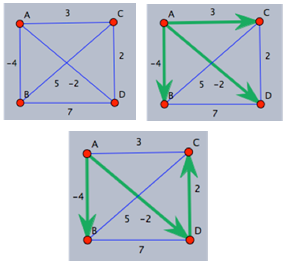

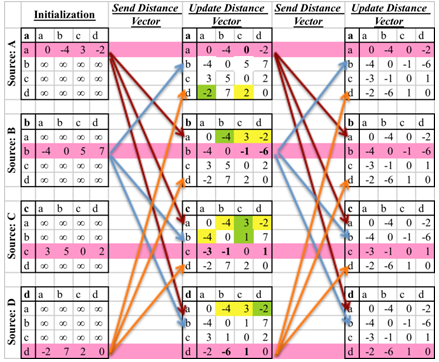

Figure 1 illustrates how the Bellman-Ford algorithm produces the shortest path in the given graph with A as the source. Figure 2 exemplifies the distributive and asynchronous nature of the algorithm where each node maintains its own routing table and sends updated distance vectors to neighbouring nodes.Note that the purpose of lines 14 to 16 is to check for negative weight cycles within the graph. This may be unnecessary if all edge weights are non-negative, but depending on what the routing costs are representing, negative weights may be unavoidable. For instance, they might signify the load carried or removed from a packet as it travels from a source to a destination. It is simply one of many preventative measures against routing loops. Unfortunately, the Bellman-Ford algorithm can converge very slowly, and despite its ability to accept changes in topology it is prone to routing loops. An example of how a link-cost change can result in a routing loop is shown in Figure 3.[2]

Figure 1 illustrates how the Bellman-Ford algorithm produces the shortest path in the given graph with A as the source. Figure 2 exemplifies the distributive and asynchronous nature of the algorithm where each node maintains its own routing table and sends updated distance vectors to neighbouring nodes.Note that the purpose of lines 14 to 16 is to check for negative weight cycles within the graph. This may be unnecessary if all edge weights are non-negative, but depending on what the routing costs are representing, negative weights may be unavoidable. For instance, they might signify the load carried or removed from a packet as it travels from a source to a destination. It is simply one of many preventative measures against routing loops. Unfortunately, the Bellman-Ford algorithm can converge very slowly, and despite its ability to accept changes in topology it is prone to routing loops. An example of how a link-cost change can result in a routing loop is shown in Figure 3.[2] | Figure 3. Example of how a link-cost change can result in a routing loop |

. When A receives the updated distance vector from B, it will now believe that a direct path from B to C does not exist and will therefore route to C directly (as it would have all along if global state information was available).While localized information certainly decreases the overhead costs of routing protocols, it enables errors to propagate from node to node. Despite the existence of preventative measures such as adding poisoned reverse, Dijkstra's algorithm and the Bellman-Ford algorithm are neither robust nor computationally efficient enough to handle the dynamic nature of wireless ad hoc networks. In order to formulate routing protocols that are appropriate for these purposes, desirable structures will be analysed next.

. When A receives the updated distance vector from B, it will now believe that a direct path from B to C does not exist and will therefore route to C directly (as it would have all along if global state information was available).While localized information certainly decreases the overhead costs of routing protocols, it enables errors to propagate from node to node. Despite the existence of preventative measures such as adding poisoned reverse, Dijkstra's algorithm and the Bellman-Ford algorithm are neither robust nor computationally efficient enough to handle the dynamic nature of wireless ad hoc networks. In order to formulate routing protocols that are appropriate for these purposes, desirable structures will be analysed next.3. Structures of Wireless Ad Hoc Networks

- The remainder of the algorithms to be presented are known to work in planar, connected, unit distance wireless graphs. First, a justification for modeling wireless ad-hoc networks in unit distance graphs will be outlined, followed by localized methods to extract planar sub graphs.

3.1. Unit Distance Wireless Graphs

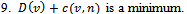

- Let

be a set of

be a set of  points in the Euclidean plane. The unit distance wireless graph of

points in the Euclidean plane. The unit distance wireless graph of  contains all

contains all  points, and edges

points, and edges  such that the distance between

such that the distance between  and

and  is within 1 unit

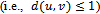

is within 1 unit  [4]. An example of a

[4]. An example of a  on a set of 6 points is illustrated in Figure 4.The reasoning behind using

on a set of 6 points is illustrated in Figure 4.The reasoning behind using  to model wireless networks stems from the concept of broadcast ranges. That is, wireless devices are limited in their ability to communicate with other devices in accordance to their broadcast range. In the

to model wireless networks stems from the concept of broadcast ranges. That is, wireless devices are limited in their ability to communicate with other devices in accordance to their broadcast range. In the  , all broadcast ranges are assumed to be uniform, hence

, all broadcast ranges are assumed to be uniform, hence  can send a packet directly to

can send a packet directly to  if and only if

if and only if  is contained within the circle of radius 1 centered at

is contained within the circle of radius 1 centered at  .Finally, it is entirely reasonable to assume that a wireless device has knowledge of its co-ordinates due to the wide use of Global Positioning Systems.

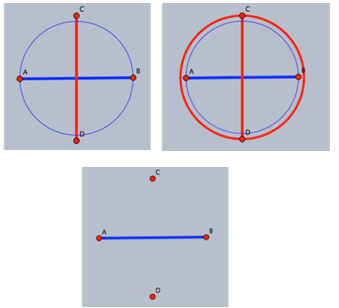

.Finally, it is entirely reasonable to assume that a wireless device has knowledge of its co-ordinates due to the wide use of Global Positioning Systems.3.2. Gabriel Graphs

- Consider a set of

points in the Euclidean plane

points in the Euclidean plane  . The Gabriel circle

. The Gabriel circle  of two points

of two points  is defined as the circle that passes through both points and has the segment

is defined as the circle that passes through both points and has the segment  as a diameter, with the condition that no other point

as a diameter, with the condition that no other point  from

from  lies within

lies within  .

. | Figure 4. of a set of 6 points:  . Each circle has a radius of 1 unit . Each circle has a radius of 1 unit |

,

,  , consists of all

, consists of all  points and edges

points and edges  such that

such that  exists[5]. Figure 5 demonstrates the construction of the Gabriel graph on 3 points.

exists[5]. Figure 5 demonstrates the construction of the Gabriel graph on 3 points. | Figure 5. Gabriel Graph of a set of 3 points:  |

such that the Gabriel graph

such that the Gabriel graph  is non-planar. Then there exists at least one edge intersection between two edges

is non-planar. Then there exists at least one edge intersection between two edges  and

and  . Since

. Since  is a Gabriel edge it follows that neither

is a Gabriel edge it follows that neither  nor

nor  lies inside

lies inside  . Then regardless of the position of

. Then regardless of the position of  or

or  outside of

outside of , the circle

, the circle  will contain at least one of the points

will contain at least one of the points  or

or  . But then

. But then  cannot be a Gabriel edge, which contradicts the supposition. Therefore, the Gabriel graph on a set of points

cannot be a Gabriel edge, which contradicts the supposition. Therefore, the Gabriel graph on a set of points  is always planar. Figure 6 illustrates the proof of the Gabriel graph’s planarity.Finally, given a connected

is always planar. Figure 6 illustrates the proof of the Gabriel graph’s planarity.Finally, given a connected  on a set of points

on a set of points  , the intersection of

, the intersection of  and

and  results in a connected planar subgraph

results in a connected planar subgraph  [5].To prove the connectedness of

[5].To prove the connectedness of  , suppose that

, suppose that  is connected and

is connected and  is disconnected.Then there exists points

is disconnected.Then there exists points  such that they are adjacent in

such that they are adjacent in  but not adjacent in

but not adjacent in  . This necessitates the existence of a third point

. This necessitates the existence of a third point  such that

such that  lies within the Gabriel circle

lies within the Gabriel circle  . But then

. But then

and

and  . Hence there are edges

. Hence there are edges  and

and  resulting in a path from

resulting in a path from  to

to  in

in  (which contradicts the above supposition). Therefore if

(which contradicts the above supposition). Therefore if  is connected, then

is connected, then  is connected as well[5].It follows that a connected planar subgraph can be extracted from any connected

is connected as well[5].It follows that a connected planar subgraph can be extracted from any connected  by having each node in the graph check for the existence of Gabriel circles between itself and its neighbours. Thus, there exists a localized method to extract planar subgraphs which can be accomplished for each point

by having each node in the graph check for the existence of Gabriel circles between itself and its neighbours. Thus, there exists a localized method to extract planar subgraphs which can be accomplished for each point  in

in  time, where

time, where  is the number of neighbouring nodes to

is the number of neighbouring nodes to  [5].

[5].  | Figure 6. Planarity of the Gabriel graph on a set of 4 points:  |

3.3. Delaunay Graphs

- The Delaunay graph is an excellent structure to have within networks as it contains every Gabriel edge. Although the relative neighbourhood graph will not be discussed in this paper, it is worth mentioning that the Gabriel graph contains the relative neighbourhood graph as a subgraph, and the relative neighbourhood graph contains the minimum spanning tree as a subgraph. Hence the Delaunay graph contains many valuable structures as subgraphs. Finally the connectedness and planarity of the Delaunay graph and all its subgraphs can be derived from the idea of “forbidden zones” (e.g., the Gabriel circle between any two points is a forbidden zone for any other point) and using the relationships between the above-mentioned structures. However, this is beyond the scope of this paper and will be left for the interested reader as an exercise. Before defining the Delaunay graph of a set of points

, we must define the convex hull. The convex hull of a set of points

, we must define the convex hull. The convex hull of a set of points  is the smallest enclosing polygon

is the smallest enclosing polygon  comprising of all points

comprising of all points  with the condition that every line

with the condition that every line  is completely contained within

is completely contained within  [6].The Delaunay graph

[6].The Delaunay graph  partitions the convex hull into disjoint triangles with the condition that the circumcircle of each triangle does not contain any other point in

partitions the convex hull into disjoint triangles with the condition that the circumcircle of each triangle does not contain any other point in .

.  is uniquely defined if no 4 points are co-circular[5].

is uniquely defined if no 4 points are co-circular[5]. is dual to the Voronoi diagram which divides the plane into

is dual to the Voronoi diagram which divides the plane into  disjoint regions. Each region is defined by a point

disjoint regions. Each region is defined by a point  such that anything within the region is closer to

such that anything within the region is closer to  than any other point

than any other point  . The Voronoi diagram can be computed in

. The Voronoi diagram can be computed in  time; therefore, due to its duality,

time; therefore, due to its duality,  can be calculated in the same time[6].It has been suggested in[5] to force a wireless network to contain the Delaunay graph by either increasing the transmission rates of the wireless devices or by deploying more radio stations.

can be calculated in the same time[6].It has been suggested in[5] to force a wireless network to contain the Delaunay graph by either increasing the transmission rates of the wireless devices or by deploying more radio stations.4. Routing in Wireless Ad-Hoc Networks

- There are many approaches to routing in wireless ad-hoc networks. An absolute necessity in employable routing protocols is the guaranteed delivery of packets to their destination. Compass Routing and Face Routing can guarantee delivery in certain geometric structures as outlined below.

4.1. Compass Routing

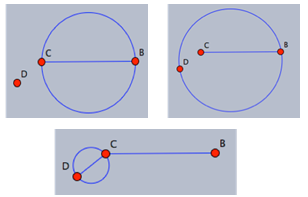

- Given a planar

on a set of points

on a set of points  in the Euclidean plane, suppose that a point

in the Euclidean plane, suppose that a point  intends to send a packet to a destination

intends to send a packet to a destination  (Note if

(Note if  is non-planar, then compute

is non-planar, then compute  ). The forwarding packet must maintain the location of its: current position

). The forwarding packet must maintain the location of its: current position  , destination

, destination , and all nodes

, and all nodes  adjacent to

adjacent to  .Algorithm

.Algorithm  Input: the location of a packet’s: current position

Input: the location of a packet’s: current position  , destination

, destination  , and adjacent nodes

, and adjacent nodes  .Output: arrival of packet at its destination1. Forward packet to neighbour

.Output: arrival of packet at its destination1. Forward packet to neighbour  such that the slope of

such that the slope of  is closest to

is closest to  amongst all

amongst all  2. if

2. if  3. then report arrival of packet at destination, break4. else

3. then report arrival of packet at destination, break4. else  Figure 7 illustrates how this recursive algorithm would proceed on a graph of 8 nodes. Nevertheless, Compass routing is known to work on Delaunay graphs that are uniquely defined, but is still prone to routing loops in graphs with low convexity, and can even fail in convex graphs[5].

Figure 7 illustrates how this recursive algorithm would proceed on a graph of 8 nodes. Nevertheless, Compass routing is known to work on Delaunay graphs that are uniquely defined, but is still prone to routing loops in graphs with low convexity, and can even fail in convex graphs[5]. | Figure 7. Forwarding of a packet from to its destination using Compass routing in the given graph of 8 nodes |

where

where  and

and  are the neighbours of

are the neighbours of  that minimize the clockwise and counter-clockwise angle between all

that minimize the clockwise and counter-clockwise angle between all  and

and  . The packet could theoretically take a very long time to arrive at its destination but in practice, randomized compass routing performs well[5].

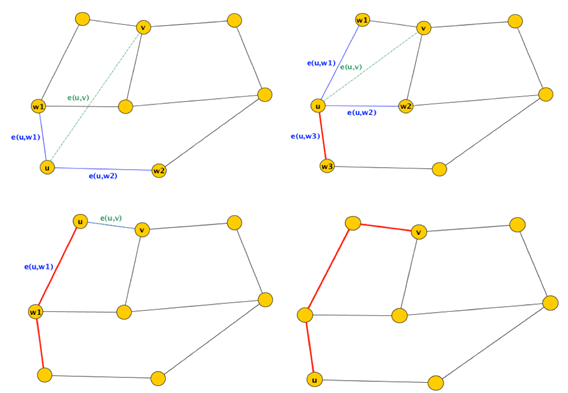

. The packet could theoretically take a very long time to arrive at its destination but in practice, randomized compass routing performs well[5].4.2. Face Routing

- Just as the name suggests, face routing considers the disjoint regions induced on the plane by the edges of the

on a set of points

on a set of points , wherein some edges are considered to appear twice (namely the edge shared between two traversed faces). In addition to a distance

, wherein some edges are considered to appear twice (namely the edge shared between two traversed faces). In addition to a distance  (initially set to 0), a packet must maintain the locations of: its origin

(initially set to 0), a packet must maintain the locations of: its origin , an intermediate point

, an intermediate point  , the destination

, the destination  , and the previous two nodes visited

, and the previous two nodes visited  and

and . This last requirement helps prevent the occurrence of routing loops[4].

. This last requirement helps prevent the occurrence of routing loops[4]. Input: distance

Input: distance  (initially set to 0), and the locations of: its origin

(initially set to 0), and the locations of: its origin  , a point

, a point  (initially set to

(initially set to ), the destination

), the destination  , and the previous two nodes visited

, and the previous two nodes visited  and

and  (initially set to null)Output: arrival of packet to its destination

(initially set to null)Output: arrival of packet to its destination  1. determine the face

1. determine the face  , incident to

, incident to  that is intersected by the line

that is intersected by the line  2. begin the traversal of

2. begin the traversal of  , updating

, updating  and

and  after each edge traversal3. if packet arrives at

after each edge traversal3. if packet arrives at  4. then report arrival of packet at destination 6. else upon intersecting the line

4. then report arrival of packet at destination 6. else upon intersecting the line , calculate the distance

, calculate the distance  from u to this intersection point

from u to this intersection point

9. upon arriving back at

9. upon arriving back at  traverse

traverse  until

until  has been reached

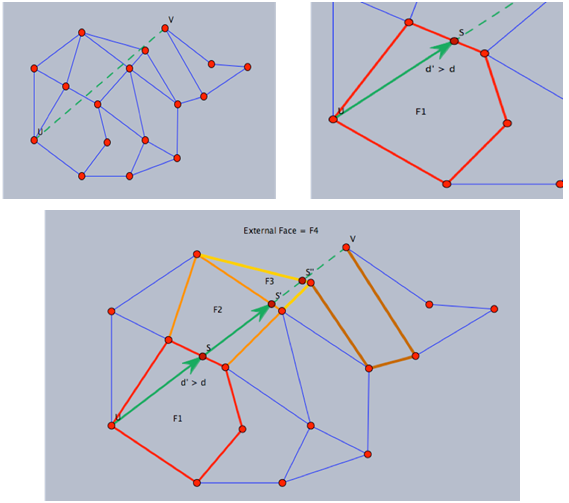

has been reached Refer to Figure 8 for a simulation of face routing on the given graph of 17 nodes.Out of all the algorithms presented, face routing is by far the most robust as it is known to work on all planar networks. Due to the constant amount of memory of the packet, the algorithm handles changes in topology very well. For instance if one of the nodes along the path from

Refer to Figure 8 for a simulation of face routing on the given graph of 17 nodes.Out of all the algorithms presented, face routing is by far the most robust as it is known to work on all planar networks. Due to the constant amount of memory of the packet, the algorithm handles changes in topology very well. For instance if one of the nodes along the path from  to

to  stops transmitting its signal, the packet and its forwarding method is unaffected unless the packet resides at the failed node in question. If this is the case then the packet of will not reach its destination since only one copy of the packet is forwarded from node to node. Aside from this scenario, a packet is also subject to routing loops if a node along the path from

stops transmitting its signal, the packet and its forwarding method is unaffected unless the packet resides at the failed node in question. If this is the case then the packet of will not reach its destination since only one copy of the packet is forwarded from node to node. Aside from this scenario, a packet is also subject to routing loops if a node along the path from  to

to  continually fails and recovers during a face traversal; but this is a highly degenerate case. Finally, each of the edges of a given face is traversed at most twice[4].

continually fails and recovers during a face traversal; but this is a highly degenerate case. Finally, each of the edges of a given face is traversed at most twice[4].5. Conclusions

- At first glance it would appear that the link-state and distance-vector routing protocols are ill suited for wireless ad-hoc networks, but the majority of heuristic protocols used are largely influenced by their methodologies[1]. What is highly undesirable of these methods is the overhead costs associated with maintaining routing table(s).The unit distance wireless graph is a good representation of wireless ad hoc networks in which the wireless devices all have a uniform broadcast range. Of course, there are many cases in which broadcast ranges are not uniform, and there are often environmental factors that can inhibit a transmitter’s signal strength. However this model provides the foundation to which compass routing and more importantly face routing can guarantee delivery.It was suggested in[4] that since nodes within a unit distance wireless graph generally have relatively few adjacent nodes, the greedy quadratic time algorithms are better suited for determining incident edges, as their implementation is simpler. However, the robustness and scalability of face routing is undeniable and should at least be employed as an alternative routing protocol when routing loops persist within a system.Many other on-demand routing protocols like face routing and compass routing require methods to extract planar subgraphs. This paper discussed only the use of the intersection of the Gabriel graph and the unit distance wireless graph

as an alternative to the greedy approach. The relative neighbourhood graph

as an alternative to the greedy approach. The relative neighbourhood graph  is another nice geometric structure that can be derived in the same amount of time and is equally useful in the formation of localized routing algorithms[2, 6].

is another nice geometric structure that can be derived in the same amount of time and is equally useful in the formation of localized routing algorithms[2, 6].ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Dr. Vassilev’s research is supported by NSERC Discovery Grant.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML

with as the source. The green arrows represent the shortest path from

with as the source. The green arrows represent the shortest path from  to all other nodes. The change in shortest path reflects the iterative updates in distance vectors

to all other nodes. The change in shortest path reflects the iterative updates in distance vectors

to

to