-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics

p-ISSN: 2163-1433 e-ISSN: 2163-1441

2026; 14(1): 1-5

doi:10.5923/j.cmd.20261401.01

Received: Dec. 19, 2025; Accepted: Jan. 6, 2026; Published: Jan. 9, 2026

Dentistry in Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome: Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction, Occlusal Instability, and Conservative Management

Christopher Brown DDS , MPS

Director of Innovation, Neuraxis Inc, Carmel, In. USA

Correspondence to: Christopher Brown DDS, MPS, Director of Innovation, Neuraxis Inc, Carmel, In. USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

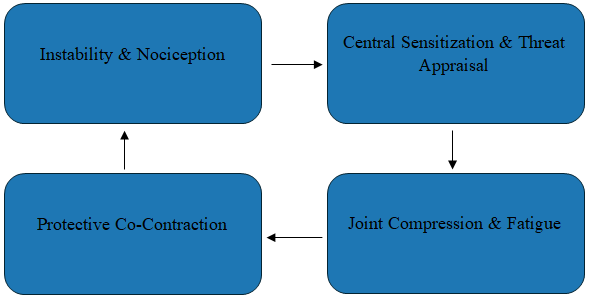

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) comprises a group of heritable connective tissue disorders caused by abnormalities in collagen structure or biosynthesis. The 2017 international classification recognizes 13 subtypes with variable genetic and clinical features. [1] Hypermobile EDS is the most prevalent subtype and is most commonly associated with temporomandibular disorders, reflecting generalized joint hypermobility and connective tissue laxity. [2] Classical and vascular subtypes are less frequently associated with TMD but may influence dental and temporomandibular management because of tissue fragility and altered healing responses. [1] Across subtypes, impaired connective tissue integrity contributes to joint instability and abnormal biomechanical loading, providing a mechanistic basis for temporomandibular dysfunction in affected individuals. [1] Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are common in hypermobile phenotypes and may present as capsular laxity with recurrent subluxation, disc displacement, myofascial pain, and dynamic occlusal changes. [6,7,16] This manuscript provides a clinically oriented review of EDS-associated TMD emphasizing diagnostic pitfalls, conservative treatment sequencing, and stabilization orthotic design tailored to hypermobile patients. Using contemporary conceptual models of TMD that integrate instability, neuromuscular control, central pain processing, and sleep physiology. [7,10,11,12] Conservative care combining education, graded rehabilitation, sleep optimization, and stabilization orthotics—preferably lower-arch orthotics with careful monitoring—can reduce symptoms while minimizing iatrogenic occlusal change. [18,20,21] Recognizing the connective tissue phenotype and avoiding irreversible occlusal interventions during symptomatic phases are central to safe TMD management.

Keywords: Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Hypermobility, Temporomandibular disorders, Occlusal orthotic, Occlusal instability, Myofascial pain, Conservative management [16,11]

Cite this paper: Christopher Brown DDS , MPS , Dentistry in Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome: Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction, Occlusal Instability, and Conservative Management, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2026, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20261401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

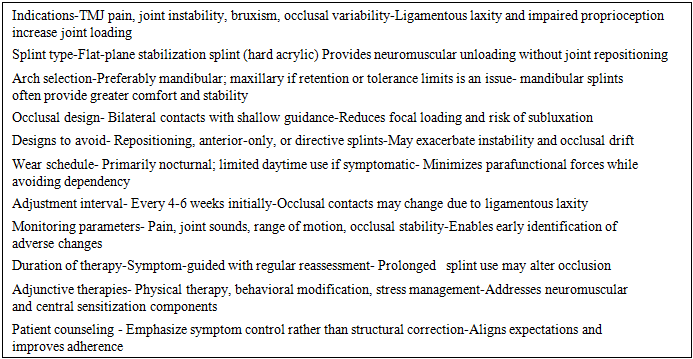

- Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome alters the mechanical environment in which the masticatory system operates. Capsular tissues, ligaments, and tendons demonstrate altered tensile properties, and many patients exhibit impaired proprioception and reduced ability to stabilize joints at the end of the normal range of motion. [1,2,4] In the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), stability is achieved through a balance of passive restraint and active neuromuscular control. When passive restraints are compliant, the burden of stability shifts toward sustained muscle co-contraction. While protective in the short term, this response can become maladaptive, producing muscular fatigue, myofascial pain, and increased joint compression. [3,8,9]Temporomandibular disorders represent a spectrum involving the masticatory muscles, the TMJ, the capsule, and associated structures. Contemporary frameworks emphasize interacting drivers—nociceptive input, motor control patterns, central pain processing, psychosocial context, and sleep physiology—rather than a purely occlusal etiology. [7,10] In hypermobile phenotypes, instability is often a dominant driver. Patients may report an occlusion (bite) that feels different across several days or even within the same day, a feature that can be misinterpreted as primary occlusal pathology if connective tissue–mediated variability is not recognized. [8,21,22]This presents a practical approach focused on pathophysiology, diagnostic strategy, and conservative management. Splint therapy is integrated as a vital aspect of a staged plan, with emphasis on reversibility, monitoring, and risk management.

2. Methods

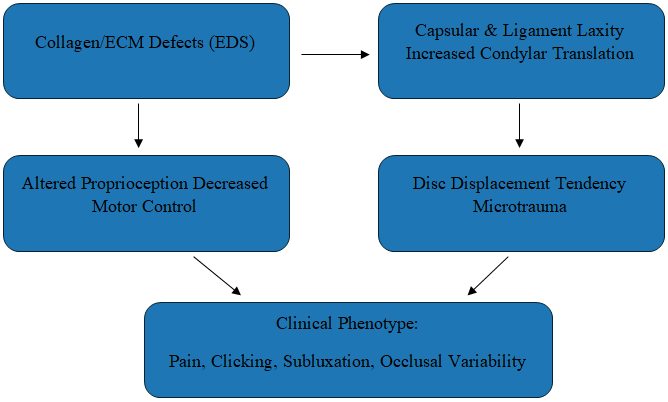

- This review integrates consensus statements and widely cited peer-reviewed literature addressing EDS classification and clinical features, [12] TMD diagnostic criteria, [6] contemporary conceptual models of TMD, [7,10] and conservative interventions including rehabilitation and occlusal appliance therapy. [18,20] The objective is suggesting a conservative sequencing pathway for dental clinicians managing patients with hypermobility or diagnosed EDS.

3. Pathophysiology of TMJ Dysfunction in EDS

| Figure 1. Neuromuscular Loop Sustaining Hypermobile TMD |

| Figure 2. Drivers of TMJ Instability in EDS |

4. Clinical Presentation

- Presentations vary by EDS subtype and comorbidity profile. Common TMJ features include clicking or popping, intermittent locking, pain with chewing, and a sense that the joint “slips” with wide opening. [6,9,17] Pain may be localized to the preauricular area or experienced predominantly as diffuse myofascial pain.Variability in intensity and areas of symptoms is not uncommon. Symptoms and occlusal contacts may change daily with patients may report a bite that feels different after sleep or prolonged function. This variability increases the risk of iatrogenic harm from irreversible occlusal adjustments based on single time-point observations. [8,21,22] Headaches and otologic complaints may coexist even when primary pathology is muscular or instability-driven. [9]In addition to TMD, generalized muscular fatigue, widespread pain, anxiety, and sleep disruption are common and influence tolerance for dental procedures. Recognizing these features supports shorter appointments, ergonomic positioning, and clear post-procedure guidance. [3,23,25]

5. Differential Diagnosis and Diagnostic Considerations

- The differential diagnosis for TMD and peri-auricular pain includes odontogenic disease, cracked tooth syndrome, periodontal pathology, sinus disease, neuralgias, salivary gland disorders, and primary headache syndromes. Utilizing a progressive approach to TMD provides a standardized approach to differentiate myalgia, arthralgia, and disc displacement patterns. [6,9,13]Screening for hypermobility using history prompts and brief tools can identify patients who may warrant formal evaluation for EDS. [25] Clinical examination should assess range of motion, deviation on opening, end-feel, joint sounds, and reproducibility of symptoms with loading and palpation. Direct muscle palpation assists in distinguishing myofascial pain from primary joint pain. [9,13]Imaging is important to assist with a differential diagnosis. An MRI can assess disc position, effusion, and other soft tissues within the joint while panoramic and CBCT characterizes osseous remodeling. In hypermobile patients, imaging must be interpreted in the context of neuromuscular and central mechanisms, as symptom intensity often does not correlate with structural findings. [7,24]

6. Management Strategies

| Figure 3. Conservative treatment algorithm for EDS-associated TMD |

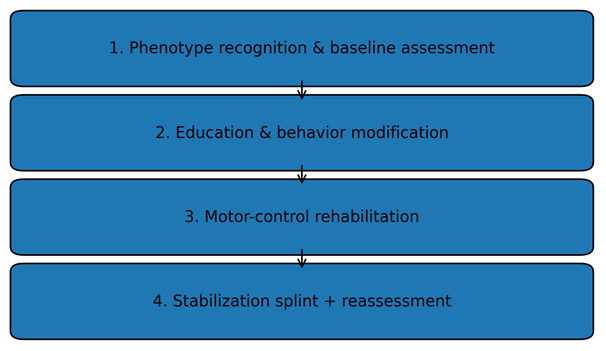

7. Splint Therapy in EDS-Associated TMD

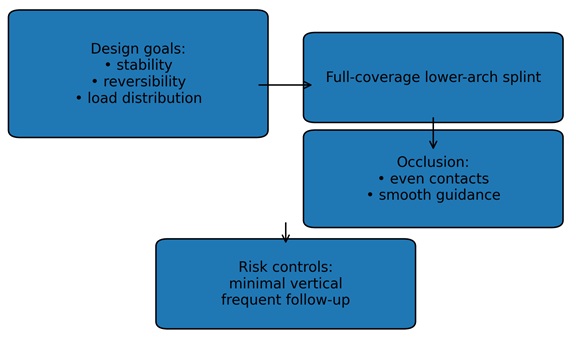

| Figure 4. Lower-arch stabilization splint design principles |

|

8. Discussion

- EDS challenges purely structural explanations of TMD. Capsular laxity, altered proprioception, central sensitization, and sleep-related motor activity interact to produce a variable phenotype in which irreversible occlusal interventions can be harmful. [3,7,10,25] Structured conservative care with monitoring aligns with contemporary standards and minimizes iatrogenic risk. [18,21]Objective Outcome MeasurementsSuccess of treatment can be best measured by the following:1. Mandibular ROM ( range of motion) 2. Report of findings of soft tissue palpation3. Review of patient history4. Review of medication consumption related to pain5. Occlusal wear patterns on the orthoticPatients are often seen on a 4-6 week period at the beginning of active treatment.Interdisciplinary coordination is often beneficial given cervical involvement, migraine, dysautonomia, and widespread pain. Documenting objective outcomes and titrating reversible interventions provides a pragmatic pathway for complex patients.LimitationsThis review has several limitations. First, much of the available literature on dental and temporomandibular manifestations of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome consists of case reports, small observational studies, and expert opinion, which limits the strength and generalizability of conclusions. Second, EDS represents a heterogeneous group of disorders with varying genetic mechanisms and clinical severity; many studies do not clearly distinguish among subtypes, making it difficult to attribute findings to specific forms of the condition. Third, standardized diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders and dental instability are inconsistently applied across studies, introducing variability in reported prevalence and treatment outcomes. Finally, there is a relative paucity of prospective, controlled trials evaluating conservative dental interventions in EDS populations, underscoring the need for higher-quality, subtype-specific research to inform evidence-based clinical guidelines.

9. Conclusions

- EDS-associated TMD is best approached as an instability–pain–motor control syndrome. A conservative, staged plan incorporating stabilization orthotic therapy, rehabilitation, and sleep/stress optimization can reduce symptoms while preserving long-term function. [16,18,21]

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML