-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics

p-ISSN: 2163-1433 e-ISSN: 2163-1441

2021; 11(1): 1-4

doi:10.5923/j.cmd.20211101.01

Received: Feb. 6, 2021; Accepted: Mar. 1, 2021; Published: Mar. 15, 2021

A Case on Cardiomyopathy in Children Improved with Medical Treatments

Md. Shahariar Khan1, Manjur Hossain2, Tania Hussain1, Syed Moosa M. A. Quaium1, Md. Rahimullah Miah3

1Department of Paediatrics, Northeast Medical College & Hospital, Sylhet, Bangladesh

2Directorate General of Family Planning, Dhaka, Government of Peoples Republic of Bangladesh

3Department of Information Technology in Health, Northeast Medical College & Hospital Pvt. Ltd, Sylhet, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Md. Shahariar Khan, Department of Paediatrics, Northeast Medical College & Hospital, Sylhet, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Cardiomyopathy is a severe disease. There's generally no cure for the situation in children, but it can be treated. Way of life changes, medicines, and surgically implanted devices can help to manage symptoms and occasionally stop the disease from getting worse. In serious cases, a heart transplant may be needed. Cardiomyopathy is the most common cause for heart transplants in children. If the condition isn't managed, it can lead to a life-threatening arrhythmia, heart valve problems, heart failure etc. The case study illustrates a 10 months old baby presented with recurrent respiratory infection. After thorough clinical examination, all necessary investigation including chest X-ray, ECG, Color Doppler Echocardiography have been done and diagnosed as dilated cardiomyopathy with pneumonia and heart failure. The child was treated with antibiotics, diuretics, digoxin, ACE inhibitors, vitamin with minerals and also relevant drugs to relieve other symptoms. Then the patient discharged with a maintenance dose of these drugs with regular follow-up. After 6 months, the patient was improved clinically and also all investigation reports showed normal findings.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Recurrent, Respiratory infection, Echocardiography

Cite this paper: Md. Shahariar Khan, Manjur Hossain, Tania Hussain, Syed Moosa M. A. Quaium, Md. Rahimullah Miah, A Case on Cardiomyopathy in Children Improved with Medical Treatments, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 11 No. 1, 2021, pp. 1-4. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20211101.01.

1. Introduction

- Cardiomyopathy (CMP) in children is an unusual disease with a yearly incidence of 1.1 to 1.5 per 100 000 [1]. There are many types of cardiomyopathy, out of which Dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies are more common [1]. The commonest cause of Pediatric cardiomyopathies is yet genetic [2]. About 40% of children with symptomatic cardiomyopathy go through heart transplantation or die within the first 2 years after identification [2]. Children with CMP are an uncommon but occasionally lethal myocardial disease affecting the Paediatric age group and also can occur at any age [3]. CMP is a heterogeneous illness caused by a functional defect of the cardiac muscle and is a common reason of heart failure in children [4]. Few cases of cardiomyopathy in children still remain with an undetermined or idiopathic etiology [5]. Dilated CMP (DCMP) is the most frequent form of CMP globally which is mostly genetically inherited and also 20% to 48% have a family history of the illness [4]. Additionally, inflammatory disorders such as myocarditis, toxic agents can cause DCMP [4]. The outcome of cardiomyopathy in children is not good, particularly in those with a cardiomyopathy of a recognized etiology, which showed a higher possibility of death or heart transplantation [6]. A patient with DCM may be cured totally or die [7]. It is essential to differentiate children with lonely cardiomyopathy from those with systemic disease because there are extra management considerations and medical desires in the latter people [8]. Recent technical developments in genetic studies on CMP have elucidated the potential benefit of genetic testing in the identification and in understanding the path genetic basis of hereditary CMP [4]. Estimation of myocardial recognition of pre-clinical DCM could significantly decrease morbidity and mortality by allowing early initiation of cardio protective therapy [9].

2. Case Report

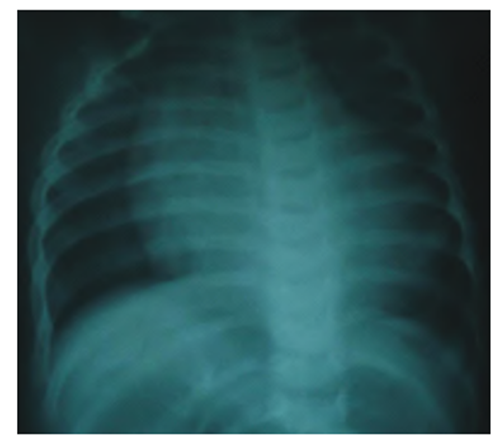

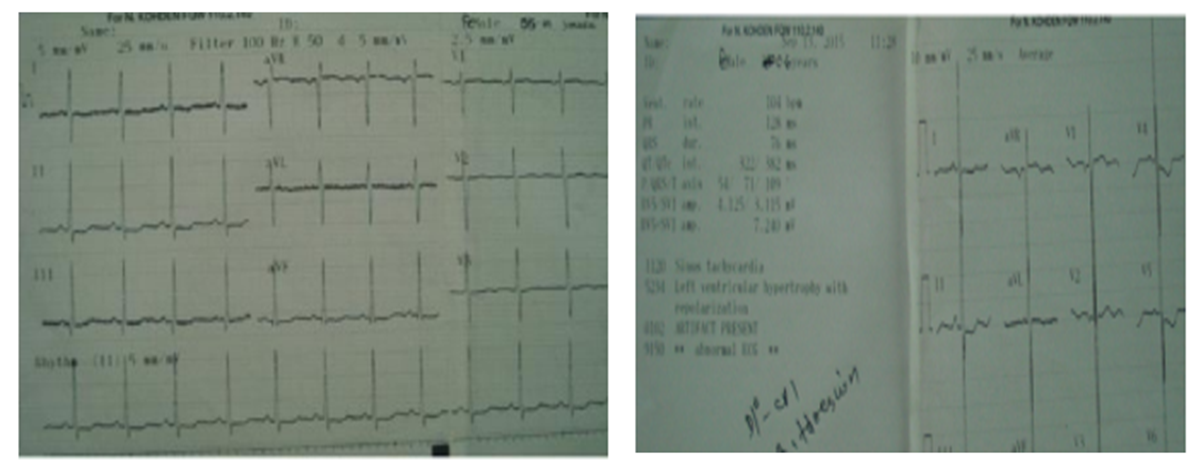

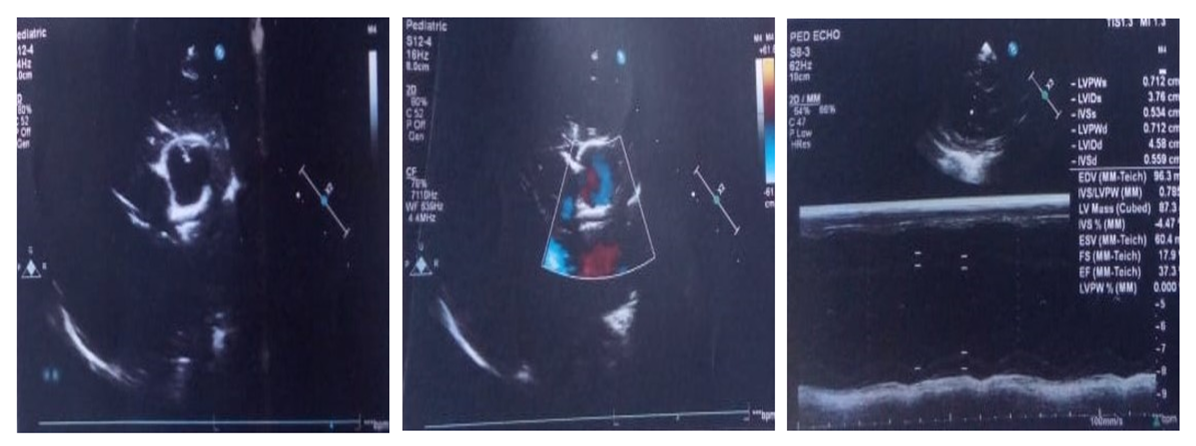

- A ten months old baby girl (weight 7.5 kg) got admitted to the department Paediatrics in North East Medical College Hospital, Sylhet, Bangladesh on 20 May, 2020. She suffered in fever, cough and respiratory distress for five days with feeding difficulties. There was no history of cyanosis, convulsion or unconsciousness. She was exclusively breast fed and proper weaning as well as immunized as per expanded program on immunization (EPI) schedule. She also had a history of recurrent respiratory infection within the last 6 months and received medical treatment locally, but not improved properly. At present examination, heart rate was 160 beats/minute; respiratory rate was 66 breaths/minute with chest in drawing. Apical impulse was lateral to mid clavicular line in 6th intercostal space. Heart sound was muffled, precordium was slightly bulged and there was tender hepatosplenomegaly. Percent saturation of oxygen was 88%. On auscultation of the chest, breath sound was vesicular with prolonged expiration, Ronchi and crepitation were present all-over the chest. Heart sound was normal with no added sound. The patient was diagnosed clinically as Pneumonia with Heart Failure. Chest X-ray revealed cardiomegaly shown in Figure 1 and ECG revealed left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) shown in Figure 2. Echocardiography showed global hypokinesia of the left ventricle (LV) with poor function. LV was hugely dilated with ejection fraction (EF) - 37%, which as shown in Figure 3. CBC (Complete blood count) showed neutrophilic leukocytosis. So, overall diagnosis was dilated cardiomyopathy with pneumonia and heart failure. The Patient was treated with bed rest in head-up position, O2 inhalation, nebulization with salbutamol, injectable Antibiotics such as Ceftriaxone and Amikacin, Injection Frusemide diuretics, Digitalization with Injection Digoxin, Anti-hypertensive agents e.g. ACE inhibitors and other supportive treatments including fluid and nutrition supplements in Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). Then gradually the patient was improved clinically with EF 46% and discharged after one week with maintenance dose of oral Digoxin, Diuretics, ACE inhibitors and other additional supplementary drugs for health and nutrition. With regular 3 monthly follow up her EF raised up to 60% and 72% subsequently with no other abnormalities in other examinations and investigations.

| Figure 1. CXR of Patient showing cardiomegaly |

| Figure 2. ECG showing normal sinus rhythm and LVH |

| Figure 3. Echocardiography showing dilated LV and poor LV function |

3. Discussion

- Among all types of cardiomyopathy in children, DCM is more common and it’s epidemiology and medical causes are remaining still indistinct [10]. DCM is a disorder of heart muscle and affects ventricular systolic or diastolic function or both [10]. It is a myocardial dysfunction and characterized by dilated left ventricle (LV) and systolic dysfunction that usually results in congestive cardiac failure [11-13]. This is also the most frequent cause of cardiac transplantation [10]. In infants and older children myocarditis is the more common cause of cardiomyopathy and heart failure. But comparatively very little information has been published on the frequency of DCM [10]. A study showed the occurrence of DCM as 0.56 cases per 100,000 per year which is 10 times higher than adults. Boys have a higher prevalence than girls and blacks have a higher rate than whites [14-16]. Infants are 13 times more affected than older children. Most common cause of DCM in infants includes idiopathic, secondary to viral myocarditis, inborn error of metabolism and lack of thiamine and carnitine [10]. CCF is common in 71% cases of DCM and connected with myocarditis and idiopathic varieties [11]. Maximum children with DCM usually die within the first two years of life. Transplantation is the ideal definite treatment but not yet possible in our country. One-third of patients die, one-third cure with therapy, and the rest one third survive with ongoing treatment throughout life. Early diagnosis, risk estimation, latest therapy needs to be established for children with Cardiomyopathy to prevent early death and avoid the need for transplantation [17-20].

4. Conclusions

- In inference, cardiomyopathy is an unusual serious group of disorders of the heart that stands as a frequent cause of heart failure. The disease is the most common cause of heart transplantation in children. The primary cause of Cardiomyopathy is unknown in the majority of the cases of children. The prognosis in individual patient is variable. It depends upon proper and timely diagnosis, identification of specific causes and optimum medical management of heart failure and cardiac transplantation in some selected cases. The case study reviews advanced medical treatments with drugs and proper follow up can improve the physical condition as well as cure of this disease. The study will provide future research trajectory of a novel approach in children with cardiomyopathy.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML