-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics

p-ISSN: 2163-1433 e-ISSN: 2163-1441

2019; 9(2): 36-40

doi:10.5923/j.cmd.20190902.03

Cognitive Function in Rheumatoid Arthritis Female Patients: A Prospective Cohort Study

Hend G. Kotb1, Rasha Sobhy El Attar2, Hemmat Ahmed Elabd3, Bassma Mohammed Mohammed Ali El Nagger3, Manal Hafez Maabady2

1Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

2Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

3Department of Physical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

Correspondence to: Hend G. Kotb, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

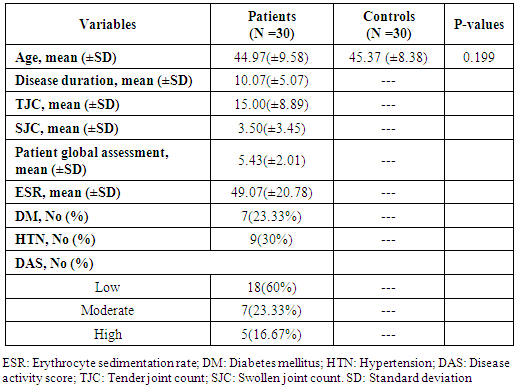

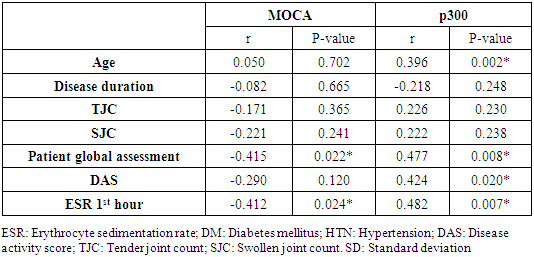

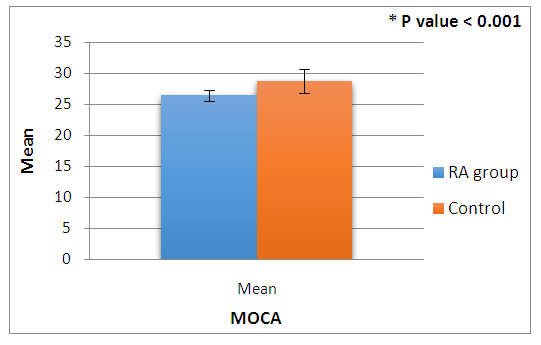

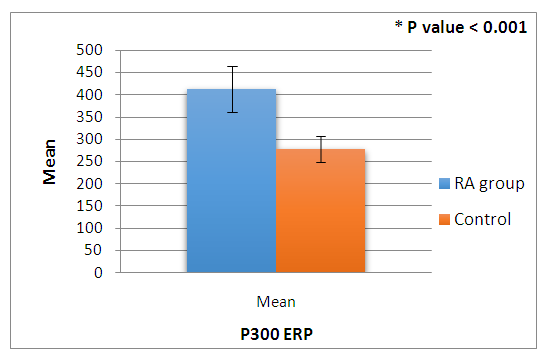

Aim: To assess the cognitive functions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and its correlation with patients’ characteristics. Methods: We conducted a prospective cohort study that included 30 adult females with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). We collected the following data from eligible participants: demographic characteristics, disease duration, drug intake, disease activity measured by the disease activity score in 28 joints (DAS28), visual analogue scale (VAS) for global pain assessment, and cognitive function assessment findings.The cognitive assessment was conducted using Montreal cognitive assessment scale (MOCA) and p300 event related potential (ERP). Results: The mean ages of the included patients and control group were 44.97 (±9.58) years and 45.37 (±8.38) years, respectively (p=0.119). In addition, the mean patient global assessment and DAS28 was 5.43 (±2.01) and 5.31(±1.36), respectively. The primary outcome of the present study, showed that the mean MOCA score in patients with RA was 26.43 (±1.92), compared to 28.8 (±0.88) in control group. Similarly, there was a statistically significant difference in p300 ERP between patients with RA and control 413.87(±51.22) versus 278.9 (±29.7) p <0.001). The correlation analysis showed that the p300 ERP values correlated positively with DAS28 (r =0.424, p =0.02), age (r =0.396, p =0.002), and ESR (r =0.482, p =0.007). On the other hand, the MOCA score correlated negatively with patient global assessment scale (r= -0.415, p =0.022). Conclusion: In conclusion, cognitive dysfunction represent another cause of burden in RA. The present study shows that patients with RA had significantly lower cognitive performance and processing than the general population.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, Cognitive function, Montreal Cognitive Assessment

Cite this paper: Hend G. Kotb, Rasha Sobhy El Attar, Hemmat Ahmed Elabd, Bassma Mohammed Mohammed Ali El Nagger, Manal Hafez Maabady, Cognitive Function in Rheumatoid Arthritis Female Patients: A Prospective Cohort Study, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 9 No. 2, 2019, pp. 36-40. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20190902.03.

1. Introduction

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is one of the most commonly encountered autoimmune diseases worldwide which affects up to 1% of the global population, with substantial geographic variations [1]. The condition is a chronic inflammatory disease of the connective tissue that is characterized by period of acute exacerbation and remission [2]. Although the exact pathogenesis of RA is till poorly understood, the current body of evidence shows that the disease is initiated by significant alteration in the function of both innate and adaptive immune system with consequent production of autoantibodies, these autoantibodies target wide range of molecules and key cells leading to chronic inflammatory state [3]. This autoimmune and inflammatory cascades were reported to be precipitated by wide range of genetic and environmental factors [4]. RA primarily affects the joint with synovial hyperplasia and bone destruction; typically, patients with RA present with bilateral, polyarticular, affection of small joints in the form of pain, swelling, and morning stiffness [5]. Moreover, advanced disease may be associated with extra-articular systemic involvement such as rheumatoid nodules, pleural diseases, mesangial glomerulonephritis, and more seriously vasculitis [6]. It was also reported that patients with active and severe RA have an increased risks of death than general population [7]. Therefore, RA represent a global socioeconomic burden and a leading cause of disability and mortality. However, with the introduction of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), the prognosis of RA appears to be improved in the recent years [8].On the other hand, central nervous system (CNS) involvement is a rare, but serious, complication of RA as a sequence of the diffuse vasculitis (rheumatoid vasculitis syndrome). Patients with RA may develop one the different types of peripheral neuropathies may occur [9]. Similarly, sever affection of cervical joint with pannus formation may result in cervical myelopathy in RA patients [10]. Recently, a growing body of evidence has shown that patients with RA are at increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and neuropsychiatric manifestations; previous reports demonstrated that patients with RA exhibited defective attention, mental flexibility, verbal function, and memory defect [11]. This significant impairment in cognitive function in RA appear to affect the activities and quality of life of the patient as well. It was reported that RA patients with cognitive impairment had lower score of well-being and were more likely to develop depression and/or anxiety [12,13]. Thus, proper evaluation of cognitive function in RA is critical to improve the clinical and functional outcomes.Nevertheless, the currently published literature shows scarcity regarding the extent and impact of cognitive dysfunction in RA patients. Therefore, we conducted the present prospective study to assess the cognitive functions in patients with RA and its correlation with patients’ characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

- We followed the recommendations of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement during the preparation of the present study [14]. The present study run in concordance with (the Declaration of Helsinki principles) and (the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal). The study’s protocol gained the approval of the local ethics and research committee of faculty of Medicine for girls Al-Azhar University. Study Design and Patients selection:We conducted a prospective cohort study at Internal medicine department of Al-Zhraa University Hospital, through the period from July 2017 to October 2018. Thirty adult females (≥ 18 years old) with established diagnosis of RA and currently treated with DMARDs were recruited from Internal medicine and rheumatology outpatient clinics of Al-Zhraa University Hospital. The diagnosis of RA was done in concordance with (2010) American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism criteria for RA [15], for at least 5 years disease duration. In addition, 30 healthy age-matched females, who had no history of autoimmune disorder, were included as a control group, all patients and control individuals have fair family support, and had no history of any depressive symptoms.A non-probability convenient sampling method was utilized to enroll eligible participants. Written informed consents were obtained from eligible participants prior to study enrollment.Data collection:We collected the following data from eligible participants: demographic characteristics, disease duration, drug intake, disease activity measured by the disease activity score in 28 joints (DAS28) [16], visual analogue scale (VAS) for global pain assessment, and cognitive function assessment findings.Disease Activity Assessment:The disease activity was conducted using DAS28 score. The DAS28 is a simple, reliable, version of the original DAS44 score which produces a composite score after assessment of four domains: the number of swollen joint, number of tender joint, ESR level, and global assessment of health. The final composite score is then calculated.A score of greater than 5.1 is considered as high disease activity, between 3.2 and 5.1 is considered moderate disease activity, and less than 3.2 is considered as low disease activity [16].Cognitive Assessment:The cognitive assessment was conducted at neurology departments of Al-Zhraa University Hospital. All patients and control were subjected to applied questionnaire Montreal cognitive assessment scale (MOCA) [17], and p300 event related potential (ERP) for cognitive assessment [18]. The MOCA scale is a 30-question test that assessed the following aspects of cognitive function: orientation, short-term memory/delayed recall, executive function/visuospatial ability, language abilities, abstraction, animal naming, and attention. The MOCA develop a composite score that ranges from zero to 30 with lower scores denote more impaired function [19]. Auditory p300 ERP was performed using Neuron Spectrum 5 set. The active electrode was placed on cortical zone (CZ), reference electrode on ipsilateral mastoid process and Ground electrode on frontal zone according to the international 10-20 electrode placement system. P300 was recorded using an oddball paradigm. Two tones were presented in a random series at a rate of 0.5/sec, a frequent tone (1000 Hz) in 80% of testing time, and a target tone (2000 HZ) randomly in 20% of testing time with 60 db intensity of both and subjects were learned to count the infrequent tone. One hundred stimuli were collected in each run. Stimuli were presented on the right ear with distracting sound in the other ear. The ERP was filtered from 0.1-30 Hz. Processing of ERP was done by individual and automatic identification of the highest positive deflection between 250 and 500msec and measuring the latency of p300.Study’s Outcomes:The primary outcome in the present study was to quantify the cognitive impairment in patients with RA. The secondary outcome was to correlate between cognitive function and patients characteristics.Statistical Analysis:Data entry, processing, and statistical analysis were carried out using Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, NY, and the USA) and SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 22 for Microsoft Windows. Quantitative data were described in terms of mean ± standard deviation (± standard deviation [SD]), while qualitative data were expressed as frequencies (number of cases) and relative frequencies (percentages). Comparisons between quantitative variables were done using unpaired Student’s t-test for parametric data or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test for non-parametric data. Chi-square test was performed for categorical variables. A probability value (p-value) less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

- The present study included 30 patients with RA and a similar number of age-matched controls. The mean ages of the included patients and control group were 44.97±9.58 and 45.37±8.38 years, respectively (p =0.119). The mean disease duration of the included patients was 10.07±5.07 years. In addition, the mean patient global assessment and DAS28 was 5.43±2.01 and 5.31±1.36, respectively. Eighteen patients (60%) showed low disease activity, 7 patients (23.33%) showed moderate disease activity, and 5 patients (16.67%) showed high disease activity. All patients were on synthetic DMARDs. Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the included participants.

|

|

| Figure 1. The MOCA results in 30 female patients with RA and 30 normal female subjects |

| Figure 2. The P300 ERP results in 30 female patients with RA and 30 normal female subjects |

4. Discussion

- There is a growing body of evidence that there is affection of the cognitive function in RA patients and its association with disease severity, however there is no consensus regarding the exact impact of RA on the cognitive function of the patients. In the present study, we found that patients with RA exhibited more decline in cognitive function, compared to healthy controls. The results showed that the patients with RA had statistically significant lower MOCA and p300 ERP values than the control group. Moreover, the p300 ERP correlated significantly with disease severity, as assessed by DAS28 and ESR; similarly, the MOCA score correlated significantly with patient global assessment scale.MOCA score is a rapid screening tool for assessment of cognitive function that yielded high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of cognitive performance decline. The score assessed mainly seven cognitive abilities which are visuospatial/executive function, naming, episodic memory, attention, language, abstraction, and orientation [17]. Mild cognitive impairment is suggested at a score of less than 26, or more recently 23 [19]. In the presented study, we found that RA patients had significantly lower score than the age-matched healthy controls, which donates a lower cognitive performance in RA. Moreover, the MOCA correlated negatively with disease severity assessed by global patient assessment. Similarly, Meade and colleagues (2018) reported in their systematic review that patients with RA had statistically significant lower scores of cognitive function tests compared to control group, the cognitive function correlated significantly with age and disease severity as well [11]. Another longitudinal cohort study reported that almost one third of RA patients had cognitive impairment, which correlated significantly with disease severity and educational level [20]. Bartolini and colleagues (2002) also reported that the cognitive dysfunction was prevalent in RA patients; in addition, cognitive dysfunction was also associated with hypoperfusion of brain and increased white matter alterations [21].On the other hand, auditory p300 ERP is a reliable indicator of cognitive processing and higher cortical function, previous reports demonstrated that p300 ERP can significantly indicate impairments in different neuropsychiatric functions, mainly processing speed, attention and memory performance [22]. In the present study, we found that patients with RA had significantly higher latency in p300 ERP than the control group, the p300 ERP values correlated significantly with disease severity as well. In concordance with our findings, Hamed and colleagues (2012) reported that patients with RA had significantly abnormal p300 latency and amplitude [23]. Another cross-sectional study on 53 women reported that the average P300 amplitudes were found to be considerably lower (P < 0.05) in the RA group compared to the control group [24].The exact pathogenesis of cognitive dysfunction in RA is still unclear, however, different theories have been proposed. It is well known that the cognitive function is significantly impaired in case of systematic inflammation or ischemic condition, while RA is a chronic inflammatory diseases that is associated with increased risk of vasculitis and ischemic heart disease [25,26]. Another explanation is the chronic pain and stress presented in RA, it was previously reported that the chronic pain is a significant contributor to the pathological changes occurring to the brain function [27]. The prolonged use of oral glucocorticoid in RA may precipitate to cognitive impairment as well, excessive circulatory levels of corticosteroids were observed to be associated with cognitive impairment in various disease states [28].We acknowledge that the present study has a number of limitations. The study included a small number of patients and the power analysis was not planned prior to study enrollment. Moreover, the study was a single-center experience. Such factors may affect the generalizability of our findings. Moreover, patient-centered and long-term outcomes were not utilized in the present study.In conclusion, cognitive dysfunction represent another cause of burden in RA. The present study shows that patients with RA had significantly lower cognitive performance and processing than the general population, which correlates significantly with diseases severity. Therefore, evaluation of cognitive dysfunction in RA patients is important to develop targeted interventions to decrease adverse effects on health status. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to assess its diagnostic utility and therapeutic potentials.

Conflict of Interest

- All authors confirm no financial or personal relationship with a third party whose interests could be positively or negatively influenced by the article’s content.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML