-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics

p-ISSN: 2163-1433 e-ISSN: 2163-1441

2018; 8(1): 14-20

doi:10.5923/j.cmd.20180801.03

High Proportion of Abnormal Semen Characteristics among Saudi Infertile Couples

Wardah Alasmari 1, Fawaz Edris 2, Zainab Albar 1, Abdulrahim Gari 2, Mamdoh Eskandar 3, Mohammed Al Fageah 4, Shamsuldin Zawawi 4

1Department of Human Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Umm al Qura University, Makkaha, Saudi Arabia

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Umm al Qura University, Makkaha, Saudi Arabia; Assisted Conception Unit at the International Medical Centre, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

3Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology College of Medicine, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia

4Faculty of Medicine, Umm al Qura University, Makkaha, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Wardah Alasmari , Department of Human Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Umm al Qura University, Makkaha, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

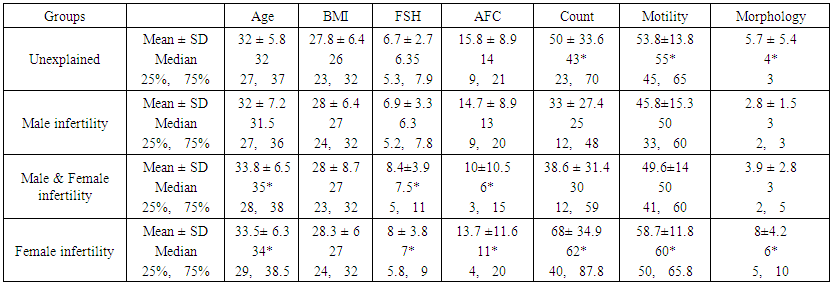

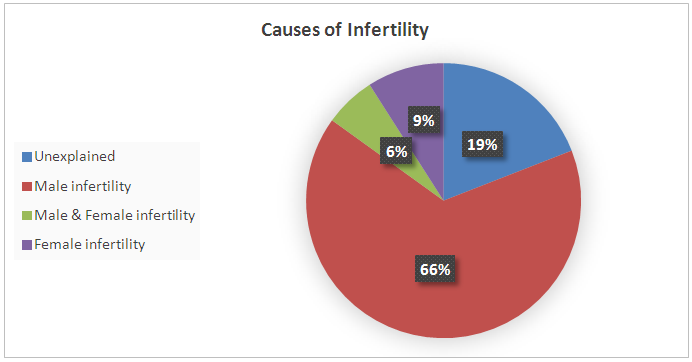

Background: Infertility is a public health issue in worldwide and in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. However, there is a lack of national population-based statistics in Saudi Arabia. The aim of this study was to provide the proportion of abnormal semen characteristics as the clinical diagnosis for male infertility amongst Saudi infertile couples. Methods: This was a retrospective study on infertile couples carried out in the Assisted Reproductive Technology unit at the International Medical Centre in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia between 2008 and 2014. A total of 2317 infertile couples were included in the study. Male infertility is diagnosed in the laboratory according to the criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO) for semen analysis. Results: Male infertility (as manifested by abnormal semen analysis) was found in 1521 (65.6%) couples and female infertility was found in 210 (9%) couples (p<0.01). One hundred and forty-two (6%) couples had a combination of both male and female infertility, while the cause of infertility in the remaining 444 (19%) couples was unexplained. Our results reveal that the contribution of abnormal semen characteristics to infertility is high comparing to other infertility causes.

Keywords: Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART), Female infertility, Infertile couples, Male infertility, Semen analysis

Cite this paper: Wardah Alasmari , Fawaz Edris , Zainab Albar , Abdulrahim Gari , Mamdoh Eskandar , Mohammed Al Fageah , Shamsuldin Zawawi , High Proportion of Abnormal Semen Characteristics among Saudi Infertile Couples, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2018, pp. 14-20. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20180801.03.

1. Introduction

- Infertility is defined as the failure of a couple to conceive following 12 months of unprotected sexual intercourse [1]. This is a significant global health problem that affects approximately 15% of couples throughout the world, with 56% of these couples seeking medical help [2-5]. Male infertility accounts for approximately 40% of sub-fertility cases, while female infertility accounts for 40% of cases, and about 20% of sub-fertility cases are due to unexplained causes [6, 7]. The most commonly cited statistic regarding male infertility is reported by Sharlip et al. who state that 20–30% of infertility cases are due to solely male infertility, and pure female infertility accounts for 50% of cases. The remaining 20–30% of cases are due to a combination of both male and female infertility [4]. However, this study does not clearly reflect the prevalence of male infertility in the different geographic regions. It is well known that male infertility is diagnosed in laboratory through descriptive semen analyses (count, motility, and morphology), and the quality of semen reportedly varies from country to country, suggesting the role of the geographic factors in male infertility. The differences in the quality of semen may imply the variation in the proportion of male factor infertility among subfertility cases throughout the world, which indicates a need for population-based studies. For example, Jungwirth et al. found that 15% of European couples are infertile and 7.5% of these cases are due to male infertility, which is similar to the United States [8]. A study on 1686 French infertile couples found that pure male factor infertility was implicated in only 20% of infertility cases, while 34% of infertility cases were due to female infertility and 38% were combined male and female infertility [9]. In Australia, the proportion of male infertility is similar to the United States and North America, which comprises approximately 40% of infertility cases [10, 11]. In Africa, male infertility represents up to 43% of cases, female infertility alone represents 25.8% of cases, while 20.7% of cases are due to a combination of both male and female infertility and the remaining 11.1% of cases are unexplained [12-14]. Therefore, the percentage of male infertility is noticeably different between different regions of the world [15]. Without accurate, region-specific data, it is not valid to statistically generalize the prevalence of male infertility worldwide. Many factors are associated with male infertility including urogenital tract infections, increased scrotal temperature, genetic abnormalities, and hormonal abnormalities [16].Although infertility is a public health issue in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [17] and elsewhere [5], with an increase in the use of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) procedures in recent years [18], there is a lack of national population-based statistics in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine the proportion of abnormal semen characteristics as the clinical diagnosis for male infertility amongst other causes of infertility in ART unit at the International Medical Centre in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

2. Patients and Methods

- This is a retrospective chart review of all ART procedures; intrauterine insemination (IUI), in vitro fertilization (IVF), intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) performed in the ART unit at the International Medical Centre between 2008 and 2014. The proportion of abnormal semen analysis among sub-fertile couples who underwent any of these procedures are examined for the whole period and each year. Approval for the study was obtained from the research and ethical committee of the International Medical Centre in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (IMC-IRB#: 2015-01-037- Appendix).The medical record numbers of patients who attended the infertility clinic and who underwent full assessments were identified by the hospital system. The patients’ data including history, female age, body mass index (BMI), antral follicle counts (AFC), and laboratory results, such as the assessment of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and the details of the husband’s semen analysis such as sperm count, motility and morphology were collected from their files.The seminal fluid analysis was measured according to the criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO) for semen analysis [19]. The diagnosis of abnormal semen was made when sperm concentration <15 Million /ml (oligozoospermia), total motility <40% (asthenozoospermia), sperm morphology <4% (teratozoospermia) and semen volume <1.5 ml [19]. To eliminate inter ejaculate variation, at least two separate samples were assessed before the diagnosis of abnormal semen analysis was made. The data of semen analysis on the same day of ART treatments were chosen to be recorded in the excel sheet form created for the study. Additionally, the proportion of sub-classifications of male infertility and female infertility is examined.The data were entered into a database and analyzed using Sigmaplot version 13. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

- This is a retrospective study from one center, conducted over seven years (2008–2014), analyzing data from 2317 couples who consulted clinicians for primary or secondary infertility. All the couples were evaluated thoroughly in our clinic for the cause of infertility. Demographic characteristics and semen analysis of sub-fertile participants undergoing ART based on their infertility diagnosis are represented in Table 1. Sperm count, motility, and morphology in male infertility group were significantly lower than other infertility groups (P<0.01). Female ages were significantly higher in female infertility groups, compared with other groups (P<0.01), as advanced maternal age could be one of the causes of subfertility in this group. FSH was significantly higher in female infertility groups than other groups, while AFC was significantly lower in female infertility groups compared with the others (P<0.01). There was no significant difference in BMI between groups.

| Figure 1. Proportion of sub-fertile couples according to the cause of infertility |

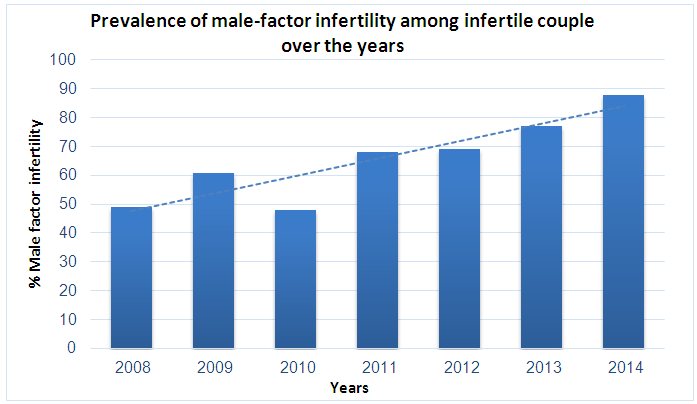

| Figure 2. Incidents of male infertility among sub-fertile couples from 2008–2014 |

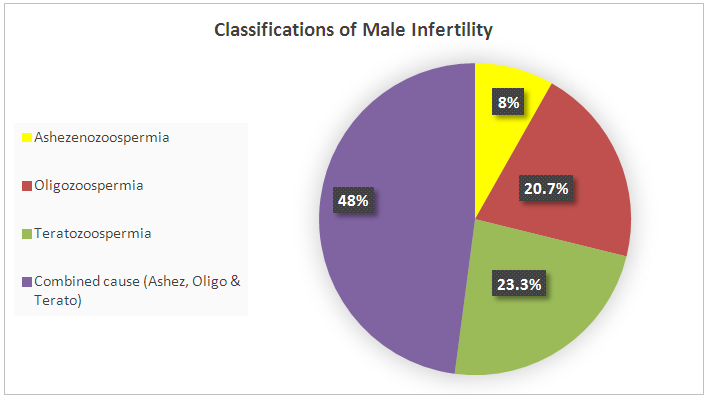

| Figure 3. Classifications of male infertility according to semen analyses |

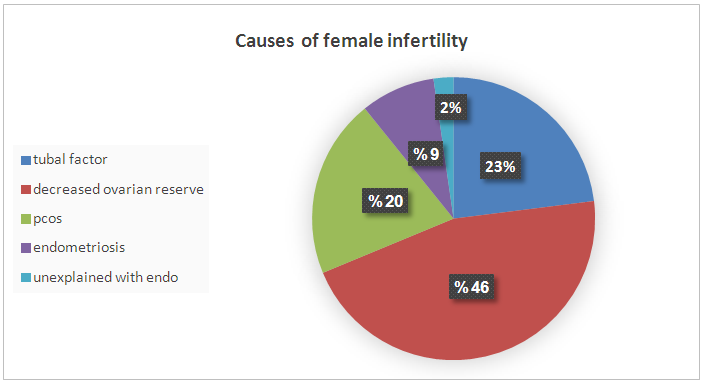

| Figure 4. Causes of female infertility |

4. Discussion

- This study aimed to examine the prevalence of male infertility amongst infertile couples attending the ART unit at the International Medical Centre in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Our data showed that abnormal semen cases were the most common cause of infertility (71.6%). According to the semen analyses, the most common type of abnormal semen cases was oligozoospermia (in isolation) and 48% were oligo-terato-asthenozoospermia in combination. However, decreased ovarian reserves and ovulation disorders were the most common causes of female infertility.The strength of this analysis is that it employed a large sample size (2317 sub-fertile couples). Furthermore, we document the prevalence of abnormal semen cases as laboratory diagnosis for male infertility (and their classifications) among the infertile couples at one of the biggest health centers in western Saudi Arabia that receive infertile couples from across the country. We believe that this will motivate other infertility centers to perform epidemiological studies on a national level which could help the future interventions in patient care and potential treatments. However, this study has certain limitations, including the retrospective nature of the analysis and the fact that we did not look at the underlying causes of infertility.As stated previously, statistics on the prevalence of male infertility are different in various regions. However, most studies show that male infertility represents approximately 40% of infertility cases (sometimes less at 20–30%). Meanwhile, female infertility accounts for 40–50% of all cases and about 20% of sub-fertility cases are due to unexplained causes [4, 6, 7, 9-11]. However, our data showed that male infertility was more common among infertile couples than female infertility, as pure male infertility accounted for 66% of cases. Only 9% of infertility was due to female infertility alone and 6% was due to a combination of both male and female infertility. The remaining 11% of sub-fertility cases was attributed to unexplained causes. Our findings are in agreement with other studies regarding male infertility in Saudi Arabia, which stated the greater contribution of male factors to infertility [20, 21]. The higher rate of abnormal semen cases as the most common cause of infertility among infertile couples was unclear, but there are several possible explanations. First, 75% of sub-fertile men in Saudi Arabia are heavy smokers, and approximately half of these patients smoke more than three packages of cigarettes per day [22]. A retrospective study to evaluate semen characteristics of Saudi infertile men showed that smoking and the presence of varicocele negatively affect semen parameters [20]. A plethora of studies show that paternal cigarette smoking is related to poor sperm quality and quantity and has the ability to damage spermatid DNA [23-26]. Second, the climate in Saudi Arabia is hot throughout most of the year, which may raise the intra-scrotal temperature and lead to sperm DNA damage, impairment of sperm quality and sperm production. The high contribution of male factors to infertility in our study (71.6%) is similar to studies from Africa where male infertility is as high as 63.7%. This may be also related to the hot weather in Africa [13]. Histopathological examination of testicular biopsies taken from Saudi infertile men showed that hypospermatogenesis is the commonest pattern in testicular biopsies [27]. Another study evaluated pathological changes in testicular biopsies taken from males with infertility in Saudi Arabia found a higher percentage of germinal cell aplasia [28].Approximately 48% of samples with semen abnormalities experienced oligo-terato-asthenozoospermia in combination, while another half (52%) had single factor abnormality. Oligozoospermia (20.7%) and teratozoospermia (23.3%) were the most common type of abnormal semen cases according to the semen analyses, which is clearly shown in Table 1 as the mean and median of abnormal sperm morphology were approximately 3%. Asthenozoospermia in isolation accounted only for 8% of male infertility cases. Our findings are in agreement with the study by Alenezi et al (2014) on Saudi infertile men in Riyadh, which have demonstrated that half of semen samples had single factor abnormality and the majority being teratozoospermia [20]. In contrast to our findings, other studies have reported that asthenozoospermia is more common among subfertile men [13, 29, 30]. Regarding causes of female infertility, decreased ovarian reserves and ovulation disorders were the most common aetiological factors responsible for female infertility. This is clear in Table 1, as FSH were significantly higher in female infertility groups, while AFC was significantly lower in female infertility groups compared with the others, suggesting poor ovarian reserve is one of the causes of infertility in this group. In contrast to our observations, other studies have reported that tubal occlusion was the most common cause of female infertility (African study. The differences in findings between studies are possibly related to several factors including environmental effects, design of the studies and inclusion criteria.Many studies suggest that the quality of semen is declining across the world. A meta-analysis of 61 articles published by Carlson et al. (1992) demonstrates a clear reduction in sperm counts from 113x106 to 66x106 and semen volume from 3.4 to 2.75 ml between 1940 and 1990 [31]. These findings have been confirmed by subsequent studies in the United Kingdom [32, 33] France [34], New Zealand [35] and Finland [36]. These studies come to a similar conclusion that semen parameters have declined. The deterioration in semen quality can be explained by the increase in the incidence of testicular cancer, as well as lifestyle factors, such as smoking, alcohol, drug use and obesity [31, 33, 34, 36]. On the other hand, a recent study in Sweden reported no decline in sperm counts over the last 10 years [37]. Although some studies report declines in sperm count and motility, there is no direct evidence of declining male fertility. However, there was an increase in the use of ART during the time that these studies were conducted. This study looked at all ART procedures (IUI, IVF, and ICSI) performed in our center between 2008 and 2014 and examined the proportion of abnormal semen cases among sub-fertile couples that underwent ART procedures in a year. The data showed that the incidence of male infertility (as manifested by abnormal semen analysis) increased from 2008–2014. We do not know the reason for this increase, but it is possible that the majority of sub-fertile men are becoming more open about their infertility problems and seeking medical treatment.

5. Conclusions

- Our findings demonstrate a significant number of infertility cases in Saudi Arabia were due to the male factor. Thus, more attention should be paid to the husband for any intervention aim at prevention of infertility. Further studies are required to identify the factors causing this phenomenon of a high proportion of abnormal semen cases among Saudi infertile couples, which could improve future interventions in patients' care and treatments.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML