-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics

p-ISSN: 2163-1433 e-ISSN: 2163-1441

2017; 7(4): 101-105

doi:10.5923/j.cmd.20170704.03

Modified Negative Marking Schemes in Multiple Choice Questions in a Health Institution in Nigeria

Ernest Ndukaife Anyabolu1, 2, Innocent Chukwuemeka Okoye1

1Department of Medicine, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Awka, Nigeria

2Department of Medicine, Imo State University, Orlu, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ernest Ndukaife Anyabolu, Department of Medicine, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Awka, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background and Objectives: The use of multiple choice questions (MCQs) is an objective method of assessment of knowledge. The true/false pattern of MCQs is often applied in medical schools. Negative marking for the true/false MCQs may influence the overall reliability, validity, and outcome of the assessment. This study was set out to evaluate aspects of negative marking schemes in MCQs in a medical school in Nigeria. Methodology: This was a cross sectional study involving a set of final year medical students. Multiple choice questions comprising of 100 true/false questions and 70 best of five (BOF) options were administered in 2 sessions, 7 days apart, and 3 marking schemes were used. Scheme A: “Informed negative marking but no negative marking” Scheme B: “Informed no negative marking and no negative marking”. Scheme C: “Informed negative marking and negative marking”. Number right scheme was used for the BOF. The results were compared between the 3 marking schemes. Results: The students’ mean score 46.1% for Scheme A was higher than 39.9% for Scheme C (p<0.001), but lower than 57.7% for Scheme B, (p=0.028). The differences in the positive scores, as well as the negative scores between the three schemes were not significant. (df 22, p=0.288) (df=20, p=0.862) There was a near perfect correlation between the mean score for Scheme A and that for Scheme C (r=0.97 p<0.001). However, there was a moderate correlation between the mean score for Scheme A and Scheme B. The mean score for Scheme C was a predictor of the mean score for Scheme A. Conclusion: The Marking Schemes for MCQs “Informed negative marking but no implementation of negative marking” and “Informed negative marking and implementation of negative marking” were closely related, and were more reliable and valid than the Marking Scheme “Informed no negative marking and no implementation of negative marking” for the true/false MCQs. Negative marking should be adopted in true/false options in MCQs in medical schools.

Keywords: Multiple choice questions, Negative marking schemes, True or false questions, Informed negative marking, Informed no negative marking, Nigeria

Cite this paper: Ernest Ndukaife Anyabolu, Innocent Chukwuemeka Okoye, Modified Negative Marking Schemes in Multiple Choice Questions in a Health Institution in Nigeria, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 101-105. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20170704.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The use of multiple choice questions (MCQs) for the assessment of knowledge is common in higher institutions [1]. The essay forms of written examinations seem to be giving way for MCQs; some centers still use a combination of MCQs and essays [2]. Unlike essay forms, MCQs have been shown to be more objective in assessing written knowledge [3].Studies have shown that MCQs could adopt negative or non-negative marking schemes [4, 5]. In a negative marking scheme, wrong answers are penalized with negative marks, unanswered questions zero, whereas in non-negative marking wrong answers and unanswered questions are given no marks, that is, zero [6]. Guessing by students in MCQs may reduce the reliability of the tests [6, 7]. However, studies have demonstrated that guessing tends to decline with heavier penalties when the negative marking is prominent, and increases with little penalties in negative marking and non-negative marking [6, 8, 9]. The concept of fair penalty in a negative marking scheme to discourage distracter has been put at less than one where the mark allotted to a stem is 1 [6, 9].The reliability, validity and objectivity of MCQs tend to increase as the number of questions increases [6, 10, 11]. The tests efficiency might be influenced by the variability in the number of stems in each question as well as the marking scheme [6, 11, 12].There is a paucity of studies on MCQs marking schemes in higher institutions in Nigeria. This has prompted us to undertake this study to evaluate negative marking schemes in MCQs in the assessment of knowledge in a higher institution in Nigeria.

2. Materials and Methods

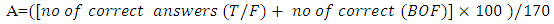

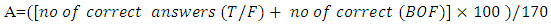

- This was a cross-sectional study involving 34 final year medical students preparing for their final MBBS examinations. It was conducted in the Department of Medicine, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Nigeria, in June and July 2017. Multiple choice questions (MCQs) comprising of 100 true/false questions and 70 best of five (BOF) options were administered in 2 sessions, 7 days apart. For the BOF questions Number Right (NR) was used in which +1 mark was awarded for a correct answer, no mark for unanswered question or wrong answer. For the 100T/F questions, the answers were scored using 3 different marking schemes. Scheme AMCQs 100T/F. ‘Informed negative marking but no negative marking’The instructions for the examination were as followsMCQs 5th MBBS Mock Examination Date: 29th June, 2017.Time Allowed: 1hour 15minutesSECTION A: Numbers 1 – 20. Each question has 5 stems. Indicate whether each stem is true or false. Each correctly answered stem carries +1 mark, each wrongly answered stem carries -1 mark while each unanswered stem does not carry any mark. SECTION B: Numbers 21 – 90. Each question has 5 stems. For each question choose the most appropriate answer; only one answer is correct. Marking more than 1 stem invalidates the answer.In this session, the assessment was conducted as part of 5th MBBS Mock Examination. SECTION A contained 20 questions, and each has 5 stems, bringing the total number to 100 T/F questions and 70 BOF questions. For the 100 T/F questions, the candidates were informed there would be negative marking at the time of taking the examination. However, in the marking, no negative marking was implemented. The overall scores were determined as

Scheme BMCQs 100T/F. “Informed no negative marking and no negative marking”.The candidates were given another assessment 7 days later designed to serve as part of a Continuous Assessment that would be used as a part of the 5th MBBS Main Examination. However, the same questions were administered to them.MCQs 5th MBBS Quiz Date: 6th July, 2017.Time Allowed: 1hour 15minutesSECTION A: Numbers 1 – 20. Each question has 5 stems. Indicate whether each stem is true or false. Each correctly answered stem carries +1mark, each wrongly answered stem carries no mark; similarly, each unanswered stem does not carry any mark. SECTION B: Numbers 21 – 90. Each question has 5 stems. For each question choose the most appropriate answer; only one answer is correct. Marking more than 1 stem invalidates the answer.For the 100 T/F questions, the candidates were informed there would be no negative marking at the time of taking the examination. In the marking, no negative marking was implemented. The overall scores were determined as

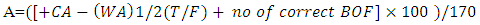

Scheme BMCQs 100T/F. “Informed no negative marking and no negative marking”.The candidates were given another assessment 7 days later designed to serve as part of a Continuous Assessment that would be used as a part of the 5th MBBS Main Examination. However, the same questions were administered to them.MCQs 5th MBBS Quiz Date: 6th July, 2017.Time Allowed: 1hour 15minutesSECTION A: Numbers 1 – 20. Each question has 5 stems. Indicate whether each stem is true or false. Each correctly answered stem carries +1mark, each wrongly answered stem carries no mark; similarly, each unanswered stem does not carry any mark. SECTION B: Numbers 21 – 90. Each question has 5 stems. For each question choose the most appropriate answer; only one answer is correct. Marking more than 1 stem invalidates the answer.For the 100 T/F questions, the candidates were informed there would be no negative marking at the time of taking the examination. In the marking, no negative marking was implemented. The overall scores were determined as Scheme CMCQs 100T/F. Informed negative marking and negative marking.This was the same examination as Session A. The candidates were informed there would be negative marking and negative marking, taken as +1 mark for each correct answer and -1/2 mark for each wrong answer, was implemented in the marking.The overall scores were determined as

Scheme CMCQs 100T/F. Informed negative marking and negative marking.This was the same examination as Session A. The candidates were informed there would be negative marking and negative marking, taken as +1 mark for each correct answer and -1/2 mark for each wrong answer, was implemented in the marking.The overall scores were determined as CA=correct answers T/FWA=wrong answers T/FThe mean values of the scores, Positive scores and negative scores for the 3 Sessions (A, B and C) were obtained and the results compared between the groups.Data AnalysesThe data were analyzed using the SPSS version 21. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the mean, range, median, variance and percentile of the students’ scores, the positive scores (correct answers) and negative scores (wrong answers) and the overall scores (mean scores). The mean values of the scores for the 3 marking schemes were compared using ANOVA. Post hoc analysis was done using Turkey/LSD. Continuous variables were compared between the groups using student t-test. Correlation statistics were used to determine the association between the marking schemes mean scores, while bivariate linear regression analysis was used to determine the strength of the mean scores for Schemes B and C to predict the mean score for Scheme A. All tests were two-tailed. P<0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

CA=correct answers T/FWA=wrong answers T/FThe mean values of the scores, Positive scores and negative scores for the 3 Sessions (A, B and C) were obtained and the results compared between the groups.Data AnalysesThe data were analyzed using the SPSS version 21. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the mean, range, median, variance and percentile of the students’ scores, the positive scores (correct answers) and negative scores (wrong answers) and the overall scores (mean scores). The mean values of the scores for the 3 marking schemes were compared using ANOVA. Post hoc analysis was done using Turkey/LSD. Continuous variables were compared between the groups using student t-test. Correlation statistics were used to determine the association between the marking schemes mean scores, while bivariate linear regression analysis was used to determine the strength of the mean scores for Schemes B and C to predict the mean score for Scheme A. All tests were two-tailed. P<0.05 was taken as statistically significant. 3. Results

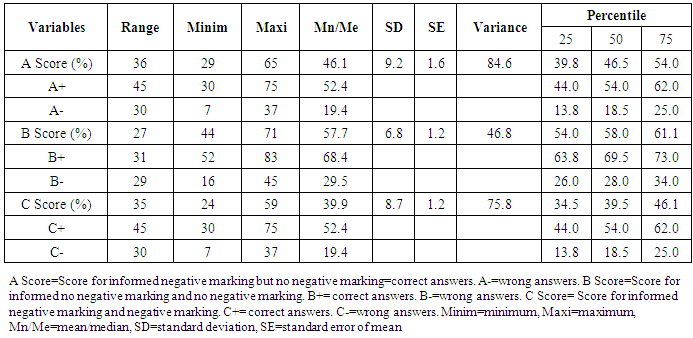

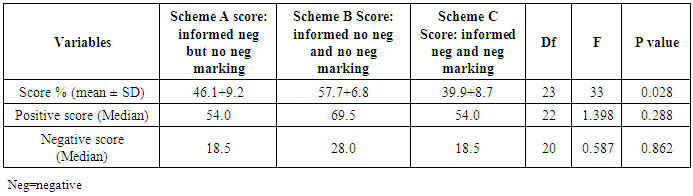

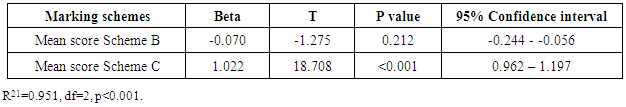

- This study evaluated the effects of negative marking in multiple choice questions in the assessment of knowledge in a set of medical students.The students’ mean scores were 46.1% for Scheme A, 57.7% for Scheme B and 39.9% for Scheme C (Table 1). The variance and percentile values are shown in Table 1. These 3 mean score values observed among the 3 marking schemes differed significantly (Table 2). The mean score 46.1% for Scheme A was significantly higher than the mean score 39.9% for Scheme C (p<0.001); it was however, significantly lower than the mean score 57.7% for Scheme B, p=0.028.The positive scores from correctly answered questions showed no significant difference between the 3 marking schemes, (df=22, p=0.288). Similar results were obtained for the negatives scores across the 3 different schemes, (df=20, p=0.862) (Table 3).The mean score for Scheme A showed a near perfect correlation with the mean score for Scheme C, (r=0.97, p<0.001), as well as a moderate correlation with the mean score for Scheme C (Table 3).Multivariate linear regression analysis showed that the mean score for Scheme C predicted the mean score for Scheme A, (p<0.001) while the mean score for Scheme C did not predict it (Table 4).

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The students’ mean score 46.1% in Scheme A MCQs Informed negative marking but no negative marking was significantly higher than their mean score 39.9% for Scheme C when there was Informed negative marking and negative marking. The observed difference in the students’ mean scores between the 2 marking schemes could be explained by the actual execution of negative marking in Scheme C but not in Scheme A. This agrees with earlier studies which also showed that scores obtained by students when negative marking is adopted are usually lower than those recorded when non-negative, number right (NR) marking scheme is used [6, 13], but increase when partial knowledge is rewarded [13]. This observed difference might be explained, in part, by the fact that negative marking imposes heavier penalties for wrong answers compared to non-negative, number right schemes [6]. Furthermore, partial knowledge, assessed by a partial-credit marking scheme, in a non-negative, number right setting, tests the ability of students to discriminate between absence of knowledge and full knowledge, compared to the negative marking scheme which assesses students’ ability to discriminate between absence of knowledge, misinformation and full knowledge [6, 13]. In contrast, however, some studies demonstrated no marked difference in student performance in MCQs between these two marking schemes [14, 15]. It was demonstrated in this study that the students’ mean score 46.1% in Scheme A Informed negative marking but no negative marking was significantly lower than their mean score 57.7% when Scheme B Informed no negative marking and no negative marking was adopted. Specific instructions to students about marking schemes in MCQs are necessary and would influence their behavior and performance [16-18]. With clear instruction that wrong answers would attract penalties, the tendency to guess would decline [18], explaining the students’ low mean score in Scheme A compared to their performance in Scheme B. Expectedly in this study Scheme A has a near perfect correlation with, and also predicted, Scheme C but did not predict Scheme B. Negative marking, as one study showed, does not address the issue of variation in risk taking behavior of students in guessing [19]. Students with equal academic ability may have different scores, as those with high risk taking tendency would be more likely to guess and to score more marks [20]. In contrast, a study has documented that guessing does not increase scores of students [16], contrary to the observation in Scheme B, in our study, in which the absence of elements of penalty perhaps, made the students mean scores to be high, obviously with instruments of guessing from the students. A fair negative marking should employ a penalty for a wrong answer and still address the issue of guessing to be able to improve on the reliability and validity of the test method [6, 21]. In this study, -1/2 mark was adopted for each wrong answer in Scheme C, differing from those that used -1 mark [22]. The performance of a negative marking scheme which considers the elimination of guessing is dependent on the number of stems in each question; the tendency to eliminate guessing increases as the number of stems increases [5, 10, 14, 22]. A 5-stem true/false MCQ logically has 2 stems each, like ours in this study. The negative marking Scheme C in this study is fair. Outright utility of a stiffer penalty of -1 mark for a wrong answer would be of immense importance in conditions where accuracy is needed to avert dire consequences as in the medical sciences and core engineering [23, 24]. Nonetheless, Scheme C would be a fair negative marking scheme in undergraduate medicine examinations [8].Overall, this study has demonstrated that fair negative marking schemes adopting a penalty of -1.2 mark for a wrong answer in a structure of true/false is reliable and valid compared to a similar structure without instruction for negative marking and without implementation of negative marking. It further demonstrated a variance 84.6 and 75.8 respectively between Scheme A and Scheme C. Scheme A might be used when the scores are low and Scheme C when they are high [25].

5. Conclusions

- Marking Schemes for MCQs “Informed negative marking but no implementation of negative marking” and “Informed negative marking and implementation of negative marking” were closely related, and were more reliable, valid negative marking schemes than Marking Scheme “Informed no negative marking and no implementation of negative marking” for the true/false MCQs. Negative marking should be adopted for the true/false options in MCQs for a more objective, reliable and valid assessment of knowledge in medical schools.

Limitations of the Study

- The effects of +1 mark for a correct answer and -1 mark for a wrong answer were not explored in this study. The best cut-off scores were also not evaluated. These would have helped in further analyzing the effects of the marking schemes examined in this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML