Mohammad I. Fatani1, Taha H. Habibullah2, Khalid A. Alfif3, Abdulrahman I. Ibrahim4, Badr Althebyani5

1Dermatology Consultant, Hera Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

2Dermatology Specialist, National Guard Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

3Consultant dermatologist, Hera General Hospital, Makkah, KSA

4Dermatology Intern, Hera General Hospital, Makkah, KSA

5Hera General Hospital, Radiology Department, Hera General Hospital, Makkah, KSA

Correspondence to: Mohammad I. Fatani, Dermatology Consultant, Hera Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Background: Psoriasis is a common chronic dermatological disease that has a negative impact on the psychological status and the social interaction of the patient and their overall quality of life (QoL). Objectives: The aim of this study was to assess the QoL of patients with psoriasis in Makkah using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and to evaluate the correlation between the DLQI and clinical severity of psoriasis. Materials and Methods: This observational, cross-sectional study took place over a three-month period, from January to March 2015, at Hera General Hospital in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. All patients with psoriasis attending the dermatology clinic during this period were included in the study. Results: A total of 79 patients who attended Hera general hospital were enrolled in the study, with male patients representing 48.1% of the psoriatic patients and female patients representing 51.9% (sex ratio 1:1.1). The mean age is 35.27 and the mean psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) was 10.67. Onset occurred before 40 years of age in the majority of patients (60.8%), 27.3% had positive family history, and 73.2% had associated comorbidities. The mean DLQI score in all patients was 10.67 ± 5.54. Conclusions: The present data suggest that age, gender, and clinical severity are associated with the QoL of patients with psoriasis. The observations reported here provide significant new insights into factors affecting the life quality of patients with psoriasis in Makkah, but the study was limited in several ways that might be addressed in further research.

Keywords:

Psoriasis, DLQI, PASI, Makkah, Saudi

Cite this paper: Mohammad I. Fatani, Taha H. Habibullah, Khalid A. Alfif, Abdulrahman I. Ibrahim, Badr Althebyani, Impact of Psoriasis on Quality of Life at Hera General Hospital in Makkah, Saudi Arabia, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 7-12. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20160601.02.

1. Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic immunologic disease characterized by red papules and plaques with a silver-colored scale [1] that affects about 0.6%–4.8% of the global population. Although psoriasis usually is not a life threatening condition (with the exception of cardiovascular and psychiatric comorbidities) and can be treated in an outpatient setting, it is a challenging and frustrating condition for patients and often for their physicians as well.A diagnosis of psoriasis is informed by an examination of the skin. The classic symptoms of Psoriasis Vulgaris are highly visible chronic erythematous plaques covered with silvery-white scales on the elbows, knees, scalp, umbilicus, and lumbar area [2].Treatments are chronic and sometimes complicated, but are commonly divided into three main types: topical treatments, light therapy, and systemic medications. Treatment planning is further complicated by the need to take into consideration patients’ individual preferences, expectations, and quality of life (QoL). Besides the complexity of treatment, there are some other management challenges in the treatment of psoriasis such as poor adherence to treatment, the risk of comorbidities, childhood psoriasis, and lifestyle modification and maintenance [3].There are many different tools to evaluate the severity of psoriasis including the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), physician global assessment (PGA), and QoL. The concept of the latter has been divided into several components, including psychological, social, and physical domains [4], all of which have been well documented [5]. The severity of psoriasis closely correlates with the severity of depression and, in turn, with the frequency of suicidal ideation [6, 7].However, disease severity, as measured by instruments such as the PASI, is not the sole factor that determines the burden of illness because relatively minor psoriasis located on visible parts of the body may also have a detrimental effect on health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) [8].Simple QoL measures are often used by psoriatic patients who wish to express their feelings, and the measurement of the severity of psoriasis is based on the signs and symptoms of the disease [9]. One of the tools used in psoriasis to measure the QoL is the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), a reliable and validated 10-item questionnaire covering six dimensions [6]. Each question has four different answers that correspond to a score of 0 (not at all), 1 (a little), 2 (a lot), and 3 (very much).The six domains of the DLQI cover symptoms and feelings (questions 1 and 2), daily activities (questions 3 and 4), leisure (questions 5 and 6), work/school (question 7), personal relationships (questions 8 and 9), and treatment (question 10). The maximum score is 30 and the minimum is 0. The higher the score, the more the QoL is impaired. A DLQI score of 0-1 is interpreted as no effect at all on the patient’s life, 2-5 as a small effect, 6-10 as a moderate effect, 11-20 as a very large effect, and 21-30 as an extremely large effect. The reliability and validity of the Persian version of the DLQI have been confirmed previously in patients with vitiligo [6].

2. Purpose of the Study

The objective of this study is to assess the QoL of patients with psoriasis in Makkah using the DLQI and to evaluate the correlation between the DLQI and clinical severity of psoriasis.

3. Methods and Materials

Data were collected between January 1st and March 30th, 2015, after enrolling patients with Psoriasis Vulgaris attending the Dermatology Clinic at Hera General Hospital in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Data collection was conducted via the dermatologists. The Arabic version of the DLQI questionnaire was administered to the patients, and an assessment of the disease was carried out using the PASI and PGA. Patient data were documented on a special form, including gender, age, BMI, smoking status, and detailed information about the type of treatment, including dose, frequency, and duration.Data were entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences IBM SPSS-14.0. All quantitative variables were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

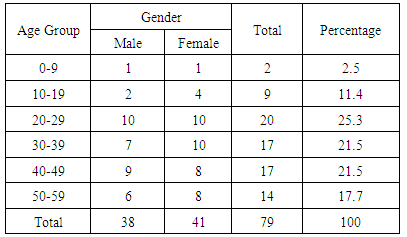

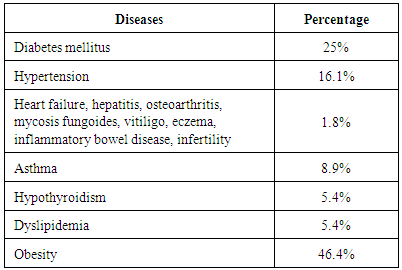

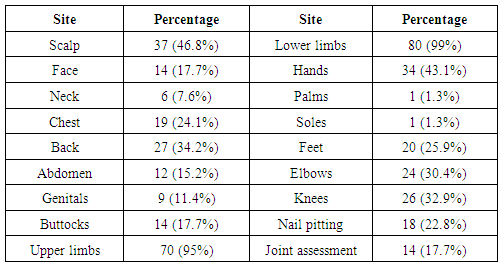

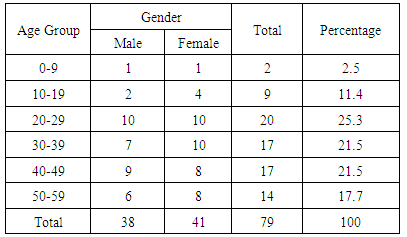

A total of 79 patients were enrolled in the study, all of whom attended Hera General Hospital in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. All patients completed the DLQI questionnaire. Male patients represented 48.1% and female patients represented 51.9% of the psoriatic patients (sex ratio 1:1.1).Table 1 demonstrates the age group in relation to gender. The mean age of our patients is 35.27 (SD=13.16). The mean PASI was 10.67 (SD=5.54) with a range of 0 to 24. Most of our patients’ (60.8%) psoriasis occurred before 40 years of age with a mean age at onset of 35 (SD=13.16) years, and the median is also 35 (minimum = 6, maximum = 56). Among psoriatic patients, we found that 27.3% have positive family history and 73.2% have associated comorbidities as seen in Table 2. The site involvement is shown in Table 3.Table 1. Age group in relation to gender

|

| |

|

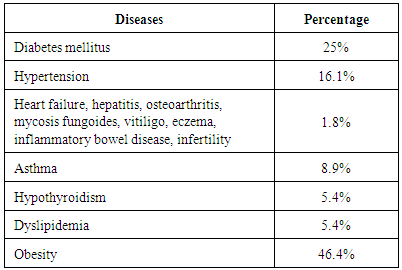

Table 2. List of co-morbidities among psoriatic patients

|

| |

|

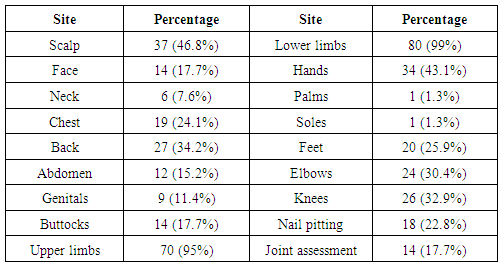

Table 3. Detail of site involvement for our patients

|

| |

|

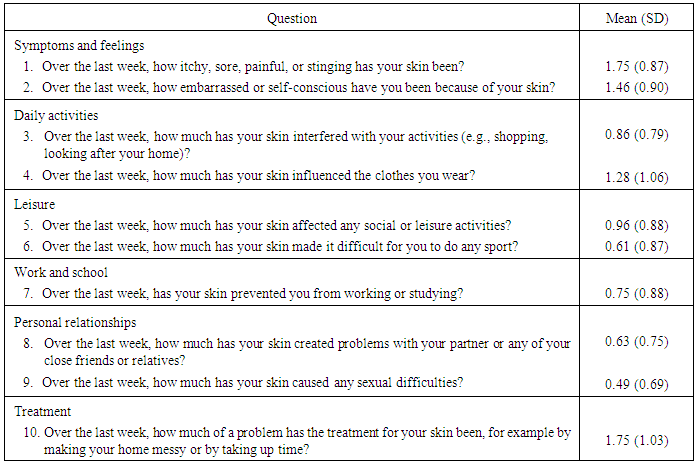

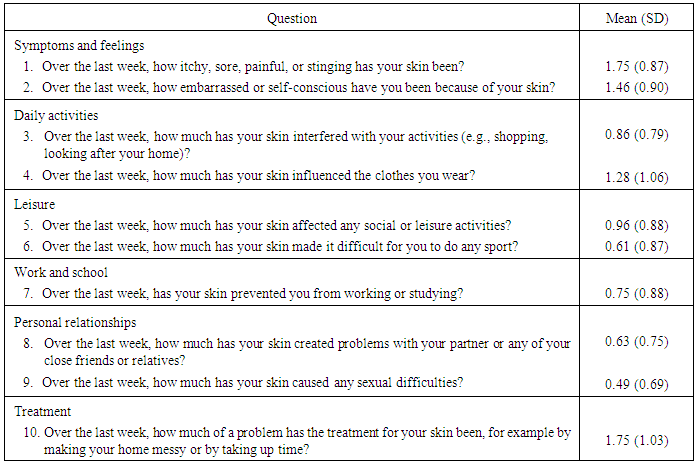

The HR-QoL was assessed with the DLQI questionnaire, and the detailed DLQI scores are summarized in Table 4. A total of 5, 12, 19, 41, and 2 of the 79 patients scored 0-1, 2-5, 6-10, 11-20, and 21-30, respectively, which indicates that 6.3%, 15.2%, 24.1%, 51.9%, and 2.5% of all patients report that psoriasis has "no effect at all," a "small effect," a "moderate effect," a "very large effect," or an "extremely large effect" on their life, respectively. The section for symptoms and feelings had the highest score while the section for personal relationships (sexual difficulty) had the lowest score. Tables 5 and 6 demonstrate the relation between age group and patient gender to the DLQI severity for psoriatic patients.Table 4. DLQI scores of patients with psoriasis (n = 79)

|

| |

|

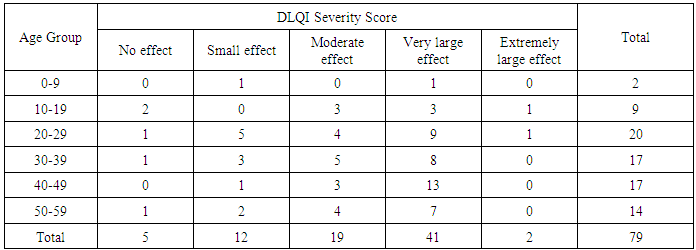

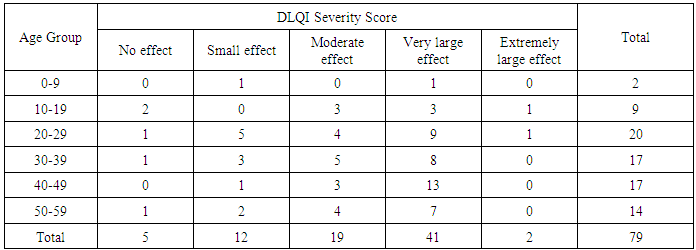

Table 5. Age group related to DLQI score for psoriasis patients

|

| |

|

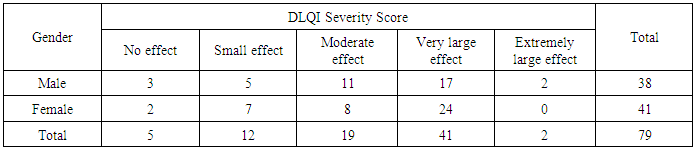

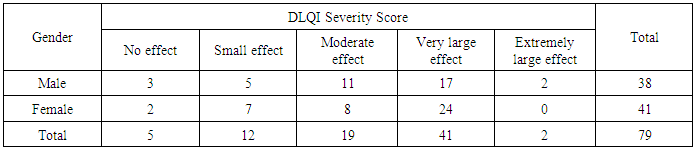

Table 6. Gender of our psoriatic patients in relation to DLQI score

|

| |

|

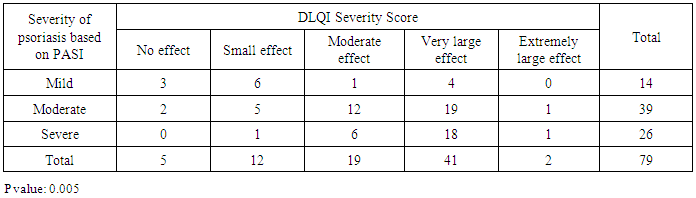

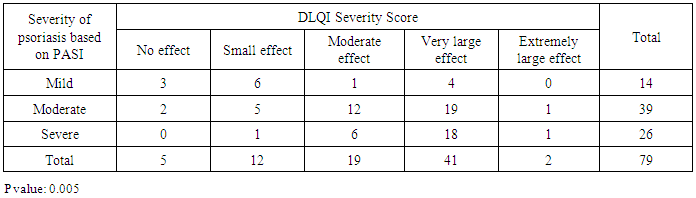

The correlation between DLQI and clinical severity scores based on the PASI and PGA scores are shown in Tables 7 and 8. The mean DLQI score in all patients was 10.67 ± 5.54, with a range from 0 to 24. The mean PASI score in all patients was 14.67 ± 10.15, with a range from 0 to 46. Table 9 shows the correlation between psoriasis severity score and patient gender.Table 7. Severity of psoriasis based on PASI in relation to DLQI severity score

|

| |

|

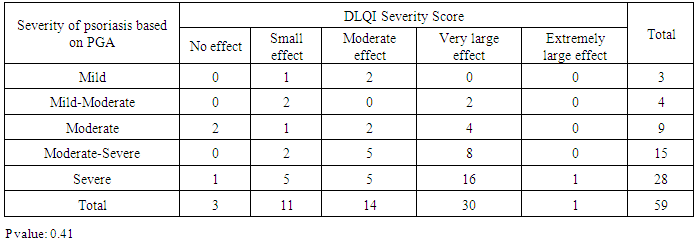

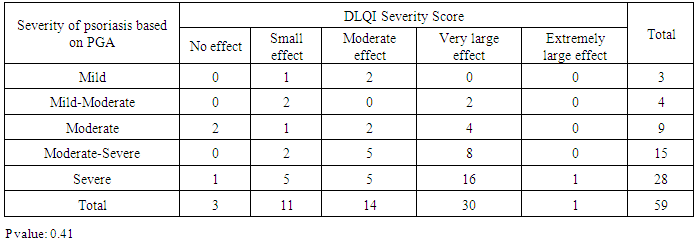

Table 8. Severity of psoriasis based on PGA in relation to DLQI severity score

|

| |

|

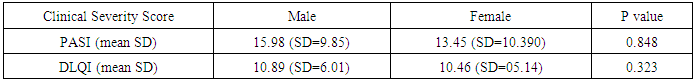

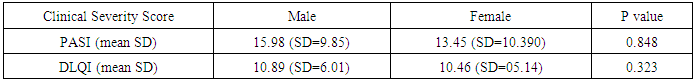

Table 9. Correlation between psoriasis severity score and patient gender

|

| |

|

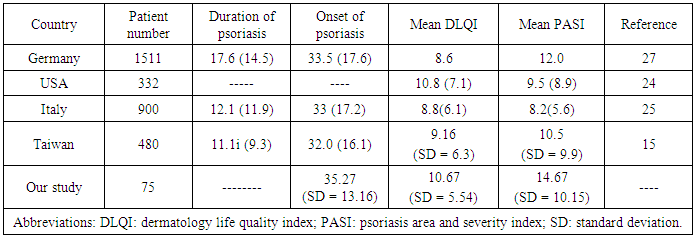

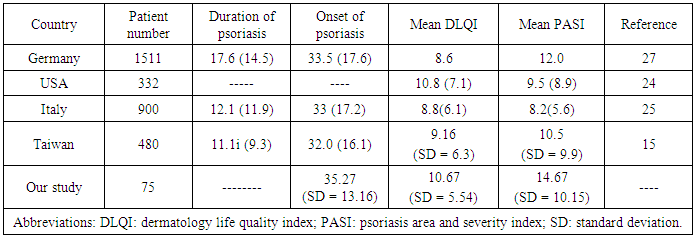

Table 10. Cross-sectional studies of DLQI and PASI in patients with psoriasis

|

| |

|

5. Discussion

Psoriasis is a distressing and recurrent disease that significantly impairs QoL and has no permanent cure. The QoL of psoriasis patients is reported to be lower than other diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cancer [8], and the QoL score for psychological factors is also lower in psoriasis patients [9, 10].Studies have shown that doctors and patients differ in their assessments of severity [11, 12] because doctors define the severity of psoriasis based on symptoms and area of skin lesions, while patients focus on impaired daily activities or QoL [11, 12]. As such, when assessing the severity of the disease it is important to assess not only the severity of the skin lesions but also patient QoL. In our study, we therefore use the DLQI as a tool to measure the QoL of our psoriatic patients. Psoriasis does not discriminate by gender [13], despite the fact that some reports have suggested that it is more prevalent in men than in women [14, 15]. The proportion of women was higher than that of men in our study (51.9.5% vs. 48.1%), which is comparable with another study [16]. This could be explained by the tendency in men to keep themselves removed from the social effects of psoriasis, while women, in contrast, are more likely to feel upset in social settings [17] and may be more likely to perceive a greater impact on mental QoL [18]. However, the gender factor was not associated with the DLQI score in our study, which was statistically insignificant (p = 0.393).Age is an important factor that affects the QoL in patients with psoriasis. A greater impact of psoriasis on physical health has been found in older patients, whilst a greater impact on psychosocial aspects has been found in younger ones [19-21].Interestingly, we observed that patients less than 40 years had higher DLQI scores in this study, which is comparable with other studies [14, 20]. However, another study from Italy showed that older patients with psoriasis have worse life quality [16]. This difference could be explained by the fact that the age factor in relation to the QoL of psoriasis patients may vary in different countries, and further research is necessary to explain this diversity.Our data show that the mean DLQI score was 10.67 (SD=5.54), and the mean PASI score was 14.67 (SD=10.15), roughly in line with previous cross-sectional studies (Table 10). In the DLQI questionnaire, our study showed higher scores for symptoms and feelings and lower scores for the sexual problems, which is in line with previous studies [22, 23].Interestingly, 82% of our patients had moderate to severe psoriasis according to the above definition of psoriasis severity [24, 25], and 78.5% reported that their condition had a moderate to extremely large effect on their life (DLQI > 6), which is statistically significant (p=0.005).The results of this study confirm that clinical severity is related to QoL in psoriasis patients, which is consistent with another study showing that DLQI scores have a positive correlation with PASI and PGA scores [26]. However, some studies reported weak correlations between clinical severity and QoL [23, 24]. This variation may have occurred because patients with a worse HR-QoL have greater dissatisfaction with their current treatment compared with those with a better HR-QoL [25].

6. Conclusions

The presented data suggest that age, gender, and clinical severity are associated with the QoL of patients with psoriasis. The observations reported here provide significant new insights into factors impacting the life quality of patients with psoriasis in Makkah that might be addressed in further research in the future.

References

| [1] | Feldman SR. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of psoriasis. In: Basow DS, editor. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc; 2011. |

| [2] | Schön MP, Boehncke WH. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1899-912. |

| [3] | Coates LC, Jonckheere CL, Molin S, Mease PJ, Ritchlin CT. Summary of the International Federation of Psoriasis Association’s (IFPA) Meeting: A report from the GRAPPA 2009 Annual Meeting. J Rheumatol. 2011; 38: 530–539. |

| [4] | Price P, Harding KG. Defining quality of life. J Wound Care 1993; 2: 304-6. |

| [5] | Augustin M, Zschocke I, Lange S, Seidenglanz K, Amon U. Quality of life in skin diseases: Methodological and practical comparison of different quality of life questionnaires in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Hautarzt 1999; 50: 715-22. |

| [6] | Akay A, Pekcanlar A, Bozdag KE, Altintas L, Karaman A. Assessment of depression in subjects with psoriasis vulgaris and lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2002: 16: 347-52. |

| [7] | Gupta MA, Shorck NJ, Gupta AK, Kirby S, Ellis CN. Suicidal ideation in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 1999: 23: 346-15. |

| [8] | Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum MI, Fleisher AB, Jr, Rebussin, Dm. Psoriasis cause as much disabilities as other major medical disease. J Am Acad Dermatolo 1999: 410-209. |

| [9] | Finlay AY, Cloles EC. The effect of severe psoriasis on the quality of life of 369 patients. Br J Dermatol 1995; 123: 236-244. |

| [10] | Nichol MB, Magolies JE, Lippa E, Rowe M, Quell J. The application of multiple quality of life instruments in individuals with mild to moderate psoriasis. Pharmacoeconomics 1996; 10: 611-653. |

| [11] | Finlay AY, Kelly SE. Pso-an index of disability. Clin-exp Dermatol 1987: 128-11. |

| [12] | Krueger GG, Feldman SR, Gamisa C, Duvis M, Elder JT. Consideration of patients with psoriasis and their clinicians. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000: 43: 281-285. |

| [13] | Raychaudhuri SP, Farber EM. The prevalence of psoriasis in the world. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001; 15: 16-7. |

| [14] | Lin T-Y, See LC, Shen Y-M, et al. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis in northern Taiwan. Gung Med J 2011; Vol (34) No. 2: 755-760. |

| [15] | Yip SY. The prevalence of psoriasis in the Mongoloid race. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984; 10: 965-8. |

| [16] | Sampogna F, Chren MM, Melchi CF, Pasquini P, Tabolli S, Abeni D. Age, gender, quality of life and psychological distress in patients hospitalized with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2006; 154: 325-31. |

| [17] | Perrott SB, Murray AH, Lowe J, Ruggiero KM. The personal-group discrimination discrepancy in persons living with psoriasis. Basic Appl Social Psychol 2000; 22: 57–67. |

| [18] | Misery L, Thomas L, Jullien D, et al. Comparative study of stress and quality of life in outpatients consulting for different dermatoses in 5 academic departments of dermatology. Eur J Dermatol 2008; 18: 412–415. |

| [19] | Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Menter A, Stern RS, Rolstad T. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: Results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 280-4. |

| [20] | Zachariae R, Zachariae H, Blomqvist K, Davidsson S, Molin L, Mørk C, Sigurgeirsson B. Quality of life in 6497 Nordic patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2002; 146: 1006-16. |

| [21] | Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Silverdahl M, Hermansson C, Lindberg M. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis measured with SF-36, DLQI and a subjective measure of disease activity. Acta Derm Venereol 2000; 80: 430-4. |

| [22] | Bhosle MJ, Kulkarni A, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006; 4: 35. |

| [23] | Mazzotti E, Barbaranelli C, Picardi A, Abeni D, Pasquini P. Psychometric properties of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) in 900 Italian patients with psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol 2005; 85: 409-13. |

| [24] | Feldman SR. A quantitative definition of severe psoriasis for use in clinical trials. J Dermatolog Treat 2004; 15: 27-9. |

| [25] | Schmitt J, Wozel G. The psoriasis area and severity index is the adequate criterion to define severity in chronic plaque-type psoriasis. Dermatology 2005; 210: 194-9. |

| [26] | Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994-2007: A comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 997-1035. |

| [27] | Augustin M, Krüger K, Radtke MA, Schwippl I, Reich K. Disease severity, quality of life and health care in plaque-type psoriasis: a multicenter cross-sectional study in Germany. 2008; 216(4):366-72. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML