-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics

p-ISSN: 2163-1433 e-ISSN: 2163-1441

2015; 5(5): 90-96

doi:10.5923/j.cmd.20150505.02

Relation between Fatigue and Leptin in Chronic Viral Hepatitis

Hanaa Mohammed Mahmoud Omar1, Abeer Mohammed Abul Ela1, Naglaa Atef Reyad Al-Gendy1, Hanaa Aboelyzied Aboelhassn2, Hala Taha Mohammed3, Olfat Mohamed Hendy4, Islam Abdelrahman Shahen5

1Tropical Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine (for girls), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

2Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine (for girls), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

3Psychiatric Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine (for girls), Al-Azhar University Cairo, Egypt

4Clinical Pathology Department, National Liver Institute, El-Menoufiya University, Egypt

5El abssia Fever, Hospital, Ministry of Health, Cairo, Egypt

Correspondence to: Naglaa Atef Reyad Al-Gendy, Tropical Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine (for girls), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

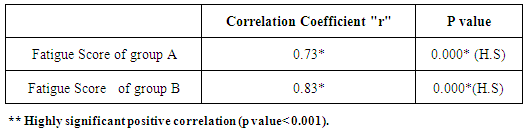

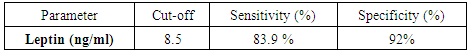

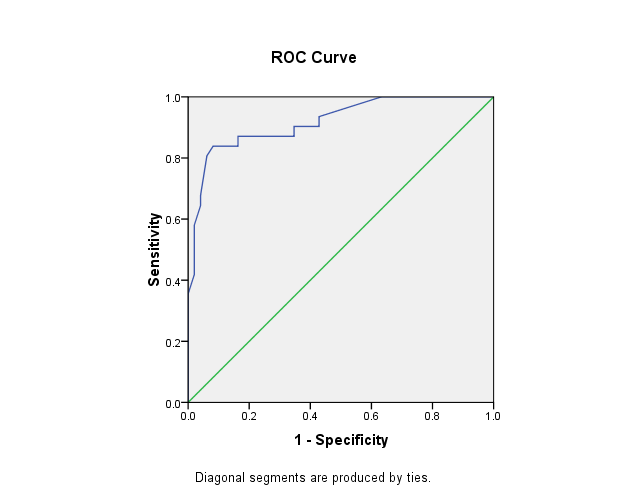

Background:Fatigue is characterized by a diminished ability to exert effort, usually associated with a feeling of being tired, bored, weak, and irritable. It is universal to all types of liver diseases, and does not necessarily correlate with the severity of liver disease. The studies concerning quality of life of patients with chronic viral hepatitis found a relationship between quality of life and the severity of the disease. Leptin is an important regulatory hormone of energy and homeostasis. It has been shown to modify the functional capacity of skeletal muscles, and induces a significant increase in diencephalic 5 hydroxytryptamine content. This raises the possibility of Leptin dependent mechanism for fatigue. Several studies showed that the circulating Leptin level is increased in cirrhosis. Leptin has been implicated in liver fibrogenesis and its level has been found to be elevated in patients with chronic hepatitis. Aim: Assessment of serum Leptin and its possible association with the presence of fatigue in chronic viral hepatitis patients. Also, find out the correlation between the serum level of Leptin and the severity of fatigue in an attempt to select the patients who need immediate measures to decrease the serum Leptin level and anti –viral treatment. Patients and Methods: A hospital based case control study was conducted on eighty subjects; twenty of them were patients with compensated HCV (group A), another twenty were patients with compensated HBV (group B) and 40 healthy individuals as a control group (group C). All groups were subjected to the following:Careful history taking, clinical examination, fatigue assessment by using the multidimensional assessment of a fatigue scale (MAF) and a measure of serum Leptin level by ELISA. Results: There was a highly significant increase in percentage of patients with fatigue and in fatigue severity in chronic viral hepatitis C patients when compared to control group. There was also increase fatigue severity in females when compared to males. There was no significant statistical difference between chronic viral hepatitis B patients and control group regarding the presence of fatigue; however, there was a significant increase in fatigue severity in chronic viral hepatitis B patients when compared to control group and a significant increase in fatigue severity in females when compared to males. There was a highly significant increase in Leptin level when comparing chronic viral hepatitis C patients with control group and with chronic viral hepatitis B patients. The sensitivity of Leptin in diagnosis of fatigue was 83.9% and the specificity was 92%, while the cut-off point was 8.5 ng/ml. Conclusions:Fatigue was present in 65% and 45% in chronic viral hepatitis C and B patients, respectively; it was more severe in females. Leptin level is elevated in patients with chronic HCV than patients with chronic HBV and the control group. Leptin had a significant positive correlation with fatigue score in chronic viral hepatitis. In chronic HBV females had higher levels of Leptin in comparison to males. The sensitivity of Leptin in diagnosis of fatigue was 83.9% and the specificity was 92% and its cut-off point was 8.5 ng/ml.

Keywords: Chronic viral hepatitis, Fatigue, Leptin

Cite this paper: Hanaa Mohammed Mahmoud Omar, Abeer Mohammed Abul Ela, Naglaa Atef Reyad Al-Gendy, Hanaa Aboelyzied Aboelhassn, Hala Taha Mohammed, Olfat Mohamed Hendy, Islam Abdelrahman Shahen, Relation between Fatigue and Leptin in Chronic Viral Hepatitis, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2015, pp. 90-96. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20150505.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Egypt has the highest HCV prevalence in the world [1, 2]. This unparalleled level of exposure to this infection appears to reflect a national level epidemic. It has been postulated that the epidemic has been caused by extensive iatrogenic transmission during the era of parenteral anti schistosomal therapy (PAT) mass-treatment campaigns [3, 4]. HCV infection and its complications are among the leading public health challenges in Egypt [5].Hepatitis B virus infection (HBV) is a worldwide problem and it is still the main factor of developing chronic HBV, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), especially in developing countries [6]. Hepatitis B virus is a serious global public health problem; studies in Middle East showed that the prevalence of HbsAg ranged from 3% to 11% in Egypt [7].Fatigue is a symptom characterized by a diminished ability to exert oneself. It is universal to all types of liver diseases. In some people, fatigue begins several years after the diagnosis of liver disease has been made but sometimes is an early symptom; it is the primary reason for seeking medical attention in the first place. Some people even seek psychiatric evaluation since depression often accompanies fatigue [8].Fatigue is reported in up to 67% of individuals with chronic HCV and is the most frequent extra_ hepatic manifestation in those patients [9], and it is reported more in females than males [10].Leptin is a circulating 16 KDa peptide hormone produced primarily in the adipo-cytes of white adipose tissue and the level of circulating Leptin is directly proportional with the total amount of fat in the body [11]. In addition to white adipose tissue—the major source of Leptin—it can also be produced by brown adipose tissue, placenta (syncytio- trophoblasts), ovaries, skeletal muscle, stomach (lower part of fundic glands), mammary epithelial cells, bone marrow, pituitary and liver [12].Leptin has also been discovered to be synthesized from gastric chief cell in the stomach [13], its receptors are present in the central nervous system in the hypothalamus [14]. Leptin is produced by hepatic stellate cells but only following their activation. Because activation of stellate cells is a central event in the fibrotic response to liver injury, Leptin may directly stimulate fibrogenesis in stellate cells [14]. Leptin has been increased in chronic hepatitis C patients and has been higher in females than males [10].Fatigue has been positively correlated with Leptin level, Leptin has been shown to modify the functional capacity of skeletal muscles, and induce significant increase in diencephalic 5 hydroxytryptamine content. This has raised the possibility of Leptin depending mechanism for fatigue [15].Aim of the study: Assessment of serum Leptin and its possible association with the presence of fatigue in chronic viral hepatitis patients. Also, find out the correlation between the serum level of Leptin and the severity of fatigue in an attempt to select patients who need immediate measures to decrease the serum Leptin level and anti –viral treatment.

2. Patients and Methods

- A hospital based case control study was performed in Al-Zahraa University Hospital, Cairo, Egypt, from February 2013 to January 2014.A simple random sample of 80 subjects (40 compensated chronic hepatitis patients admitted to the Tropical Medicine Department or attended its out-patient clinic and 40 healthy controls) was taken and classified into the following groups:-Group A: included 20 adult compensated patients with chronic hepatitis C virus; 13 males (65%) and 7 females (35%). They were diagnosed by detecting HCV Ab. and by PCR.Group B: included 20 adult compensated patients with chronic hepatitis B virus; 14 males (70%) and 6 females (30%).They were diagnosed by detecting HBs Ag. and by PCR.Group C: included 40 healthy subjects as a control Group; 14 males (35%) and 26 females (65%). They were free from hepatitis C and B viral infection which was proven by clinical examination, laboratory investigation and ultra-sound.Exclusion criteria: Patients with decompensated chronic liver disease, patients with other causes of chronic liver diseases, patients under treatment of viral hepatitis, subjects who had diet restriction for weight loss in the last three months, diabetic patients, chronic debilitating diseases (cardiac, malignancies, etc..), hypothyroidism patients, patients with abnormal renal function tests, patients who have loss of weight > 10% in the last month and obese patients: Body mass index > 30% and old debilitated patients.After explaining the purpose of the study, consent was taken from all groups to participate in the studyAll groups were subjected to the followingA) Careful history taking and Clinical examination:B) Fatigue assessment by using the multidimensional assessment of fatigue scale (MAF):The Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF) scale is a self-administered questionnaire to measure self-reported fatigue. It contains 16 items and measures four dimensions of fatigue: severity, distress, degree of interference in activities of daily living, and timing. Fourteen items contain numerical rating scales and two items have multiple-choice responses. It is a method of evaluating fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C only. This scale is designed to differentiate fatigue from clinical depression, since they share the same symptoms. MAF scale consists of short questions that require the subject to rate his or her level of fatigue [16].An Arabic version of this instrument was developed by forward translation into Arabic by 2 bilingual professional translators and the preliminary translation was revised and the reconciled version was then subjected to backward translation into English by another 2 bilingual professional translators. Both translations were compared and they were almost similar. The questionnaire was tested on 20 patients to assess clarity, appropriateness of wording, understand ability, and culture relevance of the translated version. No items were modified, omitted or added to the questionnaire. To assess reliability of the instrument: internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s alpha with result of 0.90. In addition, test retest reliability of the different items using correlation coefficient was done with an interval of one week and the results were ranging from0.75 to 0.90.To calculate the Global Fatigue Index (GFI): Convert item 15 to a 0-10 scale by multiplying each score by 2.5 and then sum the items 1, 2, 3, average 4-14, and the newly scored item 15. Scores are ranged from 1 (no fatigue) to 50 (severe fatigue). Do not assign a score to items 4-14 if the respondents indicated they do not do any activity for reasons other than fatigue." If the respondents select no fatigue on item 1, assign a zero to items 2-16. Item 16 is not included in the Global Fatigue Index [17].C) Calculation of body mass index: by measuring the height in meters, weight in kilograms and calculating the BMI using the following equation:BMI =the individual's body weight divided by the square height in meters A BMI of 18.5 to 25 indicates optimal weight; a BMI of lower than 18.5 suggests that the person is underweight while a number above 25 indicates that the person is overweight and a number above 30 suggests that the person is obese (over 40, morbidly obese) [18].D) Laboratory investigations: Liver function tests, complete blood count, hepatitis markers (HCV Abs, HBs Ag) using third generation enzyme-linked immune-sorbent assay (ELISA) test, polymerase chain reaction for HCV and HBV to confirm the diagnosis, renal function tests and assessment of (T.S.H).E) Abdominal ultra-sound:F) Assessment of serum Leptin by ELISA: Leptin ELISA Kit. The normal value of serum Leptin level by using Leptin ELISA in males is (3.84 ng / ml ± 1.79) and in females is (7.36 ng / ml ± 3.73) [19].G) Statistical analysis:− Data collected were reviewed, coding and statistical analysis of collected data were done by using SPSS program (statistical package of social science; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 16 for Microsoft Windows.− Descriptive statistic was done as follows: Mean and standard deviation were calculated to measure central tendency and dispersion of quantitative parametric data while median for quantitative non-parametric measures. Frequency of occurrence was calculated to measure qualitative data. − Comparing groups was done using:a. Chi-square-test (χ2): for comparison of qualitative data. b. Student t test to determine the significance in the difference between two parametric variables. c. Mann-Whitney U test to determine the significance in the difference between two non parametric variables. d. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for association between two variables. e. The level of significance was taken at p-value of < 0.05 with confidence level 95%.f. The results were represented in tables and graphs.

3. Results

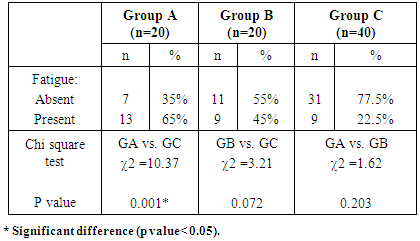

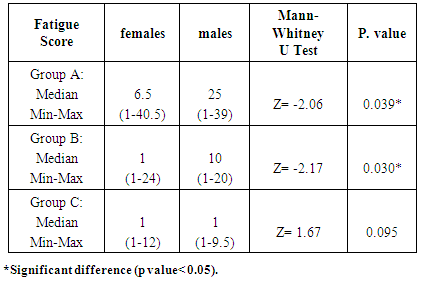

- In group A fatigue was present in 13 patients (65%) (Table 1), (7 males and 6 females). Regarding fatigue score, the median was 9.75, while the minimum and maximum were 1 and 40.50 respectively (Table 2), the median score in males was 25ranging from 1 to 39, while in females the median was 6.5 and ranging from 1 to 40.5 and there was a significant increase in fatigue severity in females when compared to males (Table 3).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Diagonal segments are produced by ties |

4. Discussion

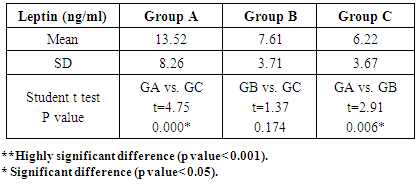

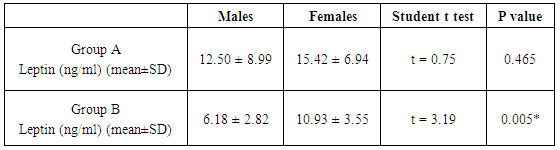

- Fatigue is characterized by a diminished ability to exert effort. It is universal to all types of liver diseases, and does not necessarily correlate with the severity of liver disease. In fact, fatigue may be just as debilitating to an individual in the early stages of liver disease, as in an individual with advanced cirrhosis [20].It is suggested that Leptin might play a role in the mediation of fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection [10, 21] as it modifies the functional capacity of skeletal muscle mass [22]. In the present study, fatigue was found in 13 patients of group A (65%) ,in 9 patients of group B (45%) and in 9 individuals of group C (22.5%), with a significant increase in the number of patients having fatigue in group A (65%) compared to group C.This was in agreement with Barkhuizen et al. [23] who found fatigue in 67% of HCV compensated patients. Piche et al., [10] (48.7%) and Poynard et al., [9] found that fatigue was present in 53%, but these results were less than those reported by El_Gindy et al., [21] and Hilsabeck et al. [24] who concluded that up to 100% of patients with compensated HCV reported significant fatigue at one time or another in the course of their disease.Discrepancy may be explained by the use of different systems for the classification of fatigue in the previous studies that varied from two classes (absence or presence of fatigue) as in Barkhuizen's [23] study to a specific fatigue scale as in Piche's [10] study that used fatigue impact scale. Poynard et al., [9] did not use any valid scoring system for fatigue while multidimensional assessment of fatigue scale was used in the present study. Also, fatigue criteria could be very variable according to different cultures.In the present study the presence and severity of fatigue were markedly higher in group A compared with group C. These findings were in agreement with El_Gindy et al., [21] whofound that fatigue in HCV cases was higher when compared to controls regarding the presence and severity of fatigue (P<0.01).Regarding fatigue score there was a highly significant increase in the fatigue score in group A when compared to group C. This was in agreement with Piche et al. [10] who performed a study on 78 HCV patients, 13 primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) patients and 22 healthy controls. They found that 38 of 78 HCV patients (48.7%), considered fatigue the worst or the initial symptom of their disease. The fatigue impact score of patients was significantly higher than that of controls (53.2 ± 40.1) vs. (17.7±16.9) (p<0.0001).In our study there was a significant increase in severity of fatigue in females compared to males in group A. This was in agreement with Piche et al. [10], who found that fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C was significantly more pronounced in females than in males (68.2± 41.2) vs. (41.6 ± 35.6); p=0.003). Poynard et al., [9] also found that in chronic hepatitis C patients, fatigue was associated with female gender. Hilsabeck et al., [24] found that female patients had an average fatigue level of 10.83 points higher than male patients.In our study there was also a significant increase in fatigue score in group B when compared to group C; there was also a significant increase in severity of fatigue in females compared to males in group B. This agreed with Meltem et al., [25] who found that the quality of life in hepatitis BV carriers was greatly similar to that of patients with chronic hepatitis BV and both groups have lower quality of life than normal population, with a significant increase in fatigue severity in females than males.Zhuang et al., [26] found that chronic hepatitis B patients suffered significant HRQoL (health related quality of life) impairment, the impairment reached a high level on mental health at the initial stage of illness and increased gradually with the disease progression to affect the physical health.In our study the presence and severity of fatigue was higher in group A than in group B, this is in agreement with Foster, [27] who found that patients with HCV had a more significant reduction in their quality of life than patients with chronic hepatitis B.In our study there was a highly significant increase in Leptin level in group A in comparison to group C. Our results were in agreement with Piche et al. [10] who found that the mean serum Leptin level was significantly higher in patients with CHC than in controls (15.4 ± 20.7) vs. (6.4 ± 4.1). Liu et al., [28] found that the serum Leptin level in patients with chronic hepatitis C (6.13 + /-3.94) ng/mL was significantly higher than that in controls (3.59 + /-3.44) ng/mL, EL_Gindy et al., [21] also found that serum Leptin level was significantly higher in CHC (24.9±28) ng/mL in comparison to the control subjects (14.8±8) ng/mL, Faggioni et al., [29] explained this by the tendency of circulating Leptin concentration to increase in CHC patients as an early signal of the loss of the ability to down-regulate energy expenditure in response to anorexia as chronic viral hepatitis progresses toward liver cirrhosis.Ghonemy et al., [30] also found elevated serum Leptin level in chronic liver disease patients; this could be due to the inflammation induced by chronic viral hepatitis. Moreover, inflammatory mediators such as interlukin-1 (IL1) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) stimulated Leptin secretion [31]. HCV infection interfered with fat and lipid metabolism in patients with chronic HCV infection, and the serum Leptin levels might be a reflection of the abnormalities in fat and lipid metabolism resulting from viral infection and related hepatic necro-inflammation [28].Leptin may also have a role in the progression of hepatic fibrosis. Firstly, Leptin increases the production of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), a potent pro-fibrogenic cytokine which up regulates the production of extra cellular matrix from hepatic stellate cells (HSC) [32]. Secondly, elevated Leptin levels may promote hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis [33]. This result disagreed with Eid and Abdelmaguid., [34] who included in their study of 40 CHC patients and 10 healthy controls that serum Leptin concentrations in CHC ranged from 0.4 to 72.8ng/ml with a mean of (14.9 ± 16.3) while in controls the range was from 2.8 to 11.1 ng/ml with mean (6.9 ± 3.0) with no significant difference between patients and control group. They explained that by the small number of control taken.We disagreed also with Tungtrongchitr et al., [35] who performed their study on twenty of each HBV, HCV and NASH patients compared with sixty people as the control group; they found that there was no statistical significant increase in circulating Leptin levels in CHC patients, when compared to the control group. Leptin level in CHC ranged from 2.3 to 34.2 ng/ml with mean level 7.9, while Leptin level in control ranged from 1.2 to 56 ng/ml with mean level 12.6.This might be due to that most of patients were males and there were suppressive androgens on Leptin.There was also a significant increase in Leptin level in group A when compared to group B, Tungtrongchitr et al., [35] also found that the mean Leptin level in HCV is increased than HBV group (7.9 vs. 7.65).There was no significant difference between males and females in Leptin level in group A, the reason for this discrepancy was not clear, perhaps this relation could not be elicited due to the small number of females included in the present study. On the contrary, Eid and Abdelmaguid, [34] who included 40 HCV patients and 10 healthy controls found that Leptin level was much higher in female patients (36.1 ± 23.6) than in males (10.4 ± 9.9) (P< 0.05), their study showed significantly higher serum Leptin level in HCV infected females. Piche et al., [10] study showed that when CHC compared with controls, absolute Leptin values were significantly increased in females (27.4 (25.0) vs. 8.7 (3.6) ng/ml; p=0.01) but not in males (6.9 (9.5) vs. 4.1 (3.2) ng/ml; NS). Also Saber et al., [36] found that serum Leptin was female gender dependent, they explained that women have significantly greater subcutaneous adipose tissue mass relative to omental adipose mass and estrogen increases serum Leptin levels while testosterone decreases them. Thus, patient’s sex needs to be considered when investigating Leptin levels.Leptin might mediate fatigue in chronic HCV patients by multi-factorial mechanisms. It modifies the functional capacity of skeletal muscle mass [15, 12] increases energy intake and expenditure [37], induces a significant increase in diencephalic 5-hydroxytryptamine content (serotonin) [38] leading to central fatigue during prolonged exercise [39] and induces sympathetic tone in humans leading to increase energy expenditure [40, 41].There was a significant increase in Leptin level in females when compared to males in group B. This was in agreement with Manolakopoulos et al., [42] who found that serum Leptin levels were significantly higher in females than in males in CHB( P= 0.05).In our study, we found a highly significant positive correlation between Leptin and fatigue score in group A, this result agreed with El_Gindy et al., [21] who found that serum Leptin levels were positively correlated to the severity of fatigue as assessed by a multidimensional assessment of fatigue score(r=0.25, p=<0.01). Also, Piche et al., [10] found that in patients with CHC, the total fatigue score was significantly correlated with Leptin levels (r=0.30, p=0.006). In group B there was a highly significant positive correlation between Leptin with fatigue score.The sensitivity of Leptin in diagnosis of fatigue was 83.9% and the specificity was 92% and its cut-off point was 8.5 ng/ml.

5. Conclusions

- Fatigue is present in 65% and 45% in chronic viral hepatitis C and B patients, respectively; it is more severe in females. Leptin level is elevated in patients with chronic HCV than patients with chronic HBV and the control group. Leptin has significant positive correlation with fatigue score in chronic viral hepatitis. In chronic HBV females had higher levels of Leptin in comparison to males. The sensitivity of leptin in diagnosis of fatigue was 83.9% and the specificity was 92% and its cut-off point was 8.5 ng/ml.

6. Recommendations

- Assessment of serum Leptin level in patients with other chronic liver diseases suffering from fatigue, and applying measures to decrease serum leptin could improve fatigue in patients with chronic viral hepatitis.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML