-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics

p-ISSN: 2163-1433 e-ISSN: 2163-1441

2014; 4(2): 17-22

doi:10.5923/j.cmd.20140402.01

Asthma: Opinion or Evidence Based Medicine?

Paolo Sossai 1, 2, Anna Maria Travaglione 3, Francesco Amenta 1

1Center of Clinical Research, School of Medicinal and Health Products Sciences, University of Camerino, Italy

2Department of Clinical Medicine, General Hospital of Urbino, Italy

3Department of Geriatric Sciences, General Hospital of Fano, Italy

Correspondence to: Paolo Sossai , Center of Clinical Research, School of Medicinal and Health Products Sciences, University of Camerino, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Asthma is a worldwide health problem affecting about 315 million persons. The clinical problem is the control of airway narrowing and inflammation. This control requires daily use of medications. Corticosteroids should be used also in children and this could be a significant problem for the possible side effects. Given that more than 50% of patients with asthma is poorly controlled, here we report a brief review about the more confident therapies using inhaled corticosteroids and long acting beta2 agonists. We also report the safety profile of these therapies.

Keywords: Asthma, Inhaled corticosteroids, Long acting beta2 agonists, Salmeterol, Fluticasone, Beclomethasone, Formoterol, Budesonide, Evidence-based medicine

Cite this paper: Paolo Sossai , Anna Maria Travaglione , Francesco Amenta , Asthma: Opinion or Evidence Based Medicine?, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 17-22. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20140402.01.

1. Introduction

- Asthma is a worldwide problem of public health affecting 315 million persons of all ages [1]. The disease affects people of all races and ethnic groups worldwide, from infancy to old age.Asthma is an inflammatory disorder characterized by bronchoconstriction and airway hyperreactivity, followed by inflammatory manifestations in the respiratory system. Chronic inflammation can lead to structural changes in the airways, including airway smooth muscle cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia [2-4]. These structural changes may underlie the irreversible component of airway narrowing that can increase over many years, particularly in patients with severe disease. In the 1970s and 1980s, severe asthmatic exacerbations and asthma-related mortality worrying rose [5]. Yet the most recently available data indicate improved outcomes, with fewer annual hospitalizations and fewer asthma-related deaths [6]. Among the possible explanations for these favorable trends are the more widespread preventive use of inhaled corticosteroids, the introduction of new effective medications and improved medication formulations for the treatment of asthma. Despite the availability of these effective therapies, over half of patients with asthma are yet poorly controlled. A possible explanation is that more than 80% of patients with uncontrolled asthma have poor adherence to medications [7]. In some cases the complexity of airway diseases like the overlap between asthma and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) constitutes another hurdle to predict the response to therapy [8]. Therefore, after significant efforts, the challenge to treat asthma still remains open. The main objective in asthma treatment is to achieve control of the clinical manifestations and maintain this control for prolonged periods to prevent worsening of disease. The concept of ‘asthma control’ is defined as ‘the extent to which the various manifestations of asthma have been reduced or removed by treatment’ [9]. This concept encompasses two components, the patient’s recent clinical status/current disease impact (symptoms, night awakenings, use of reliever medication and lung function) and future risk (exacerbations, decline in lung function or treatment related side effects). According to the GINA (Global INitiative for Asthma) Guidelines, asthma is controlled when a patient has daytime symptoms only twice or less per week, has no limitation of daily activities, has no nocturnal symptoms and no exacerbations, has normal or near normal lung function and uses reliever medication twice or less per week. GINA proposes a classification of asthma by level of control in three categories (controlled, partly controlled and uncontrolled). Once asthma control has been achieved, ongoing monitoring is essential to maintain control and to establish the lowest effective dose of treatment. According to the international guidelines, appropriate management of persistent asthma requires daily use of controller medications like inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). However, often, ICS are used intermittently by patients or recommended by physicians to be used only at the onset of exacerbations. The concept of symptom-based controller therapy is likely to become a new paradigm [10] but a recent Cochrane Review showed that daily use of inhaled glucocorticoids is superior to intermittent use with respect to good asthma control, airway inflammation, lung function, and need for rescue medication [11].

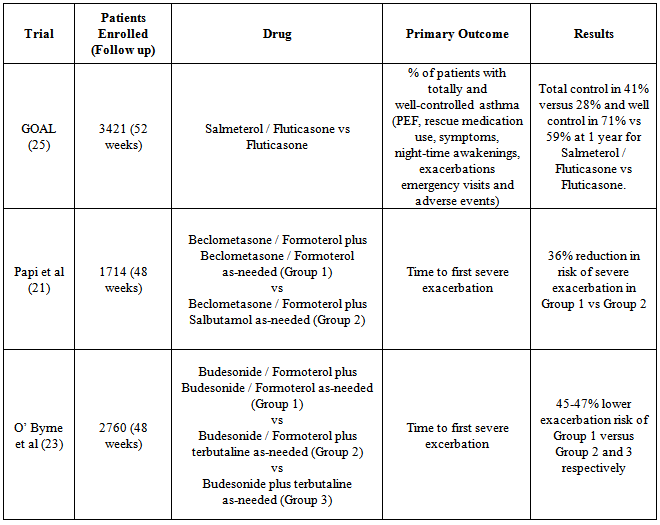

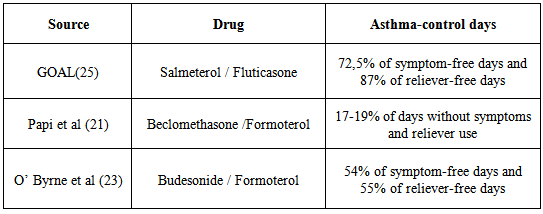

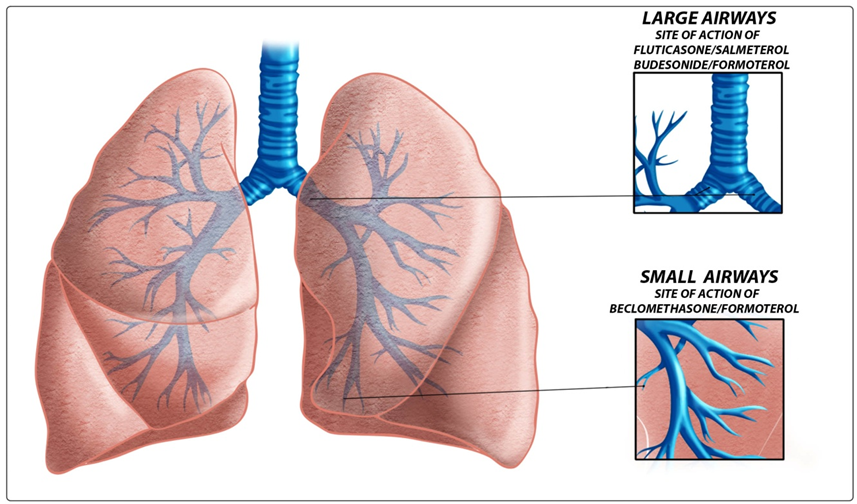

2. Comparison of Therapies

- Current guidelines recommend that inhaled corticosteroids are the first-line treatment in adults and children with persistent asthma. In 2011 two pragmatic trials performed in community settings biased by open label design and supported by LTRA (leukotriene-receptor antagonist)’s pharmaceutical companies, showed that at 2 months LTRA was equivalent to an inhaled glucocorticoid as first-line controller therapy and to Long Acting Beta Agonists (LABA) as add-on therapy but equivalence was not proved at 2 years [12].A recent Cochrane Review confirms that as monotherapy, inhaled corticosteroids display superior efficacy to anti-leukotrienes in adults and children with persistent asthma [13]. Bronchodilators are important for relieving bronchoconstriction and thus still remain major drugs for asthma. The fact that LABA administered by inhalation can provide improvement in lung function may tempt clinicians to use them as a long-term controller medication. However, without concomitant use of an inhaled corticosteroid, this strategy results in unsuppressed airway inflammation and an unacceptably risk of severe exacerbations and mortality. In February 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), implemented updated recommendations for the use of LABA therapy contraindicating the use of LABAs for asthma without concomitant use of an asthma-controller medication such as an ICS [14].For patients of any age in whom good asthma control is not achieved with the use of an inhaled corticosteroid, transition to a combination of an inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting beta-agonist is indicated as the most effective strategy. Although ICS-LABA combination inhalers are extensively used, there is increasing evidence that this may not be the complete answer for achieving optimal control. Among other drugs, anti-IgE monoclonal antibody, omalizumab, is the first biologic immunoregulatory agent available to treat severe asthmatics in several countries including the USA and UK. Mepolizumab, which in severe steroid-resistant asthma reduced asthma exacerbations significantly, and other compounds of different classes represent significant promises for future strategies in asthmatics [15]. The focus in the future could be to identify complementary strategies like, for example, the emerging role of probiotics in intestinal dysbiosis related to allergic disease [16] although two recent studies reveal no beneficial effects in primary prevention of allergic disease [17, 18]. Today there is another relevant question, particularly in asthma: are we still confident in Evidence Based Medicine or not? In the last years, small airways and the SMART (Single Maintenance and Reliever Therapy) strategy, seem to be a more relevant question than the value evidences of RCT (Randomised Controlled Trial) [19]. The small airways are currently a hot topic in pulmonary medicine, receiving renewed interest and attention regarding their role in asthma. The advent of formulations with extrafine particles of ICSs and ICS+LABA targeted to small airways has abruptly expanded the market in absence of long term evidences derived from clinical trials which compare newer agents versus traditional therapies . There is an undeniable tendency for the clinical benefits of each new agent to be overvalued at the point of entry to the market. The pharmaceutical companies seek to recover investments and profits from their licence at the earliest possible. New drugs enter the clinical arena with unrealistic assumptions as to efficacy and safety.RCT remain the gold standard to evaluate efficacy and safety of a drug.A 2013 note of EMA (European Medicines Agency) for Guidance on Clinical Investigation of Medicinal Products for Treatment of Asthma states that claims for chronic treatment with controller medication should be supported by the results from randomised, double blind, parallel group, controlled clinical trials of at least six months duration. The first long and large RCT of an extrafine drug was a flop [20]. In mild asthma, compared with placebo, in 52 weeks RCT, the time to first severe asthma exacerbation (the primary variable) was not prolonged with ciclesonide, an extrafine ICS.Considering the three main ICS-LABA combinations (fluticasone/salmeterol, budesonide/formoterol, beclometha- ne/formoterol), we selected for each combination the RCT with greater number of patients and longer follow-up. The search for these studies was carried out using as source PubMed (US National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health). The results are reported in the tables and discussed below.Papi et al [21] reported that beclomethasone–formoterol extrafine for both maintenance and reliever treatment is superior to beclomethasone–formoterol extrafine for maintenance plus salbutamol as needed in terms of reduction of exacerbations in patients with asthma. Finally the authors suggested that these results provide encouraging data for the formulation of beclomethasone–formoterol for this use. Our opinion is that these conclusions are misleading and minimizes relevant questions like asthma control and symptom control. In fact, a closer look at the trial’s data surprisingly reveals that asthma control with beclomethasone-formoterol remains low in both groups (less of 20% of days with no asthma symptoms and no use of as-needed medication). The frequent use (0,7 inhalations/day) of reliever medication is an acceptable clinical endpoint that reflects lack of asthma control. Similar results (0.92 inhalations/day) were obtained in a review by Chapman et al. of budesonide/formoterol fine combination used as single maintenance and reliever therapy (SMART) with only 17.1% of patients controlled and more than half of days (weighted average 54.0% of days) with asthma symptoms in 6-12 months of follow up [22]. With SMART, the best results come from O’ Byrne’s study that does not exceed 54% of symptom-free days [23].Fashions can sometimes be dangerous for the health of people. The strategy of use the same inhaler for both maintenance and reliever therapy with extrafine beclomethasone-formoterol or fine budesonide/formoterol (by many people considered driven by mainly commercial and financial interests), is intriguing but is important to remember a famous Churchill’s dogma “however beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results” [24].When quick-acting bronchodilators are needed for symptom relief more than 2 days per week we have not “good control” of asthma. Different composite scores have been developed to measure “asthma control”, using categorical or numerical variables but unfortunately to date we have only a 1 year randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study of 3,421 patients with uncontrolled asthma that compared two drugs (see Table 1) in achieving two rigorous, composite, guideline-based measures of control: totally and well-controlled asthma [25].In GOAL study, a regular treatment based on fluticasone-salmeterol plus salbutamol as needed provided a well-controlled asthma in about 70% of patients at 1 year, with 72,5% of days without symptoms and about 87% of days without rescue medication [26] (see Table 2).In a 1-year head to head, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy study (CONCEPT), patients with symptomatic asthma receiving salmeterol/fluticasone had a significantly greater percentage of symptom-free days (primary end point) compared with those receiving budesonide/formoterol (median, 58.8% vs 52.1%, respectively; p= 0.034) and a significantly 47% lower incidence of exacerbations requiring oral steroids or an emergency department (ED) visit/hospitalization ( p = 0.008) [27]. Several reasons can explain the clinical differences among fluticasone-salmeterol and other LABA/ICS therapies, for example beclomethasone / formoterol. Beclomethasone-formoterol is an extrafine formulation while fluticasone-salmeterol simply fine. Aerosol particle size influences the extent, distribution, and site of inhaled drug deposition within the airways. The smaller particle size of the beclomethasone/formoterol combination, compared to fluticasone/salmeterol combination which is formulated with larger particles, enables the ICS and LABA to reach principally the small airways (see Figure 1).

|

|

| Figure 1. Sites of action of the principal ICS-LABA combinations |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML