-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics

p-ISSN: 2163-1433 e-ISSN: 2163-1441

2013; 3(2): 29-51

doi:10.5923/j.cmd.20130302.03

Emergency Obstetric Care: Urban Versus Rural Comparison of Health Workers’ Knowledge, Attitude and Practice in River State, Nigeria- Implications for Maternal Health Care in Rivers State

Ebuehi Olufunke Margaret1, Chinda Grace Nkechinyere2, Sotunde Oludolapo Muibat3, Oyetoyan Solomon Adeyanju4

1Reproductive and International Health Unit, Department of Community Health and Primary Care College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria

2Rivers State Ministry of Health, Port Harcourt, Rivers State

3Primary Health Care Department, Local Government Secretariat, Lagos Mainland Local Government, Lagos State

4Primary Health Care Department, Local Government Secretariat, Badagry Local Government, Lagos State

Correspondence to: Ebuehi Olufunke Margaret, Reproductive and International Health Unit, Department of Community Health and Primary Care College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In Nigeria, an estimated 545 maternal deaths occur for every 100,000 live births. Within the country, gaps exist between urban and rural areas, with more maternal deaths occurring in the rural areas. The knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of Emergency Obstetric care (EmOC) among health care providers, are important determinants of the quality and outcome of care. The study determined and compared the KAP of EmOC among health care providers in urban and rural public secondary health facilities in River state, South-south Nigeria; and also assessed the availability of resources for EmOC provision.Information was obtained from 304 doctors and nurses, using a pre-tested, self-administered questionnaire and a facility checklist was used to obtain relevant information about resource availability for EmOC in 13 health facilities. Data were analysed using EPI-INFO version 3.5.1. Findings showed that more (28.9%) respondents from urban facilities had good knowledge of EmOC than their rural counterparts (16.4%). More respondents (96.1%) from rural facilities had positive attitude compared to the urban counterparts, (93.4%), however more urban respondents (77%) reported good practice compared to 40.8% in rural facilities. Approximately a third of respondents (urban: 28.5%, rural: 33.1%) reported having obstetric protocols in their facilities. A mean of 7.5 obstetricians/gynecologists were employed in the 4 urban compared to 0.3 in the 9 rural facilities. More deficits in meeting the criteria for Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric Care (CEmOC) were seen in the rural than the urban facilities; as at study time, all rural facilities neither had capacity for managing complications that could arise from pregnancy-induced hypertension nor a blood bank. Findings revealed that urban health workers demonstrated better knowledge and practices than their rural counterparts. Resources were inadequate in both areas albeit better in urban facilities. Regular training and re-training of staff on EmOC, with adequate and equitable distribution of resources between urban and rural facilities is recommended.

Keywords: Emergency Obstetric Care (EmOc), Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, Urban and Rural

Cite this paper: Ebuehi Olufunke Margaret, Chinda Grace Nkechinyere, Sotunde Oludolapo Muibat, Oyetoyan Solomon Adeyanju, Emergency Obstetric Care: Urban Versus Rural Comparison of Health Workers’ Knowledge, Attitude and Practice in River State, Nigeria- Implications for Maternal Health Care in Rivers State, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 29-51. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20130302.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Combating maternal mortality and morbidity is a global problem that demands policies and political commitments; strategy formulation and implementation; and improved health care service delivery and management. There is now an international consensus that making pregnancy and delivery safer includes ensuring that women, who experience obstetric complications, receive the medical care they need on time. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) has identified Emergency Obstetric Care (EmOC), to ensure timely access to care for women experiencing complications as one of the three strategies to reducing maternal mortality[1]. The other two strategies are family planning to ensure that every birth is wanted and skilled care by a health professional with midwifery skills, for every pregnant woman during pregnancy and childbirth.Emergency obstetric care (EmOC) is defined as a set of life saving services that must be available in health facilities to respond to emergencies that arise during pregnancy, delivery or postpartum.[2] Emergency services are needed to handle potentially life-threatening, direct obstetric complications that affect an estimated 15% of women during pregnancy, at delivery, or in the postpartum period even in developed countries[3]. ‘About fifteen per cent of all pregnancies will result in complications. Most complications occur randomly across all pregnancies, both high- and low-risk. They cannot be accurately predicted and most often cannot be prevented, but they can be treated’[1]In 1987, the Safe Motherhood Initiative was launched; it sought to reduce the burden of maternal mortality especially in developing countries. In the application and implementation of these strategies, undue emphasis was placed on predicting and preventing obstetric complications, rather than effective and efficient management of these complications when they arise. While today, strategies are more appropriately focused. It is essential that pregnant women in whom complications develop have access to the medical interventions of emergency obstetric care to ensure favourable maternal and foetal outcomes.Research has shown that for every maternal death, there is a potential death of a child, increase in child labour, illness, malnutrition, social isolation and poor hygiene[4],[5]. There is also, dissolution and reconstitution of the family unit, reduced productivity and loss of output.[4] An estimated figure of over five hundred thousand (>500,000) women die yearly from pregnancy related complications, about ninety nine percent (99%)[4] of these deaths take place in developing countries; where a woman’s lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy and related complications is almost 40 times greater than that of her counterparts in developed countries.[4] It has also been noted that “for every woman who dies, an estimated 15 to 30 women suffer from chronic illnesses or injuries as a result of their pregnancies”[1] all of these are preventable. Nearly all these lives could be saved if affordable, good-quality obstetric care were available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.[1]The 2008 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey estimated maternal mortality ratio to be 545 deaths per 100,000 live births.[6] These deaths are due to direct and indirect obstetric complications with the direct complications accounting for about seventy five percent (75%)[7] of maternal deaths in the developing countries. Eighty six percent (86%) of these direct obstetric deaths are caused by five major medical complications: haemorrhage (28%); complications of unsafe abortion (19%); pregnancy-induced hypertension (17%); obstructed labour (11%); and infection (11%).[7] A complication can be defined in practical terms as an event of sufficient severity that staff must respond with a life-saving procedure or referral to another facility. The response required for these direct obstetric complications have been identified as the “signal functions of emergency obstetric care”.The fifth (5th) Millennium Development Goal is aimed at improving maternal health through reduction of maternal mortality and provision of universal access to reproductive health by 2015. It seeks to achieve a 5.5% annual decline in MMR from 1990 levels. Globally the annual percentage decline in MMR between 1990 and 2008 was only 2.3% thus making the attainment of the goal difficult.[5]The maternal mortality ratio in Nigeria is unacceptably high and should be a concern of every Nigerian at all levels of governance; policymaking and implementation; service delivery and management. Maternal mortality reduction has been described as a key developmental goal (MDG 5) and as a basic human right. If staff in a facility cannot recognize a condition that requires an emergency action, quality of care will be undermined;[2] it is worse tragedy if these conditions are identified and yet there is a “want” of skill or knowledge of what to do.

1.1. Review of Some Studies done in Nigeria

- A study done in Osun and Ekiti states in Nigeria, among primary and secondary levels obstetric care providers, revealed a poor knowledge of EmOC. An alarming 91% of providers had poor knowledge of the concept. The study also assessed the operatives’ preferred strategies and practices for safe motherhood and averting maternal mortality; 70% of respondents still preferred the strengthening of routine ANC services to the provision of access to EmOC for all pregnant women who need it. There was gross disparity in what is said to be practiced and what was actually practiced based on the structured observations done, 40% of the staff reported counseling clients on complication readiness but the structured observation revealed no staff did. Only 9% of the staff had ever been trained in life saving skills.[8]In another study done also in South- West geo-political zone of Nigeria, only 32.3% of obstetric care providers used partograph in monitoring labour, and only 37.3% of obstetric care providers, who were predominantly from tertiary level of care, could correctly mention at least one component of the partograph. The partograph is a cheap and efficient tool for monitoring active phase of labour, and aids early detection and prompt management of obstetric complications. It is a mandatory intra-partum tool for all health facilities providing maternity services in the Women and Child Friendly Health Services (WCFHS) initiative.[9]In yet another study done in the South-West region of Nigeria to assess the changing patterns of critical obstetric care, a two consecutive 3 year period retrospective study was done. In this study, the definition of near miss morbidity was based on validated disease-specific criteria. Results revealed 175 near misses and 27 maternal deaths in 1999–2001 and 211 near misses and 44 maternal deaths in 2002–2004. The “critically ill obstetric patient”- cause specific case fatality rates (CIOP-CFRs) for the two periods showed a declining (but non-significant) trend in the standard of emergency obstetric care for life-threatening conditions (13.4% to 17.3%, P=0.250). The CIOP-CFR for postpartum hemorrhage significantly increased from 3.1% to 21.1% in the 2nd period (P=0.033), reflecting a decline in the standard of care. Lack of blood for transfusion became a more significant administrative problem in the 2nd period occurring in 17.8% of all critically ill patients managed in 2002–2004. There was a notable though statistically insignificant increase in the non-adherence to treatment protocol among cases of maternal death in 2002–2004 compared with 1999–2001.[10]A nationwide survey of availability of basic emergency obstetric care (BEmOC) in primary healthcare centers with midwives service scheme (MSS) in rural areas in Nigeria revealed that a mean of 70% of the centers had access to antibiotics for the treatment of uncomplicated sepsis; 11% were conducting vacuum extraction; 21% were able to perform manual vacuum aspiration. Only 40% initiated treatment for pre-eclampsia, and 28% for eclampsia. 36.8% had provision for post abortion care; South-south zone had only less than third of their PHC delivering post abortion care; 21% had a functional manual vacuum aspirator set. The south-south zone had the least of these devices. 30% of midwives service scheme PHC were not treating women with uncomplicated sepsis. 27% had magnesium sulphate (MgSO4) available; 30% had misoprostol tablets and 12% had anti-shock garment[11].Similarly, a pre-intervention needs assessment done in a local government of South-West Nigeria revealed a want in skilled health workers in health facilities. A good proportion of health facilities (46%) were manned by unskilled health workers, and there was wide spread lack of equipment and supplies. No facility met the criteria for a basic essential obstetric care; only one private facility (3.8%) met the criteria for a comprehensive essential obstetric care.[9]

1.2. Review of Some Studies done outside Nigeria

- A study done in Kenya, East Africa, which looked at health workers’ preparedness in the provision of EmOCexploring the comprehensive knowledge of action to take in the event of retained placenta, unsafe abortion and postpartum haemorrhage. Findings revealed that Less than 25% (<1/4) had good knowledge on what to do in the event of retained placenta and there was great disparity between hospital-based health workers (40%) and clinic and dispensary health workers (6%). Similarly, there was poor knowledge on post abortion care, with only 14% of health workers sampled having good knowledge. There was fair performance on quality of care to be provided in the event of postpartum haemorrhage: 42% of hospital-based workers had good knowledge, 21.3% and 6.3% respectively of health center, and clinic and dispensary workers had good knowledge.[12]In a study done in New South Wales to assess the availability of postpartum haemorrhage protocol in health facilities; 94% of facilities that provided maternity services had protocols. Of these 94% facilities, 22% of the facilities had protocols that contained incorrect definition of PPH. Only 71% of the respondents from small rural and urban facilities received a copy of the protocol.[13]Similarly, in Zambia few health facilities provided the complete BEmOC (12%) and qualified professionals available 24hours per day. There is an urban/rural disparity in the distribution of health professionals with the urban provinces having more doctors and midwives, while some rural province do not even have one health professional. Only 42% of the facilities employed more than two doctors in their facility[14]Of the 1131 Zambian delivery facilities, 135 (12%) were classified as providing EmOC. Zambia nearly met the UN EmOC density benchmarks nationally, but EmOC facilities and health professionals were unevenly distributed between provinces. Geographic access to EmOC services in rural areas was low; in most provinces, less than 25% of the population lived within 15 km of an EmOC facility.In another study done in Zimbabwe, it was found that only 26.1% of the hospitals fulfilled the criteria for CEmOC. Main reasons found for non-fulfillment were: shortage of drugs (including blood and blood products) in 54.1% (20/53), unavailability of equipment in 21.6% (8/53), and shortage of skills in18.9% (7/53).[15]Malawi had similar pattern like other Southern African countries, the signal function which required specific manual skills and specific equipment were the least available. Only 3.3% (2/60) of health facilities could perform vacuum extractions, 3.1% (2/60) could perform manual vacuum aspiration for retained products of conception, and 35% performed manual removal of placenta.[16]

1.3. Justification for the Study

- The Nigerian National Reproductive Health Policy of 2001 targeted a 50% reduction in maternal mortality from a national average of about 800 deaths to 400 deaths/100,000 live births between 2001 and 2006, a 50% increase in access to safe blood transfusion services, EmOC for women of reproductive age and reproductive health information and services. 17Nigeria is also a signatory to the Millennium Development Goals (MGDs) of the United Nations member countries, goal 5 of which targets the reduction of maternal mortality by 75% between 1990 and 2015 18, and the African Roadmap for the accelerated achievement of this goal. However, the country has made insufficient progress in the reduction of maternal mortality, with an annual percentage decline of MMR of 1.5%,5 the attainment of 75% reduction of 1990 levels by 2015 is a dismal goal. EmOC is an intra-partum strategy developed to help developing countries improve maternal health; if properly implemented, it is estimated to reduce maternal mortality by a quarter. While innovative programmes are ongoing in a number of states and local government areas with the support of UN agencies, bilateral donors, non-governmental organizations and the private sector, there is little concomitant political will on the part of political leaders who control resources, especially with regards to the placement, training and retention of skilled staff in public health facilities.1 It is therefore difficult to translate globally proven and effective remedies and technologies into action. The United Nations process indicator for EmOC3 is a set of monitoring tool developed to evaluate the progress of EmOC strategy. Availability of EmOC facilities involves: the structure, manpower, equipment, materials and supplies. If others are available and manpower of the right mix, with the right skill is not available, the quality of service delivered will be inadequate and the desired goal of the strategy will not be achieved. This study attempted to provide useful information on the knowledge, attitude and practice of health care providers on EmOC and the availability of resources for the provision of these services in public secondary health facilities in Rivers State. This thus assesses the current situation of the implementation of the EmOC strategy in Rivers State viz a viz rural-urban comparison and thus indirectly assessing the River state government’s efforts at meeting the MDG 5.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Location

- The study was done in Rivers State, located in the South-South geopolitical zone of Nigeria. It was created from the then Eastern region by Decree No. 19 of the 1967. Before then, the territory was referred to as Oil Rivers Protectorate; a name derived from its abundant wealth in oil and gas deposits. It accounts for over 48% of crude oil produced on-shore in the country, and 100% of the liquefied gas export for Nigeria. The strategic importance of Rivers state in the economy of Nigeria, earned it the name, the treasure base of the nation.The state is bounded on the south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the north by Anambra, Enugu, Ebonyi, Imo, and Abia states; on the east by AkwaIbom and Cross River states; and on the west by Bayelsa and Delta states. With a tropical climate, numerous rivers and vast area of land, the people of Rivers state have lived up to their tradition of agriculture, especially fishing and farming, commerce and industry.[20]The state has a population of about five (5) million people according to the National Populations Commissions, 2005.[21]Rivers state with twenty three (23) local government areas has thirty eight (38) public secondary health facilities with each LGA having at least one. Out of the 38 public secondary facilities, there are 15 in urban areas and 23 in rural. Four (4) of the secondary facilities in urban centers do not provide maternity services; they are specialist centers and clinics, this brings the eligible facilities to a total of 34.There are a total of 183 doctors and 1,068 nurses/midwives in the eligible facilities, with the urban centers accounting for 121 doctors and 625 nurses/midwives; and the rural centers accounting for 62 doctors and 443 nurses/midwives.[22]

2.2. Study Design

- A comparative cross sectional design, exploring the knowledge, attitude and practice of obstetric care providers about emergency obstetric care.

2.3. Study Population

- This consists of doctors and nurses/midwives in government owned public secondary facilities in rural and urban areas in Rivers State.

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- All government owned public secondary health facilities offering maternity services were included in the study.All doctors, midwives, and nurses who have been in their present unit (i.e. maternity unit) or facility in the last one year prior to the study were included.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- All government owned secondary health facilities not managed by the hospitals management board of the state were excludedAll doctors and nurses on training course and have not worked in the maternity unit for one completed year prior to the study.

2.4. Sampling Methodology

- Multi-stage sampling was employed to recruit respondents in this study as described:

2.4.1. Stage 1: Selection of Facilities

- There are 34 public secondary facilities eligible for this study; 11 urban and 23 rural. So, the facilities were picked in an urban/rural ratio of 1:2.The average staff strength for the urban and rural health facilities were 40 and 20 respectively; therefore to obtain 152 respondents in both areas, a simple random sampling method was used in the selection of 4 urban and 9 rural facilities. An additional rural facility was selected to make up for the skewed distribution of health care providers in the rural settings.

2.4.2. Selection of Respondents

- A simple random sampling method was applied in the selection of respondents at each facility. The number of respondents required for each urban facility was 38 (152/4) while for rural facilities it is approximately 17 (152/9) respondents per facility. At the facilities, a list containing the names of doctor and nurses/midwives was obtained from the management and by balloting 38 respondents for each urban and 17 for each rural facility were selected for the study.A facility checklist was administered in every facility selected for availability of resources in the labour ward, theatre and pharmacy units.

2.5. Data Collection Tools and Techniques

- The data was collected with two survey instruments: the health worker KAP questionnaire and a facility check list, from primary source by employing quantitative technique over an estimated three weeks period (March –April 2012) . The self- administered, questionnaire (adapted from a similar study done in South-West, Nigeria.[8]) was administered to the respondents while at work. The questionnaire had four sections – The first section obtained data on the socio-demographics of the respondents, section 2 on their knowledge, third section on their attitude, and the fourth on their practices regarding EmOC. There were a total of 34 questions, 9 on socio-demographics, 11 on knowledge, 6 on attitude, and 8 on practice. The eleven (11) knowledge questions required respondents to choose either “YES” or“NO” option on their awareness of EmOC, sub-types of EmOC, components/ signal functions of EmOC, awareness of obstetric complications, the major direct and indirect obstetric complications, awareness of the term “life saving skills” (LSS) and if they have been trained on any of the skills, elements of prenatal care and how they are ranked. There are six (6) attitude questions in which respondents were to choose whether a particular practice, intervention or strategy was “Not Effective”, “Barely Effective”, “Fairly Effective” or “Very Effective” in maternal health service delivery. The questions included: antenatal prediction and prevention of obstetric complications and death, EmOC in improving maternal health and reduction of maternal mortality, the effect of training and re-fresher courses on EmOC delivery, administration of oxytocin, controlled cord traction and uterine massage are in the management of retained placenta, and referral of a complicated case by a skilled birth attendant with LLS training. The eight (8) practice questions required respondents to choose from options that were listed under various practices such as: routine use of partograph, availability and use of obstetric protocols, management of retained placenta and management of severe hypertension in pregnancy. Also, they were required to indicate interventions, or treatments they have performed in the last three months prior to the study from a list of interventions and treatments listed in the questionnaire. In addition, the facility checklist (adapted from UNFPA checklist for planners1 and supervision checklist of the Ministry of health, Malawi[24]) was used to collect information on the availability of resources (human and material) in the thirteen facilities visited. This was applied in three areas: the labour ward, the theatre and the pharmacy units; using a walk-through- survey technique. The head of each unit or any person delegated by the head or the management of the facility took an interviewer through each unit, showing him/her the equipment and supplies itemized on the checklist. The interviewer indicated Yes or No, depending whether they were available or not and the number for human resources. The interviewer was also required to make remarks, for instance if an equipment is working or not; and any explanation provided by the guide. There were two sections: section A, human resource, had six (6) items; section B, material and supplies, had three sub-sections. B1 - labour ward with 31 items; B2 - theatre with 22 items and sub- items; and B3 – pharmacy unit with 12 items.

2.5.1. Pretest

- The questionnaire and facility checklist were pretested in two public secondary health facilities, one in each setting (urban/rural) in Lagos state to identify and correct possible flaws and ambiguity in the questionnaire. Twenty (20) respondents for each facility were randomly selected and questionnaires were administered. The facility checklist was also administered in each of the facilities.

2.5.2. Training of Research Assistants

- Six research assistants were selected to assist in data collection: two medical doctors, four field workers with minimum of secondary education. They were trained on the use of the questionnaire and checklist and also practiced simple random sampling for respondents at the facility level.

2.6. Data Analysis

- Completed questionnaires were checked for completeness, errors and inconsistencies. Errors and inconsistent entries detected were verified and corrected by the concerned interviewers.The Epi info statistical software; 2008 version was used for data entry, validation, cleaning and analysis.Data presentation was done in frequency tables, percentages, means and standard deviations (SD). Student’s T-test was used to compare means in the two groups. Chi square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine significant association between variables. Statistical significance was set at P< 0.05. To assess the participants’ knowledge, attitude and practice of EmOC, relevant questions from the questionnaire had weight attached to them to create composite scores.

2.6.1. Scoring Method

- For every correct option in knowledge and practice, a score of one (1) was assigned and every wrong option was scored zero (0). Interpretation of scores will be based on an adapted and modified Generic Grading Scale for Higher Education.[25] Respondents whose scores translates to greater than 66% were classified as having good knowledge of EmOC; those who scored between 34% and 66% were classified as having fair knowledge; those who scored between 0% and 33% were classified as having poor knowledge. Similar scoring was applied for practice; scores >60% were classified as good practice and <60% was poor practice.For attitude questions, modified Likert scale 0-1 was applied in the attitude question. Scores 0%-60% was classified as negative attitude and scores greater than 60% as positive attitude.Checklist for human resources was used to obtain the numbers on obstetricians/gynecologists,anesthesiologists/a nesthetic nurses, general practitioners with midwifery skills, midwives, nurses, pharmacists/pharmacy technicians, laboratory scientist/technicians in each facility visited. The mean and standard deviations for each staff type was calculated and the student’s T-test was used to compare means in urban and rural facilities.Material resources were recorded as available or not available, the numbers of facilities where a particular item was available was used to calculate percentage availability of each item in urban and rural areas. Then Chi-square was used to find the significance of association in the two settings.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

- Ethical clearance was obtained from the Health Research and Ethics Committee, Lagos University Teaching Hospital. Permission was obtained from the Hospitals Management Board, Rivers state, before proceeding to carry out this study.Confidentiality of respondents was ensured; names were not required on the questionnaires. A written consent form was administered to all respondents.

2.8. Limitation of the Study

- Only government secondary health facilities were used, so the study may not be a true picture of all secondary health facilities in the study area.The study design did not include other health workers that are not doctors and nurses.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Occupational Characteristics of Respondents

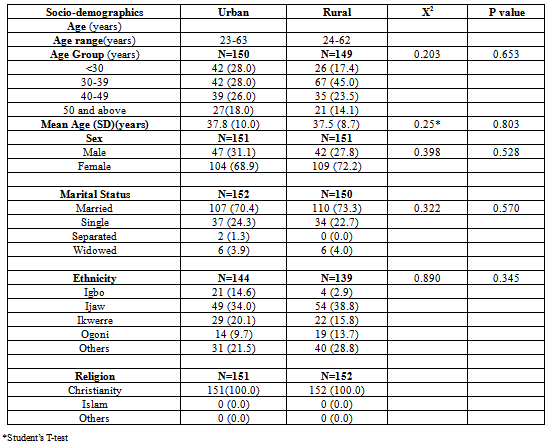

- The age range of the urban and rural respondents were between 23 and 63 years and between 24 and 62 years respectively. More than three quarters of the respondents (82%(urban) and 85.9% (rural)) in both areas, were below 50 years. The mean age of respondents in the urban and rural areas were 37.8 (+10.0) years and 37.5 (+ 8.7) years respectively. There is no statistically significant difference in the mean ages of the respondents from both areas (p-value=0.803).More than two thirds ((68.9%, [urban] and (72.2%, [rural]) of the respondents in both settings are females. There is no significant difference in the sexes of respondents in both settings (p-value= 0.528).Approximately seven out of ten respondents from both (70.4% [urban], (73.3%) [rural]) settings are married. There is no statistically significant difference in marital status among respondents in both urban and rural settings (p-value =0.570). All the respondents in both settings are Christians (Table 1).

|

|

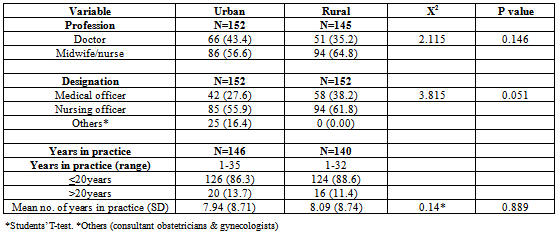

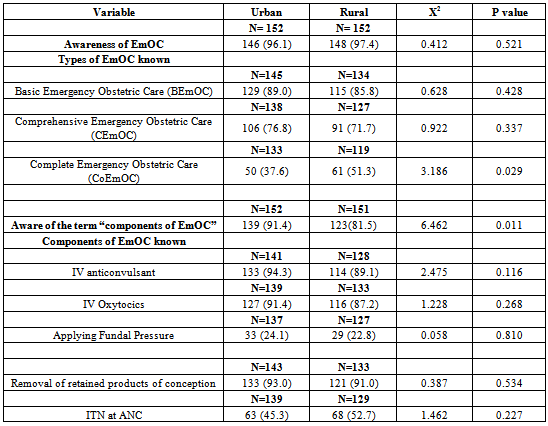

3.2. Respondents’ Knowledge of EmOC

|

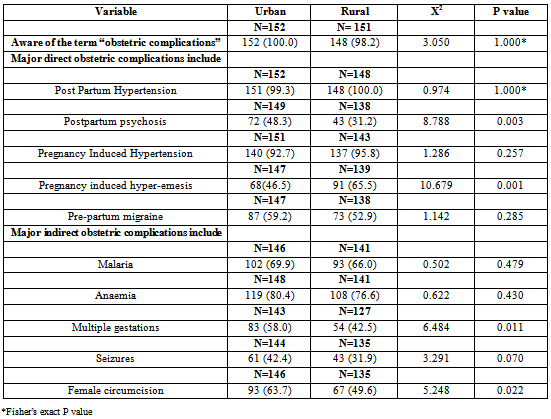

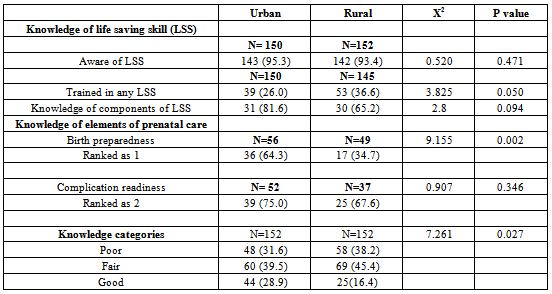

3.3. Respondents’ Knowledge of Obstetric Complications, Life Saving Skills and Elements of Prenatal Care

- The awareness of the term “obstetric complications” was very high among respondents both areas; Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) were identified by majority of the respondents as major obstetric complication. More rural, 91 (65.5%) than urban, 68(46.3%), p=0.001) respondents erroneously identified pregnancy induced hyper-emesis as being a major direct obstetric complication. The knowledge of major indirect obstetric complications was similar in both settings except for multiple gestations and female circumcision that were wrongly identified as major obstetrics complications by more rural than urban respondents. There were significant differences in the knowledge of these complications among respondents in urban and rural areas (p= 0.011 for multiple gestations and p=0.022 for female circumcision). More urban compared to rural respondents knew these were not major indirect obstetric complications, indicating a positive association of this knowledge with the urban areas (Table 4).The awareness of the term “life saving skills” (LSS) was high among the respondents, 143 (95.3%) urban and 142 (93.4%) rural were aware of the term. More rural, 53 (36.6%) compared to urban, 39 (26.0%) respondents reported to have been trained in (LSS) p=0.05). Majority of those that were trained in LSS had good knowledge of the components of LSS; 81.6% urban and 65.2% rural respondents p=0.094). Respondents were required to rank the elements of prenatal care, the most important as 1 and the next as 2. Only 36 (64.3%) urban and 17 (34.7%) rural respondents ranked birth preparedness as 1 and this difference in ranking was statistically significant different (p=0.002), more urban compared to rural respondents ranked birth preparedness properly. Thirty-nine (75.0%) urban and 25 (67.6%) rural respondents ranked complication readiness as 2 (p=0.346).Good knowledge of EmOC was demonstrated by 44 (28.9%) urban and 25 (16.4%) rural respondents. More rural than urban respondents demonstrated fair knowledge of EmOC; while 48 (31.6%) of urban and 58(38.2%) of rural respondents demonstrated poor knowledge of the concept (Table 5).There is statistically significant difference in the level of knowledge of EmOC among urban and rural respondents (P = 0.027); more urban compared to rural respondents had good knowledge of EmOC. Good knowledge of EmOC is positively associated with urban areas (Table 5).

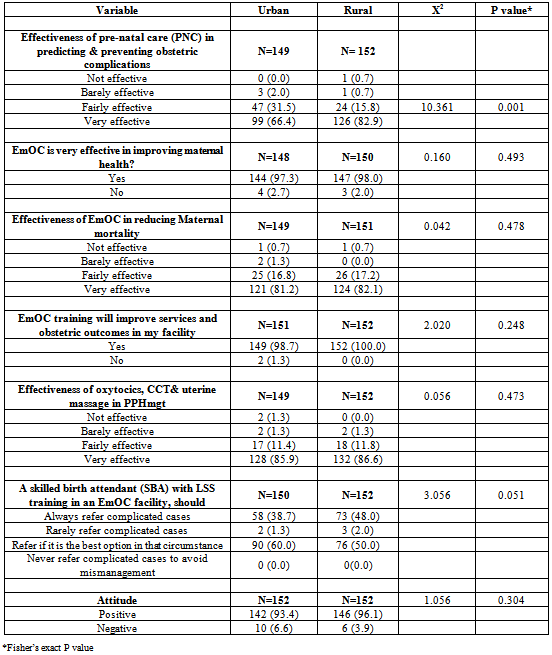

3.4. Respondents’ Attitude towards EmOC

- Majority of the respondents felt prenatal care is very effective in predicting and preventing obstetric complications and death. More rural, 126 (82.9%) compared to urban, 99 (66.4%) respondents think in this manner, (P= 0.001*).Almost all the respondents, 148 (97.3%) urban and 147 (98.0%) rural, felt EmOC is effective in improving maternal health. Similarly most respondents, 121 (81.2%) urban and 124 (82.1%) rural, felt EmOC is very effective in reducing maternal deaths.In addition, almost all the urban respondents, 149 (98.7%) and all the rural respondents, 152 (100.0%), felt training and re-fresher courses will improve EmOC service delivery in their facilities (Table 6).Administration of oxytocics, controlled cord traction and uterine massage were perceived as very effective techniques in the management of PPH secondary to atonic uterus; 126 (85.9%) urban and 132 (86.6%) rural respondents thought this to be very effective. More rural, 48.0% compared to 38.7% of urban respondents thought a skilled birth attendant with life saving skills training should always refer complicated cases to other centers (p=0.051). Majority of the respondents demonstrated positive attitude towards EmOC, only 10 (6.6%) urban and 6 (3.9%) rural respondents showed negative attitude towards EmOC (Table 6).

|

|

|

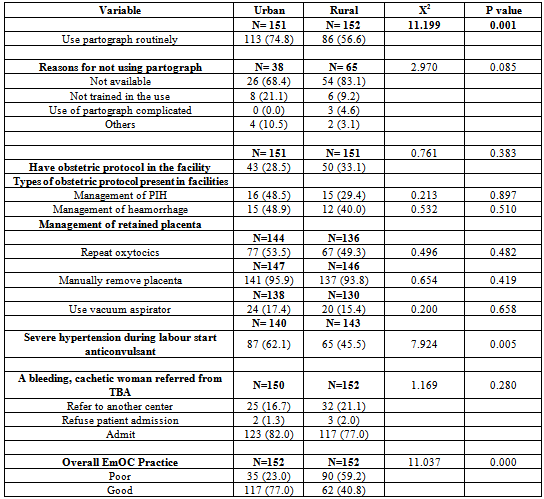

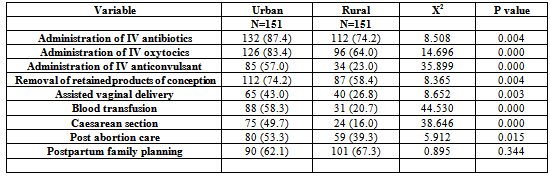

3.5. Respondents’ Practices of EmOC Services

- More urban, 113 (74.8%) compared to rural, 86 (56.6%) respondents reported routine use of partograph for active management of labour. This observed difference was statistically significant and indicated a positive association of use of partograph with urban setting (P=0.001).Reasons for non use of partographs among non-users in urban and rural areas respectively include, non-availability(68.4%) and (83.1%), not trained in its use (21.1% and 9.2%), use of partograph is complicated (0.0% and 4.6%) p=0.085).Only 43 (28.5%) urban and 50 (33.1%) rural respondents reported having obstetric protocols in their facilities (p = 0.383). The obstetric protocols frequently reported by respondents are protocols for the management of Pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH), urban (48.5%) and rural (29.4%); and protocol for the management of obstetric heamorrhage, urban (48.9%) and rural (40.0%). There is no statistically significant difference in these practices between urban and rural respondents (P = 0.897 and 0.510)Majority of the respondents in urban, 141 (95.9%) and rural, 137 (93.8%) will manually remove placenta in a case of retained placenta (p= 0.419).Approximately 8 out of 10 respondents(82.6%, urban, 84.6% rural), correctly identified that vacuum aspirator should not be used in the management of retained placenta (P = 0.658). More urban 87 (62.1%) compared to rural 65 (45.5) respondents will institute anticonvulsant therapy in a case of severe hypertension during labour. There is statistically significant difference in this practice between urban and rural respondents (p=0.005) Table 7.Majority of the respondents in both urban, 123 (82.0%) and rural, 117 (77.0%) areas will admit a mismanaged case of PPH from a TBA’s into their facilities (Table 7).Respondents’ reported practice of EmOC interventions, three months prior to this study revealed statistically significant differences in all eight interventions except in postpartum family planning, which more rural respondents reportedly practiced (Table 8).Overall, good practices of EmOC were reported in 117 (77%) urban and 62 (40.8%) rural respondents. More rural 90 (59.2%) respondents reported poor EmOC practice compared to 35 (23%) of urban respondents. There is a statistically significant difference (p=0.000) in the level of EmOC practice between urban and rural respondents (Table 7).

|

|

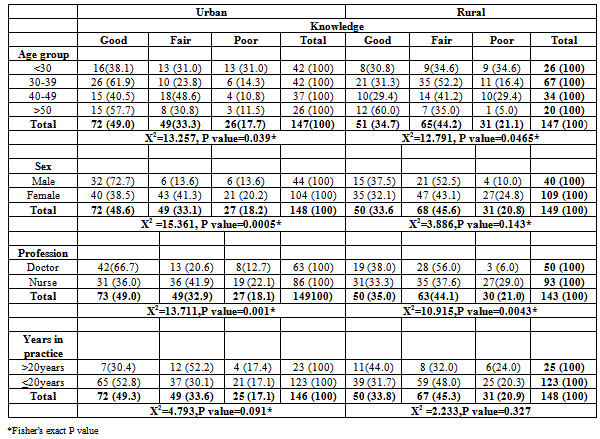

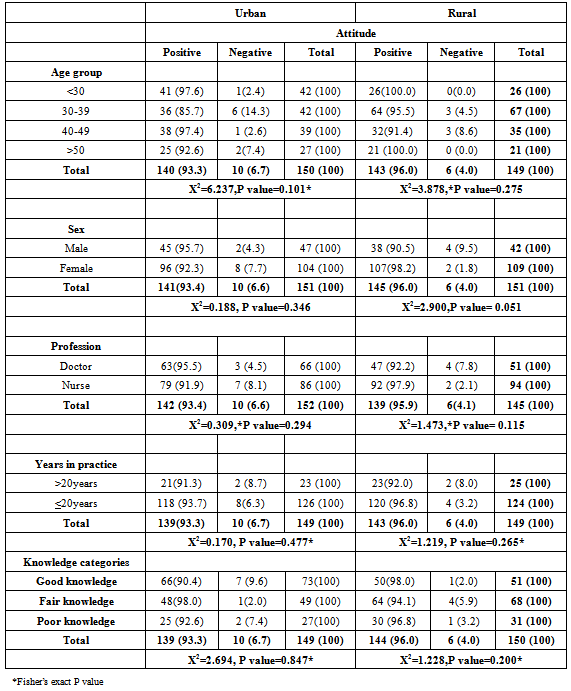

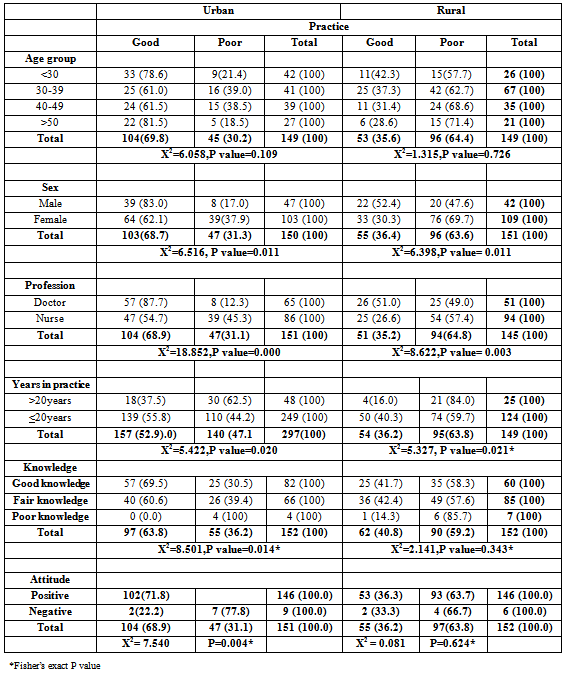

3.6. Association between the General Characteristics of Respondents and Their Level of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of EmOC

- Respondents’ age group was significantly associated with their level of knowledge in both urban (p = 0.039) and rural (p = 0.047) settings. Those within the age group 30 – 39 years were more likely to have better knowledge than those in other age groups. However, respondents’ gender was associated with knowledge of EmOC in only urban (p= 0.005) areas. Male respondents were more likely to have better knowledge than their female counterparts. Profession was also found to be associated with knowledge of EmOC in both urban (P = 0.001) and rural (P = 0.004) settings. Doctors were more likely to have better knowledge of EmOC than nurses. The length of years in practice did not significantly influence knowledge of EmOC among the respondents in the both areas (rural, p= 0.327, urban, p=0.091). However, those who had spent less than 20 years in practice were observed to have better knowledge than those who had been practicing longer.(Table 9)Respondents’ age was not significantly associated with their overall attitude in both urban (p = 0.101) and rural (p = 0.275) settings. Similar findings were also observed for association between gender (P=0.346[urban] p=0.051[rural]), profession (p=0.294[urban],p=0.115[rural]), years of practice (p= 0.477 [urban], p=0.265[rural]) and knowledge (p=0.847 [urban], P=0.200[rural] in both urban and rural areas respectively (Table 10).Of all the socio-demographics of respondents explored, the gender (urban, p=0.011, rural, p=0.011) professional category (urban, p=0.000, rural, p=0.003) and length of service (urban, p=0.020, rural, p=0.021) significantly influenced practice in the both areas. Males, doctors and those who were less than 20 years in practice were more likely to have better practice of EmOC than females, nurses and those who had spent more than 20 years in service. Knowledge (urban, p=0.014) and attitude (urban, p=0.004) towards EmOC services significantly influenced practice only in urban areas (Table 11). Using multiple logistic regression analysis, in the urban areas, factors that significantly influenced practice were attitude of respondents to EmOC (OR= 10.287, 95% CI= 1.839 – 57.554, p=0.008) and professional category of the respondents (OR= 0.175, 95% CI= 0.053 - 0.586, p=0.005). Those with positive attitude were about ten times more likely to have good practices of EmOc than those with negative attitude.Midwives/Nurses were 0.1 times less likely to have good practice of EmOC.In the rural areas, only professional category significantly influenced (OR=0.356, 95% CI=0.130 – 0.978, p=0.045) practice of EmOC. Midwives/Nurses were 0.3 times less likely to have good practice of EmOC than doctors.

|

|

|

3.7. Human Resources Distributionin Urban and RuralHealth Facilities

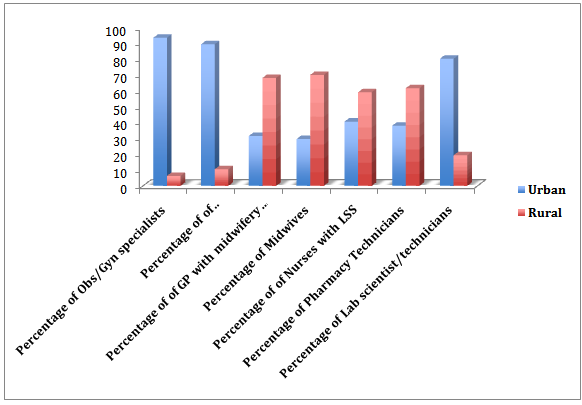

- Majority of the specialists (obstetricians/gynecologists) were located in the urban facilities, 93.8% compared to 6.3% in the rural facilities.Similarly, most of the anesthesiologists/anesthetic nurses are located in the four urban facilities, 89.7% compared to 10.5% in the nine rural facilities visited. The disparity in the availability of anesthesiologists/anesthetic nurse between urban and rural facilities was statistically significant (P = 0.048) with more availability in the urban compared to the rural facilities. For other categories of human resources, the proportion in urban as compared to rural areas respectively were: G.P with midwifery skills(31.6% and 68.4%); Midwives (29.7% and 70.3%); Nurses with LSS skills (40.7%and 59.3%); lab scientist/technicians (80.6% and 19.4%) (Fig.1).

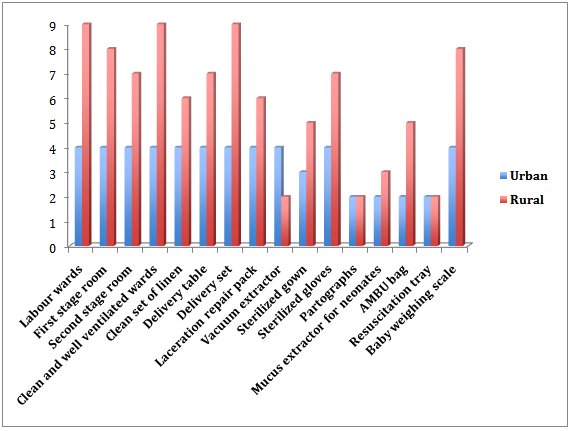

3.8. Distribution of Labour Ward Facilities in the Urban and Rural Health Facilities

- All the four urban facilities visited had vacuum extractor in their labour ward (100.0%). Only two out of nine rural facilities visited had vacuum extractor in their labour ward (22.3%). The difference in availability and distribution of vacuum extractor between urban and rural centers was statistically significant (P= 0.021) (Fig. 2).Oxygen cylinder was available in the labour wards of three out of four urban centers visited (75.0%). No facility in the rural centers had an oxygen cylinder in their labour wards.There is a statistically significant difference in the distribution availability of oxygen cylinder in the labour wards of urban compared to the rural facilities (p=0.014) (Fig.3)

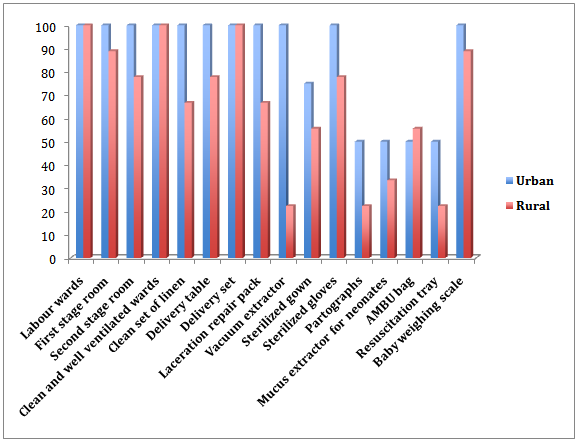

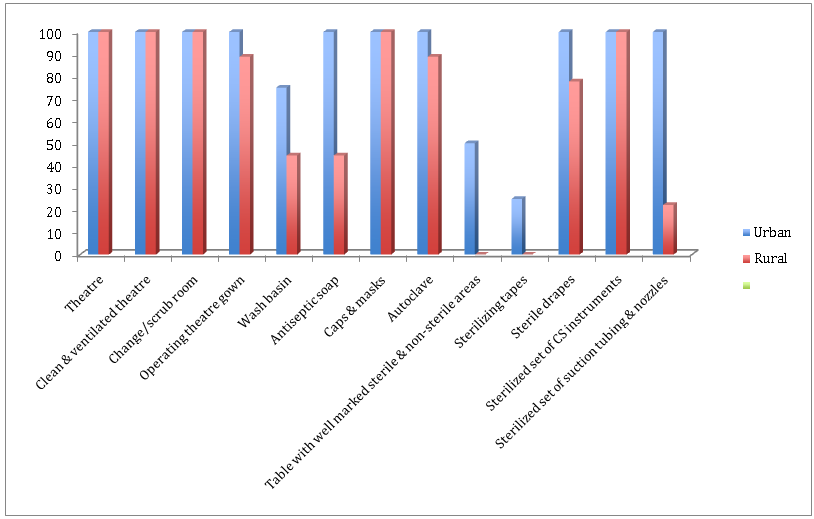

3.9. Distribution of Theatre Facilities in the Urban and Rural Health Facilities

- Sterilized sets of suction tubing and nozzles were available in the theatre of all four urban facilities visited. Only two out of nine facilities in the urban centers had suction tubing and nozzles (Fig. 4)The distribution of suction tube and nozzles varied significantly between the urban and rural facilities (p=0.021) indicating an association between availability of suction tubing and nozzle with location, more in urban compared to rural.Suction machine was available in the theatre of all the four urban facilities (100.0%) but only two out of nine rural facilities (22.3%) had suction machines in their theatre. (Fig. 5)The difference in the availability of suction machine between urban and rural facilities is statistically significant (P-value 0.021).Only two out of four facilities (50%) in the urban areas had blood bank, while none of the rural facilities had blood bank (Fig. 6).

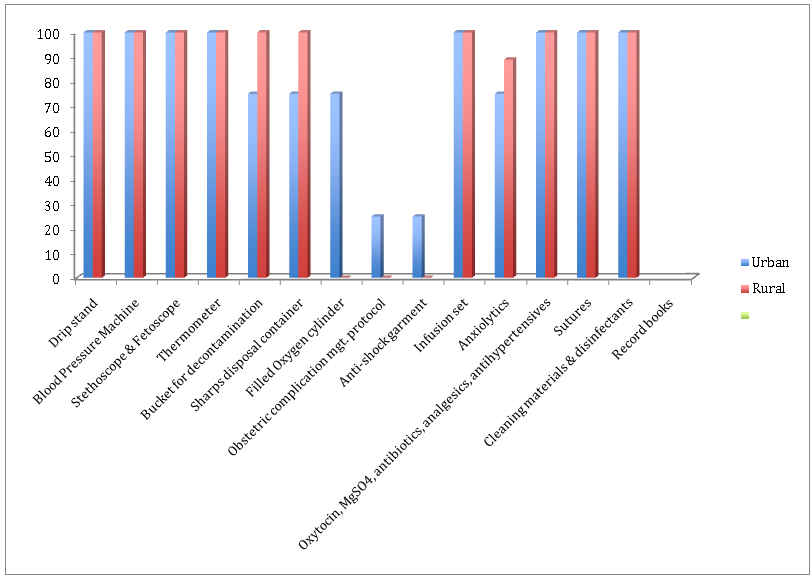

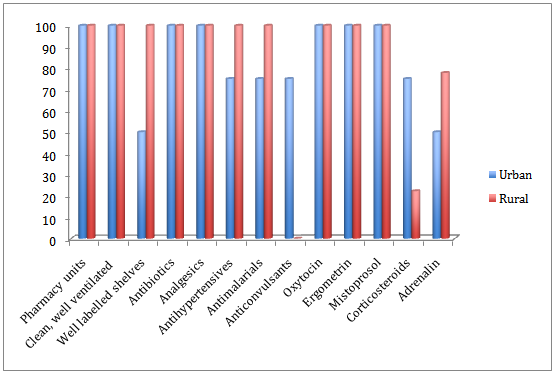

3.10. Distribution of PharmacyUnits in the Urban and Rural Health Facilities

- Three out of four urban facilities (75%) visited had anticonvulsant in their drug stock. No facility in the rural areas (0.0%) had anticonvulsant in their drug stock (Fig. 6). There is statistically significant association in the availability of anticonvulsant in the urban centers compared to the rural center (P = 0.018).

| Figure 1. Human Resources Distributionin Urban and Ruralhealth facilities |

| Figure 2. Distribution of labour ward facilities (per facility) in the urban and rural health facilities |

| Figure 3. Distribution of labour ward facilities (per facility) in the urban and rural health facilities (cntd) |

| Figure 4. Distribution of theatre facilities in the urban and rural health facilities |

| Figure 5. Distribution of theatre facilities in the urban and rural health facilities (cntd.) |

| Figure 6. Distribution of Pharmacyunit facilities in the urban and rural health facilities |

4. Discussion

- The quality of care and assistance women receive during pregnancy are predictors of the survival and health of mother and child. The continuing burden of maternal mortality, especially in developing countries has prompted increased agitation globally for life-saving obstetric practices such as EmOC. More respondents in the urban areas were better informed about EmOC than their rural counterparts. Knowledge level in the urban area compares with findings of studies done across four countries: Benin, Rwanda, Ecuador and Jamaica, where 55.8% 26 knowledge questions were answered correctly; this similarity in knowledge level may be due to the fact that these study areas, being urban, were more likely to have access to information and training opportunities than in the rural areas where such opportunities are limited. This finding is however different from that of a study done in south-west, Nigeria, where only 0.7% of respondents had good knowledge on EmOC.8 The disparity in knowledge may have been from the survey instrument used and the study population. This study used only health providers from secondary facilities and close-ended questions unlike the south-west study, where respondents in addition to doctors and nurses, included community health extension workers, and open ended questions were used. It is easier to see and recall what one knows than to imagine and recall. Surveys have shown that health indices, determinants of health and quality of care are higher in the south-west compared to other zones of the country.6, 11Knowledge is one of the determinants of competence and in this study, knowledge was statistically significantly (p=0.014) associated with practice in the urban settings. Current national survey puts the number of births attended by skill providers at 39%, whether these skilled providers possess the requisite competence to manage life-threatening emergencies, is a question only research can answer. 6, 27Similarly, the level of knowledge found in a study done across four countries: Benin, Rwanda, Jamaica, and Ecuador, is comparable to the level found in urban areas of this study. 26 The African countries performed below the average score compared to the South American and Caribbean countries. The level of knowledge reflects the quality of training (pre-placement, in-service and on the job) received by health providers in these areas. Policy makers often decry the high maternal mortality ratio but have not shown sufficient political will to make the necessary commitments to improve maternal health. 28Demonstrable gaps in health service delivery and health outcomes have been observed between urban and rural areas across West Africa, and higher levels of maternal mortality are recorded in rural areas. These gaps are not limited to West Africa; they are observed in other resource poor settings. 12, 30, 31 In this study, the knowledge gap between urban and rural setting was statistically significant (p=0.027). Urban areas typically have access to better equipment, supplies, training, and supervision than the rural areas. In this study, percent availability of specialists and higher cadre staff was higher in the urban areas. The presence of this cadre of staff enhances quality of service delivery, supervision, monitoring and transmission of knowledge from higher to lower cadre health officers. Antenatal risk assessment, (a cheap and easy tool, not requiring special skills), a well-advocated component of the safe motherhood initiative; was noted to be entrenched among respondents despite the “paradigm shift” to evidence based interventions, such as EmOC. 32 EmOC is one of the safe motherhood interventions that consider every pregnancy as having risk of developing complications. 33In this study, most respondents felt prenatal care is very effective in predicting and preventing obstetric complications, rather than perceiving every pregnancy as having potential to develop risks that could lead to complications and hence institute complications readiness strategies. This attitude is comparable to findings from a study done in South-West Nigeria.8 “Attitude is an unexpressed behavior (practice),” implying that respondents are more likely to practice what they feel is right rather than what has the stronger evidence of effectiveness 34thus having negative implications on efforts to reduce maternal mortality in these settings. Respondents who reported being trained on any life saving skill is 26.0% in urban areas and 36.6% in rural areas, much higher than the levels found in a study done in Osun and Ekiti states, where only 9% of respondents reported being trained on any LSS. 8 This disparity in findings between these studies may be due to the fact that CHEWs in addition to doctors and nurses comprised the study population of the Osun and Ekiti study unlike this study that comprised of only doctors and nurses, working at the secondary level of care. Life saving skills is acquired through training and practice to improve health providers’ technical competence for managing obstetric emergencies. Judging from the relatively low percentage of staff trained on obstetric life saving skills as seen in this study and other studies done across the country, achieving the MDG5 by 2015 may be difficult for the country. Routine use of partograph for monitoring of active phase of labour was reported higher in this study than levels reported from previous studies done in Nigeria and other part of the sub-region. 9, 26This high level is incongruent with findings from the facility observation using checklist, where only 2 (50%) facilities in the urban and 2 (22.3%) facilities in the rural areas had partograph in their facilities. Studies have shown that reported practice is much higher than structured observation for skill performance; this may be the reason for high levels observed in this study. 8, 26Inspite of the reporting, the level of use is still very low because every labour is supposed to be monitored with a partograph to aid detection and prompt decision making in the event of prolonged obstructed labour. This complication has been implicated in 11% of all direct obstetric deaths. 7, 35, 36 It therefore implies that a considerable percentage of this life –threatening complication is not detected early, thereby increasing the level of preventable deaths in these settings. 37,38 Availability of obstetric protocols and guidelines is low compared to the level reported in a survey done in New South Wales (NSW), where 94% of facilities that provided maternity services had protocols for the management of PPH and 71% of respondents from small rural and urban facilities have received PPH protocols. The reason for the high levels of available PPH protocol in NSW is the advanced health care system, the survey was carried out to monitor the implementation of the distribution of the new PPH protocol by the department of health to all facilities providing maternity services in the area.13 The low availability of obstetric protocols recorded in this study may likely be due to shortage in supply or management and policy problems. This situation has implications for quality of obstetric services provided, as lack of protocols will either mean that providers may not know what to do in a given situation or it may encourage practice that is solely dependent on provider’s intuition, which may lead to adverse health outcomes for clients. Administration of intravenous antibiotics and oxytocics are the most frequently reported signal functions of EmOC performed by maternity unit operatives.11, 39 This is comparable to the performance levels and availability reported in this study. Reporting of high levels of oxytocics and antibiotics are likely to reflect their use in general obstetric practices not just for obstetric emergencies. However, the use of these drugs for non-emergency purposes suggests their availability and potential use for true obstetric emergencies. This situation has good implications for EmOC and efforts at reducing maternal mortality as 11-17% direct obstetric deaths caused by sepsis will be prevented. 7, 34Generally, medical treatment signal functions are more frequently performed and available than the manual procedures. The least medical treatment reported is IV anticonvulsant (MgSO4). 11, 38 Similarly, low levels of performance of this signal function are recorded in this study. Relative infrequencies of occurrence of PIH may be a factor in explaining low reporting rate of this signal function. Assisted vaginal delivery may be the signal function that most frequently stimulates policy debate and perhaps controversy. It appears to be done less and less often in most countries throughout the world. 40It is highly dependent on equipment and training. Forceps require more training and experience than vacuum extraction and thus, vacuum extraction appears to be the instrument of choice in current international training programs. In some countries, particularly in Latin America, pre-service curricula for physicians or specialists no longer include assisted vaginal delivery. The abandonment of assisted delivery has probably contributed to the increasing cesarean delivery rates. Guidelines to non-usage of vacuum extraction in high HIV prevalence areas may lower its use even further. 41 The level of assisted vaginal deliveries reported in this study is not in keeping with other studies and incongruent with the level of availability of vacuum extractor or forceps recorded in this study.11, 16, 35, 38 The high levels of assisted vaginal delivery recorded in this study may be from over reporting of its use, some of the nurses interviewed actually reported attending to normal delivery as assisted vaginal delivery. Besides, the facility observation revealed no rural facility had a functioning vacuum extractor. This low level of assisted vaginal delivery may translate to increased caesarean delivery, increased workload for the staff skilled in the act and exceeding the recommended levels (maximum 15%) of caesarean delivery as a proportion of all births in the population.The composite score on overall EmOC practices recorded in this study is higher than findings in other studies. The possible reason for this discrepancy may be the self - reporting method used to assess practice in this study as against structured observation and skill performance assessment using anatomical models in other studies. 8, 26 The method used in assessing practice notwithstanding, the level of practice recorded in this study implies low performance, poor quality of care, inadequate health service delivery and consequently, insufficient progress towards reducing maternal mortality. Practice of EmOC was higher in urban setting; they possibly receive more frequent training, better supervision and monitoring since they have higher proportion of specialists and higher cadre staff.In health care sector and in maternal health particularly, human resources are recognized as indispensible to intervention efficiency, staff shortages are a major obstacle to providing quality obstetric care. 9, 14, 15, 42The World Health Report of 2005 stipulates the need for 4 doctors and 20 midwives for every 3,500 births and the 2006 report recommends a minimum of 2.28 professional care provider per 1,000 people to achieve 80% skilled attendance. 43, 44 In this study, shortage was seen not in number of staff but the right mix of manpower. Most of the specialists were concentrated in the urban areas as compared to the rural area, which is similar to findings in Bangladesh and other previous studies.27 Obstetric haemorrhage is implicated in 28% of direct obstetric deaths, severe bleeding after birth can kill a healthy woman within two hours if she is unattended.4Anaemia has been implicated as the cause of 11% of indirect obstetric deaths.7 Availability of blood for the treatment of severe anaemia in pregnancy, for surgeries (caesarean section and laparotomy), acute replacement in severe obstetric bleeding and other obstetric emergencies that require blood transfusion is one of the signal functions of EmOC. One of the least available resources in this study is blood and blood products; there were no blood banks in the nine rural facilities and only two urban facilities had blood banks. This finding is in keeping with a study done in Sagamu, Ogun state, south-west Nigeria, were lack of blood for transfusion was identified as one of the reasons for increased maternal death in the University teaching hospital.10 In Iraq only 26.5% (5/19) of facilities studied provided blood transfusion and in Uganda 91% of facilities expected to perform blood transfusion did not, due to lack of availability.35, 45Reasons for non-availability of blood may be due to the huge cost for running and maintaining a blood bank in rural areas where there is lack/inadequate power supply, shortage of laboratories and reagents which limits technicians’ ability to test and screen blood for transfusion, unavailability of donors especially in culturally sensitive settings and other systemic problems. Some of the care providers resorted in direct donation from patients’ spouses or relatives in surgery and other cases requiring blood transfusion. This situation portends grave implications for the attainment of the MDG5. Magnesium sulphate was another supply that was scarcely available in these facilities; no rural facility had this drug in their pharmacy as at the time of this study. This further explains the low use of IV anticonvulsant among rural respondents in the last three months prior to this study. One out of four (25%) urban facilities and no facility in the rural areas had anti-shock garment. This situation is not in keeping with the proportion observed in the PHCs with the Midwife Service Scheme (MSS) study, where 12% of the facilities had anti-shock garment for the management of shock. The PHCs with MSS should be comparable with the rural facilities in this study because of their rural location. Possible explanation for the better availability of anti-shock garment in the MSS may be because the scheme is a special – intervention national program aimed at improving rural human resource to ultimately improve access to skilled attendance at delivery. The hospital management board manages secondary facilities and procurement of materials and maintenance of existing ones is usually associated with “bottle necks” that hamper performance.Although, availability of the signal functions is based upon observation or review of records of actual practices at facility level, and not what the facility should theoretically be able to perform, in this study the observation of available resources was equated as potential for performance of the signal functions those resources were meant for. For instance, if the drugs for medical treatment, equipment for manual procedures, and care providers with the right skill, competence and motivations are available; then nothing should prevent the actual performance of the signal functions.Based on the adjusted criteria stated in this study, only two out of four (50%) of urban facilities met the criteria for comprehensive emergency obstetric care compared to none (0.0%) in the rural areas qualifying as a comprehensive emergency obstetric care facility, due to non-availability of blood bank or concrete arrangement for regular supply of blood and blood products, and magnesium sulphate for PIH.The findings in this study, where most of the facilities performed less than the expected number of signal functions are in keeping with results found in studies done in Afghanistan, where 42% of peripheral facilities did not perform all nine signal functions, Iraq, only 26.3% (5/19) of the facilities provided all 8 comprehensive emergency signal functions, and also in other parts of the world including the United States of America.44, 46, 47 Assessment of EmOC is a means of monitoring progress toward achieving the millennium development goals 4 and 5 at the facility level. Findings from this study revealed that effective implementation of the EmOC strategy in Rivers state is yet to be fully operational with challenges of inadequately trained health manpower and inadequate or lack or resources to provide EmOC services, with facilities in the rural areas being more disadvantaged. This situation puts the progress made towards reducing maternal mortality and attainment of these MDGs in the state in jeopardy.

5. Conclusions

- Knowledge of EmOC among health care providers at the secondary level of care in Rivers state is still suboptimal. More urban (28.9%) than rural (16.4%) respondents had good knowledge of the EmOC concept, this knowledge gap is statistically significant (p=0.027). Findings also revealed an entrenchment of the old practice of antenatal risk assessment as predictors of obstetric complications in both groups; however, this was more noticeable among the rural respondents.The practice of emergency obstetric care was found to be relatively better among urban respondents, 77% compared to respondents in rural facilities 40.8%; however, the levels in both settings are grossly inadequate for obstetric emergency services. Knowledge (p= 0.014) and attitude (p=0.004) were significantly associated with practice among the urban respondents but not among the rural respondents where there was no observable association (knowledge, p = 0.343; attitude, p=0.624).Availability and distribution of resources were found to be better, although not adequate, in the urban facilities compared to the rural facilities; especially in human resources where the rural facilities lacked specialists and higher cadre staff. These inadequacies in resources may have contributed to the lower knowledge and poorer practice observed among the rural respondents.

6. Recommendations

- Provision of “On the job” and in-service trainings on emergency obstetric care to improve knowledge and skills of health workers on EmOC is recommended. Regular training, re-training and refresher courses on EmOC should be organized by the state ministry of health, other government and non-governmental agencies. Supervision and monitoring of lower cadre staff by higher cadre staff to ensure quality service delivery. Teachings and practice of EmOC to be included in pre-qualification trainings for nursing /midwifery and medical institutions.Deployment and retention of the right mix of qualified staff to rural areas to improve service delivery. State government should make provision for incentives and special allowances for health workers in rural facilities.There should be equitable and even distribution of skilled staff among and between rural and urban facilities. The ministry of health should develop obstetric guidelines and distribute to all maternity units. Institution of government policy and effective implementation of a statewide blood bank system to improve availability and access by all facilities. The central drug store should improve the stocking and adequate distribution of intravenous anticonvulsants and other drugs and materials required for emergency obstetric care.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML