-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics

p-ISSN: 2163-1433 e-ISSN: 2163-1441

2013; 3(2): 18-28

doi:10.5923/j.cmd.20130302.02

Prevalence and Risk Factors of Diabetes in Adult Population of South Asia

Zaheer A Kakar1, 2, Muhammad A Siddiqui3, Rooh Al Amin4

1Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH), Department of Public Health, Quetta, Pakistan

2Department of Public Health, University of East London, UK

3School of Health Sciences, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, UK

4School of Health and Wellbeing, University of Wolverhampton, UK

Correspondence to: Muhammad A Siddiqui, School of Health Sciences, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, UK.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Diabetes has been one of the most studied medical predicaments in recent times. Unfortunately, the lack of basic health services and paucity of resources are observed as biggest challenges to hold back this epidemic in the region of South Asia. The objective of this review is to examine the prevalence and risk factors of diabetes in adult population of South Asia. The units of analysis included in this review reported that the prevalence of diabetes ranged from 0.9% in Bangladesh to 21.2% in India. The highest prevalence was observed in urban areas showing rapid urbanization, which plays major role for the increased prevalence. However, the results also indicate that the prevalence of diabetes is on the rise even in rural areas. Although, not a single determinant is responsible for the high prevalence, a complex interaction of different factors plays a part for the increased prevalence of diabetes in South Asia.

Keywords: Diabetes, Prevalence, Risk Factors, Epidemiology, South Asia

Cite this paper: Zaheer A Kakar, Muhammad A Siddiqui, Rooh Al Amin, Prevalence and Risk Factors of Diabetes in Adult Population of South Asia, Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 18-28. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20130302.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is a threat for all world populations and it is a lurking dilemma for global heath1. The global burden of diabetes is increasing every year and there is every indication that this trend will continue into the near future2. In 1985, there were over 30 million diagnosed cases of diabetes and its prevalence has increased to 171 million cases in 20003. It is estimated that by the year 2030 the prevalence of diabetes will reach to 366 million cases and the mortality rate of sufferers will be doubled4. Currently, the mortality rate of diabetes patients is on the rise and each year an estimated 3.2 million people lose their lives prematurely due to complications from the disease5. The population affected by diabetes is mostly between ages of 35 and 60 year old2. It is evident from other studies which have been conducted worldwide that new cases of diabetes are increasing due to a variety reasons6,7. For instance, urbanisation, obesity, population growth, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and, most importantly, the lacks of a healthy life style are the classic examples given for the increase in the instance of diabetes8. Eventually, these factors are contributing to the increase in the number of diabetic people in developing countries, most significantly in the region of South Asia9.Surveys conducted worldwide on the prevalence of diabetes indicate that substantial variation has been seen, ranging from 0% in Papua New Guinea to 26% among the residents of Pacific islands7. In the year 2002, disability adjusted life years (DALY’s) was 1.1% of the total disease burden and seen in Southeast Asia, which includes Bangladesh andits intensity varies worldwide4.The highest burden was India, with 3.6 million of DALY’s lost, and 1.3 million in China10. Currently, 246 million people are known to have diabetes and it is estimated that global figures will reach 380 million by 20304. It is projected that by 2030, India will lead the world at 79.4 million people with diabetes following by China with 42.3 million and USA with 30.3 million2.The majority of people in the developing countries are within the age range of 45 to 65 years, in contrast to the developed world whose ages range from 64 to 70 years and this will increase by 2030, with 50 million people with diabetes in the developed world and 85 million in developing countries11.In the UK alone, around 2.35 million people are affected by diabetes12. A study in UK for Type 2 diabetes in various communities had shown that people from South East Asia are more vulnerable to the disease as compared to other residents5. Currently, immigrants from South Asia in the UK are more likely to be diabetic, around six times more likely than white European. These numbers are expected to increase by 47% by 202513. It is predicted that more than half a million of these people may have diabetes without knowing the consequences of it13.According to the WHO4, as compared to the developed world, developing countries have a bigger burden of diabetes. Due to low public awareness of diabetes in developing countries, it is certain that they will face the impact of diabetes waves in coming years15. More than 95% of the people suffer from diabetes in South Asia have Type 2 diabetes16. Since it is evident that Type 2 diabetes is an adulthood condition, rural to urban population shift increases its prevalence17. Wide variation is seen in India where urban prevalence of Type 2 diabetes is 12.1% compared to rural areas which is 2.9%18. In Pakistan the urban prevalence of Type 2 diabetes is 10.8% and rural prevalence is 6.5%17. It is predicted that by 2030 the number of affected people will reach to 46 million in India, 14 million in Pakistan and 11.1 million in Bangladesh2. Annually, 3.8 million peoples lose their lives due to diabetic complications, which is almost equivalent to loss of life associated with HIV/AIDS19. Rapid urbanisation is a major risk factor associated with diabetes in Bangladesh where the prevalence of diabetes is low in rural areas at 4% while in the urban area it is 8%20. The aim of this review was to investigate prevalence of diabetes in the adult population living in South Asian countries and to examine the risk factors associated with diabetes amongst the population aged 20–65 years living in South Asia.

2. Method

- A search was carried out on electronic databases to identify eligible studies which were relevant to this review. Pub Med, Cochrane, Science Direct and High wire were used to collect data and obtain research papers. A supplementary search was also done in order to fill the gaps. Indian and Pakistani journal were manually searched to retrieve regional papers. References from the primary search were manually searched to obtain the intended papers. The keywords included in the search strategy were prevalence, risk factors, epidemiology, diabetes and prevalence of diabetes in South Asia. According to Sim and Wright21, inclusion and exclusion criteria should not be established retrospectively, in the light of accruing findings. The criteria used to identify the papers to be included as units for analysis (papers selected for this literature review) were consist with regards to the following parameters.

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- 1. Publications (studies) reporting prevalence of diabetes. This is the main aim of the literature review.2. Risk factors associated with diabetes.3. The study was conducted in South Asia as this is the prime location of interest to examine the prevalence of diabetes.4. The studies from 1993 to 2008 were included as it is evident that a remarkable rise in prevalence of diabetes has been seen in last 15 years.5. The studies reporting the primary research were included. The purpose of these criteria is that primary research is the only source of data applicable for the purpose of this literature review.6. Studies reporting main outcomes (prevalence) conducted in both clinical and non-clinical settings. The aim of the review is to examine the prevalence of diabetes and its associated risk factors in the population belonging to any setting in these countries.7. Quantitative studies reporting prevalence and risk factors or both. Prevalence and risk factors can be reported if the quantitative data regarding these two variables are available.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- 1. Publications in languages other than English were excluded.2. Studies reporting the prevalence of diabetes in children were excluded.3. Qualitative studies were also excluded. To find prevalence, quantitative data is needed to address main research question of this review.4. Editorial and opinion letters were excluded.

3. Result

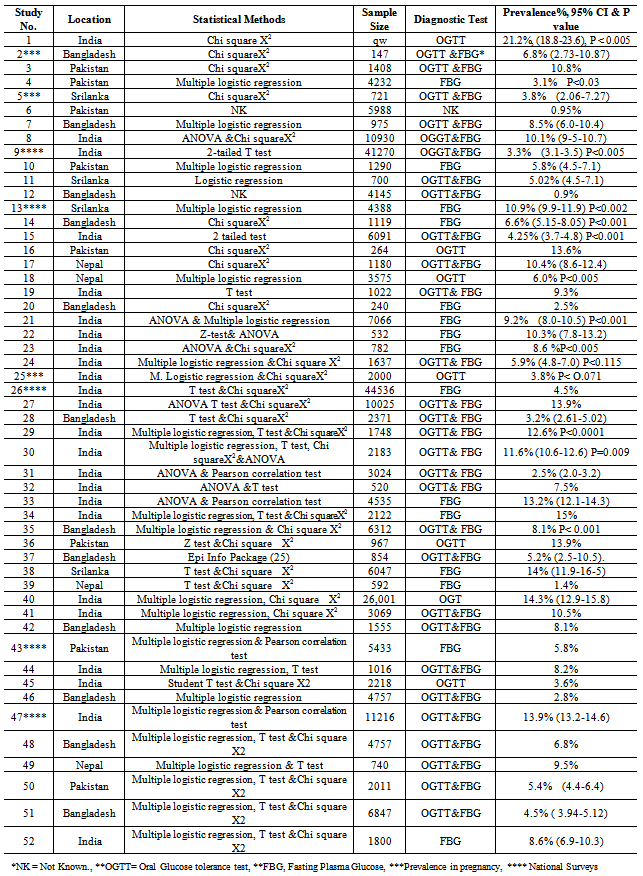

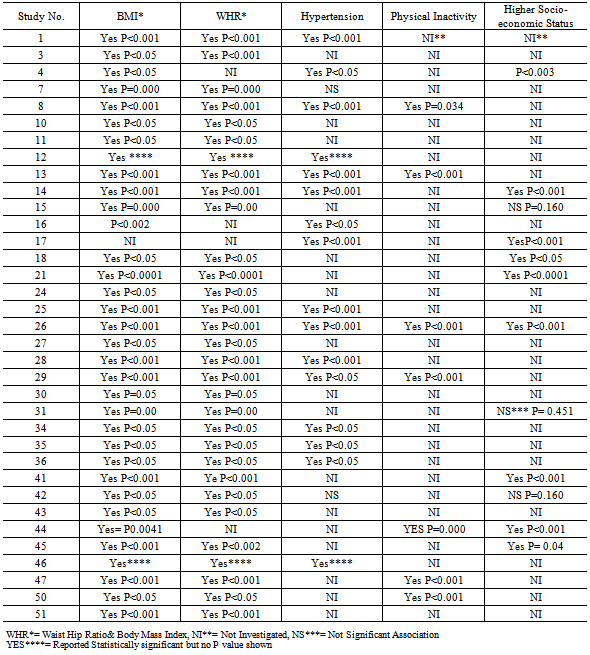

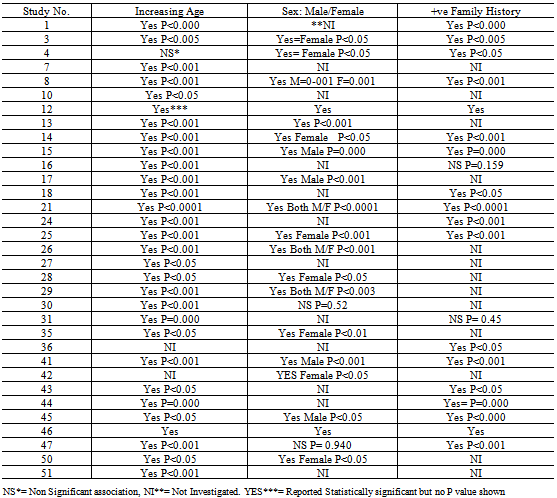

- Various search strategies were performed which yielded 542 papers in total.After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 52 original articles (Table 1) out of 542 were selected for the review.Overall, the prevalence of diabetes varies largely in urban and rural population across South Asia. The prevalence of diabetes in both the rural and urban population is reported in 9 studies. The national level survey conducted by Katulandaet al.22in Sri Lanka, reported a prevalence of 16.40% in the urban population. In contrast, a prevalence of 8.70% was reported in the rural population. This indicates that the fast pace of urbanization and an aging populace in Sri Lanka. There were 35 studies which examined the risk factors associated with diabetes. The main risk factor associated with diabetes (Table 2) reported in the studieswas obesity which includes Body Mass Index (BMI) and Waist/Hip Ratio (WHR). Besides this factor, identified risks also included increasing age, hypertension, positive family history, gender, low physical activity and higher socioeconomic class (Table 3). Unconventional risk factors were also found by Sayeedet al.23 and Zargar et al.24 among pregnant women. In gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) short height, a history of abortion and neonatal death were prominent risk factors. Increasing age was also reported in 28 studies. Higher socioeconomic class has been reported as a risk factor for diabetes in 9 studies. Hypertension was also distinguished as a major risk factor in 15 studies. Two studies25,26 stated a non-significant association ofhypertension with diabetes. In pregnant women, as reported in study 25, hypertension, BMI and WHR were also risks associated with diabetes. With regards to non-modifiable risk factors, increasing age was identified as a major risk factor.

|

4. Discussion

- Diabetes epidemic is still an enigma in South Asia. This review shows prevalence finding which range from 0.9% to 21.2% in Bangladesh and India respectively. The findings further advocate the steep rise of diabetes which is in accordance with WHO estimation for the year 20302. This fast rise further specifies that diabetes impact will be felt in South Asia more than any other part of the world. Almost identical prevalence 25.2% was found in cross sectional population based study in the ethnic migrants from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh in Netherlands39. Surprisingly, few studies like those included in this review were able to identify risk factors and prevalence of diabetes in different South Asian countries. The comparison of such studies is of utmost importance to understand the genetic and environmental factors which may contribute the increase of prevalence of diabetes within these countries. Most of the studies worldwide compare the risk factors of diabetes between Asian and European countries40. The review found different risk factors like obesity, physical inactivity, higher socioeconomic status, increased age, hypertension and positive family history. The high prevalence in urban as compared to rural areas was also identified in this literature review. Higher BMI and WHR were recognized as the independent risk factors for diabetes. Most of the risk factors found in the present study were almost same as reported in the community based study in India41. Apart from these conventional risk factors, smoking, short height and literacy were also identified as risk factors.The shifts of people from villages to cities for better life and such migrations especially in the developing countries are the root cause of increased prevalence. Numerous studies22,27,36,42,43 show high prevalence of diabetes in most urbanised cities of South Asia which indicates that urbanisation is playing key role in the increased prevalence. Kumar et al. reported 8.2% prevalence of diabetes in Ghwathior, the Indian city which is almost similar to many studies conducted in urban India44. The life style and nutrition profile is different in rural area as compared to urban. The inhabitants of South Asian countries who reside in rural areas are related to agriculture and mostly involved in intense physical work. The sudden change in activity and diet profile often drag them to develop weight. Oily and saturated fat and less use of fibre as they used to take in their villages might also explain this rise as diet/nutrition play important role to develop obesity and diabetes. The low physical activity, higher intake of fat, the rapid industrialisation and more importantly lack of healthy and recreational activities in the urban cities collectively trigger the mechanism of sedentary life style. This deskbound way of life combine with other environmental and genetic factors ultimately lead to obesity45. The majority of epidemiological studies conducted in the past in South Asia are in the context of cardiac diseases and different type of cancers46. So it is imperative to understand the determinants of nutritional behaviour in South Asian population.Bodullaet al.47 reported high prevalence (21.2%) of diabetes in affluent Indians. The physical activity has important impact on the prevalence of obesity. It is noticed that the people in high socio economic class and sedentary life style are more prone to develop diabetes. Physical inactivity increases the occurrence of diabetes. Contrary to this, the absence of obesity and more physical activity is related to low prevalence of diabetes, 0.95% in the study of Danish et al.48 in Pakistani Kashmir. The labour intensive life style showed increased physical activity and decreased incidence of diabetes as is evident from migrant labour of Chinese and African population in Malaysia49. Recent study conducted in the UK also highlighted that the Asian migrants are at high risks of diabetes because of their high percentage of sedentary life style50. This may be true for most of the South Asian population7. Life style modification is of vital importance to control diabetes. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme (IDPP) shows that metformin and life style modification both have similar effect to decrease the progression of diabetes51. A Substantiate reduction of risks 58% has also seen in UK, by the combination of metformin and life style interventions52. Unfortunately, little action has been taken to decrease the risk of this disease in South Asian countries. The effective intervention programmes tailored for each country might help to invert this trend of increasing diabetes. The “Diabetes Prevention Programme” (DPP) gives some indications that preventive measures and early life style modification might delay the onset of diabetes53. The findings of this review also suggest that intervention like lifestyle modification as an early tool is not in the hands of individuals to prevent this disease. It is here that the government’s role and their policy making becomes Among the South Asia countries, health intervention programmes currently exist only in Pakistan and India51. Unfortunately, the rest of South Asian countries still lack these facilities. Educational and life style modifications programmes have been proven to be important in controlling further progression of this disease, even in remote areas of India54. The population based intervention care programmes in India and Pakistan has witnessed significant influence in reducing obesity as well as diabetes7.Genetic factors are also strongly associated with central obesity. A study conducted in India has highlighted that even at low threshold of waist circumference; South Asians are at increased risk of glucose intolerance than white European55. Worryingly, having the same body weight the South Asians have more adiposity then European and residents of other part of the world56. According to Basit and Shera57 South Asian may have inherited gene, which promote accumulation of extra fat around the stomach and increase the risk of diabetes. The review findings also show that there is relationship between obesity and occurrence of diabetes in both urban and rural areas which may indicates genetic susceptibility in South Asian population22,27,36,58-61. This genetic susceptibility was also found in the migrants of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Sri Lankan Population in the UK62 and USA63. It is believed that environmental factors have eventually resulted in genetic modification and predisposition to diabetes. Diamond64 observed that the prevalence of DM is high in South Asian population whereas prevalence of DM is low in white population because they have not been exposed to the DM epidemic. Gerstein and Waltman65 further elaborated this observation and indicated gene-environmental factor as a critical factor in DM epidemiology. They concluded that the white population has low prevalence of DM because they have not been exposed to famine or mal-nutrition episodes for the last fifteen to twenty years. Resultantly, the white population had genetically adapted themselves to low insulin resistance and high calorie intakes. On the contrary, South Asian population have high insulin resistance because they have been exposed to famine and mal-nutrition episodes. Resultantly, the South Asian population did not get enough time to get them genetically adapted in fact they adapted themselves to new diabetogenic environment. In addition, Gerstein and Waltman65 also concluded that South Asian population develop DM if they are exposed to obesogenic environment.The high prevalence 6.8% of diabetes in pregnancy in Bangladesh23 and 3.8% in India24 is higher than the other study conducted in Africa66. Moreover, low birth weight and malnutrition at early life may contribute to develop this abnormality later in life. The scarcity of basic health facilities and social bias due to cultural as well as religious constraints all most equally exists in all South Asian countries. Some population groups have less access to the health care facilities. The female population is particularly comes in this disadvantaged group. Social and religious constraints do not allow them to avail medical and recreational facilities independently. They are completely dependent upon male household in this regard. There is no set antenatal programme in place in any South Asian country. This is why the early screening for GDM is not available which results in poor early prevention of this disease67. This circumstantial position may have caused increased incidence of diabetes in females particularly who are pregnant. The review also shows the higher rate of disease in various studies where females were included in the sample23.It may be concluded from the present study that a single determinant is not responsible for occurrence and higher prevalence for this disease. It is the complex interaction of multiple factors like obesity, physical inactivity, and inequality in socioeconomic position, familial aggregation and environmental influences which might be the reason for this epidemic. A single risk factor may be seen as behaving in contrast manner. For example, the study59 which was conducted in the slums of Northern India show high prevalence of 10.3% (CI= 7.8-13.2) and a study26 in Bangladesh with prevalence of 8.2%. These studies indicates that frequency is high in lower socio economic strata are even at risk of developing diabetes. It indicates epidemiological transition due to economic deprivation might play a vital role even in the low income groups.

5. Conclusions

- The severity of diabetes is and its spread in South Asia is on a rapid rise which needs to be intercepted. The limited resources, rapid population growth, ill knowledge of aetiology and its consequences have further deteriorated this epidemic. Exceptional growth of the disease and its complication are major blow to the national resources and manpower. A comprehensive strategy and intervention are needed to treat the disease and more importantly to prevent it.

6. Recommendations

- The following measures may be recommended to reduce the alarming prevalence of this disease in the light of this review.a. Individual as well as collective efforts by Governments, Public Health Services and Non-Governmental Organizations/Charities should be promoted to make the awareness of disease and its complication among the masses.b. A comprehensive strategy and programme should be in place to diagnose the disease and its prevention at an early stage.c. Specialized health care teams should be formulated to identify the population at risks.d. Public health measures should be taken in account for awareness and promotion of healthy diet.e. Reasonable funds should be allocated to provide recreational facilities which promote physical activity for the reduction of obesity, as this is one of the core causes of the disease.f. Micro level initiatives should be focusing the individuals first, then more broad approach to involve family, community and finally expand it to country level.g. An integrated screening programme is proposed to control the disease at an early stage, particularly in pregnant women, who are more vulnerable.h. A health care programme budgeting should be established for one step diabetic clinics for easy and early access to the potential diabetic patients.i. Long term research programme is needed to be targeted for developing evidence base strategy to modify the risk factors.j. The current progress in developed countries should be adopted as a story of achievement to curtail this epidemic.

7. Limitations of Study

- Like any other systematic literature review, this review also faces a series of limits. Despite numerous searching criteria by using the key words no papers was found in Maldives, Nepal and Afghanistan. The lack of data in these three South Asian countries also put doubts on the generalizability of the study, many of the factors which might have contributed to the strong rise and prevalence of the disease might have still been unavailable for research. The selection bias of sample size in few studies is also one of the limitations of the review. A level of heterogeneity and publication bias existed in this review, due to different sample sizes of studies. Differences in sample size can limit the internal validity of review. Majority of the studies were sporadic surveys which normally fail to provide the evidence between cause and effect. Apart from all these limitation the authors still believe that this review paved the way for further research in the South Asian population.

|

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML