-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Composite Materials

p-ISSN: 2166-479X e-ISSN: 2166-4919

2025; 15(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.cmaterials.20251501.01

Received: Dec. 15, 2024; Accepted: Jan. 12, 2025; Published: Jan. 21, 2025

Influence of the Alkaline Treatment of Eucalyptus Fibres on the Mechanical Behaviour of Low-Density Polyethylene Composites

Komlavi Henri-Séraphin N’Tsule 1, 2, 3, 4, Demagna Koffi 1, Kwamivi Nyonuwosro Segbeaya 4, Guyh Dituba Ngoma 5

1Innovations Institute in Ecomaterials, Ecoproduits and Ecoenergy (I2E3), Université de Québec a Trois-Rivieres (UQTR), Trois-Rivieres, Canada

2Surface Modification and analysis Laboratory, Université de Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR), Trois-Rivières, Canada

3Laboratory of Waste Treatment and Recovery Management (GTVD), Université de Lomé (UL), Togo

4Organic Chemistry Water Sciences and Environmental Laboratory (LaCOSEE), Université de Kara (UK), Togo

5Engineering Laboratory, Université de Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT), Rouyn-Noranda, Canada

Correspondence to: Komlavi Henri-Séraphin N’Tsule , Innovations Institute in Ecomaterials, Ecoproduits and Ecoenergy (I2E3), Université de Québec a Trois-Rivieres (UQTR), Trois-Rivieres, Canada.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The use of plant fibers in the formulation of polymer matrix composites requires prior treatment of the fibers. This treatment can be chemical, mechanical or the use of a coupling agent (usually copolymers). In the present study, the aim is to chemically treat the fibers. This involves treatment with 6% (w/v) sodium hydroxide. One of the aims of this study is to examine the influence of this treatment on the maximum loadings of the LDPE/eucalyptus fiber (EF) material. The LDPE matrix is readily available as virgin or recyclable waste, its low melting point between 105°C and 115°C makes it suitable for handling over a reasonable temperature range, and its mechanical strength holds up well before dropping between 75°C and 90°C. At the end of its useful life, this polymer is generally abandoned and becomes a source of environmental pollution, requiring recycling. All these advantages motivated the choice of LDPE in this study, the second aim of which is to produce environmentally friendly pavers. This choice also helps to reduce the pollution associated with LDPE polymers. The availability, fast growth, low density, and low cost of eucalyptus motivated the choice of eucalyptus species. 0%, 15% and 25% treated and untreated short fiber were used to formulate the composites. However, treated fiber-reinforced composites showed an improvement in ultimate tensile strength over untreated fiber composites. Microscopic (SEM-EDX) and FTIR-ATR analyses were carried out on the composites to determine their topology, as well as on the treated and untreated fibers to determine the change in functional groups after treatment. Fiber roughness is improved after treatment with NaOH.

Keywords: Eucalyptus fibers, Alkaline treatment, Mechanical properties

Cite this paper: Komlavi Henri-Séraphin N’Tsule , Demagna Koffi , Kwamivi Nyonuwosro Segbeaya , Guyh Dituba Ngoma , Influence of the Alkaline Treatment of Eucalyptus Fibres on the Mechanical Behaviour of Low-Density Polyethylene Composites, International Journal of Composite Materials, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.cmaterials.20251501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Eucalyptus fibers have been the subject of several reports [1], and their use in the formulation of composite materials has become an unprecedented reality [1] [2] [3], including characteristics such as morphology, anatomy and chemical structure, for both pulp and paper derivatives [4]. Thus, several species have been used in pulp and paper, but because of their high density and the possibility of making high-yield kraft pulps and fiber quality for excellent paper, Eucalyptus globulus has proved the best [5]. Despite this, other species, such as Eucalyptus nitens and hybrids of Eucalyptus globulus and Eucalyptus nitens, are used in pulp and paper. The ordered arrangement of molecules in a fibrous structure favors better reactivity with other substances. Indeed, in natural fibers, the amorphous part generally characterized by the presence of lignin, hemicellulose and pectin does not favor better adhesion between the components of a composite. To achieve this, it is necessary to clean this amorphous part to increase the degree of crystallinity of these fibers. To achieve this, existing methodological approaches are used. These methods include chemical treatment. These include mercerization, acetylation, silane treatment and potassium permanganate treatment. The chemical approach seems to be the most effective, as it allows us to control the concentration of chemical agents, treatment factors such as temperature and treatment time. For mercerization, it is the ionization reaction of the hydroxyl groups in the fibers that is brought into play by NaOH. Indeed, the NaOH concentration required for fiber treatment to avoid fiber degradation is judiciously chosen. For example, coir fibers treated with 3% w/v NaOH for 5 hours lost tensile strength, tensile modulus, and elongation at break [6]. It can be said that deterioration within the microfibrils has occurred, with the creation of pores and discontinuity phenomena along the same microfibril. Moreover, treating flax fibers with 2.5%, 5%, 7.5%, 10% and 15% w/v NaOH enabled Abral and al. [6] to find improved tensile and flexural strength in flax-polyester composites reinforced with fibers treated at 5% and 7.5%. Huda and al. [7], treated pineapple fibers for 2h at room temperature with 5% w/v NaOH. The authors found that the impact strength of the composite was 79% higher than that of untreated fibers. Also, Hashim and al. [8] treated kenaf fibers at different concentrations 2%, 6% and 10% w/v, for 30 min, 240 min and 480 min at 27°C, 60°C and 100°C and found a slight increase in the density of treated kenaf fibers compared to untreated ones. The same authors also observed a decrease in treated fiber diameter. In fact, if the mechanical properties of composites are improved after fiber reinforcement treatments, it’s not just a question of attributing this to one or two factors. As the dimensional non-stability of fibers is always in question, the factors that condition good mechanical properties of natural fiber-reinforced composites are dependent. These factors include fiber surface roughness, with adhesion dependent on the chemical nature of the fiber surface; fiber size; crystal structure and fiber morphology. Although many other factors can interfere with good interfacial adhesion. Various silane derivatives have been widely used in fiber treatment. Kushwaha and al. [9] pretreated bamboo fibers with 5% NaOH followed or not by treatment with different silane derivatives of 0.5%, 0.033%, 1% under various temperature and time conditions. Flexural strengths of 165.77 MPa and 149.00 MPa, respectively, were found for epoxy composites with Bamboo fibers treated with NaOH-Silane and with NaOH alone. Other works in the literature propose that the mercerization reaction is a process of cleaning fats, impurities and that no chemical reaction takes place between the elements of NaOH and the hydroxide groups of cellulose, hemicellulose. This confirms the idea of transition from native cellulose to cellulose.

| Figure 1. Mercerization reaction of the lignocellulosic substrate [10] |

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Materials

- NaOH (98%, buy from COACE CHEMICAL), was used for fiber treatment. The SEM, FTIR-ATR, Intron, ZHAFIR Plastics Machinery injection press (100-ton Zerus 900 press, Ebermannsdorf, Bavaria Germany) are used as formulation testing instruments for composites. Eucalyptus camaldulensis fibers are produced at the Innofibre at UQTR’s I2E3. Low-density polyethylene is purchased from COACE chemistry. In this study, the use of eucalyptus fibers is made. These are short fibers of 0.5 mm length and whose density is 0.68 g.cm-3 and 0.74 g.cm-3 respectively for the treated and untreated fibers.

|

2.2. Methods

- The eucalyptus wood was sampled in the Republic of Togo in the form of logs. the grinding of these logs in different granulometry was done at the Thermobium of innofibre at the Innovations Institute in Ecomaterials, Ecoproducts and Ecoenergy (I2E3) of the Université de Québec à trois-rivières (UQTR). The composite was formulated on two Thermotron-C.W. Brabender rollers (Model T303). This formulation is the same as that used by Gu and al. [21] [22] and Mijiyawa and al. [23] with changes in temperature and pressure.

| Figure 2. A- Thermotron-C.W. Brabender rollers (Model T303), B-Composite paste, C- ZERES ZE900 injection press |

| Figure 3. Composite formulation and specimen injection moulding stage |

|

2.2.1. Charpy Impact

- This test was performed on the Instron CEAST 9050 pendulum machine. It is equipped with a 5.4J hammer designed to determine the ductility or fragility of materials for breaking energy not exceeding 85% of the capacity of the material used according to ASTM D 6110-18. The specimens are cut in a V shape and the operations were carried out at 27°C.

2.2.2. Tensile and Flexural Tests

- The Instron machine (Model LM-150) was used at room temperature. To do this, the Instron is loaded with a 150kN cell for tensile test, 10kN cell for flexural test and with 25 mm extensometer which is connected to the data acquisition system and visualized through a computer screen. The test conditions are set for each sample of the six tests. The speed of the test is set at 2 mm/min to promote good representativeness and good result.

2.2.3. Scanning Electron Microscope Analysis SEM

- The surface of the fibers was analyzed before and after treatment with the coupled scanning electron microscope EDX. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi) was used.

2.2.4. Spectroscopy ATR-FTIR

- The IR analysis was carried out on 5 micrograms of a sample of each type of fiber. The Nicolet IS10 FT-IR spectrometer was used to analyze functional groups before and after fiber treatment.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Fibers and Composites by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- The raw fibers (figure 4.A) have a rough surface which may be due to the presence of waxes, pectin, and oil on the one hand, and pores on the other. All these defects are not favorable to a good adhesion between fibers and polymer material. After the treatment (figure 4.B) of the fibers, a much flat surface is observed which does not contain pores and defects. In addition to these last characteristics of the treated fibers, there was a defibrillation of the fibers allowing to distinguish the fibrils. The presence of fibrils is an asset for good cohesion between the elements of the composite. The Figure 4.D shows a lot of defects in the area between the fibers and the matrix. These defects may be due to poor homogenization between the fibers and the matrix, either a poor adhesion between them on the one hand or that an insufficient fiber to fill the whole matrix is the cause.

| Figure 4. SEM analysis: A- Raw fibre, B- Treated fiber, C- composite LDPE-treated fiber; D- composite LDPE-untreated fiber |

3.2. Spectroscopy ATR-FTIR

- The figure 5. shows the IR of fibers treated with 6% w/v NaOH and untreated fibers. Considering the spectrograms of the raw and treated fibers, a change is noted after the treatment of the fibers. The vibration of C-O groups characterized by the wavelength 1031 cm-1 corresponds to cellulose and has hemicellulose. Previous work by Tufan and al. [24] confirmed this. The peaks corresponding to wavelengths between 2846 cm-1 and 2935 cm-1 express the asymmetric elongation vibration of the C-H bonds in the CH2 group. In addition, the peak between 3399 cm-1 and 3480 cm-1 is practically non-existent for the ET6% NaOH spectrogram but appears clearer and broader for the raw fibers and ET6% NaOH. This shows that NaOH has played the role of leaching by releasing hydroxyl functions. The presence of OH at 1644 cm-1 is specific to the water molecule. This treatment not only improves the properties of composites, but also their durability against environmental factors such as humidity.

| Figure 5. Fourier infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) on treated and untreated fibers |

3.3. Mechanical Test

3.3.1. Tensile Strength

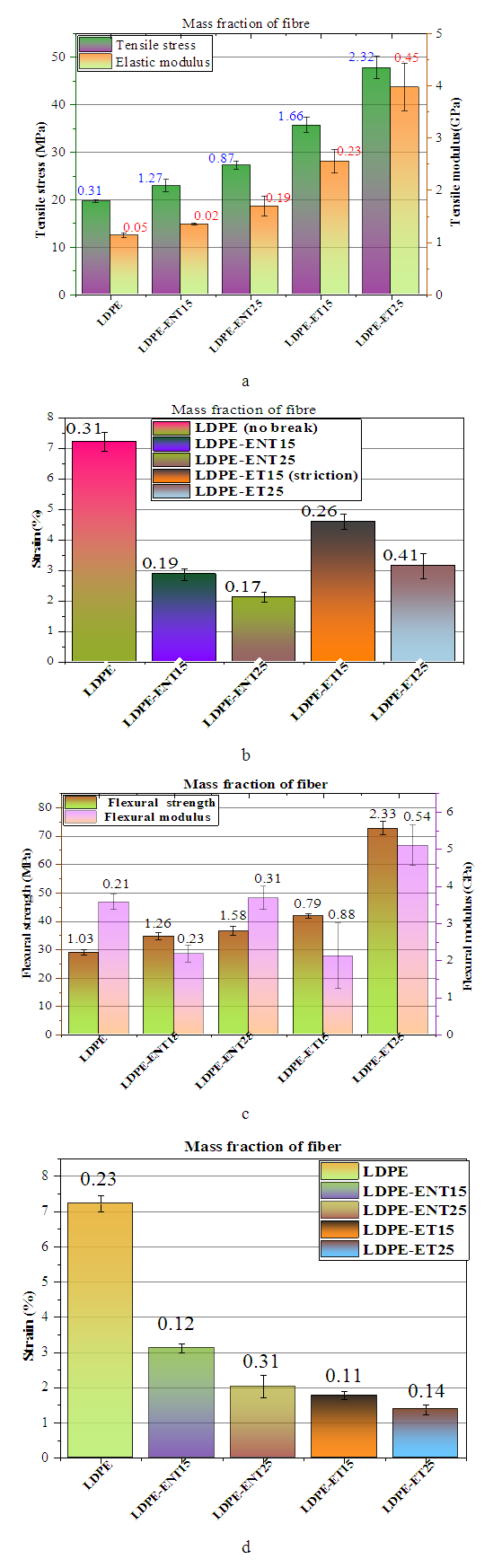

- The figure 6.a show the effect of chemical treatment and the content (%m) of eucalyptus fibers on the properties of tensile strength, tensile elastic modulus as well as on the fracture deformation of LDPE/Eucalyptus bio-composite materials. However, with or without fiber treatment, the tensile strength and tensile modulus increase linearly for all composites tested according to the mass load of the fibers. The modification of the fiber improves its hydrophobic character, decreases its roughness as well as wettability to water or humidity. According to Ma Xiaofei and al. [25], Santos and al. [26], the use of a binder improves the interface of the composite which improves the tensile properties of the composite. Relative to the treatment or not of the fibers, an increase of 56.03% in the tensile strength of LDPE-ET15 composites compared to LDPE-ENT15 composites is obtained, because, according to the SEM, the surface morphology has been modified from a rough, porous surface to an improved, smoother surface. The same observation is made for LDPE-ET25 composites compared to LDPE-ENT25 composites, which represents a 75.72% increase. Chemical treatment of fibers has improved the strength of fibers and the interface of composites. Chemical treatment of fibers improves the quality of fibers, therefore increasing tensile properties of composites [27] [28] [29]. It is also noted that the fiber content influenced the tensile properties, i.e., an increase of 16.57%; 38.82%; 81.89%; 143.93% respectively of the LDPE-ENT15, LDPE-ENT25, LDPE-ET15 and LDPE-ET25 composites is obtained. Considered as a reinforcement to improve the mechanical properties of materials, it is accepted that when increasing the load of the fibers, this induces the performance of the composite by increasing its tensile strength. This is confirmed by literature [30], [31]. The work of Benyahia and al. [32] confirmed this hypothesis when they found a 50% increase in the tensile strength of the composite (unsaturated polyester-Alfa fiber) by treating the Alfa fibers with 7%w/v NaOH. The improvement in ultimate tensile strength is due to good adhesion between the treated fibers and the polymer [21], [33], also, the increase in mass fraction increases these tensile properties [34]. The deformation (figure 6.b) observed is much greater for virgin LDPE. But no rupture occurred. The greater the applied load, the more the specimen stretches causing a strong striction to the entire surface of the specimen. In contrast, LDPE-ET15 composites did not undergo a rupture at the deformation but presented a much more distinct area of striction than that of LDPE. The increase of young’s modulus of tensile strength in the treated fiber composites would be related to the crystallinity of cellulose II [34] obtained by NaOH treatment. In other words, the periodicity of the crystalline node of cellulose would be the cause of this improvement.

3.3.2. Flexural Strength of Composites

- The bending parameters such as strength, modulus of elasticity and fracture deformation are shown in figure 6.c.d. The observations are also noted as that of traction. However, a linear evolution of the bending stress is observed for all composites. Indeed, it is determined that improvements of 20.92%, 99.72% respectively of LDPE-ET15 composites compared to LDPE-ENT15 composites, and LDPE-ENT25 composites compared to LDPE-ET25 composite are allowed. This shows that the alkali treatment of the fibers has increased the flexural strength as well as its Young’s modulus but decreases the deformation at the rupture of the same composites tested of the same order. This is confirmed by literature [35], [36]. If some composites other than LDPE and LDPE-ENT15 are less ductile and undergo the rupture with a small deformation, it is because new surfaces have been created that are propagated in all directions, which makes them fragile and consequently their rupture. On the other hand, the concentration of NaOH as well as the processing time have a significant influence on the nature of the fiber obtained. Since the stiffness of the fibers is in part highly dependent on the presence of lignin, and if this, following alkaline treatments, undergoes the phenomenon of release, the fiber becomes more fragile and its mechanical contribution in terms of strength in the composite is reduced. This is confirmed by the work of Rokbi and al. [37]. The rupture for LDPE-ENT15 and LDPE-ENT25 is noted for all mechanical tests (figure 6.d) conferring their rigid character.

| Figure 6. Tensile test (a- maximum strength, b- strain); Flexural test (c- maximum strength, d- strain) |

3.3.3. Charpy Impact

- Figure 7. shows the results of the impact tests. These results are obtained by averaging the 5 samples tested. The resilience (81.79 1.56 kJ/m2) is much higher for LDPE specimens without treated or untreated fibers, which characterizes their ductility. Also, the LDPE-ET25 bio-composites have a high Charpy shock resilience (78.88 ± 1.66 kJ/m2) compared to that of the LDPE-ENT25 composites (25.05 ± 1.17 kJ/m2), an improvement of 68.24%. The same observation is made for the composites LDPE-ET15 (37.45 ± 1.12 kJ/m2) and LDPE-ENT15 (18.86 ±1.02 kJ/m2), which represents a 49.64% improvement. The work of P. Nguyen Tri and al. [38] showed a 23% increase in the Charpy impact resistance of bamboo fiber composites treated with NaOH solution compared to untreated same-fiber composites. Moreover, the fiber content influenced this same mechanical property. There is a decrease in the Charpy shock resistance, depending on the amount of fiber compared to blank LDPE (81.79 ± 1.56 kJ/m2), LDPE-ET25 composites (78.88 ± 1.66 kJ/m2), LDPE-ET15 (37.45 ± 1.12 kJ/m2), LDPE-ENT25 (25.05 ± 1.17 kJ/m2) and LDPE-ENT15 (18.86 ± 1.02 kJ/m2). This represents a decrease of 3.69%, 54.21%, 69.37% and 76.94% respectively. This decrease in shock resilience due to the increase in the mass fraction of fibers is shown by the work of some authors of the literature [39], [40], [41]. The absorption of impact energy by the fibers is dependent on detachment, tensile and fracture. However, the peel-off energy released by the take-off and fracture is proportional to the take-off length. Therefore, the low adhesion between the matrix and the fiber thus predisposes the material to a greater absorption energy [39]. But this reason is only confirmed by considering the LDPE-ENT25 and LDPE-ENT15 REM imaging of the figure. In addition, the decrease in impact resistance can be predicted (SEM figure 4) by considering the formation of micropores; discontinuity zones; phase inequality and material rigidity, as reported by Morreale and al. [42] who studied the same property by adding wood meal fiber to a starch-based biopolymer matrix. We can also attribute this decrease in resilience to the stiffness of the fibers. Untreated fibers are stiffer than treated ones, therefore untreated fiber reinforced composites (LDPE-ENT15 and LDPE-ENT15) are stiffer and exhibit low resilience.

| Figure 7. Resilience Charpy of composites |

4. Conclusions

- Many studies have been conducted on the alkaline treatment of fibers while varying the concentration in active elements to optimize the treatment. The literature shows that NaOH concentration is not fixed for natural fiber processing. However, the choice of NaOH concentration is made after a variation of this latter leading to obtaining much better properties. In addition, this study allowed to find an improvement of 16.57%; 38.82%; 81.89%; 143.93% respectively of LDPE-ENT15, LDPE-ENT25, LDPE-ET15 and LDPE-ET25 for all the traction samples. Also, an improvement of 20.92%, 99.72% respectively of LDPE-ET15 compared to LDPE-ENT15 and LDPE-ET25 compared to LDPE-ENT25. The materials reinforced by treated fibers resist better to Charpy shocks than those of untreated fibers, that is a maximum resilience of 78.88 1.66 kJ/m2 for LDPE-ET25. Roy and al. [43] treated jute fibers with 0.25%-1.0% NaOH for 0.5 to 48h and found that the alkaline treatment increased tensile strength and elongation at break by 82% and 45% respectively. Abral and al. [6] also showed that alkaline treatment of screw pine fibers resulted in high mechanical properties compared to untreated fiber composites.Comparing these literature results with those found in this work, it emerges that alkaline treatment of natural fibers improves the mechanical properties of composites whatever the %NaOH content. To contribute to the reduction of polymers generated in the Mauritian municipality of Quebec (Canada), for example, and to adapt technology transfer for the municipality of Lomé (Togo), the fibers treated with 6% (w/v) NaOH in this study will be used to reinforce recycled low-density polyethylene to produce ecological paving stones and any other useful eco-product.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the laboratories of the University of Québec at Trois-Rivieres in Canada and the Université de Lomé and Kara in Togo and would like to express their gratitude to the rectorate of UQTR and the presidency of UL for the cotutelle for this study.

Conflicts of INterest

- There are no conflicts to declare.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML