-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Chemistry

p-ISSN: 2165-8749 e-ISSN: 2165-8781

2025; 15(4): 89-101

doi:10.5923/j.chemistry.20251504.02

Received: Oct. 20, 2025; Accepted: Nov. 16, 2025; Published: Nov. 25, 2025

Elimination of Phosphate Ions by Coupling Adsorption/Electrocoagulation Processes Using Activated Carbon from Hyphaene thebaica Kernels and Iron Electrodes

Blaise Kom1, Richard Domga2, Balike Musongo3, Romuald Teguia Doumbi1, Lys Carelle Motue Waffo1, Bruno Fachakbo1, Serge Raoul Tchamango1

1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Ngaoundere, Ngaoundere, Cameroon

2Department of Applied Chemistry, National School of Agro Industrial Sciences, University of Ngaoundere, Ngaoundere, Cameroon

3Department of Chemical Engineering, School of Chemical Engineering and Mineral Indistries, University of Ngaoundere, Ngaoundere, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Blaise Kom, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Ngaoundere, Ngaoundere, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In this work, phosphate ions were removed from aqueous solutions through adsorption (AD) with activated carbon (AC), electrocoagulation (EC) with iron electrodes, and both processes combined (adsorption and electrocoagulation). Batch mode adsorption experiments were conducted to evaluate the influence of certains parameters, including solution pH, adsorbent dosage, time contact, and initial phosphate concentration. The results of adsorption process showed that maximum phosphate ions removal was reached after 20 minutes, and under acidic conditions. This removal increased with the increase of initial phosphate concentration while decreasing with increased adsorbent dosage. The maximum adsorption capacity of AC for phosphate was determined to be 16.24 mg/g. Kinetics data analysis revealed that phosphate ions adsorption followed a pseudo-second order model. During electrocoagulation process, various operational parameters were investigated, including current intensity, initial phosphate concentration, initial pH, supporting electrolyte concentration, and electrolysis time. The obtained results showed that 97.14% of phosphate ions were eliminated under optimal conditions: 50 minutes duration, 100 mA current intensity, 40 mg/L initial phosphate concentration, pH 9, and 2g/L NaCl concentration. The coupling of AD/EC and EC/AD processes in two simultaneous steps was also examined, with time being the only parameter varied. The obtained results leaded to 99.58% phosphate ions removal after 30 minutes of treatment, higher than respective removals of 82.66% and 97.14% by adsorption and electrocoagulation used individually.

Keywords: Activated carbon, Adsorption, Electrocoagulation, Hyphaene thebaica, Iron electrodes, Phosphates ions

Cite this paper: Blaise Kom, Richard Domga, Balike Musongo, Romuald Teguia Doumbi, Lys Carelle Motue Waffo, Bruno Fachakbo, Serge Raoul Tchamango, Elimination of Phosphate Ions by Coupling Adsorption/Electrocoagulation Processes Using Activated Carbon from Hyphaene thebaica Kernels and Iron Electrodes, American Journal of Chemistry, Vol. 15 No. 4, 2025, pp. 89-101. doi: 10.5923/j.chemistry.20251504.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

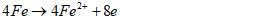

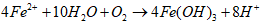

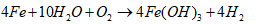

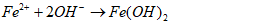

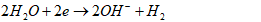

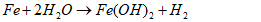

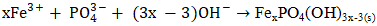

- Water plays a critical role in daily consumption and hygiene needs, serving as an indispensable element for all terrestrial life forms. Moreover, water is vital in various industrial processes such as beverage production, food preparation, and sanitation [1], [2], [3]. However, uneven distribution of water resources across agricultural, livestock, mining, washing and industrial sectors poses significant challenges in accessing clean water [4]. Contaminated water sources harbor various harmful compounds that can induce numerous adverse effects on both human health and ecosystem integrity [5]. Nowadays, the use of water becomes a persistent concern for governments, particularly in developing countries. Many diseases are directly linked to water, due by the discharge of untreated wastewater into the environment. Furthermore, industrial and anthropogenic activities are major contributors to water pollution, introducing toxic chemicals such as organic pollutants (e.g. aromatic compounds, pesticides, hydrocarbons) and inorganic pollutants (e.g. nitrates, phosphates, heavy metals like Cr, Pb, Cd, Hg) into aquatic environment [6]. Municipal wastewater, for instance, contains approximately 25 mg/L of phosphates, orthophosphates, and polyphosphates [6]. Elevated concentrations of these pollutants (above 0.20 mg/L) can trigger excessive algae growth, leading to lakes and rivers eutrophication. Eutrophication, caused by an ecosystem receiving an abundance of nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, contributes to degradate water quality and renders it unsuitable for various uses [7]. This degradation has detrimental effects on human health, the environment, and local economic activities [8].Given the need to mitigate water pollution, various treatment methods have been developed, including physicochemical processes (ion exchange, membrane technologies, chemical precipitation) and biological processes (biofiltration, activated sludge, lagoons) [9], [10]. However, these methods often have insufficiencies. For instance, ion exchange and membrane techniques transfer pollutants from the liquid phase to solid phase without destroying them, generating secondary waste at high costs. Chemical precipitation and coagulation require multiple stages, strict pH control, and expensive chemicals, resulting in significant sludge production. Biological methods necessitate sludge removal and treated water disinfection, also contributing to secondary pollution [11]. Given these limitations, we have chosen environmentally-friendly processes: activated carbon adsorption and electrocoagulation. These processes are simpler, less expensive, less restrictive, and utilize locally available waste materials. Activated carbon adsorption is noted for its large surface area, micro porous structure, and high pollutant adsorption capacity, although industrial activated carbon's cost and regeneration challenges limit its widespread application [12]. Consequently, recent studies have explored the feasibility of using activated carbon derived from natural materials such as agricultural and industrial waste for pollutant removal [13], [14], [15]. In this study, activated carbon will be produced from agricultural waste (HT) core shells.Electrocoagulation is an electrochemical process with sacrificial soluble aluminium or iron anodes. In this process, the action of a convenient current frees metal ions (Al3+, Fe2+ or Fe3+) by anode oxidation. These ions combine then with hydroxyl ions released at the cathode, leading to aluminium or iron hydroxides and enhance flocks formation [16], [17]. When iron electrodes are used, the following mechanisms could explain the observed phenomena [16], [18], [19].Mechanism 1At the anode:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

- All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade (NaCl, 99%; NaOH, 99%; H2SO4, 96%, (NH4)2MoO4, 98% C6H8O, 99% and KH2PO4, 98%). The synthetic wastewater in this study was prepared from KH2PO4. Test solutions were prepared using ultra-pure Milli-Q water (Millipore, resistivity > 18 MΩ cm).

2.2. Adsorbent Materials

- To convert local materials into activated carbon, Hyphaene thebaica (HT) core shells were used as the adsorbent. Fruits of HT were sourced from the local market. The fruits were peeled, washed with tap water, dried for 4 days, and then crushed to separate the shells from core. The shells were collected for further processing. Figure 1 illustrates different parts of these fruits.

| Figure 1. Hyphaene thebaica (a) fruits, (b) peeled fruits, (c) stone shells |

2.3. Preparation of Activated Carbon

- The core collected previously were ground and sieved to retain fractions less than 200 µm, then dried in an oven at 105°C for 24 hours. The preparation proceeded in three main stages: Carbonization (pyrolysis) of the ground biomass at 600°C in a programmable Nabertherm muffle furnace with a heating rate of 2.5°C/min for 3 hours. The resulting material was cooled to room temperature and then impregnated with ortho-phosphoric acid solution. After stirring for 24 hours at room temperature using a Mivar Magnetic Stirrer, the impregnated material was filtered, washed with distilled water until reaching a constant pH (measured using a HANNA HI 2209 pH meter), and dried in an oven at 105°C for 24 hours. The dried material was subsequently cooled in a desiccator for 24 hours [24].

2.4. Characterization of Activated Carbon

- Physicochemical tests included determination of pyrolysis yield, ash content, moisture content, adsorption capacity and specific surface area were carried out on the prepared activated carbons to evaluate their quality and performance.

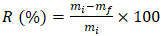

2.4.1. Pyrolysis Yield

- The pyrolysis yield, expressed as a percentage, reflects the mass loss during pyrolysis and was calculated using Equation 9.

| (9) |

2.4.2. Dry matter Content

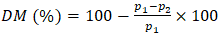

- The dry matter content was determined following [25] standards by drying a sample at 105 ± 2°C until a constant weight was achieved. The dry matter content (DM) is calculated using Equation 10.

| (10) |

2.4.3. Ash Content

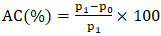

- Ash content (AC) was determined according to [25] by heating a sample in an oven and calculating the ash content using Equation 11.

| (11) |

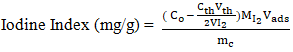

2.4.4. Iodine Index

- The iodine index, a measure of the adsorbent's ability to adsorb small molecules, was determined according to AWWA B 600-78 standard [26]. The iodine index is calculated using Equation 12.

| (12) |

Initial concentration of iodine solution (mol/L).

Initial concentration of iodine solution (mol/L). Concentration of sodium thiosulfate solution (mol/L);

Concentration of sodium thiosulfate solution (mol/L); Volume of thiosulfate poured to the equivalence (mL);

Volume of thiosulfate poured to the equivalence (mL); Volume of iodine measured (mL);

Volume of iodine measured (mL); Molar mass of iodine (g/mol);

Molar mass of iodine (g/mol); Adsorption volume (mL);

Adsorption volume (mL); Mass of adsorbent (g).

Mass of adsorbent (g).2.4.5. Determination of Methylene Blue (MB) Index

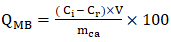

- The methylene blue index (QMB) was used to evaluate the macroporosity and mesoporosity of activated carbons. The MB index was calculated using Equation 13.

| (13) |

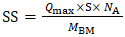

2.4.6. Specific surface

- The specific surface (SS) area was estimated based on the adsorption capacity of the adsorbent for a given solute, calculated using Equation 14.

| (14) |

2.4.7. pH at Point of Zero Charge (pHZPC)

- The pHZPC was determined using the solid addition method with NaCl solutions at different pH values, and the pH was measured after stirring for 24 hours [27].

2.4.8. Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

- FTIR spectroscopy was employed to identify functional groups in raw and activated Hyphaene thebaica materials.

2.5. Batch Adsorption Experiments

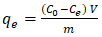

- Adsorption capacity of activated carbon (AC) was evaluated by mixing AC with phosphate ions solution, followed by filtration and UV-visible spectrophotometry analysis to determine residual phosphate ions concentrations. Adsorption capacities were obtained using Equation 15.

| (15) |

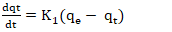

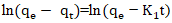

2.6. Modeling of Adsorption Kinetics

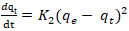

- Pseudo-first order model: The pseudo-first order model was applied to describe adsorption kinetics using Equation 16 and 17.

| (16) |

| (17) |

Rate constant of the pseudo first order model (min-1);

Rate constant of the pseudo first order model (min-1); Adsorption capacities, respectively at time t and at equilibrium (mg/g).Pseudo-second order model: The pseudo-second order model was used to characterize chemisorption kinetics using Equation 18 and 19.

Adsorption capacities, respectively at time t and at equilibrium (mg/g).Pseudo-second order model: The pseudo-second order model was used to characterize chemisorption kinetics using Equation 18 and 19. | (18) |

| (19) |

Rate constant for second order kinetics expressed (g.mg- 1.min- 1);

Rate constant for second order kinetics expressed (g.mg- 1.min- 1); Adsorption capacities, respectively at time t and at equilibrium ( mg/g).

Adsorption capacities, respectively at time t and at equilibrium ( mg/g).2.7. Adsorption isotherms

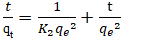

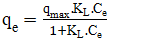

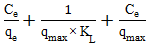

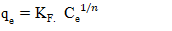

- The Langmuir isotherm model was employed to analyze the adsorption equilibrium data using Equation 20 and 21 and the Freundlich isotherm model was used to describe multilayer adsorption using Equation 22 and 23.

| (20) |

| (21) |

Concentration at equilibrium (mg/L);

Concentration at equilibrium (mg/L); Quantity adsorbed at equilibrium (mg/g);

Quantity adsorbed at equilibrium (mg/g); : Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g);

: Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g); Langmuir equilibrium value (L/mg).

Langmuir equilibrium value (L/mg). | (22) |

| (23) |

Adsorbed quantity (mg/g);

Adsorbed quantity (mg/g); Balance concentration (mg/L);KF and n: Freundlich constants associated with adsorption capacity and adsorption affinity and adsorption affinity, respectively (L/g).

Balance concentration (mg/L);KF and n: Freundlich constants associated with adsorption capacity and adsorption affinity and adsorption affinity, respectively (L/g).2.8. Electrocoagulation

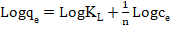

2.8.1. Electrochemical Reactor

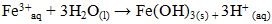

- A 250 mL beaker was used as reactor during the experiments (Figure 2). The volume of effluent to be treated was 200 mL. Two iron electrodes of the same size were used, each with a length of 5 cm and a radius of 0.5 cm. They were positioned 2 cm apart a distance chosen to minimize ohmic drop yet sufficient to prevent clogging and ensure effective agitation. Before electrolyses, NaCl was added to the solution to ensure the conductivity of the medium. The pH of the solutions was adjusted by adding NaOH and H2SO4 (0.1 N).

| Figure 2. Electrochemical device: 1-Magnetic stirrer, 2-Magnetic bar, 3-Anode (Iron), 4-Cathode (Iron), 5-Electrochemical cell, 6-D.C power supply |

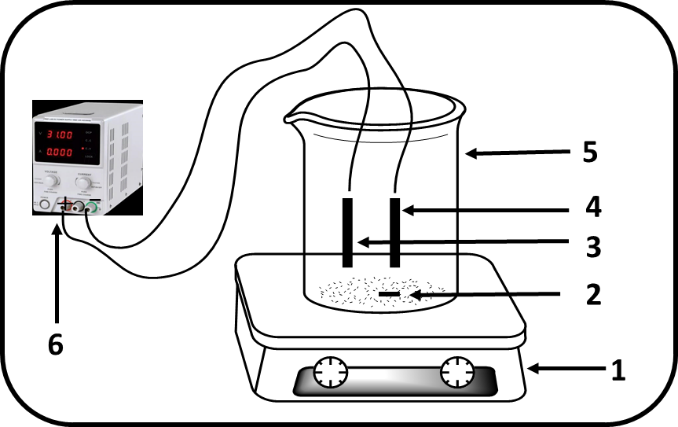

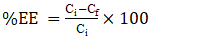

2.8.2. Analytical Measurements

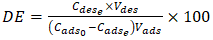

- The titration of phosphate ions was conducted using UV-Visible spectrophotometry. The residual phosphate concentration was determined after the formation of a phosphomolybdic complex. In acidic medium and in the presence of ammonium molybdate, orthophosphates form a phosphomolybdic complex, which, when reduced by ascorbic acid, develops a blue color [28]. The efficiency of phosphate ion removal was determined using Equation 24 and the desorption efficiency (DE) using Equation 25.

| (24) |

| (25) |

Initial concentration of PO43- (mg/L);

Initial concentration of PO43- (mg/L); Final concentration of PO43- (mg/L);EE: Removal efficiency (%);

Final concentration of PO43- (mg/L);EE: Removal efficiency (%); : Concentration of phosphate ions desorbed at equilibrium (mg/L);

: Concentration of phosphate ions desorbed at equilibrium (mg/L); : Initial concentration of phosphate ions (mg/L);

: Initial concentration of phosphate ions (mg/L); : Volume of adsorption solution (L);

: Volume of adsorption solution (L); : Volume of desorption solution (L).

: Volume of desorption solution (L).2.9. Coupling of Adsorption/Electrocoagulation Processes

- The coupling was carried out by introducing, which stirring the activated carbon into the electrocoagulation reactor containing the solution to be treated. After adsorption, the electrocoagulation process was carried out. Furthermore, another coupling was carried out by first performing electrocogulation, followed by the actived carbon adsorption process.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Adsorption Process

3.1.1. Physico-chemical Characteristics of Activated Carbon

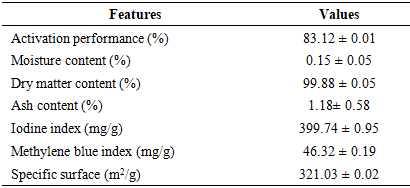

- Table 1 presents the physicochemical characteristics of the activated carbon used in this study. The activation yield of 83.12% indicates a loss of 16.88% of the carbonaceous material (CA), attributed to the washing process with distilled water to remove activating agents. In fact, during washing, some carbon particles clog filter paper while others are carried away by rinsing water.

|

3.1.2. pH at Point of Zero Charge (pHPZC)

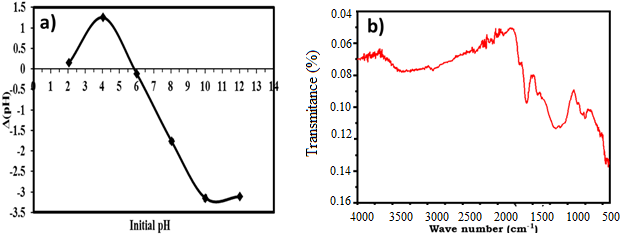

- The pH at the point of zero charge (pHPZC) provides information regarding the adsorbent's surface charge. It is the pH value of the solution where the net charge on the surface becomes zero, balancing the positive and negative charges. The adsorption of molecules or ions onto a solid surface is significantly influenced by the pH of the medium, particularly at the pHPZC where the surface charge is neutral. Figure 3.a illustrates the pH point of zero charge (pHPZC). According to Figure 3.a, the pHPZC of the activated carbon (AC) is 5.9. This pH value indicated that the surface charge of the AC becomes neutral. Consequently, for adsorbates with pH values below the pHPZC (pH < 5.9), the surface of the produced carbonaceous adsorbent (CA) is positively charged, thereby favoring the adsorption of anionic species. Conversely, for solute pH values above the pHPZC (pH > 5.9), the CA surface carries negative charges, which promotes the adsorption of cationic species. The pHPZC value of 5.9 closely matches that reported by [31] using the same precursor, HT, who obtained a pHPZC of 6.

3.1.3. Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

- Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is a crucial analytical technique utilized for identifying characteristic functional groups involved in adsorption chemistry. Figure 3.b presents the FTIR spectrum of coal-based shells derived from Hyphaene thebaica cores.The prominent absorption bands at (407.56 - 565.80) cm-1 are attributed to the stretching vibration of –OH. The peak at 1428.43 cm-1 corresponded to the stretching vibrations of –CH2. The band observed at approximately 1681.52 cm-1 is indicative of –COOH, while the peak around 1375.29 cm-1 is associated to phenol group. The characteristic peak at 889.92 cm-1 is attributed to the C–O bending vibration in –COH. The band at approximately 752.26 cm-1 was related to the out-of-plane bending mode of O–H. The range (2250-2400) cm-1 corresponded to the C≡C stretching vibration, characteristic of alkyne group. Overall, the AC surface exhibits abundant functional groups, particularly –OH, –COOH, and –COH. These polar functional groups enhanced the adsorption of polar solutes. The presence and enhancement of these functional groups in the adsorption capacities of AC corroborated the findings of [33].

| Figure 3. a) Zero Charge Point pH (pHZPC) of AC derived from Hyphaene thebaica core shell, b) FT-IR spectrum of AC |

3.1.4. Influence of Adsorption Parameters

3.1.4.1. Influence of Time Contact

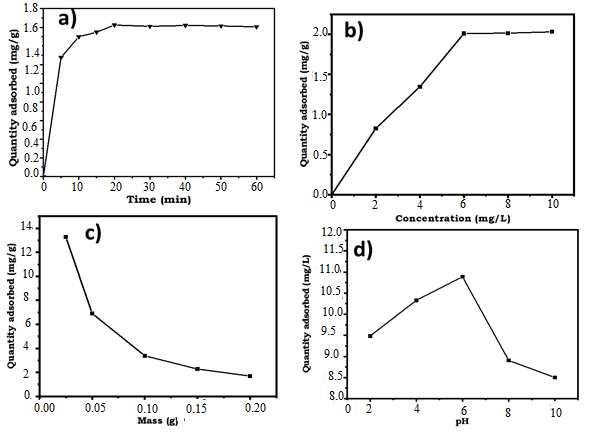

- The influence of contact time on phosphate ion adsorption was studied at room temperature with 0.10 g of adsorbent and a solution concentration of 6.00 mg/L of PO43-. Figure 4.a illustrates the time-dependent adsorption process. Two distinct phases were observed: an initial rapid increase in adsorbed phosphate quantities from t = 0 min to t = 20 min, attributed to the availability of vacant active sites and strong affinity between phosphate ions and the adsorbent [34]. Subsequently, from t = 30 min to t = 60 min, a plateau phase was observed, indicating the saturation of the adsorption sites on the activated carbon surface. The equilibrium time for phosphate ion adsorption was determined to be 20 minutes, achieving adsorbed quantities of 15.47 mg/g and 16.24 mg/g from an initial concentration of 6.00 mg/L.

3.1.4.2. Influence of Initial Concentration of Phosphate Ions

- The effect of initial phosphate ion concentration on adsorption is depicted in figure 4.b. As seen in this figure, higher initial concentrations resulted in the increase the quantity of adsorbed phosphate ions, with adsorption rising from 0.83 mg/g to 2.03 mg/g as concentration increases from 2.00 mg/L to 10.00 mg/L. This phenomenon is attributed to greater availability of phosphate ions and their stronger driving force toward adsorbent sites [35]. A concentration of 6.00 mg/L is used for further study, as beyond this concentration, adsorbed quantities of phosphate ions show minimal variation.

3.1.4.3. Influence of Activated Carbon Mass

- Figure 4.c depicts the influence of adsorbent mass on adsorbed phosphate quantities. Increasing adsorbent mass initially increases adsorption, but beyond 0.10 g, the curve representing adsorbed quantities reaches a plateau, indicating saturation of active sites and reduced accessible surface area due to particle agglomeration [36]. The adsorbed quantities decrease from 62.71 mg/g to 7.89 mg/g, Starting at 0.1 g of activated carbon, the amounts of adsorbed phosphate ions hardly vary anymore.

3.1.4.4. Influence of pH During Adsorption

- Figure 4.d shows the influence of solution pH on adsorbed phosphate quantities. As shown in this figure, maximum adsorption occured at pH 6, attributed to electrostatic attraction and ion exchange between phosphate ions and the carbon surface [40]. At lower pH, positively charged surface sites dominated, facilitating phosphate ion adsorption via electrostatic forces. At pH > 6, competition between phosphate ions and hydroxyl ions (OH-) for adsorption sites reduces phosphate adsorption. The optimal pH of 6 corresponds to the point of zero charge (pHZPC) of the adsorbent, where surface neutrality enhances adsorption efficiency due to minimized electrostatic interactions and increased availability of active sites [39].

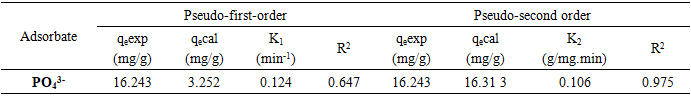

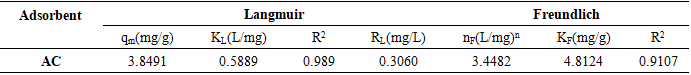

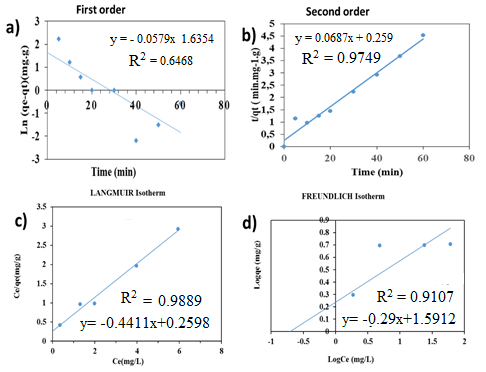

3.1.5. Modeling of Adsorption Kinetics

- To better describe the adsorption mechanism of phosphate ions on activated carbon (AC), two kinetic models were applied to these experimental data: The pseudo first-order model and the pseudo second-order model. These models elucidate the variation in solute quantity adsorbed on a solid support over time, aiming to identify the mechanisms governing adsorption rate. Figures 5.a-b and Table 2 demonstrate that both orders kinetic models (pseudo first-order and pseudo second-order) are applicable for phosphate ions retention across various ion concentrations. This is supported by high correlation coefficients (R² = 0.97 > 0.95) (Figure 5.b). Additionally, the calculated adsorbed quantity closely matches experimental results, further validating the applicability of these models for phosphate ion retention on our adsorbent.

|

3.1.6. Modeling of Adsorption Isotherms

- The experimental results were modeled by two isothermal theoretical models to describe the equilibrium adsorption process: Langmuir and Freundlich models. The values of correlation coefficients R2 and the constants characterizing the adsorption equilibrium of phosphate ions on the AC for two models (Langmuir and Freundlich) are presented in Table 3 and Figures 5.c-d. From this table, it appeared that Langmuir model was more appropriate the Freundlich one for describing the adsorption of phosphate ions with a better correlation coefficient (R2 ˃0.95). On the other hand, the RL value is between 0 and 1, thus proving a good adsorption capacity of the adsorbent and a favorable adsorption reaction. According to the Langmuir model, the KL value indicated that there is adsorption of phosphate with the formation of a monolayer on the adsorbent surface. This involved localized adsorption on well-defined adsorbent sites, likely to bind only a single molecule [40].

|

3.2. Influence of Parameters on Electrocoagulation

3.2.1. Influence of Current Intensity

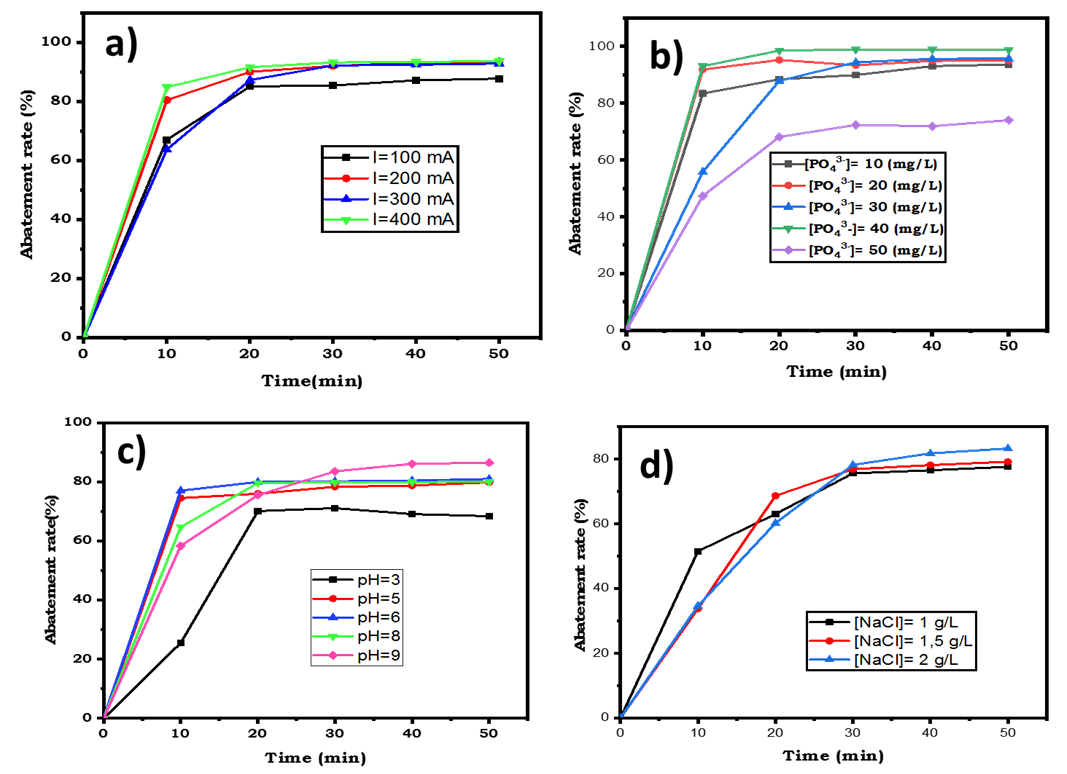

- Current intensity is a pivotal factor in electrocoagulation and is directly controllable [23]. So, a series of tests were conducted with current intensities ranging from 100 mA to 400 mA, while keeping other parameters constant. As shown in Figure 6.a, phosphate removal efficiency exhibited similar trend, characterized by rapid increase in phosphate removal during the first ten minutes, whatever the imposed current. After 30 minutes of electrocoagulation, a plateau is observed in all the curves. Then more than 85% phosphate removal was eliminated, when the imposed current was 200, 300 and 400 mA. This was not surprising, because according to Faraday’s the increase of the current intensity produces a great amount of ferrous and ferric ions are electro-generated and formed hydroxide compounds capable to fix pollutants [19].

3.2.2. Influence of Initial Phosphate (PO43-) Concentration

- Studying the influence of initial phosphate concentration assessed the process's capability to remove high levels of phosphate ions. Experiments were conducted using phosphate solutions with concentrations of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg/L. Figure 6.b shows that all concentration curves exhibited similar behavior: rapid reduction followed by a plateau. Notably, the reduction is fastest at 10 minutes for all initial concentrations except at 50 mg/L, where phosphate removal rates increase over time before reaching a plateau. At high initial concentrations (50 mg/L), phosphate elimination rates are lower. Treating solutions with higher initial concentrations requires longer reaction times to achieve complete phosphate removal [23].

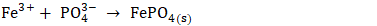

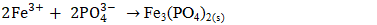

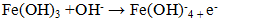

3.2.3. Influence of pH During Electrocoagulation

- To investigate the impact of pH on phosphate removal, experiments were conducted at following pH: 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9. Previous works explained mechanisms occurring during phosphate elimination when iron is used as electrode material [41], [42]. It has been shown that FePO4(s) is formed in the low pH range (<6.5) and in the high pH range (>6.5). FePO4(s) has minimum solubility within pH range of 4.5–5.5, but its solubility increases with increasing pH according to following reactions [41], [43], [44].

| (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

3.2.4. Influence of Supporting Electrolyte Concentration

- The conductivity of the reaction medium was varied by adding NaCl, this salt being used as supporting electrolyte. Figure 6.d illustrates the influence of medium conductivity on phosphate elimination during electrocoagulation (EC). The curves in Figure 6.d showed similar trend, initially increasing and stabilizing between 30 and 50 minutes, with phosphate removal efficiency improving with increasing NaCl concentration. NaCl addition enhances current passage through the EC cell, facilitating both electrochemical and chemical dissolution of iron electrodes (Equations 29 and 30). The latter depends on the equilibrium potential of the iron species and the overvoltages (anodic and cathodic).

| (30) |

| (31) |

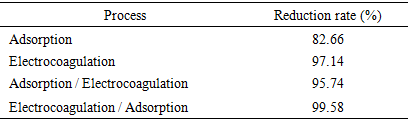

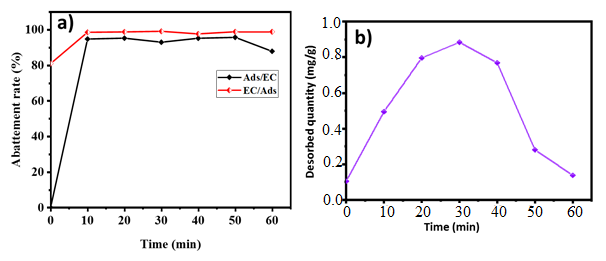

3.3. Coupling of Adsorption/Electrocoagulation Processes

- When used alone, the adsorption process achieved a phosphate removal rate of approximately 82.66%. In contrast, continuous electrocoagulation with iron electrodes, when used alone, attained an efficiency of approximately 97.14% of phosphate removal. Consequently, it was prudent to explore the combination of these two techniques to further reduce phosphate ions by varying the electrolysis time while maintaining the optimal conditions for both processes.Treatment times of 60 minutes were selected in this study based on the results obtained from each process used independently (Figure 7). As shown in Figure 7.a, the coupling effect on phosphate removal was investigated over a range of 0 to 60 minutes, as well as at the optimum conditions for each process. The introduction of the adsorbent material (activated carbon) into the electrocoagulation cell facilitated faster elimination. A total of 99.58% of phosphates were removed within 20 minutes. At the end of the treatment, the phosphate ion reduction rates were highly favorable, approaching 100%. The coupling of adsorption with electrocoagulation (Ads/EC) and electrocoagulation with adsorption (EC/Ads) yielded efficiencies of 95.74% and 99.58%, respectively (Table 4). The enhancement in phosphate ion removal with the addition of activated carbon can be attributed to the simultaneous benefits of both electrocoagulation and adsorption processes. It is evident that phosphate ion removal kinetics are rapid with electrocoagulation. The destabilization of colloids by in situ-generated cations and their adsorption onto metal hydroxide forms contribute to the reduced pollutant elimination time.

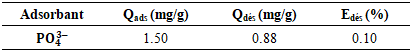

|

3.4. Regeneration of Adsorption Sites

- The regeneration of the activated carbon adsorption sites is performed using an aqueous solution of sodium chloride (NaCl) with a concentration of 4.00 g/L and a pH of 6. The study involved treating 100 mL of sodium chloride solution, containing 0.10 g of phosphate ions, under magnetic stirring (250 rpm) at room temperature. Figure 7.b illustrates the quantity desorbed as a function of time. It can be observed that initially, desorption curve decreases rapidly with stirring time. Then, between 40 and 50 minutes, the curve increases and subsequently decreases again at 60 minutes. This behavior can be explained by the large release of phosphate ions initially adsorbed by the activated carbon at the start beginning of the experiment. After 40 and 50 minutes, the release of ions into the medium began, and at 60 minutes, the regeneration process restarted.

|

4. Conclusions

- The aim of this study was to remove phosphate ions from an aqueous medium through adsorption onto activated carbon derived from Hyphaene thebaica core shells and via electrocoagulation. The physicochemical properties of the adsorbent revealed a combined micro and mesoporous structure, which plays a crucial role in the adsorption process. Infrared (IR) spectroscopy indicated that the adsorbent primarily contains polar functional groups that facilitate the adsorption of polar solutes. The results demonstrated that phosphate ion adsorption onto activated carbon from Hyphaene thebaica core shells occurs rapidly within 20 minutes or less. Conversely, the adsorbed quantity decreased with increased mass of the activated carbon. Linear regression analyses revealed that the adsorption kinetics conform to the pseudo-second order model. Langmuir model was observed, with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.95. Electrocoagulation proved effective for treating liquid effluents containing various pollutants. Evaluation of these parameters in the electrocoagulation process indicated that phosphate removal (97.14%) was more efficient than adsorption (82.66%). Combining these two processes achieved a significant removal rate of 99.58%.

Declaration of Competing Interests

- The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Suggestions for Improvement

- [1] After 40 and 50 minutes, the release of ions into the medium began. And at 60 minutes, the regeneration process restarted, please explain.Between 40 and 50 minutes, there is a gradual release of phosphate ions into the medium. This can be explained by competition at the absorption sites, changes in the pH of the medium, ionic strength, and Van der Waals interactions.[2] Destabilization of phosphates can occur through the neutralization of the colloidal surface by the positive species of the coagulant, why?The removal of phosphate ions is enhanced in an acidic environment, as the presence of H₃O⁺ ions in the environment causes strong interaction with phosphate ions and the acidic functions present on the surface of the activated carbon.[3] Phosphate ion removal kinetics are rapid with electrocoagulation, explain.The electrocoagulation process involves several phenomena simultaneously, including the use of current intensity to generate coagulants in situ that cause phosphate ions to agglomerate. Adsorption, on the other hand, requires a single surface reaction that is generally slow and sometimes reversible.[4] NaCl addition enhances current passage through the EC cell, why?During electrocoagulation, NaCl increases the conductivity of the electrical current in the medium while reducing electrical resistance and promoting the production of coagulants due to the dissolution of the electrodes.[5] At high initial concentrations (50 mg/L), phosphate elimination rates are lower. Why?The rapid saturation of adsorption sites, kinetic factors, and process limitations may explain the low removal of phosphate ions at high concentrations.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML