-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Bioinformatics Research

p-ISSN: 2167-6992 e-ISSN: 2167-6976

2021; 11(2): 49-58

doi:10.5923/j.bioinformatics.20211102.01

Received: Jun. 21, 2021; Accepted: Jul. 20, 2021; Published: Jul. 26, 2021

A Comparative Study on the Telemedicine Law Pre and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic; Comparison Analysis between Korea, and the US

Choi Yong-Jeon

Daejin University, Dept. of Law and Public Service, Hoguk-ro, Pocheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Correspondence to: Choi Yong-Jeon, Daejin University, Dept. of Law and Public Service, Hoguk-ro, Pocheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Aim and objectives: This study aimed to review the state of telemedicine legislations in the United States and South Korea and undertakes a comparative study of the legislations pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic as groundwork for a more meaningful adoption and execution of telemedicine. Methodology: A comprehensive desk research for regulatory and legal frameworks in telemedicine was performed. The process entailed making an online search for regulations, laws, policy briefs, case studies, green papers, reports, and policy recommendations in the period 1990-2021. Results and Findings: A major concern over telemedicine law in the pre- and post-Covid-19 healthcare system can largely be linked to legislative barriers. There are significant differences in telemedicine legislations between the two countries before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Like South Korea, the US federal governments also lifted restrictions to telemedicine. However, in the situations between the two countries differed substantially in the pre-COVID-19 healthcare system. South Korea completely banned telemedicine, which barred telemedicine practice across the country. On the other hand, a key legal impediment to telemedicine in the United States is tied to the existence of in-state licensure system and federal reimbursement policies that focus on Medicare. Recommendations: For both South Korea and the United States, there is a need to build regulatory flexibility into telemedicine to cater to demands from a range of cases. Among other elemental factors that can accelerate telemedicine expansion in the US and South Korea would be to develop robust legal standards to mitigate uncertainty and guarantee advantages like data security for using telemedicine in the two countries, and speeding up the processes of telemedicine regulations regardless of geographic delimitations.

Keywords: Telehealth legislations South Korea, Telehealth legislations United States, Telemedicine COVID-19, Telemedicine COVID-19 regulation South Korea, Telemedicine COVID-19 regulation United States

Cite this paper: Choi Yong-Jeon, A Comparative Study on the Telemedicine Law Pre and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic; Comparison Analysis between Korea, and the US, American Journal of Bioinformatics Research, Vol. 11 No. 2, 2021, pp. 49-58. doi: 10.5923/j.bioinformatics.20211102.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic radically contributed to the rapid adoption of telemedicine globally. However, there are many issues to be resolved to realize a full optimization of telemedicine in the context of South Korea [1,2,3]. During the COVID-19 outbreak, there was an incongruity in telemedicine practice across a number of countries, such as South Korea and the United States, because of legislative barriers. In South Korea, for instance, Seoul had a more developed medical infrastructure than rural and remote regions of Gangwon Province [2,3]. At the same time, the country lacked an established telemedicine law, as it was mostly mentioned in part in certain sections of the Medical Services Act. Accordingly, a major concern over telemedicine law in the pre- and post-Covid-19 healthcare system has extensively been linked to legislative barriers [4]. In effect, the regulatory dimensions of telemedicine entail accreditation, licensing, issues of privacy concerns, payment for services, and liability for medical negligence [5]. The call for statutory exceptions to telemedicine regulations in South Korea and the United States during the pandemic opened conversations on the need to allow post-COVID-19 healthcare systems to circumvent long-established legal and regulatory provisions to improve access to care.In the South Korean context, since the first person test positive for COVID-19 patient on January 20, 2020, and the number of infect persons spread to at least 20,000 by September 1, the government has attempted policy changes to institutionalize telemedicine [2-5]. The Association of Korean Medicine (AKOM) established COVID-19 telemedicine center of Korean Medicine (KM telemedicine center) to provided marginalized persons with medical services through telephone. Technically, however, telemedicine services are prohibited under the South Korean legislations [5]. The South Korean government only provisionally permitted telephone counselling as a measure to contain COVID-19 [6]. South Korea’s telemedicine is restricted under the Medical Services Act, which stipulates that “medical service must be provided by a licensed professional in a duly established medical institution” [7].In the case of South Korea, there have been calls for a review of associated regulations to permit telemedicine-medical diagnosis. In February 2021, for instance, the Federation of Korean Industries called for a need to pursue deregulatory actions, after a change in positive attitudes towards telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic [2,3,8]. A health industry study conducted by Federation of Korean Industries revealed that as much as 62.1 percent of Koreas favoured the need to introduce telemedicine [9]. Similar sentiments have been echoed by International Healthcare Center of Inha University Hospital, prompting a need to compare Korean’s telemedicine market with that of the United States, which is presently the largest [8,10]. The case of the United States differs substantially as telemedicine has been extended to insurance fees in telehealth services and outpatient services during the COVID-19 pandemic. The US currently allows medical services to be carried out through emails and SMS. In reality, telemedicine made up nearly 14% of all outpatient services as of 2021, compared to 0.1% before the pandemic [9]. These call for a need to explore the key legal issues and the most significant barriers associated with implementing telemedicine in a pre-COVID-19 healthcare system, and how experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic shaped.Since telemedicine played a critical role in mitigating COVID-19, it is important to consider how South Korea will take guidance from the rapid adoption and implementation of telemedicine in other countries [10]. More importantly, it is important to consider how telemedicine can be effectively positioned as a significant feature of health-care delivery in a post COVID-19 health-care ecosystem. In the case of the United States, it will be important to consider whether telemedicine will continue to be implemented without the earlier state and federal legislative barriers, particularly those around service reimbursement [10,11,12].In spite of telemedicine’s low penetration in South Korea due to legislative barriers, the COVID-19 pandemic brought changes to policymaking triggering the lifting of associated barriers. One of the ways in which the level of improvement can be evaluated is by comparing the current situation of telemedicine-related legislations with other advanced case country scenarios, such as the United States [11,12]. This kind of comparison could help explore regulatory dimensions that explain the differences in telemedicine legislations between the two countries before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Since telehealth is a highly regulated industry that is virtually in its early stage of development, it appears that understanding the development of telemedicine legislation would offer practical insights to assist policymakers in both countries. Therefore, a review of the literature focused on legislation related to telemedicine in South Korea and the United States, a more comprehensive review of academic articles, specifically before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, in this study, the key legal issues and the most significant barriers associated with implementing and adopting telemedicine are discussed. To ensure this, the past and current states of South Korea’s telemedicine legal framework are benchmarked against that of the United States [10,11,12].This study aimed to review the state of telemedicine legislations in the United States and South Korea by undertaking a comparative study of the legislations in pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic era. Across tele-health research, telemedicine has generally been found to have provided high-quality medical services during pandemics or in rural and remote areas [13]. This forms the basis for comparing the state of telemedicine legislations before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.This study extrapolates policy frameworks that will need to be adopted in both South Korea and United States in preparation for a more meaningful adoption and execution of telemedicine in an expanded set of application than those currently defined by the law. The study explores the application of existing and emerging laws that may hinder or facilitate the implementation of telehealth services in a post COVID-19 health-care ecosystem. The study also recommends a set of policy and pragmatic proposals that integrate the recent lessons learned regarding legislative barriers to telemedicine in a pre- and post-COVID-19 health-care ecosystem.

2. Literature Review

- The World Health Organization (WHO) defines telemedicine as a medical practice characterised by providing health services at a distance. In principle, electronic tools are applied in the “diagnosis of treatment and prevention of diseases and injuries, research and evaluation, education of health professionals.” In the United States, the concept was first applied in 1993. A number of changes to the practice and laws governing telemedicine have since been set up [4,14,15,16].In their study of telemedicine practice in the United States and Brazil, Andrade et al. [4] observed that among the most important benefits of telemedicine is its capacity to eliminate or reduce geographical distance. Regarding its usage, Andrade et al. [4] explained that while facsimiles and telephones are still in use, the usage of most recent digital technologies have taken hold, such as smartwatches. Andrade et al. [4] also highlighted a major concern related to telemedicine law pre- and post-Covid-19 as linked to legislative barriers. In effect, the regulatory dimensions of telemedicine entail accreditation, licensing, issues of privacy concerns, payment for services, and liability for medical negligence [14,15,16].The drawbacks attributable to the laws that relate to telemedicine manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic when emphasis was placed on rapid response and a need to overreach certain legal and regulatory provisions. The state of affairs in the US during the pandemic demonstrates the regulatory and legal challenges, and their effects to contain the COVID-19 pandemic using measures like social isolation and quarantine. The COVID-19 pandemic called for a restructuring of the processes, infrastructure, and precedence of the health systems to assist persons suspected as having the disease [4].

3. Method

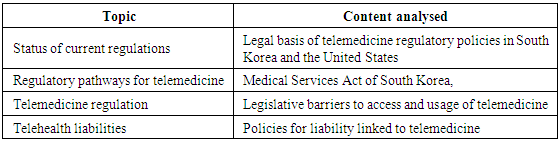

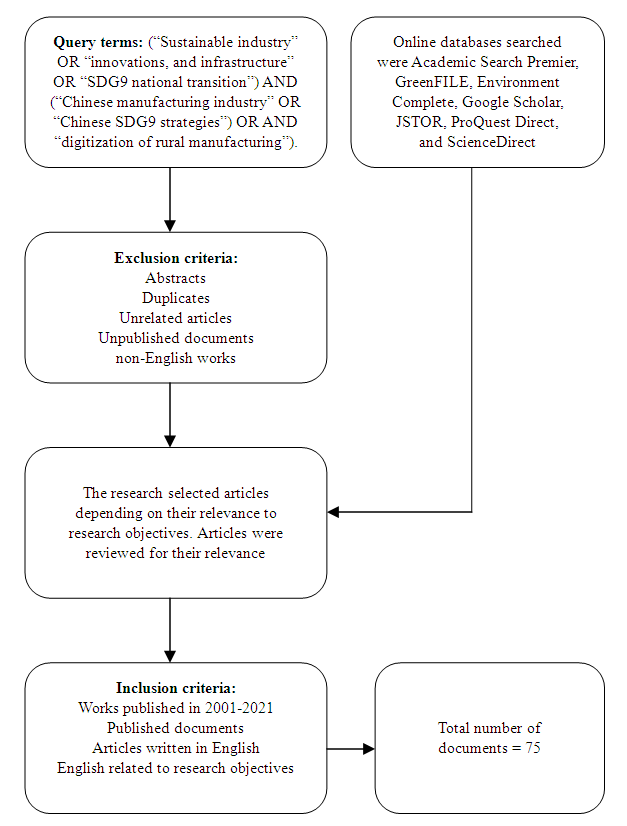

- A review of the literature was carried out for articles that relate to telemedicine. Articles targeted included those published in the period 1991-2021 to reflect the span of 30 years that mark the evolution of telemedicine and associated legislations, and act as the baseline for reviewing pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 healthcare systems. The study entailed review of documents that relate to regulatory and legal frameworks in telemedicine in the United States and South Korea before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. A comprehensive desk research for regulatory and legal frameworks in telemedicine was performed. The process entailed making an online search for regulations, laws, policy briefs, case studies, green papers, reports, and policy recommendations in the period 1990-2021. Supplementary documents also considered for the research included working papers, editorials, reports, reviews, commentaries, and reports.The online databases searched were Ovid MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and PubMed. Additionally, the webpages of a number of professional organisations were reviewed, such a CMS and American Telemedicine Association for relevant data on telemedicine legislation. Keywords applied for search included ‘telehealth legislations South Korea,’ ‘telehealth legislations United States,’ ‘telemedicine COVID-19’, ‘telemedicine COVID-19 regulation South Korea/ United States.’ A search was afterwards made using the Boolean terms and keywords to retrieve related articles published in the target period. The search strategy applied include (“Tele-health” OR “telemedicine” OR “mHealth”) AND (OR “Laws” OR “Legal” OR “Legislation” “Regulation” OR “Regulatory frameworks” AND “South Korea” OR OR “United States”). The process of reviewing and evaluating retrieved documents were based on the subsequent inclusion criteria: They had to represent normative documents published in the period 1990-2021 from regulatory committees, national organisations, journal publications, and professional associations. They also had to provide a description of policies and recommendations on the legal and regulatory frameworks applicable to telemedicine in South Korea and the United States. After the documents were selected, the literature was reviewed to establish their amenableness of the regulation for telemedicine. The reviewed documents were analysed by pointing out their strengths and weaknesses in the context of the amenability of frameworks.A total of 33 articles were reviewed, which were afterwards narrowed down to 52 articles depending on their relevance for analysis. Overall, article selection depended on relevance to research questions and objectives. Inclusion criteria included published documents in the period 1990-2021, which relate to telemedicine legislations in either the United States or South Korea. Articles also had to be published in English. Abstract, duplicates, and unpublished documents were excluded from the search. The details for query, study selection and inclusion criteria applied in this research are illustrated in figure 1 below.

|

| Figure 1. Data collection process |

4. Analysis

- Pre-COVID-19 telemedicine legislations in South KoreaIn effect, telehealth services were initially introduced in 1991 after the launch of “the stage-one telemedicine demonstration project using the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) of Korea Telecomm” [6]. The project was carried out among varied healthcare service providers, such as Seoul National University Hospital and Woori Yeonchon Health Care Center in Gyungi-do. However, legislative barriers impeded the full implementation of telehealth services, despite the changing healthcare environment depending on technological developments advancements [17,18,10]. Eventually, in October 2013, the Korean government proposed a draft/partial amendment of the doctor-patient telemedicine law to the National Assembly [6].The Korean health environment is a factor categorised as favourable for face-to-face consultation leading to a low approval of telemedicine [14,15,16]. As regards accessing medical care, South Korea introduced a welfare-oriented health insurance in 1977. The current national health insurance service was also introduced for everyone in 1989, to provide a comprehensive coverage [19]. As Young and Choi [19] explain, South Korea’s small land area has favoured face-to-face consultation. For instance, the physician distribution in urban and rural is 2.5:1.9 (the sum of physicians per 1,000 people). This is more equitable than the average in OECD countries, including the US, of 4.3:2.8. Physicians are also more favourably in South Korea than the US. Physicians make up 12.1 per 10 square kilometres. In addition, when it comes to demographics, the rate of doctors on duty has grown by nearly twofold, to reach 98% in nearly 2 decades, which is the highest among OECD states. South Korea also has a high quality of medical care, as medical specialists make up around 73% of all physicians, which is much higher than the OECD average of 65% [19].As a result, the South Korean situation experiences a high quality of face-to-face consultation with physicians, eliminating the need for telemedicine. Therefore, in view of the fact that telemedicine principally seeks patients with ready access to high-quality medical care in a country with a highly limited land area lack compulsion to adopt telemedicine [20,21,22,23]. An environment that is favourable to face-to-face consultation has contributed to the prevalent indifference for telehealth care services and low acceptance in South Korea. Indeed, interest in telehealth care services is considered to only have started to take hold in South Korea after the emphasis on travel restrictions and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic [19]. Ultimately, South Korean policymakers determined that there was adequate cause to momentarily ease down the legal restrictions on patient–doctor telemedicine as part of the measures for eliminating the spread of COVID-19.Post-COVID-19 telemedicine legislations in KoreaIn 2019, the Korean government launched a set of measures to promote the bio-healthcare industry, despite failing to deal with the industry’s long-term demand that regulations on telemedicine should be relaxed. Because of legislative restrictions in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic, the government prohibited commercialization of telemedicine products and services in Korea. At present, the situation has not changed [24]. The Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korean Medical Association resisted the idea of legalizing telemedicine because of concerns regarding patient diversion to large hospitals and privacy concerns [25]. This is in contrast to the United States, where the basic policy of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is to make the most of telemedicine as a measure for expanding public health care [24]. South Korea’s telemedicine is restricted. This restriction is set up in the Medical Services Act, which stipulates that “medical service must be provided by a licensed professional in a duly established medical institution” [7]. In spite of the restrictions to telemedicine under the Medical Services Act, the MOHW issued administrative orders that provisionally allowed telemedicine, which had to be valid depending on the persistent of the Covid-19 pandemic. The temporary administrative orders allowed patients to consult physicians over the telephone and to receive prescriptions remotely. Telemedicine service could also be reimbursed under national health insurance system [26,27,14]. However, one area of telehealth services that has not experienced restriction is tele-monitoring through electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring device. The MOHW acknowledges that a specific area that lacks ‘applicable restrictions' is ECG monitoring device. Such restrictions could gradually dissipate because of rapid technological advancements, in light of the growing awareness of the benefits of telemedicine particularly after COVID-19. Jaiyoung and Yu [7] reasoned that with technological advancements, the increasing awareness, and pervasiveness of a variety of wearable devices for monitoring the health of a patient, the restrictions could gradually be relaxed or overreached. On account of the MOHW’s acknowledgement that ECG) monitoring device lack “applicable restrictions,' it is plausible to deduce that monitoring of patients using wearable devices by a healthcare practitioner is allowed. In any case, a review of telehealth documents published during the Covid-19 pandemic reveals that while monitoring of patients using wearable devices may be allowed in Korea, the Medical Services Act should be amended to allow for tele-treatment or telediagnosis [28].Pre-COVID-19 telemedicine legislations in the United StatesIn the United States, federal and state licensing laws restricted the adoption of telemedicine in the pre-COVID-19 healthcare system. Physician licensure laws were initially passed in the early 1900s when health practitioners had to practice their trade at the local level [29]. Consistent with the traditional legislative framework, an out-of-state practitioner was denied the opportunity to evaluate, consult, or treat a patient in any state in which he or she had no full permit to practice medicine. The rationale for this was to enable the state to oversee the physicians practicing in their jurisdictions in order to guarantee quality healthcare [1,8,3]. However, telemedicine seems to have challenged the traditional medical practice model as it facilitates borderless medical practice [29].Licensure policies demand that healthcare service providers should acquire some type of licensure in each state that they seek to operate. A major hindrance to the adoption of telemedicine policies is that they differ from one state to the next. It is inferred from policy documents reviewed that among the most evocative benefits of telemedicine is connecting patients and physicians at a distance [28,29]. Yet, licensure laws and regulations may restrict physicians’ geographic footprints, while simultaneously providing patients with access to physicians with a valid license in the state where they operate. Fundamentally, the Dormant Commerce Clause proposes constitutional standards that can invalidate states laws, which "discriminate against out of state commerce." Since telemedicine is intrinsically economic across many dimensions, including sale of wearable devices and sale of drugs, in-state telemedicine restrictions could be interpreted as having negative economic effects [26,27]. For instance, the Pennsylvanian "extraterritorial license exemption law" is discriminatory against "out-of-state physicians" wishing to attend to patients who are natural residents of the state, yet live or have travelled in neighbouring states. Because of the in-state licensure restrictions, it is difficult for a patient the benefit from telehealth services if their physician is licensed in a different state. Therefore, although the rationale for telemedicine in any healthcare context is to assists as many patients as possible, this would be impeded by licensing requirements for each state [1,8,3].Telemedicine laws can also be interpreted as strongly in violation of the Dormant Commerce Clause, as shown in the case law of Teladoc, Inc. V. Tecas Medical Board. While this case law has no direct reference to in-state license requirements, it demonstrates how the opinion of the courts can be vital. In the case law, Texas Medical Board decided to amend its telemedicine legislations by making it a precondition for physicians to carry out an in-person medical examination or diagnosis of patients prior to providing any telehealth service. In the case law, the claimant accused the Board of violating the Dormant Commerce Clause by means of "discriminating against physicians who are licensed in Texas, but are physically located out of state." The Board, on the other hand, defended itself by arguing that the claimants were unable to identify a claim under the Commerce Clause. However, the court held that the claimant's claims based on the Commerce Clause were adequate. The ruling demonstrates the burdens that physicians like patients go through due to in-state licensure requirements.Post-COVID-19 United StatesThe state and federal government in the United States are yet to amend their legislations to facilitate a full maximization of the benefits of telemedicine by both the patients and the healthcare service providers. A key legal impediment to telemedicine, as identified from documentary evidence of state and federal legislations, is in-state licensure system [15]. The system calls on physicians first seek a license to operate in each state of interest. For this reason, licensing bodies, jurisdictional laws, and regulations in each state restrict the scope of a physician’s practice. Such restrictions have been documented in research as placing a significant burden on physicians who may need to provide telehealth services in other states [15].In the United States, most states have delegated the authority t regulate telemedicine practice, including issuing physician license, to medical boards. Most of these boards are independently set up. Correspondingly, physician licensing regulations diverge across states. Hence, securing a license to operate in multiple states is a major challenge.Before the coronavirus 2019 pandemic, telehealth was familiar although not a prevalent practice. However, increased use of the technology has not inevitably been welcomed by the long-standing rules and regulations that govern the health-care system. Until the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth was basically limited and overtly restrained by indistinct and frequently changing regulations on the reimbursement of doctors and licensure, particularly at state level. State and federal legislatively barriers to the use of telemedicine hindered the launch of the technology to its full potential [15].In South Korea, the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korean Medical Association have both resisted the idea of legalizing telemedicine on account of concerns regarding patient diversion to large hospitals and privacy concerns. This is in contrast to the case with the United States, where the basic policy of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is to make the most of telemedicine as a measure for expanding public health care [24]. There have been calls for state medical boards to waive their in-state license requirements during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, this has substantially depended on whether the COVid-19 pandemics can be categorised an emergency. While the US has suffered from the Covid-19 pandemic, it remains unclear whether providing care to Covid-19 patents is tantamount to an "emergency" [31]. Indeed, the experiences of physician shortage across states during the pandemic have justified the need to ease telemedicine restrictions to help mitigate exposure to coronavirus. Still, like South Korea, the US federal governments also lifted restrictions to telemedicine. This manifested when officials from the federal government provisionally lifted the in-state license requirements, which made it possible for individuals to seek telehealth services from other states.During the COVID-19 pandemic, the US medical system has experienced dramatic transformation in the telehealth industry. Unlike the situation in South Korea where the government temporarily lifted telemedicine restrictions, the US situation was characterised by overhauling of restrictive regulation to allow for the expansion of telehealth (Yonemitsu, 2020). For instance, value-based healthcare, HIPAA-compliant video conferencing, and procedure pay rates were dramatically allowed. As people still needed regular patient care despite the need for social distancing to stop the spread of the virus, the US significantly changed bureaucratic red tape to make it possible for more people to use telemedicine [31].The enactment of a number of federal legislations has set the states on the course to ease their respective telemedicine restrictions. The passage of the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act on March 6, 2020 can be determined to have eased telehealth restrictions that are in existence in the United States. It basically lifted penalties that healthcare providers could be exposed to for HIPAA privacy violations that happened in the process of providing telehealth care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to this legislation, healthcare providers could have been held legally responsible in cases where their HIPAA-compliant video conferencing software had a privacy breach. Such requirements deterred many healthcare providers from providing telemedicine. On March 27, 2020, the CARES Act was amended to increase funding and flexibility for healthcare service providers, who provided telemedicine to their clients.

5. Discussion

- From reviewing the state of telemedicine legislations in the United States and South Korea in the pre- and post-COVID-19 healthcare systems, it is ascertained that despite the legislative barriers in both countries, telemedicine provided high-quality medical services during pandemics or in rural and remote areas. In spite of telemedicine’s low penetration in South Korea due to legislative barriers, the COVID-19 pandemic was found to have brought changes to policymaking triggering the lifting of associated barriers. One way in which the level of legislative improvement can be evaluated is by comparing South Korea’s telemedicine-related legislations with those of the United States. There are significant differences in telemedicine legislations between the two countries before and after the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2,3,4]. Like South Korea, the US federal governments also lifted restrictions to telemedicine. This manifested when officials from the federal government provisionally lifted the in-state license requirements, which made it possible for individuals to seek telehealth services from other states. However, in the situations between the two countries differed substantially in the pre-COVID-19 healthcare system. South Korea completely banned telemedicine, which barred telemedicine practice across the country. On the other hand, a key legal impediment to telemedicine in the United States is tied to the existence of in-state licensure system and federal reimbursement policies that focus on Medicare.Telemedicine appears to still have a long way to eventually have a meaningful and broad impact in both the United States and South Korea due to these legislative barriers, some of which were only waived during the COVID-19 pandemic. As indicated by the history of telehealth services and the dramatic evolution of existing legislations in both countries, much still needs to be done. Towards this extent, it could indeed be argued that among the most elemental factors that can accelerate telemedicine expansion in the US and South Korea would be to develop robust legal standards [27,28,29]. Robust legal standards would cut down the extent of uncertainty and guarantee many advantages, such as data security for using telemedicine in the two countries, regulating private and public reimbursements in the United States, and speeding up the processes of telemedicine regulations regardless of geographic delimitations. While the legal standards would not necessarily address all concerns, they could remove all the barriers and serve as a robust underpinning for fostering telehealth in South Korea. Comparing the situation in South Korea with the evolution of telemedicine legislations in the United States does, however, not offer a comprehensive blueprint given that the two countries economic situations and health system conditions differ substantially [1,2,3,4]. In any case, South Korea still needs to learn from the legislative evolution in the US before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as any other country where telemedicine has advanced.A number of observations were made with respect to the policy frameworks that will need to be adopted in both South Korea and United States in preparation for a more meaningful adoption and execution of telemedicine in an expanded set of application than those currently defined by the law. There is a need to build regulatory flexibility into telemedicine to cater to demands from a range of cases. Focus should be directed towards data security and privacy protection in telehealth services. While the right legislative frameworks are clearly the keystones of a detailed telemedicine policy in both the US and South Korea, the most decisive issue that needs to be solved is intervention of technology in the doctor–patient relationships. A number of legitimate issues have been identified particularly in the case of the data security and privacy issues in the United States, and the usage of the best possible evidence accessible for diagnosis and treatment [1,2,3,4]. As also observed, telemedicine is still in the early stage of development in South Korea. Therefore, these concerns and related legislations still need to be explored in detail in future.Although the legislative changes in the US are intensely dramatic, the transition to telemedicine has been more remarkable in Korea. On February 22, 2020, South Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare declared that, consultations and prescriptions can temporarily be provided to patients remotely, through the telephone at the discretion of the physician and when the physician can guarantee safety. The legislative shift in South Korea is even more radical since compared to the US, it completely banned telemedicine and did not have viable telehealth structures in place. Yet, in both countries, the legislative shifts were swift and in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The shifts also changed how the public and medical practitioners viewed telemedicine [2,3,4].Still, concerns over privacy are intense. Finding HIPAA-compliant video conferencing platforms is not clear-cut and healthcare service providers could use platforms like Facetime that lack HIPAA-compliant chats or video calls. The existence and use of such platforms demonstrates that there is a need for a more specific legislation that defined a physician’s liability or responsibility on issues surrounding sharing of client data. This differs with the situation in South Korea focus should be placed on building infrastructure and a practicable system while at the same time protecting patients’ privacy rights. South Korea is less advanced in terms of implementing telemedicine since legal and regulatory restrictions prohibit distant medical care provision to patients [33]. The need for telemedicine was only brought to the fore of policy discourse during the Covid-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, laws and regulations remained intact [33].Given that the healthcare sector consists of a number of economic sub-sectors, US Congress should consider regulating the telemedicine industry pursuant to the Commerce Clause. Even so, the commerce power of the federal government is, in theory, concurrent with that of the state, The Supreme Court set up the "Dormant Commerce Clause" as an element of such a concurrent power dynamic between the state and the federal government. The Dormant Commerce Clause requires that any state law that imposes unnecessary burden on interstate commerce is unconstitutional.In the United States, one of the legislative barriers is the reimbursement system. As federal reimbursement policies focus on Medicare, their interpretation has tended to be narrow. Reimbursements also impose limitations on where telehealth services should occur [14]. In addition, each state defines different Medicaid policies, and in turn creates sets of different telemedicine laws and regulations nationally. From the year 2000, states started enacting legislations targeted at encouraging reimbursement of telehealth-delivered services by private payers [14]. Yet, telehealth laws seem to have been written in a manner that they bring parity in both payment and coverage. Although payment parity functioned as a strong incentive for adoption of telemedicine platforms by more healthcare service providers, an implementation of equal payment also has a potential to undercut the cost-effectiveness of telemedicine [14]. In this way, it can be ascertained by legislative directives do actually affect the delivery of telemedicine initiatives, mainly because its meaningful adoption depends on statutory language. Even as a full implementation of telemedicine under state and federal policies before the COVID-19 pandemic needs to be priority, it appears that newer policies after the pandemic will need to address emerging concerns that relate to reimbursement policies and licensing laws [14].

6. Conclusions

- A major concern over telemedicine law in the pre- and post-Covid-19 healthcare system can largely be linked to legislative barriers. In spite of the legislative barriers in both South Korea and the United States, telemedicine provided high-quality medical services during pandemics or in rural and remote areas. In spite of telemedicine’s low penetration in South Korea due to legislative barriers, the COVID-19 pandemic was found to have brought changes to policymaking triggering the lifting of associated barriers. One way in which the level of legislative improvement can be evaluated is by comparing South Korea’s telemedicine-related legislations with those of the United States. There are significant differences in telemedicine legislations between the two countries before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Like South Korea, the US federal governments also lifted restrictions to telemedicine. This manifested when officials from the federal government provisionally lifted the in-state license requirements, which made it possible for individuals to seek telehealth services from other states. However, in the situations between the two countries differed substantially in the pre-COVID-19 healthcare system. South Korea completely banned telemedicine, which barred telemedicine practice across the country. On the other hand, a key legal impediment to telemedicine in the United States is tied to the existence of in-state licensure system and federal reimbursement policies that focus on Medicare.

7. Recommendations

- For both South Korea and the United States, there is a need to build regulatory flexibility into telemedicine to cater to demands from a range of cases. The existing regulations, specifically those waived during the COVID-19 pandemic should be evaluated prior to reverting to legacy regulations. As established in this review, large gaps did exist when it comes to consistency in the implementation of telemedicine prior to the pandemic and would persist unless amendments are made to legislations at the federal and state level. For instance, by reverting to pre-COVID-19 laws and regulations, the US will be negating the lessons learned during the pandemic under streamlined legislative frameworks.Among other elemental factors that can accelerate telemedicine expansion in the US and South Korea would be to develop robust legal standards. These would cut down the extent of uncertainty and guarantee many advantages, such as data security for using telemedicine in the two countries, regulating private and public reimbursements in the United States, and speeding up the processes of telemedicine regulations regardless of geographic delimitations. Focus should, therefore, also be directed towards data security and privacy protection in telehealth services. In both South Korea and the United States, emerging technologies like artificial intelligence have the potential to spread out access to telehealth services without adversely affecting patient privacy [1,2]. For the US, for instance, it is significant to tie current policy discussions on the necessity for federal privacy legislations with telehealth services. Discussions on the significance of encryption are likewise imperative, particularly as more people take part in personal conversations with physicians over internet-enabled mobile devices. Outwardly, telemedicine practice is likely to generate large amounts of personal data that need to protection. In the US, HIPAA privacy protections will still need to apply to telehealth services. Data security should also be accorded primacy in ensuring the protection of personal health data. In the case with the United States, there would be a need to empower states to abandon parity models to ease the cost of telemedicine. To encourage the adoption of telemedicine among health service providers, each individual state should abandon parity models for reimbursement, as they have hampered the ability of healthcare service providers to adopt a wide variety of technologies as eligible services. Parity laws also provide authorization for comparable of reimbursements of a “visit” that occurs through telemedicine to those that a medical practitioner makes individually. Since the cost of delivering telehealth services is lower, they should be treated in the same way as well as coordinated among states to facilitate their broad acceptance. In principle, as telemedicine was caused to experience parity during the COVID-19 pandemic, medical interventions were dictated by time, particularly when reasonable models for reimbursement were lacking.

8. Research Limitations

- The study has a number of limitations. First, the research was carried out as a narrative review instead of a systematic review of the literature. Technically, a systematic review tends to present a more comprehensive and rigorous approach to reviewing the literature. Therefore, using a narrative review means that some significant studies may not have been included in the research. Future studies should consider using a quantitative research approach to corroborate findings in this research.Comparing the evolution of telemedicine legislations in South Korea and the United States does, however, not offer a comprehensive outline given that the two countries economic situations and health system conditions differ substantially. In any case, future research could explore how South Korea still could learn from the legislative evolution in the greater North America and Europe before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as any other country where telemedicine has advanced.

9. Practical and Theoretical Implications

- Findings in this research provide insights into how telemedicine legislations could be amended to facilitate a full maximization of the benefits of telemedicine by both the patients and the healthcare service providers. The results of the study also opened conversations on the need to allow post-COVID-19 healthcare systems to circumvent long-established legal and regulatory provisions to improve access to care.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML