-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Bioinformatics Research

p-ISSN: 2167-6992 e-ISSN: 2167-6976

2021; 11(1): 38-47

doi:10.5923/j.bioinformatics.20211101.03

Received: Jun. 21, 2021; Accepted: Jul. 7, 2021; Published: Jul. 15, 2021

Costs and Benefits of Telemedicine During the COVID Pandemic and Future Legislative Implications in South Korea

Choi Yong-Jeon

Dept. of Law and Public Service, Daejin University, Hoguk-ro, Pocheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Correspondence to: Choi Yong-Jeon, Dept. of Law and Public Service, Daejin University, Hoguk-ro, Pocheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Aim and objectives: This study aimed to assess the implications of telemedicine law on health care practice, particularly how it has affected clinicians’ practice during the Covid-19 pandemic. To ensure this, it investigated the costs and benefits of telemedicine by healthcare practitioners in South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to provide insights as to whether telemedicine continue being regulated in South Korea’s post-pandemic healthcare system. To assess the implications of South Korean telemedicine ban on health care practice, the survey looked at whether telemedicine leads to improved cost-saving and the extent to which telemedicine contributes to hospital avoidance. Method: A quantiative web-based survey was distributed to health practitioners in South Korea’s Daegu Haany University Korean Medicine Hospital. Analysis of data was performed on the basis of parametric statistics and frequency percentages. Findings and Results: The benefits of telemedicine in South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic can be categorised into three: cost, access, and outcomes. While telemedicine does not seem to have replaced medical examination during Covid-19 pandemic in the context of South Korea’s healthcare system, it helped curtail the spread of the virus. It also avoided the need for patients to visit hospitals. Findings also suggested that telemedicine was useful for caring for patient undergoing palliative treatment or for management of chronic disorders during the pandemic by reducing hospital visitation. Conclusion and recommendations: There is an upward acceptance of remote consultations to improve the ease of use of health care for underserved communities. Healthcare providers suggest a need to lift the legislative restrictions on telemedicine for the country’s post-COVID-19 healthcare systems.

Keywords: Telemedicine South Korea, Telemedicine legislations, Telemedicine costs, Telemedicine benefits

Cite this paper: Choi Yong-Jeon, Costs and Benefits of Telemedicine During the COVID Pandemic and Future Legislative Implications in South Korea, American Journal of Bioinformatics Research, Vol. 11 No. 1, 2021, pp. 38-47. doi: 10.5923/j.bioinformatics.20211101.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Study backgroundThe COVID-19 pandemic heralded significant global health crisis and sequentially provided global health systems with an impetus to use telemedicine in ambulatory care settings (Galiero et al., 2020; Kima et al. 2020; Kwon & Lee, 2020; Yonhap, 2020). There are assertions in recent body of digital health technologies research that telemedicine policies passed during the pandemic may not persist beyond the pandemic (GlobalData, 2020). Even so, there continues to be an understanding among primary healthcare providers that the benefits of telemedicine services may justify the need for more favourable policies, particular in countries that impose restrictions on telehealth services (OECD, 2021). South Korea is among the few countries that contained the COVID-19 pandemic without resorting to stringent measures like the imposition of inbound and outbound travel restrictions (Galiero et al., 2020; Kima et al. 2020; Kwon & Lee, 2020). Accounts of evidence from healthcare service providers show that this milestone was attributable to the usage of technology to enable extensive testing and the relaxation of telemedicine regulations in the country (Benger et al., 2004; Dimmick et al., 2000). The COVID-19 pandemic led the government to ease telemedicine regulations and in the process opened up the digital health sector for growth. A sectoral research by GlobalData indicates that at least 111 telehealth business transactions valued at US$2.8 billion were executed in the period 2019-2020 (GlobalData, 2020). This indicates that the role of digital health in making it possible to control COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea and how the pandemic triggered interest and investment in telemedicine. In South Korea, the Association of Korean Medicine formed the COVID-19 telemedicine centre of Korean medicine (KM), which provided telemedicine services during the pandemic. One month after KM was established, close to 20% of COVID-19 patients had been attended to by the centre (Kima et al. 2020). The spread of infectious disease was also curtailed through early detection and isolation. South Korea was among the earliest countries that were hardest hit by COVID-19 because of a mass infection following an incident where an infected person visited a church in Daegu-Gyeongbuk, leading to an explosion of infections. The explosive infection led to an overstretching of medical resources. The Korean government responded by temporarily lifting the ban on telemedicine – or medical telephone counselling. The Association of Korean Medicine established a telemedicine center in Daegu on March 9, 2020 (Kima et al. 2020). The centre used herbal medicine purposely for alleviating COVID-19 symptoms and providing patients with meditation to improve their mental health. Physicians under the Korean Medicine performed prescription of herbal medicines based on defined protocols and research-based data on COVID-19.Problem Statement and research rationaleWhile telemedicine is banned in South Korea, legislative restrictions were temporarily lifted consistent with the social distancing measures and travel restriction protocols set up globally to help curtail the spread of coronavirus (Kima et al. 2020; Kwon & Lee, 2020; Yonhap, 2020). South Korea, with its diverse world-class technology sector, had to explore the potential of digital health during a period when patients hesitated to visit hospitals fear of contracting the virus (Bloomberg, 2020).Telemedicine has, on the other hand, demonstrated a remarkable growth potential outside South Korea. According to GlobalData (2020), the telemedicine sector in Asia-Pacific is projected to grow from $8.5 billion in 2020 to approximately $22.5 billion by 2025. Since 2013, the government could only allow restricted telemedicine on a trial basis in spite of a strong opposition from healthcare practitioners who question its safety. While telemedicine is largely credited for making it possible to control the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea, some stakeholders like the Korean Medical Association (KMA) are strongly in opposition of telemedicine (Yonhap, 2020). In South Korea, the projections are still in doubt as the temporary decrees that lifted telemedicine are expected to be lifted in South Korea’s post-COVID-19 healthcare systems.While there is a significant body of research showing a growing acceptance of telemedicine in South Korea, there is still a general reluctance by the KMA to support its full implementation (Bloomberg, 2020; Yonhap, 2020). Indeed, there are assertions in recent body of digital health technologies research that telemedicine policies passed during the pandemic may not persist beyond the pandemic (Galiero et al., 2020; Harno et al., 2018; Kwon & Lee, 2020).Regulations in the country would make it difficult to confer with a physician abroad, in spite of an upward acceptance of remote consultations to improve the ease of use of health care for underserved South Korean communities (Kwon & Lee, 2020; Yonhap, 2020). This current state of affairs provides a strong rationale to investigate the costs and benefits of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. While proponents of telemedicine project health care cost savings in a post-COVID-19 healthcare system in South Korea, there is a paucity of research evidence that supports this view. Therefore, vital questions that relate to cost and sustainability in the South Korean context will need to be unanswered. Overall, these call for a need to assess the implications of telemedicine law on health care practice, particularly how it has affected clinical decision-making Pre-COVID and during the Covid-19 pandemic.Aims and objectivesThe aim of this survey is to investigate the costs and benefits of telemedicine by healthcare practitioners in South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to provide insights as to whether telemedicine continue being regulated in South Korea’s post-pandemic healthcare system.To assess the implications of South Korean telemedicine ban on health care practice, the research objectives for this study included:• To investigate whether telemedicine leads to improved cost-saving?• To determine the extent to which telemedicine contributes to hospital avoidance.• To investigate the extent of acceptance of telemedicine among primary health providers.• To investigate whether telemedicine improves care for patient undergoing palliative treatment and management of chronic disorders during the pandemic?

2. Literature Review

- Telemedicine refers to “the delivery of healthcare services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health-care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health-care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities” (WHO 2009). On the other hand, the term telehealth refers to the delivery of health care services through ICT to bridge the geographic gap between healthcare practitioners and patients. Research has showed that telehealth has a potential to cut costs by reducing travel, shortening interactions, contributing to economies of scale (Snoswell et al, 2020). Telemedicine has recently become more meaningful for providing healthcare service in rural areas and managing chronic diseases. The COVID-19 pandemic also led to the deployment of telemedicine in areas that had initially banned it, thus showing its potential to support traditional medicine in scenarios where human contact is discouraged. Across telehealth research, the potential for telemedicine to cut the cost of health care seems to be the most dominant reason that motivates healthcare service providers to adopt technology, followed by the necessity to make healthcare more accessible to patients (Galiero et al., 2020; Harno et al., 2018; Kwon & Lee, 2020; Snoswell et al, 2020). In spite of this, demonstrated cost-effectiveness of telemedicine may be unattainable during a pandemic due to legislative barriers and budget constraints.A number of evidence-based scenarios have recently been analysed showing the potential expediency of telemedicine during epidemics. Health sector research on the effects of telemedicine has generally identified three sets of benefits: in terms of cost, improved access, and outcomes (Dimmick et al., 2000; Harno et al., 2018; Kwon & Lee, 2020). For instance, Lurie and Carr (2018) examined the role of telehealth during disasters and found that it can lead to improved healthcare service. They established that telehealth is particularly useful for attending to asymptomatic people in an epidemic area because of its “home-based” management that exposes populations to fewer risks for spread of infections. In addition, positive asymptomatic subjects can be monitored using intervallic phone and teleconsulting. Galiero et al. (2020) also found evidence showing that telemedicine can provide practical measures for taking care of individuals either in nosocomial isolation. For this type of scenario, telehealth services provide sufficient safety to both caregivers and clinicians, as it limits a direct contact with the infected persons (Lurie and Carr, 2018).Telemonitoring has over the years been found to be crucial for managing chronic conditions (Lurie and Carr, 2018; WHO, 2009). Of the chronic diseases, Galiero et al. (2020) established that cardiovascular diseases predominantly rationalize a necessity for constant monitoring, which may increase the exposure to COVID-19 infections for both clinicians and patients (Lakkireddy et al., 2020). On this premise, the use of telemonitoring was extended outside emergency situations, to other activities like observing a rapid enhancement of e-health technologies during pandemics. For instance, electrophysiologists in the United States began to convert a majority of clinical visits to telemonitoring and cardiac implantable monitoring devices whenever necessary (Driggin et al., 2020).Across telemedicine research, there are strong indications that among the benefits of telemedicine are telemonitoring or remote monitoring of patients. Remote monitoring has been found to be effective for monitoring chronic diseases. It involves an ongoing in-home recording of a patient’s target biometric readings (Benger et al., 2004; Dimmick et al., 2000; Galiero et al, 2020; Harno et al., 2018; Kwon & Lee, 2020). Research on the effects of remote monitoring usage on healthcare provision is mixed. In a case control study in France, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, findings suggested a reduction on cost of hospitalization as a result of remote monitoring (Steventon et al., 2012; Woods et al., 2013). In the United Kingdom, a study on remote monitoring showed a reduction in the admission of patients with chronic diseases, such as diabetes (Steventon et al., 2012). In the case of the United States, findings suggested that whenever the vital signs of patients were conveyed to a nurse for reviewing and intervention, there could be a dramatic reduction in the numbers of acute care hospitalization (Woods et al., 2013).When it comes to the case with Australia, one study indicated that healthcare service providers that used remote monitoring could foretell and circumvent 53% of hospital admissions by carrying out low-cost interventions efficiently (Celler et al., 2016). It was also found to lessen the presentation of patients to hospitals as well as to prolong their length of stay after their admission. This may result from the self-assurance that remote monitoring provides to medical practitioners so that once a patient is discharged, the patient would still be monitored and observed in case their situation worsens (Dimmick et al., 2000; Galiero et al. (2020; Harno et al., 2018; Kwon & Lee, 2020). A study of the effect of telemonitoring on patient outcomes in Belgium found that high-risk mothers could be monitored by hospitals in their homes (Takahashi et al., 2012). Still, an economic analysis of telemonitoring does not convincingly indicate cost savings. While there are studies that have reported considerable cost savings, there are some that reported very minimal savings. An economic analysis performed by Lew et al. (2019) in the US health sector established that telemonitoring for certain groups of patients reduced admission costs very minimally to US$10,678, from US $10,835. A related study also reported that telemonitoring increased costs due to increased costs of amortization of equipment (Ehlert & Oberschachtsiek, 2019). Health sector research on the effects of telemedicine in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic identified three sets of benefits: in terms of cost, improved access, and outcomes. In Singapore, telemedicine-enabled system improved triage and improved patient care in a rather fragmented health-care ecosystem. In Japan, it increased patient-doctor consultation by 15-fold (Bloomberg (2020).Telemedicine has also been found to increase the productivity of medical practitioners, and by this means intensifying the number of patients who can access health service. In case of fixed costs, this may reduce marginal costs per patient. Telemedicine can as well facilitate a medical practitioner to transfer travel time to clinical time, and in so doing increasing productivity (Snoswell et al, 2020). Yet, it has also been observed that when medical practitioners do not have to travel to provide care, alternating video consultations with in-person consultations may substantially affect consultation time and the resulting cost savings and productivity (Harno et al., 2018; Kwon & Lee, 2020). Additionally, an increase in administrative costs for scheduling video consultations has a potential to counteract the benefits of telemedicine. A growing body of research has also demonstrated that when telemedicine eliminates or reduces medical practitioners’ travel time since service delivery happens via videoconference, their productivity improves as they can attend to more patients within the same time frame (Benger et al., 2004; Galiero et al., 2020; Harno et al., 2018; Kwon & Lee, 2020; Snoswell et al, 2020). A study of a telehealth program implemented in the United States via a videoconference telehealth model to substitute home visits established that caseload capacity for clinicians grew by more than two-fold in around 14 months. As a result, the number of driving minutes that the clinicians saved was estimated to have clocked 43,560 at the end of 14 months (Dimmick et al., 2000). In the same way, an economic assessment of The Northern Health Authority in Canada also established that when telehealth sessions were made to replace in-person sessions, it led to cost savings of nearly US$49,584.14, which could have otherwise been used to cover the cost of travel.Healthcare service providers that substitute in-person consultations with brief video consultation realised an improved capacity to attend to more patients in the same time frame (Benger et al., 2004; Dimmick et al., 2000; Yonhap, 2020). Studies that sought to compare videoconference consultation time with in-person consultation time have tended to report dissimilar results. One study found that teleconsultations could take more time in comparison to in-person consultations in specific cases where physicians had to assess an injury or a symptom by video rather than in person (Benger et al., 2004). Other sets of studies showed that teleconsultations were evenly as time efficient as in-person consultations, particularly in orthopaedics, prostate cancer and pulmonary medicine (Buvik et al., 2016). On the other hand, some evidence also indicate that teleconsultations tend to be more time efficient, as indicated in of telehealth services in dermatology care in Norway (Nordal et al., 2001).Healthcare service providers that substitute in-person consultations with asynchronous or virtual consultations experience improved productivity, which may tend to increase when more patients can be managed concurrently (Blount & Gloet, 2015). Asynchronous consultations occur when a clinician and a patient do not operate on the same time zone. They, as a result, embody a mechanism through which a health system’s productivity can be improved. A typical situation is where a clinician can review clinical notes for a number of patients faster and more efficiently than it would take them to individually examine all patients (Harno et al., 2000). This tends to be the case for dermatology teleconsultations, whereby either a primary care giver or patient has to send dermoscopic images for review (Snoswell et al., 2016). Essentially, consultations tend to be faster whenever they are asynchronous. For instance, some studies have established that an asynchronous dermatology consultation is likely take an average of 4 minutes, which is nearly 10% the time it would take with in-person consultation (Loane et al., 2000). In turn, this can increase the system throughput, leading to an optimized prioritization of patients. Likewise, a case-control research demonstrated that medical practitioners who applied a web-based messaging platform for purposes of managing patients showed increased productivity by at least 10%, in comparison to those undertaken through an in-person consultation. Ultimately, increased productivity led to an increase in the number of patients attended to by 2.54 (Liederman et al., 2005).Research also suggests that telemedicine can facilitate hospital avoidance, which has a potential to cut costs, particularly in reducing emergency department presentations. In their study of the effects of telehealth on Emergency Medical Services in Houston, United States, Comín-Colet et al. (2016) observed a tendency of hospitals to implement a system where physicians could carry videoconferencing with patients prior to dispatching an ambulance to carry patients to the ED. Whenever necessary; patients could be referred to primary care. They found that transportation to the ED could be reduced by up to 50% (Comín-Colet et al., 2016). Gillespie et al. (2016) also investigated the effects of telehealth on residential aged care and reported a reduction in ED presentations by 28%. Both studies did not quantify the effects of telehealth on cost savings.A related review showed that teletriage potentially reduces a considerable number of needless outpatient appointments with medical specialists. Caffery et al. (2016) established that when it comes to appointments with dermatology, teletriage could prevent in-person appointments by as much as 88%. In which case, telemedicine seems to potentially lessen secondary health care usage. Conversely, while it appears that a large number of studies reveal a decline in secondary care whenever telehealth is involved, not many studies have quantified cost savings for patients (Harno et al., 2018; Kwon & Lee, 2020).. Studies that have undertaken analysis of costs seem to have failed to investigate total costs of telehealth interventions. Rather, they have only attempted to make a comparison of costs linked to the usage of direct health care. A more reliable investigation could include looking at costs of programs, and equipment amortization. A seemingly predominant reason for costs reduction was in situations wheer health system had to fund travel of other a clinician or a patient. There are also indications that telehealth potentially increases costs as much as it improve cares.

3. Materials and Methods

- This study is a cross-sectional web-based questionnaire study carried out with primary healthcare providers at Daegu Haany University Korean Medicine Hospital, as the research participants. The research was undertaken in a single phase, whereby primary healthcare providers from different departments of the hospital were given a link to a web-based questionnaire embedded on SurveyMonkey.com. A web-survey was used, as it was appropriate for assessing physicians’ perceptions of telemedicine without necessary meeting them in person. This method of data collection through an online questionnaire was consistent with the social distancing protocols put forth by the Telemedicine Center.A total of 52 primary healthcare providers were asked 9 questions. The questioned mainly pertained to perceptions regarding the costs and benefits of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. OECD (2021) defines primary care “as care for non-emergency care, care for chronic condition and gate keeping for the secondary care” (p.1). An efficient primary care responds sufficiently to a considerable number of health care demands, avert needless hospital admissions, cut needless health care costs and improve patient outcomes (Ock et al., 2014). While Korea lacks a robust primary care system, such as Family Doctors or General Practitioners sector, compared to other OECD countries, patients have greater access to speciality care in general hospitals and community. Patients have access to initial consultation without a precondition to present a referral letter, with the exception of state-owned tertiary hospitals (OECD, 2021). The easy access to physicians at the community level has led to a high frequency of medical consultations. This is attributed to Korea’s current status as having the lowest ratio of physicians among OECD countries (OECD, 2021). In 2017, the rate of physician “consultation was 16.6 times a year, compared to the OECD average of 6.8 in 2017 (OECD, 2021, p.1). Patients are provided with primary-level care at public health care by family medicine doctors or other specialists.Prior to using the questionnaires to collect data, the questionnaires went through a pretesting process to check for their reliability and validity. Cronbach's alpha was used to determine their reliability. The reliability score was good (alpha = 0.849). Paired t-test was applied to validate the questionnaire, whereby P value was observed to be not significant (P > 0.856). This validated the questionnaire. The study took 4 months - from February to May 2021. A convenience sampling technique was used to select 52 primary healthcare providers from Daegu Haany University Korean Medicine Hospital. The inclusion criteria included primary healthcare providers who have used telehealth services and provided their written informed consent to participate in the research. For purpose of statistical analysis, data collected using online questionnaires had to be coded and analysed using Data Analysis and Statistical Software (STATA). Analysis of data was performed on the basis of parametric statistics and frequency percentages.

4. Results

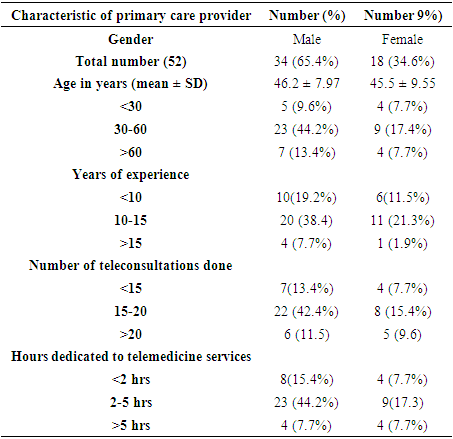

- Daegu Haany University Korean Medicine Hospital provides infrastructure for implementation of telemedicine services. The Telemedicine Center of Korean Medicine at Daegu Haany University Korean Medicine Hospital was of interest to the research, as it was constructively involved in deploying telemedicine to curtail the spread of coronavirus (Kwon & Lee, 2020). Physicians at the telemedicine centre used herbal medicine to relieve COVID-19 symptoms. They also used telemedicine to provide mindfulness meditation to improve COVID-19 patients’ mental health. COVID-19 patients could consult physicians at the telemedicine center through telephone. The physicians would then prescribe herbal medicine, such as Huo-Xiang-Zhengqi-San, Yin-Qiao-San and Qing-Fei-Pai-Du-Tang (Kwon & Lee, 2020). The prescribed medicine would then be delivered directly to the patients at their places of residence through primary healthcare providers or volunteers. The physicians at the hospitals had to make follow up phone calls at an interval of three days to monitor the symptoms. Follow up calls were made to patients every 3 days to check for changes in symptoms. The physicians would assess baseline diseases of the patients such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer before determining for likely COVID-19 symptoms. A total of 52 primary healthcare providers participated in the questionnaire survey. All participants had provided telemedicine services to patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, using such tools as telephones, emails, and teleconferencing. Consultations varied from patients seeking advice on management and treatment of headaches to COVID-19.

|

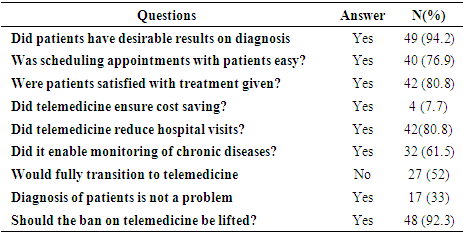

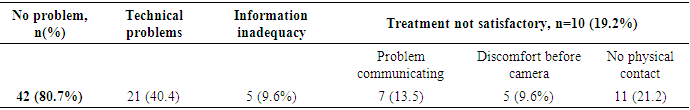

About 88% of the primary health providers surveyed stated that offering treatment through telemedicine was both practicable and convenient. However, only 7.7% of the participants thought that treatment through telemedicine was more expensive than in-patient consultation, despite being convenient.Overall, 40.4% primary health providers stated that the problems associated with telemedicine were mainly technical in nature. 30.8% of the participants felt that teleconferencing is inconvenient to them as they did not feel at ease facing and speaking to a camera, than handling an in-person consultation.

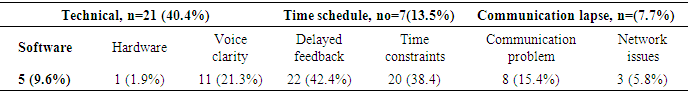

About 88% of the primary health providers surveyed stated that offering treatment through telemedicine was both practicable and convenient. However, only 7.7% of the participants thought that treatment through telemedicine was more expensive than in-patient consultation, despite being convenient.Overall, 40.4% primary health providers stated that the problems associated with telemedicine were mainly technical in nature. 30.8% of the participants felt that teleconferencing is inconvenient to them as they did not feel at ease facing and speaking to a camera, than handling an in-person consultation. In teleconsultations, the primary health providers experienced problems with associated with technical hitches (40.4%), communication lapse (7.7%), and scheduling consultations 13.5%.

In teleconsultations, the primary health providers experienced problems with associated with technical hitches (40.4%), communication lapse (7.7%), and scheduling consultations 13.5%. It was also found that telemedicine can facilitate hospital avoidance, which has a potential to cut costs, particularly as this reduced emergency department presentations. Of the participants surveyed, 80.8% stated that telemedicine reduced hospital visits during the COVId-19 pandemic.There was also a strong indication that telemedicine facilitated effective for monitoring chronic diseases during the pandemic, as 61.5% of the participants stated that they had found it useful for this purpose. In any case, current research data also indicated that participants did face challenges with diagnosis whenever they used teleconsulting to engage with patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the participants, 33% agreed to have faced challenges with diagnosis using teleconsulting. In addition, 52% of the participants admitted to be unwilling to fully transition to telemedicine.Telemedicine mitigates the spread of viral infections while simultaneously making it possible for patient to continue their diagnostic-therapeutic process. Of the participants surveyed, 78% acknowledged the usefulness of telemedicine in this regard.

It was also found that telemedicine can facilitate hospital avoidance, which has a potential to cut costs, particularly as this reduced emergency department presentations. Of the participants surveyed, 80.8% stated that telemedicine reduced hospital visits during the COVId-19 pandemic.There was also a strong indication that telemedicine facilitated effective for monitoring chronic diseases during the pandemic, as 61.5% of the participants stated that they had found it useful for this purpose. In any case, current research data also indicated that participants did face challenges with diagnosis whenever they used teleconsulting to engage with patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the participants, 33% agreed to have faced challenges with diagnosis using teleconsulting. In addition, 52% of the participants admitted to be unwilling to fully transition to telemedicine.Telemedicine mitigates the spread of viral infections while simultaneously making it possible for patient to continue their diagnostic-therapeutic process. Of the participants surveyed, 78% acknowledged the usefulness of telemedicine in this regard.5. Discussion

- The questions framed in this survey were relevant for investigating the costs and benefits of telemedicine by healthcare practitioners in South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to providing insights into whether telemedicine should continue to be regulated or not in South Korea’s post-pandemic healthcare system. The survey targeted primary healthcare providers or physicians at the Telemedicine Center of Korean Medicine at Daegu Haany University Korean Medicine Hospital who were either directly or indirectly tele-consulted by patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.The aim of this survey is to investigate the costs and benefits of telemedicine by healthcare practitioners in South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to provide insights as to whether telemedicine continue being regulated in South Korea’s post-pandemic healthcare system. To assess the implications of South Korean telemedicine ban on health care practice, the survey investigated whether telemedicine leads to improved cost-saving and the extent to which telemedicine contributes to hospital avoidance. Likewise, focus was placed on investigating the extent of acceptance of telemedicine among primary health providers, and whether telemedicine improves care for patient undergoing palliative treatment and management of chronic disorders during the pandemic.Findings suggest that primary healthcare providers support the idea that current legislations that ban or restrict telemedicine practice in South Korea should be lifted. Of those surveyed, 92.3% stated that legislative restrictions on telemedicine should be lifted. This seems to be attributable to their direct experience with the benefits of telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic after the government temporarily eased telemedicine regulations and in the process opened up the digital health sector for growth. This indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic triggered interest and investment in telemedicine in South Korea. The participants’ perception that telemedicine regulations should be eased in a post-COVID-19 healthcare system seems to be directly tied to the benefits of telemedicine, as they directly witnessed in their practice during the pandemic. Results show that benefits of telemedicine far outweighed the costs. While telemedicine does not seem to have replaced medical examination during Covid-19 pandemic in the context of South Korea’s healthcare system, it helped curtail the spread of the virus (Galiero et al., 2020; Kwon & Lee, 2020; Yonhap, 2020). It also avoided the need for patients to visit hospitals. Findings also suggested that telemedicine was useful for caring for patient undergoing palliative treatment or for management of chronic disorders during the pandemic by reducing hospital visitation (Perrone et al., 2020).However, this may not necessarily be convincing, as only 52% o the participants acknowledge that there is a need for a full implementation of telemedicine in a South Korean post-COVID-19 healthcare system. These show that even as telemedicine provides support to traditional medicine, there is still a considerable level hesitation among healthcare providers in South Korea regarding its potential (Galiero et al., 2020; Kwon & Lee, 2020; Yonhap, 2020). In any case, the demonstrated usefulness of telemedicine in helping to curtail coronavirus shows that during pandemics when application of traditional medicine is not realistic, telemedicine becomes a vital tool. This is consistent with findings in this research showing that telemedicine mitigates the spread of viral infections while simultaneously making it possible for patient to continue their diagnostic-therapeutic process. Of the participants surveyed, 78 acknowledged the usefulness of telemedicine in this regard.Findings further suggest that telemedicine leads to hospital avoidance. Of the participants surveyed, 80.8% stated that telemedicine did indeed lead to hospital avoidance during the COVID-19 pandemic. In effect, while it is clear that medical examination still remains the keystone of patient care, telemedicine reduces the number of patient attendances since consultations occur over the telephone or through e-mails. Hence, telemedicine can facilitate hospital avoidance, which can in turn cut costs, particularly by reducing emergency department presentations (Comín-Colet et al., 2016). Galiero et al. (2020) also found evidence showing that telemedicine can provide practical measures for taking care of individuals either in nosocomial isolation. For this type of scenario, telehealth services provide sufficient safety to both caregivers and clinicians, as it limits a direct contact with the infected persons (Lurie and Carr, 2018).Cost saving comes about as the need for transportation to the hospitals is eliminated, unless found to be necessary. Hospital avoidance becomes particularly important during pandemics when the value of travel restrictions and social distancing measures is emphasised. This serves to indicate that in a post-COVID-19 healthcare system, telemedicine may still be necessary to cut overcrowding in hospitals, streamline outpatient visits, and reduce the cost of care through hospital avoidance.Nevertheless, these also come at a cost. Of the participants surveyed, only 33% stated that telemedicine can effectively help in diagnosis or disease assessment. Essentially, this indicates when diagnosis is yet to be made, telemedicine may vital in diagnostic processes where external signs are needed to identify a disease. On the other hand, telemedicine may not be satisfactory where laboratory tests are required (Perrone et al., 2020). This shows that telemedicine has its limitations and could strictly be used as a support tool for in-person consultation, as it does not permit the same level of physical contact that physicians would need to identify details that require a thorough physical medical examination.Findings also suggest that telemedicine facilitates effective for monitoring chronic diseases. As stated, 61.5% of the participants agreed to have found telemedicine to be useful for this purpose. Ideally, this entails carrying out an ongoing in-home recording of a patient’s target biometric readings. Hence, telemedicine is determined to be useful in the treatment and management of chronic disorders during pandemics. It is useful for patients undergoing palliative treatment and improving clinician’s productivity. Previous research has demonstrated that when telemedicine eliminates or reduces medical practitioners’ travel time since service delivery happens via videoconference, their productivity improves as they can attend to more patients within the same time frame (Snoswell et al, 2020). In any case, current research data also indicated that participants did face challenges with diagnosis whenever they used teleconsulting to engage with patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the participants, 33% agreed to have faced challenges with diagnosis using teleconsulting. This may explain why 52% of the participants admitted to be unwilling to fully transition to telemedicine.

6. Conclusions

- Regulations that restrict telemedicine would make it difficult for patients to confer with physicians, in spite of an upward acceptance of remote consultations to improve the ease of use of health care for underserved communities. South Korea’s current legislations that ban or restrict telemedicine practice in South Korea could have made it difficult to curtail the spread of COVID-19 in the country. The government’s decision to temporarily lift them was opportune. Findings in this study suggest a need to lift the legislative restrictions on telemedicine for the country’s post-COVID-19 healthcare systems. Healthcare providers’ growing support for telemedicineseems to be attributable to their direct experience with the benefits of telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic after the government temporarily eased telemedicine regulations and in the process opened up the digital health sector for growth.The benefits of telemedicine in South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic can be categorised into three: cost, access, and outcomes. While telemedicine does not seem to have replaced medical examination during Covid-19 pandemic in the context of South Korea’s healthcare system, it helped curtail the spread of the virus. It also avoided the need for patients to visit hospitals. It also improve care for patient undergoing palliative treatment or for management of chronic disorders during the pandemic by reducing hospital visitation. Healthcare service providers that substitute in-person consultations with brief video consultation can realise an improved capacity to attend to more patients in the same time frame. Healthcare service providers that substitute in-person consultations with asynchronous or virtual consultations experience improved productivity. This may tend to increase when more patients can be managed concurrently. Telemedicine also facilitate hospital avoidance, which has a potential to cut costs, particularly in reducing emergency department presentations. It also reduces a considerable number of needless outpatient appointments with medical specialists. In this case, cost saving would come about when the need for transportation to the hospitals is eliminated, unless found to be necessary.Practical Implications Telehealth services may not necessarily lead to short-term or medium-term cost savings. Because of this, health services that consider setting up telemedicine should be motivated to do so by focusing on other benefits of telehealth services, such as telemonitoring, instead of just cost savings’ potential.Asynchronous consultations have a greater potential to lessen consultation time with a physician, than in-person consultations. Healthcare service providers would attain improved productivity of their clinicians by setting up telehealth services.The results of this survey will help policymakers in South Korea to evaluate certain aspects of telemedicine that make it a vital tool for caring for patient undergoing palliative treatment or for management of chronic disorders during the pandemic by reducing hospital visitation, and its limitation. This could provide a basis for a more reasoned approach to lifting the restrictions on telemedicine in a post-COVID-19 healthcare system in South Korea.Implications for ResearchA number of opportunities for future research are identified. More studies should be undertaken to analyse the economic benefits of telehealth to conclusively demonstrate whether cost savings provides sufficient motivation for setting up telehealth services. For instance, while the usage of telehealth to undertake triage referrals in wound care, dermatology, ophthalmology, and otolaryngology have been shown to effectively cut needless outpatient appointments with patients, there appears to be a dearth of research in this area.Telemedicine is beneficial both the clinicians and patients. Still, an economic analysis of telemonitoring does not convincingly indicate cost savings. While there are studies that have reported considerable cost savings, there are some that reported very minimal savings. Research on its financial benefit for both the clinicians and patients is not necessarily conclusive. Future longitudinal researches should consider closing this research gap.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML