-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Bioinformatics Research

p-ISSN: 2167-6992 e-ISSN: 2167-6976

2012; 2(5): 68-78

doi: 10.5923/j.bioinformatics.20120205.01

Autotuned Multilevel Clustering of Gene Expression Data

Hasin Afzal Ahmed 1, Priyakshi Mahanta 1, Dhruba Kumar Bhattacharyya 1, Jugal Kumar Kalita 2

1Department of Comp. Sc. and Engg. ,TezpurUniversity, Napaam, 784028, India

2Department of Comp. Sc., University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, USA

Correspondence to: Dhruba Kumar Bhattacharyya , Department of Comp. Sc. and Engg. ,TezpurUniversity, Napaam, 784028, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

DNA microarray technology has revolutionized biological and medical research by enabling biologists to measure expression levels of thousands of genes in a single experiment. Different computational techniques have been proposed to extract important biological information from the massive amount of gene expression data generated by DNA microarray technology. This paper presents a top down hierarchical clustering algorithm that produces a tree of genes called GERC tree (GERC stands for Gene Expression Recursive Clustering) along with the generated clusters. GERC tree is an ample resource of biological information about the genes in an expression dataset. Unlike dendrogram, a GERC tree is not a binary tree. Genes in a leaf node of GERC tree represent a cluster. The clustering method was used with real-life datasets and the proposed method has been found satisfactory in terms of homogeneity, p value and z-score.

Keywords: Hierarchical Clustering, Divisive Clustering, Mean Squared Residue, Gene Expression Data

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- DNA microarray technology enables the biologists to monitor expression levels of thousands of genes in a single microarray experiment. There is a high demand of computational techniques to operate on the massive amount of expression data generated by DNA microarray technology to extract important biological information. Due to the large number of genes and complex gene regulation networks, clustering is a useful exploratory technique for analyzing such data. It groups data of interest into a number of relatively homogeneous groups or clusters where the intra-group object similarity is minimized and the inter-group object dissimilarity is maximized. Problems of automatically classifying data arise in many areas, and hierarchical clustering can be a very good approach in certain areas such as gene expression data analysis because it can present a hierarchical organization of the clusters.Extracting important biological knowledge from biological data is a difficult task. One very useful approach for providing insight into the gene expression data is to organize the genes in a hierarchy of classes, where genes in a class are more similar compared to its ancestor classes in the hierarchy. In this paper, we present a polythetic divisive hierarchical clustering algorithm that operates in two distinct steps. The first step generates a number of initial clusters and in the second step, these initial clusters are further processed to form a set of finer clusters. The algorithm advances clustering of microarray data in following ways (a) Extraction of initial clusters is faster and it does not require any proximity measure. (b) During discovery of final clusters, a proximity measure referred here as MRD(Mean Residue Distance) is used to find mutual distance among genes within a particular initial cluster instead of operating on the entire set. (c) The algorithm is capable of tuning the threshold to be used to decompose a node to its child nodes itself. (d) The algorithm stores the tree structure which can be later used in different applications. (e) The algorithm allows overlapping of genes among child nodes of a particular node.The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In section 2, we discuss related work. Section 3 presents the algorithm. Experimental results are reported in section 4. Finally, discussion and future work are reported in section 5 and section 6 respectively.

2. Related Work

- Hierarchical clustering usually generates a hierarchy of nested clusters or, in other words, a tree of clusters, also known as a dendrogram. Hierarchical clustering methods are categorized into agglomerative (bottom-up) and divisive (top-down). A large number of clustering techniques have been reported for analyzing gene expression data, such as Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA)[1], Self Organizing Tree Algorithm (SOTA)[2], Divisive Correlation Clustering Algorithm (DCCA)[3], Density-Based Hierarchical clustering method (DHC)[4] and Dynamically Growing Self-Organizing Tree (DGSOT)[5]. Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean adopts an agglomerative method to graphically represent the clustered dataset. The method is much favored by many biologists and has become one of the most widely-used tools in gene expression data analysis. However, it suffers from lack of robustness, i.e., a small perturbation of the dataset may greatly change the structure of the hierarchical dendrogram. DHC is a popular density based clustering algorithm. DHC is developed based on ‘density’ and ‘attraction’ of data objects. In the first level, an attraction tree is constructed to represent the relationship between the data objects in the dense area which is later summarized to a density tree. Another approach splits the genes through a divisive approach, called the Deterministic-Annealing Algorithm (DAA)[6]. Hierarchical clustering not only groups together genes with similar expression patterns but also provides a natural way to graphically represent the dataset allowing a thorough inspection. However, like UPGMA, a small change in the dataset may greatly affect the hierarchical dendrogram structure. Another drawback is its high computational complexity and vagueness of termination criteria.

3. The GERC Algorithm

- GERC is a polythetic divisive hierarchical clustering algorithm that operates in two distinct steps. This is an extended version of the article[7] where the method was introduced. In the first step of the algorithm, an initial cluster is formed and this initial cluster is further processed in the second step to form finer clusters. The algorithm accepts four input parameters i.e., reference gene, step down ratio, preferred node volume and MRD threshold. However, the last three parameters can be statistically computed from the expression data. The technique can operate on any high dimensional numeric domain.

3.1. Data Pre-processing

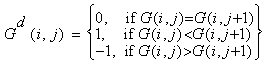

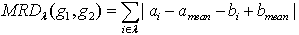

- Often gene data available on the web are found to contain missing values. The quality of clusters largely depends on the handling of these missing values. Apart from missing value handling, pre-processing also involves normalization and discretization.Handling missing valuesWe used the Local Least Squares Imputation method[8] to compute missing values in the datasets. There are two steps in the local least squares imputation method. The first step is to select k genes by Pearson correlation coefficient. The second step is regression using the selected k genes to estimate the missing values.NormalizationThe datasets are normalized using a common statistical method that converts each gene to a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1. This statistical method of normalization is often termed as Z score normalization[9] or Mean 0 Standard Deviation 1 normalization.DiscretizationThe normalized matrix is discretized to a matrix by comparing a value in a column with the value in the next column of the same row. The normalized matrix consists of three discrete values 1 (if the next value is larger) , -1 (if the next value is smaller) and 0 (if the next value is equal). The normalized matrix G can be converted to the discretized matrix Gd in the following manner.

3.2. Proximity Measure

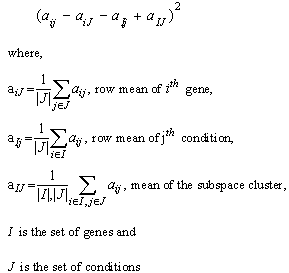

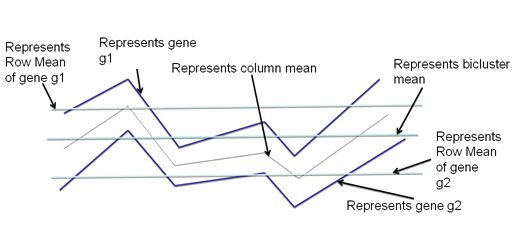

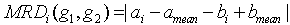

- In this paper, we introduce a simplified form of mean squared residue measure, i.e., Mean Residue Distance(MRD) to find mutual distance of two genes that aids in extracting the coherent patterns in the expression matrix. Like mean squared residue measure, MRD is a measure that works satisfactorily to detect coherence of constant valued genes, constant row genes, constant column genes and additive genes. The significance of these correlations in clustering of gene expression data is reported in[10]. Unlike MSR, MRD can operate in mutual mode i.e., it can compute correlation between a pair of genes. Next we discuss the mean squared residue measure and then introduce MRD measure.Mean Squared ResidueMean squared residue is a measure that was used to find coherent objects in a data matrix by[11]. They tried to find out a subset of genes along with a subset of conditions which has mean squared residue less than a threshold δ. They termed such subspace clusters as δ biclusters.The measure is still considered a strong one to detect coherent objects if it is used carefully. Various subspace clustering algorithms use mean squared residue directly or with a bit of modification. Mean squared residue of an element aij in gene expression matrix is given by,

Mean squared residue of a subspace cluster is computed as,

Mean squared residue of a subspace cluster is computed as,

| Figure 1. Visual interpretation of Mean Squared Residueo |

Where amean is the mean of all the elements of g1 and bmean is the mean of all the elements of g2. MRD of the gene pair g1 and g2 with respect to a subspace of conditions λ can be computes as,

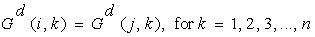

Where amean is the mean of all the elements of g1 and bmean is the mean of all the elements of g2. MRD of the gene pair g1 and g2 with respect to a subspace of conditions λ can be computes as, Following definitions and theorems provide the theoretical basis and soundness of the proposed measure based on [12].Definition 1: Coherent genes: Two genes are called coherent if similarity between the two genes is more than a given threshold in terms of a particular proximity measure.Definition 2: Expression pattern: The expression pattern of a gene is defined as the discretized form of the gene expression values. Two genes are said to have similar expression pattern if their discretized values are same. Mathematically, two genes gi and gj have similar expression pattern if

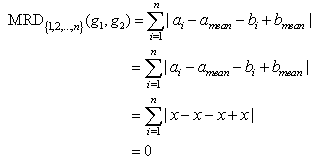

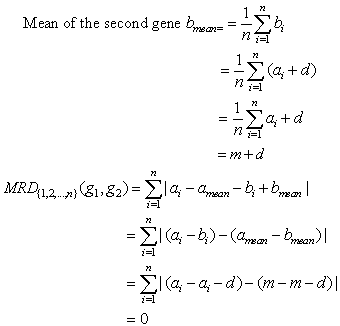

Following definitions and theorems provide the theoretical basis and soundness of the proposed measure based on [12].Definition 1: Coherent genes: Two genes are called coherent if similarity between the two genes is more than a given threshold in terms of a particular proximity measure.Definition 2: Expression pattern: The expression pattern of a gene is defined as the discretized form of the gene expression values. Two genes are said to have similar expression pattern if their discretized values are same. Mathematically, two genes gi and gj have similar expression pattern if Where n is the total number of conditions.Definition 3: Constant valued genes: For two genes gi=(a1, a2,...., an) and gj=(b1, b2,..., bn) if a1=a2=...=an=b1=b2=...=bn, then the genes are called constant valued genes.Definition 4: Constant row genes: For two genes gi=(a1, a2,...., an) and gj=(b1, b2,..., bn), if a1=a2=...=an and b1=b2=...=bn, then the genes are called constant row genes.Definition 5: Constant column genes: For two genes gi=(a1, a2,..., an) and gj=(b1, b2,..., bn), if a1=b1, a2=b2, ..., an=bn, then the genes are called constant column genes.Definition 6: Additive genes: For two genes gi=(a1, a2,...,an) and gj=(b1, b2,...,bn) if b1=a1+d, b2=a2+d, ..., bn=an+d, where d is an additive constant, then the genes are called additive genes.Properties of MRDThe MRD measure is capable of detecting four types of coherence (a) Coherence among constant valued genes (b) Coherence among constant row genes (c) Coherence among constant column genes (d) Coherence among additive genes. Next we present some of the properties of MRD.Theorem 1. MRD of two constant valued genes is always zero.Proof:Let the two genes be g1=(a1, a2,..., an) and g2=(b1,b2,..., bn). Since the two genes are constant valued soa1=a2=...=an=b1=b2=...=bn=x (say).Now mean of the two genes will be, amean=bmean=x.

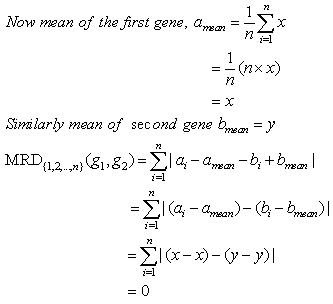

Where n is the total number of conditions.Definition 3: Constant valued genes: For two genes gi=(a1, a2,...., an) and gj=(b1, b2,..., bn) if a1=a2=...=an=b1=b2=...=bn, then the genes are called constant valued genes.Definition 4: Constant row genes: For two genes gi=(a1, a2,...., an) and gj=(b1, b2,..., bn), if a1=a2=...=an and b1=b2=...=bn, then the genes are called constant row genes.Definition 5: Constant column genes: For two genes gi=(a1, a2,..., an) and gj=(b1, b2,..., bn), if a1=b1, a2=b2, ..., an=bn, then the genes are called constant column genes.Definition 6: Additive genes: For two genes gi=(a1, a2,...,an) and gj=(b1, b2,...,bn) if b1=a1+d, b2=a2+d, ..., bn=an+d, where d is an additive constant, then the genes are called additive genes.Properties of MRDThe MRD measure is capable of detecting four types of coherence (a) Coherence among constant valued genes (b) Coherence among constant row genes (c) Coherence among constant column genes (d) Coherence among additive genes. Next we present some of the properties of MRD.Theorem 1. MRD of two constant valued genes is always zero.Proof:Let the two genes be g1=(a1, a2,..., an) and g2=(b1,b2,..., bn). Since the two genes are constant valued soa1=a2=...=an=b1=b2=...=bn=x (say).Now mean of the two genes will be, amean=bmean=x. Theorem 2. MRD of two constant row genes is always zero.Proof:Let the two genes be g1=(a1, a2,..., an) and g2=(b1,b2,..., bn). Since these are constant row genes, so a1=a2=a3=...=an=x (say) and b1=b2=b3=...=bn=y (say).

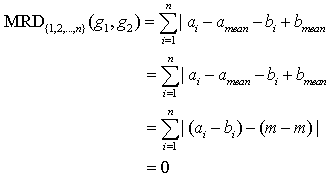

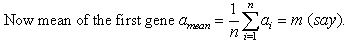

Theorem 2. MRD of two constant row genes is always zero.Proof:Let the two genes be g1=(a1, a2,..., an) and g2=(b1,b2,..., bn). Since these are constant row genes, so a1=a2=a3=...=an=x (say) and b1=b2=b3=...=bn=y (say). Theorem 3. MRD of two constant column genes is always zero.Proof:Let the two genes be g1=(a1, a2,..., an) and g2=(b1,b2,..., bn). Since these are constant column genes, so a1=b1, a2=b2,..., an=bn.Now mean of two genes will be amean=bmean=m(say).

Theorem 3. MRD of two constant column genes is always zero.Proof:Let the two genes be g1=(a1, a2,..., an) and g2=(b1,b2,..., bn). Since these are constant column genes, so a1=b1, a2=b2,..., an=bn.Now mean of two genes will be amean=bmean=m(say). Theorem 4. MRD of two additive genes is always zero.Proof:Let the two genes be g1=(a1, a2,..., an) and g2=(b1,b2,..., bn). Since the genes are additive, so bi=ai+d, for i=1,2,3,...,n. Here d is an additive constant.

Theorem 4. MRD of two additive genes is always zero.Proof:Let the two genes be g1=(a1, a2,..., an) and g2=(b1,b2,..., bn). Since the genes are additive, so bi=ai+d, for i=1,2,3,...,n. Here d is an additive constant.

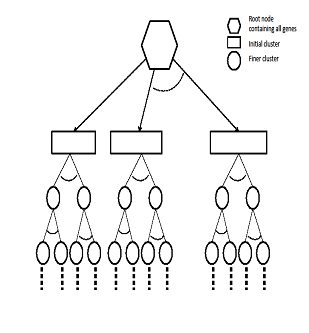

| Figure 2. Structure of GERC tree |

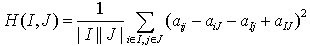

3.3. GERC Tree

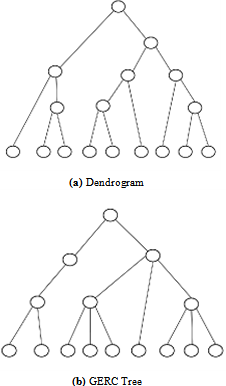

- Our algorithm results a tree called GERC tree. The leaves of this tree present the generated clusters of the algorithm. This tree can be used to derive additional biological information from a gene expression dataset. The overall structure of the tree generated for more than one reference gene is presented in Fig. 2.Dendrogram versus GERC treeA dendrogram is binary tree that presents the hierarchical structure of the clusters generated by a hierarchical algorithm. In divisive hierarchical algorithm, dendrogram is obtained by recursively splitting a node containing a set of objects into two child nodes based on the similarity among the object pairs until all nodes have a single object. Conversely, in agglomerative approach, the nodes containing a single object are recursively merged until all the objects are in the root node. But in our algorithm, GERC tree is obtained by recursively splitting a single node containing the set of all objects into multiple nodes(with possibly common objects) until number of objects in all the processing nodes is less than or equal to a user given threshold, i.e. preferred node volume. Unlike Dendrogram, GERC tree is not a binary tree and the structure of the tree is flexible depending on the values of the set of input parameter. The structural difference between dendrogram and GERC tree is presented in Fig. 3.

| Figure 3. Dendrogram versus GERC tree |

|

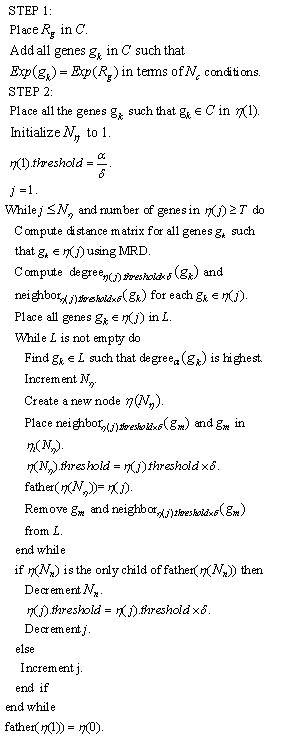

3.4. Proposed Algorithm: GERC

- Following definitions, symbols and notations are used to describe the GERC algorithm.

|

In GERC, the reference gene is used as an input parameter. The algorithm tries to find the initial cluster to which this gene potentially belongs to. While finding this initial cluster it tries to locate all genes which have similar expression pattern with the reference gene in terms of at least (Nc/2)+1 number of conditions. If we want to explore the entire dataset we can use each of the available genes or a set of stochastically selected genes as reference genes. Once we discover the initial clusters we move to step 2 of the algorithm. In the second step, we create a single node first with all genes of the initial cluster in it and then iteratively cluster each node(having genes more than preferred volume umber of genes) of the tree until all the processing nodes in the tree have less than or equal to preferred volume number of genes. The input parameter step down ratio is actually used to reduce the value of MRD threshold as towards leaf nodes of the tree the similarity among genes increases and require a smaller value of MRD threshold. e.g. if the MRD threshold provided by user is 1 and step down ratio is .5, then the first node will use 1 as its MRD threshold while clustering. On successful division of the node to its children, the successive level nodes will use thresholds .5(1*.5),.25(.5*.5) …. and so on. Finally the sub-trees (one sub-tree in case of single reference gene) generated from the initial clusters are combined to form the GERC tree. The roots of these subtrees are made children of a single node that contains the set of entire genes and this node becomes the root of generated GERC tree.

In GERC, the reference gene is used as an input parameter. The algorithm tries to find the initial cluster to which this gene potentially belongs to. While finding this initial cluster it tries to locate all genes which have similar expression pattern with the reference gene in terms of at least (Nc/2)+1 number of conditions. If we want to explore the entire dataset we can use each of the available genes or a set of stochastically selected genes as reference genes. Once we discover the initial clusters we move to step 2 of the algorithm. In the second step, we create a single node first with all genes of the initial cluster in it and then iteratively cluster each node(having genes more than preferred volume umber of genes) of the tree until all the processing nodes in the tree have less than or equal to preferred volume number of genes. The input parameter step down ratio is actually used to reduce the value of MRD threshold as towards leaf nodes of the tree the similarity among genes increases and require a smaller value of MRD threshold. e.g. if the MRD threshold provided by user is 1 and step down ratio is .5, then the first node will use 1 as its MRD threshold while clustering. On successful division of the node to its children, the successive level nodes will use thresholds .5(1*.5),.25(.5*.5) …. and so on. Finally the sub-trees (one sub-tree in case of single reference gene) generated from the initial clusters are combined to form the GERC tree. The roots of these subtrees are made children of a single node that contains the set of entire genes and this node becomes the root of generated GERC tree.3.5. Complexity Analysis

- Since GERC involves two distinct steps, hence the total complexity is the sum of the complexities of these two steps. Let a dataset contains n number of genes. In the first step of the algorithm, the total number of comparisons done to put all n number of genes in the initial cluster is n-1. In the second step, if the number of genes in the initial cluster is p, the computation of distance matrix involves px(p-1)/2 operations. If the average number of genes in the non leaf nodes is m and the total number of non leaf nodes is l, creating the child nodes and hence the entire tree requires l*m operations. So complexity of the second step is O (px(p-1)/2+ l*m).

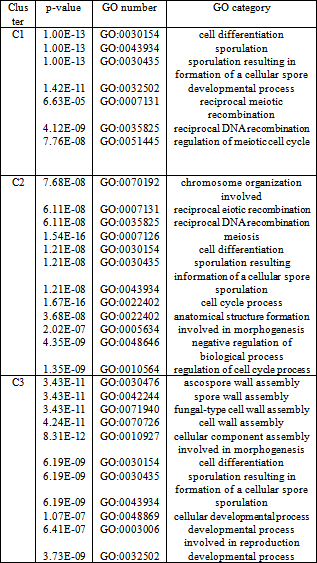

4. Experimental Results

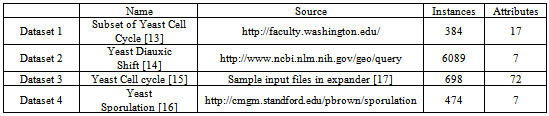

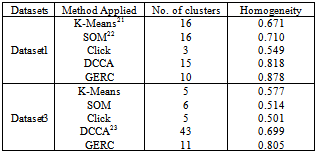

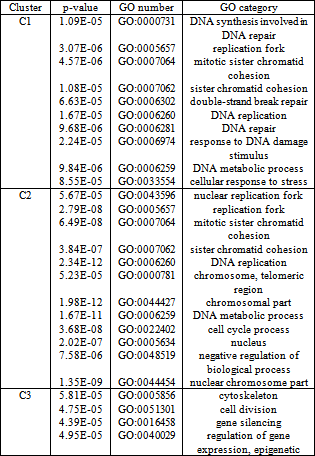

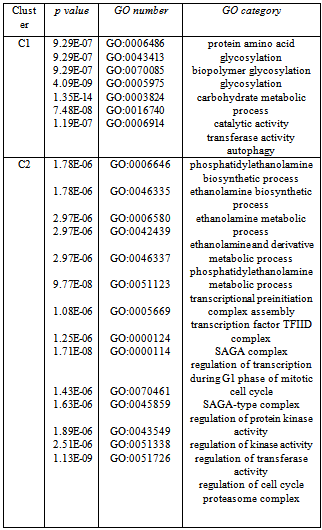

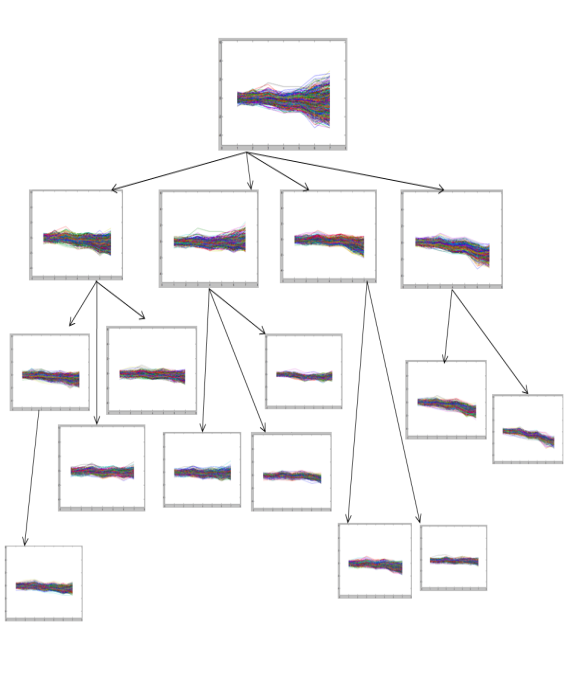

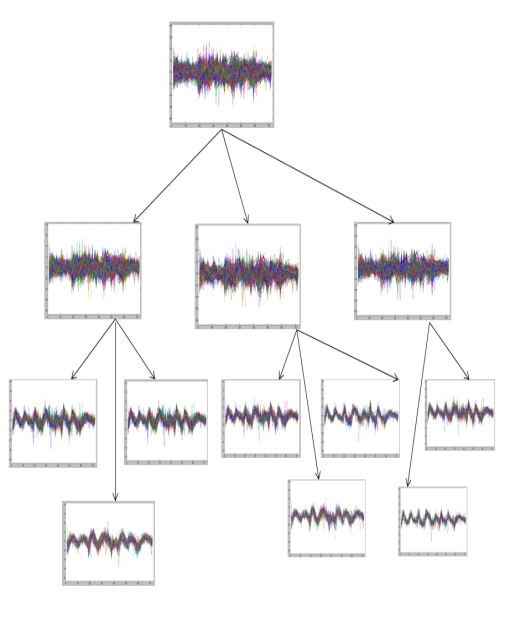

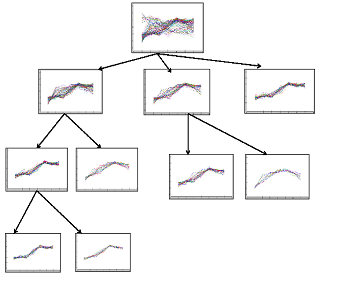

- We implemented the GERC algorithm in MATLAB and tested it on four publicly available benchmark microarray datasets mentioned in Table 4. The test platform was a desktop PC with Intel Core 2 Duo 2.00 GHz processor and 512 MB memory running Windows XP operating system. Fig. 5, 6 and 7 present a part of the tree generated from an initial cluster for Dataset 2, Dataset 3 and Dataset 4 respectively.

4.1. Cluster Quality

- The GERC algorithm was compared with various clustering algorithms and the results were validated using average homogeneity score[18], p value[19] and z score[20].Cluster Homogeneity: Homogeneity measures the quality of clusters on the basis of the definition of a cluster i.e., Objects within a cluster are similar while objects in different clusters are dissimilar. It is calculated as follows.(a) Compute average value of similarity between each gene gi and the centroid of the cluster to which it has been assigned.(b) Calculate average homogeneity for the clustering C weighted according to the size of the clusters.

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- We have presented here a clustering algorithm that generates a tree where the children of a node represent the clusters that are formed from the genes in that node. The leaf nodes of the tree will represent the desired clusters. We keep on reducing the threshold used in the clustering process as we move on to deeper levels. The structure of the generated tree is driven by the input parameters. The input parameters T and δ controls the height/depth of the tree. If we set the value of T large the genes in the root node will split to the leaf nodes in a few numbers of levels.

|

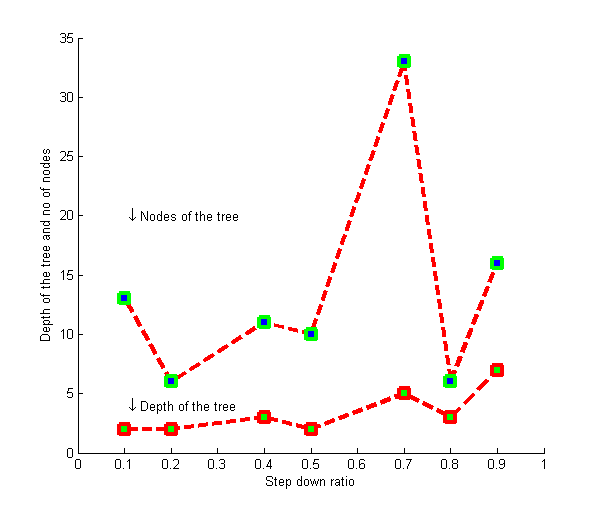

| Figure 4. Tuning the value of δ for Dataset 3 |

|

6. Conclusions and Future Work

- In this paper, we present a top down hierarchical clustering algorithm that produces a tree of genes in the neighbourhood of a reference gene called GERC tree along with the generated clusters. The algorithm can be used to generate a wide range of clusters by considering multiple reference genes. Clustering performed in the nodes at different levels of GERC tree adaptively chooses the values of threshold parameters. The complexity of our approach can be improved by using an appropriate heuristic method for estimating an effective set of parameter values which will guarantee for quality cluster results. The value of α and R can also be calculated statistically from the set of input genes. Work is underway for integrating prior biological information to the clustering process to improve the results.

|

| Figure 5. Tree generated from an initial cluster for yeast Dataset 2 |

| Figure 6. Tree generated from an initial cluster for yeast Dataset 3 |

| Figure 7. Tree generated from an initial cluster for yeast Dataset 4 |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This work is an outcome of the research project in collaboration with CSIR, ISI, Kolkata funded by DST, Govt. of India. The work is also supported by INSPIRE programme of DST, Govt. Of India.

References

| [1] | M. B. Eisen, P. T. Spellman, P. O. Brown, and D. Botstein, “Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns,” Proceedings of Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., vol. 95, pp. 14 863–14 868, 1998. |

| [2] | J. Dopazo and J. Carazo, “Phylogenetic reconstruction usingan unsupervised neural network that adopts the topology of aphylogenetic tree,” J Mol Eval, vol. 44, pp. 226–233, 2002. |

| [3] | A. Bhattacharya and R. K. De, “Divisive correlation clutering algorithm (dcca) for grouping of genes,” Bioinformatics, vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 1359–1366, June 2008. |

| [4] | D. Jiang, J. Pei, and A. Zhang, “Dhc:a density-based hierarchical clustering method for time series gene expression data,” Proceedings of IEEE International Symposium on Bioinformatic and Bioengineering, pp. 393-400, 2003. |

| [5] | F. Luo, L. Khan, F. Bastani, I. L. Yen and J. Zhou, “A dynamically growing self-organizing tree (dgsot) for hierarchical clustering gene expression profiles,” Bioinformatics, vol. 20, no. 16, pp. 2605–2617, 2004. |

| [6] | K. Rose, “Deterministic annealing for clustering, compression, classification, regression, and related optimization prob-lems,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 86, no. 11, pp. 2210–2239, 2002. |

| [7] | H. A. Ahmed, P. Mahanta, D. K. Bhattacharyya and J. Kalita, “GERC: Tree based clustering for gene expression data,” Proceedings of 2011 IEEE 11th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering, pp. 299-302, 2011. |

| [8] | H. Kim, G. H. Golub and H. Park, “Missing value estimation for DNA microarray gene expression data: local least squares imputation,” Bioinformatics, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 187–198, 2005. |

| [9] | R. Das, J. Kalita and D. K. Bhattacharyya, “A new approachfor clustering gene expression time series data,” Int. J. Bioinformatics Res. Appl., vol. 5, pp. 310–328, 2009. |

| [10] | S. C. Madeira and A. L. Oliveira, “Biclustering algorithm for biological data analysis: A survey,” IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinformatics, vol. 1, pp. 24–45, 2004. |

| [11] | Y. Cheng and G. M. Church, “Biclustering of expression data,” Proceedings of the eighth International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology, vol. 1, pp. 93–103, 2000. |

| [12] | A. Mukhopadhyay, U. Maulik, S. Bandyopadhyay, “A novel coherence measure for discovering scaling biclusters from gene expression data,” J. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 853-868, 2009. |

| [13] | R. J. Cho, M. J. Campbell, E. A. Winzeler, L. Steinmetz, A. Conway, L. Wodicka, T. G. Wolfsberg, A. E. Gabrielian, D. Landsman, D. J. Lockhart, and R. W. Davis, “A genome-wide transcriptional analysis of the mitotic cell cycle,” Molecular cell, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 65–73, 1998. |

| [14] | J. L. DeRisi, V. R. Iyer and P. O. Brown, “Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale,” Science, vol. 278, no. 5338, pp. 680-686, 1998. |

| [15] | P. T. Spellman, G. Sherlock, M. Q. Zhang, V. R. Iyer, K. Anders, M. B. Eisen, P. O. Brown, D. Botstein and B. Futcher, “Comprehensive identification of cell cycle–regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization,” Molecular biology of the cell, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 3273–3297, 1998. |

| [16] | S. Chu, J. DeRisi, M. Eisen, J. Mulholland, D. Botstein, P. O. Brown and I. Herskowitz, “The transcriptional program of sporulation in budding yeast,” Science, vol. 282, no. 5389, pp. 699–705, 1998. |

| [17] | I. Ulitsky, A. Maron-Katz, S. Shavit, D. Sagir, C. Linhart, R. Elkon, A. Tanay, R. Sharan, Y. Shiloh and R. Shamir, “Expander: from expression microarrays to networks and functions,” nature protocols, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 303–322, 2010. |

| [18] | R. Sharan and R. Shamir, “Click: A clustering algorithm with applications to gene expression analysis,” Proceedings of the eighth International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology, vol. 8, pp. 307–316, 2000. |

| [19] | G. F. Berriz, O. D. King, B. Bryant, C. Sander, and F. P. Roth,“Characterizing gene sets with FuncAssociate.” Bioinformatics, vol. 19, no. 18, pp. 2502–2504, 2003. |

| [20] | F. Gibbons, F. Roth, “Judging the quality of gene expression-based clustering methods using gene annotation,” Genome Research, vol. 12 , pp. 1574-1581, 2002. |

| [21] | J. A. Hartigan and M. A. Wong, “A k-means clustering algorithm,” JSTOR: Applied Statistics, vol. 28, pp. 100–108, 1979. |

| [22] | T. Kohonen, “The self-organizing map,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 78, no. 9, pp. 1464-1480, 1990. |

| [23] | S. Sarmah, R. D. Sarmah, D. K. Bhattacharyya, “An effective density-based hierarchical clustering technique to identify coherent patterns from gene expression data,” Proceedings of the 15th Pacific Asia conference on Advances in knowledge discovery and data mining,” pp. 225-236, 2011. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML