Stella Mouzakiotou

Art Historian, Hellenic Open University & University of West Attica

Correspondence to: Stella Mouzakiotou, Art Historian, Hellenic Open University & University of West Attica.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

In this study there is a presentation of the concept and aesthetics of kitsch in art. Initially, an attempt is made to define the concept, to present the origin of the term and to highlight the key features that lead to its creation. Subsequently, the theoretical aspects of the kitsch concept are explored, as well as the emphasis on differences of the kitsch as a choice of political irony and kitsch as a style. Through this research we will show that it is grown rather early in school education. It is then enhanced through a multitude of cultural vehicles, the strongest of which is television, constantly bombarded with symbolic reports through advertisements, programs and news broadcasts. We will also explore the power of stereotypes and symbolic forms in people's lives, shaping a person's consciousness by promoting or inhibiting its collective political action. It is considered necessary to associate the term step by step with the Grotesque concept and its presence in the visual arts. In addition, the essay highlights its exploitation in totalitarian regimes and arts, such as visual arts and cinema, while research climaxes with the presentation of the political version of kitsch in the modern political life of Greece through the art of cartoon. The essay is finished with conclusions resulting from the analysis of the topic.

Keywords:

Grotesque, Kitsch, Monumentality, Interaction, Political kitsch, Mass culture

Cite this paper: Stella Mouzakiotou, Monumentality and Kitsch through a Relationship of Coexistence, Interaction, Conflict, International Journal of Arts, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 16-25. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20201001.03.

1. Introduction

Kitsch, as a concept, varies according to the intention and aim of its creator. There is, on the one hand, the artist's intentional use of excessive, ugly, ironic and pompous elements in his work to cause intense emotions, to convey specific messages to the public, to cause comments and at the same time counter-reactions. On the other hand, there is the version of kitsch that is clearly only an innocent, painless and unforced expression and aesthetics of its creator.While Umberto Eco argues that "the excessive accumulation of kitsch elements is a remarkable stylistic proposition," Walter Benjamin approaches the term stating that, unlike art, the presence of kitsch is found when any critical approach is absent in a critical approach between it and the observer. This is the case where the viewer is offered a direct emotional "analgesic" where the viewer does not need to make any intellectual effort to understand. In addition, for Adorno, kitsch must maintain an inherent link with "mass culture" through a trend that has prevailed so that more and more people are getting closer to Art.Kitsch has also been described as an art that uses everyday experiences that appeal to citizens' beliefs and feelings, encouraging vanity, prejudices or unwarranted fears. While it may occasionally be annoying, in most cases, through its incredible immediacy, it provides us with the ability to build and exploit the cultural myths and values of societies and to manipulate them in such a way as to create a strong political fabrication that has been designed to reassure and comfort the observer - consumer. Its creators know the cultural prejudices of a particular audience and deliberately exploit them. So, through such a kaleidoscope of thoughts and aesthetic approaches, we will explore the concepts of "Monumentality" and "kitsch" through their coexistence, interaction and conflict in the modern urban landscape.

2. Chapter 1

A. Definition of kitschThe term Kitsch has usually a deceptive orientation and renders the description of artistic works whose aesthetics are meager and cheap, having as their overarching purpose the superficial pleasure of the audience. First of all, the term relates to the designation of visual works, but was then "utilized" in all forms of art.The term appeared around 1870, in places of conversations about art in Munich, but its origin remains uncertain. According to one version, it is etymologically derived from the English word sketch, which was used by English-born tourists as they were looking for works of mainly landscaping by indigenous creators. In another version, the term derives from the German verb kitschen attributing the phrase "I gather mud on the road", meaning in a deceptive way the visitors who gathered paintings without any aesthetic criterion. For the first time the term with its international significance was used in the 1930s.B. General approach of the political kitschPolitical kitsch is a form of propaganda that is designed to steer the public political thinking towards to a specific direction.This is, therefore, a form of manipulation that involves familiar and easily understood forms of art, with the aim of shaping, rebalancing and directing public thought. Kitsch differs from art in that through the use of a constantly changing folk culture it turns into a powerful political weapon designed to "conquer" the receiver's consciousness. It reaffirms with plausibility what the receiver supports and facilitates him, by exploiting cultural myths and easily understood symbolisms.Kitsch has also been described as an art that uses everyday experiences or that addresses the beliefs and feelings of citizens by encouraging vanity, prejudice or unwarranted fears. While kitsch can be occasionally annoying, in most cases, through its incredible immediacy, it provides us with the ability to build and exploit the cultural myths of societies and to manipulate them in such a way as to create a strong political construction is designed to reassure and comfort the observer - consumer. Its creators know the cultural prejudices of a particular audience and deliberately exploit them.

3. Chapter 2

A. Theoretical views that constitute the concept of kitschIn this chapter we focus on a theatrical dialogue on kitsch, which was created by Austrian novelists Hermann Broch (1886-1951) and Robert Musil (1880-1942) between 1930 and 1950. More specifically, the two fiction writers make a differentiation of value between real and pseudo-art (or kitsch). Thus, their disagreement on this issue is emblematic of the dilemmas that still exist today and need aesthetic evaluation. While Broch's views deal with the aesthetics of speech through a metaphysical approach, assuming an almost idealistic perception of art, Musil frames the distinction between "good" and "bad" art in an empirical, relativistic understanding of aesthetic experience [1]. According to Catherine Lugg, "Kitsch is an art that deals with emotions and deliberately ignores the intellect and as such is a form of cultural anesthesia. This characteristic gives us the ability to build and exploit cultural myths - and to handle a colliding story easily - that makes Kitsch a strong political fabrication" [2].In England, former Prime Minister John Major probably profiled the concept of kitsch when he said: "In fifty years from now, Britain will still be the country with big shadows in cricket areas, hot beer, unbeaten green suburb, amateur dogs and billiards" [3].According to the Czech author Milan Kundera, "There is the kitsch behavior. The kitsch stop. The Kitsch mensch: the need to look at the deforming mirror of the embellishment and to recognize your face excited by satisfaction ... The word kitsch denotes the attitude of the man who wants to at all costs be liked by most people. But to be liked, he has to confirm everything the crowd wants to hear, he must be at the service of the cliché ... ". In particular, he thinks that even if we want to distance ourselves from kitsch, that is an integral part of our everyday life. The discerning writer, therefore, sees the necessity of it. [4]While Umberto Eco argues that "the excessive accumulation of kitsch elements is a remarkable stylistic proposition," Walter Benjamin approaches the term stating that, unlike art, the presence of kitsch is found when any critical approach is absent in a critical approach between it and the observer. This is the case where the viewer is offered a direct emotional analgesic, where the viewer does not have to make any mental effort to understand. In addition, for Adorno, kitsch must maintain an inextricable link with "mass culture" through a trend that has prevailed so that more and more people are getting closer to Art. [5]Clement Greenberg believed that the innovation was created to defend the patterns that arose from the decay of aesthetics that was perpetuated by the mass production of consumer society and saw kitsch and art as opposites. One of his most controversial claims was that kitsch was equivalent to academic art: "Everyone who is kitsch is an academic, and vice versa, what is academic is kitsch." He supported this view based on the fact that academic art focused on rules and forms taught and tried to make art incomprehensible and easy to understand. Later, of course, he was removed from this view of the equation of the two, as he was strongly criticized. [6]B. Kitsch as an option for political irony and kitsch as a styleKitsch, as a concept, varies according to the intention and feasibility of its creator. There is, on the one hand, the case of the artist who deliberately and intentionally uses in his work the excessive, the ugly, the ironic and the pompous elements to cause intense emotions, to convey to the public some messages, to cause comments and counter reactions at the same time. And on the other hand, there is the version of kitsch that is clearly only an innocent, painless and unforced expression and aesthetics of its creator.Charles Baudelaire in 1863, says that the lability of art was caused by the emergence of the engraving technique that inevitably led to mass production (postcards, posters, and so on). This resulted in the loss of the "glamor" of the work of art. [7]

4. Chapter 3

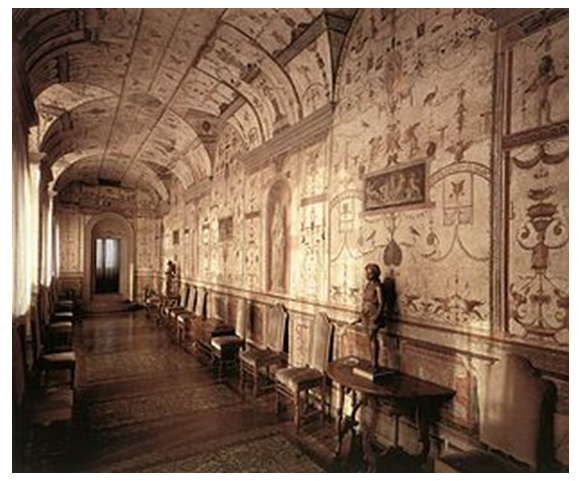

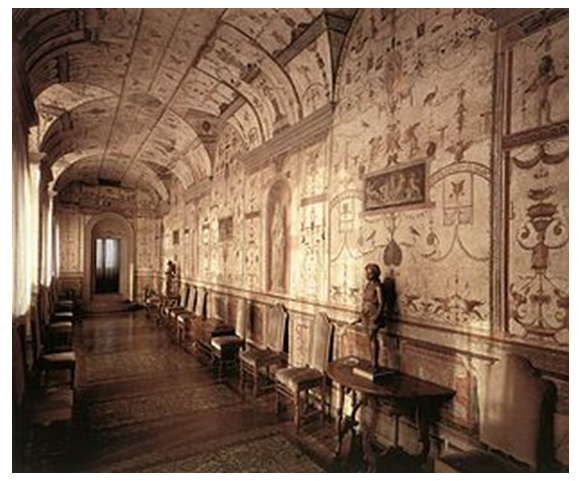

A. The development of the Grotesque concept in the visual artsThe decoration style that came directly from the findings of Domus Aurea [8] is called Grotesque. One of the first works to use Grottesche's style was the decoration of the private apartment and loggetta (fig.1) of the Bibbiena [9] cardinal, as well as the well-known loggia on the lower floor. The cardinal was characterized by his playful and extraordinary spirit and this may have influenced the releasing nature of the designs which, like other Raphael designs, became the original model for grotesque compositions and were more influential than the Roman prototypes of Domus Aurea. There was a rapid spread of Raphael's designs to other countries by artists who worked on loggia, as they were copied by countless other artists who traveled to the Vatican to study the works, while others had been given the copy of the entire composition. Grotesque, as a new style of painting, was developed very quickly across Europe in a great extent due to the appearance and spread of engravings in the graphic arts. [10] | Figure 1. Cardinal Bibbiena's logget, (1519). Source: it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loggetta_del_cardinal_Bibbiena |

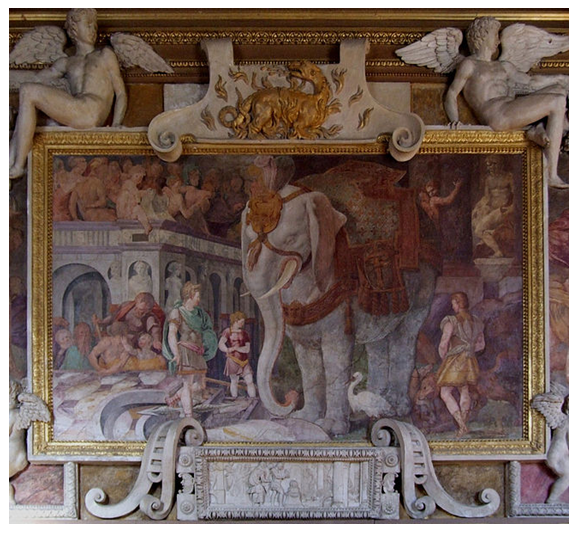

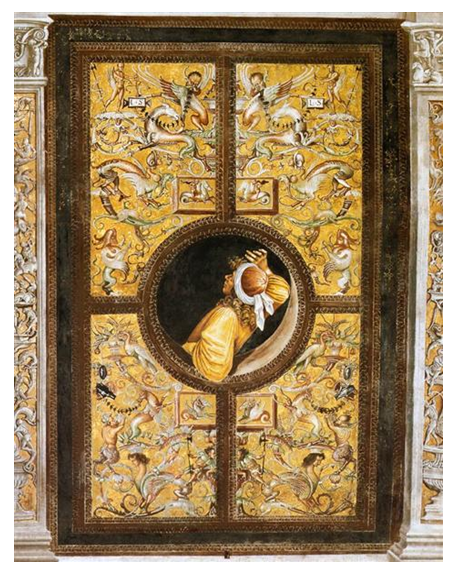

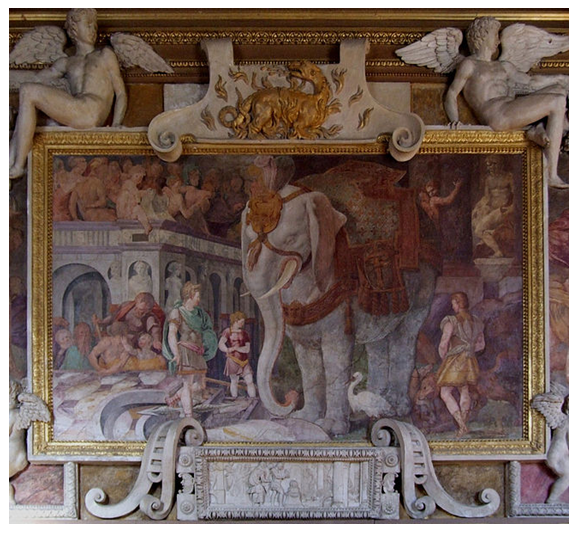

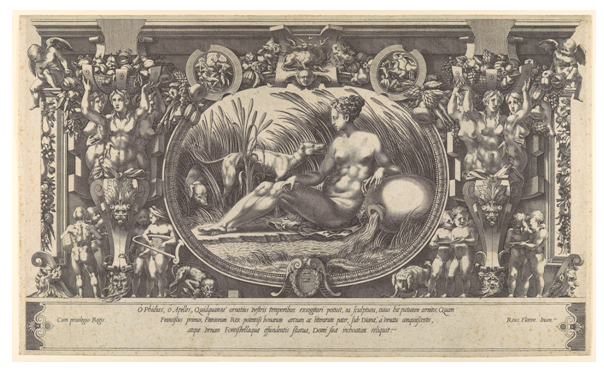

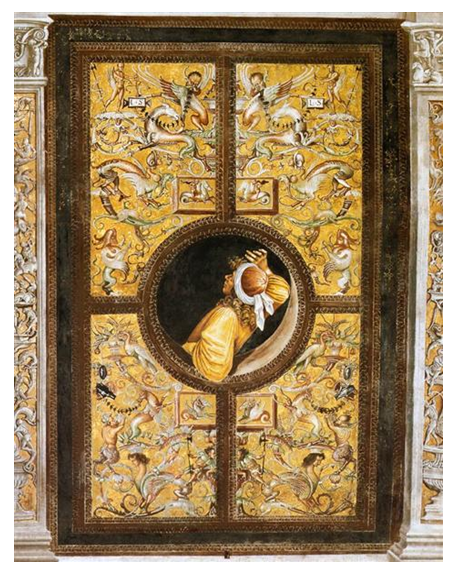

The 16th century graphic arts functioned as a modern internet as they promoted and facilitated the exchange of visual ideas at an unprecedented rate. In a wider field, the grotesque spread across the entire European culture in which it found patrons and sponsors with great influence, such as the Medici, Francis A of France and the Habsburgs. In 1530 and 1532 Francis called the Italian artists Il Rosso and Primaticcio to decorate his palace in Fontainebleau. These men, after 15 years of work, have created their own special interpretation of the grotesque, even more sophisticated and complicated (fig.2). The particular style of painting that Connelly1 calls scrollwork or strap work, along with the incredibly deformed figures that are knitted among the designs, has been very influential to artists and designers of the European North. After Francis' death, Fontainebleau artists scattered this particular style, gaining an even greater impact through its reproduction in etching prints, especially by engravers such as Rene Boyvin (fig.3). [11] | Figure 2. Rosso Fiorentino's painting at the Francis I gallery in the Fontainebleau palace, (1533-39). (Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fontainebleau_interior_francois_I_gallery_02.JPG) |

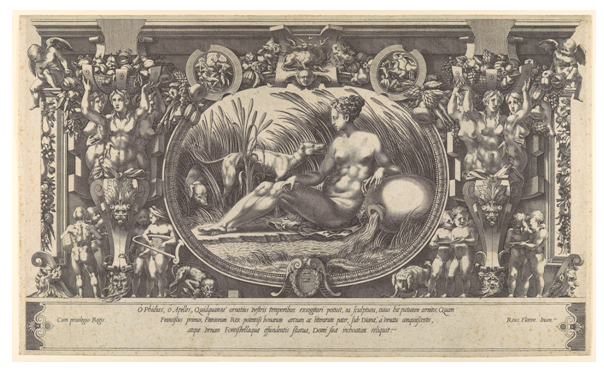

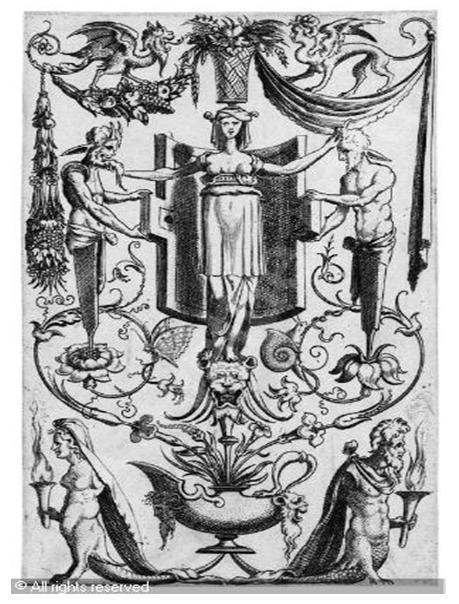

| Figure 3. The Fontaineblen nymph - René Boyvin, (1554). (Source: www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/32.105/) |

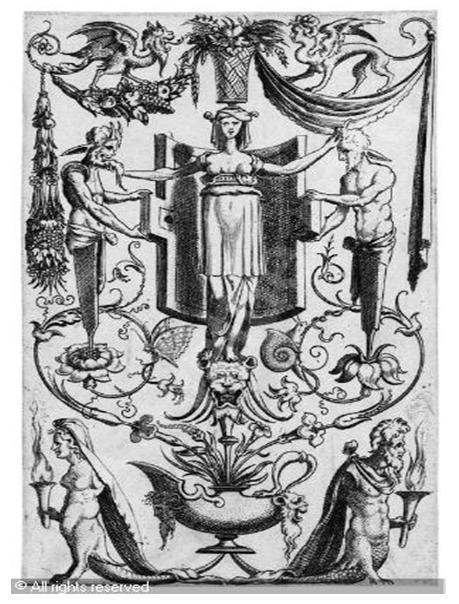

In an engraving of Cornelis Bos [12] of 1546, the classic grotesque is the organizational principle, but symmetry and class have been overturned by drollery (comic or drawing) performances. Nude satyrs and heroes are classical only by name and use the decorative frame as a playground by spreading their edges through each opening (Fig. 4). Bos seems to have created a classic structure to break it down. In the 16th century, artists saw the grotesque as more than just a decorative element. In the frescoes of Luca Signorelli (fig.5) in the Brizio chapel of the Orvieto Cathedral (1499), although the grotesque elements act as decorative elements, they are mixed with the main theme and change their primary meaning. [13]  | Figure 4. Engraving of Cornelis Bos, (1546). (Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Cornelis_Bos#/media/File: Cornelis_Bos_001.jpg) |

| Figure 5. Luca Signorelli, Detail of the Brizio chapel, (1499-1502). (Source: www.wikiart.org/en/luca-signorelli/empedocles-1502) |

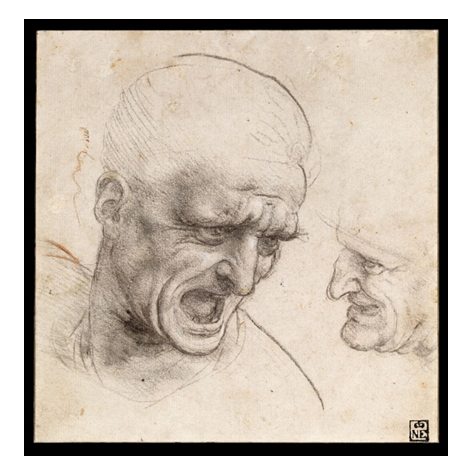

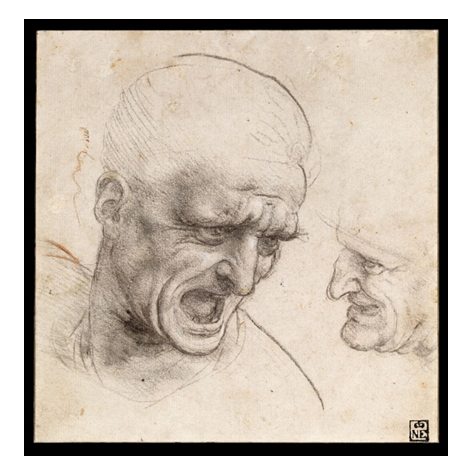

The illusion, the element of strange and visual fallacies are elements that seem to fascinate the artists of the late rebirth, and through these elements the connection of the grotesque with the art of the period is realized. Thus, we have the cases of Leonardo da Vinci (fig. 6), or Hans Holbein who in his work "The Ambassadors" (Fig. 7) uses perspective reformation to place a symbolic Vanitas, or Giuseppe Arcimboldo on Vertumnus .8). In Arcimboldo's work the highest personality, the emperor himself, is mixed with common fruit and vegetables. [14]  | Figure 6. Leonardo da Vinci, Study of Two Warriors' Heads for the Battle of Anghiari (c.1504-5). (Source: https: //commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Leonardo_da_Vinci _-_ Study_of_Two_Warriors% 27_Heads_for_the_Battle_of_Anghiari _-_ Google_Art_Project.jpg) |

| Figure 7. Hans Holbein - The Ambassadors, (1533). (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ambassadors_(Holbein)) |

| Figure 8. Giuseppe Arcimboldo - Vertumnus, (1590-1591). (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vertumnus_ (painting)) |

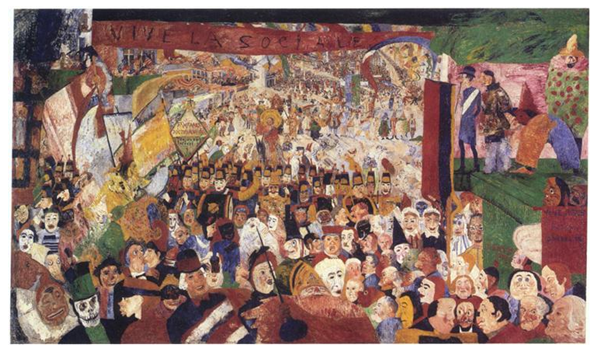

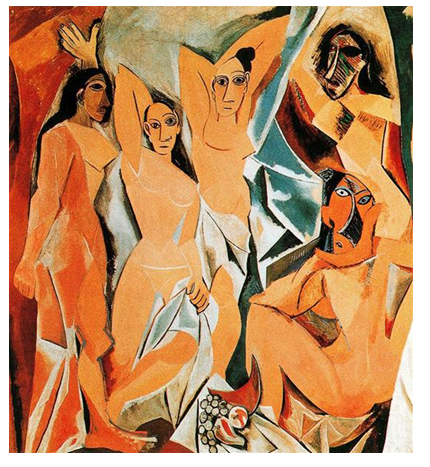

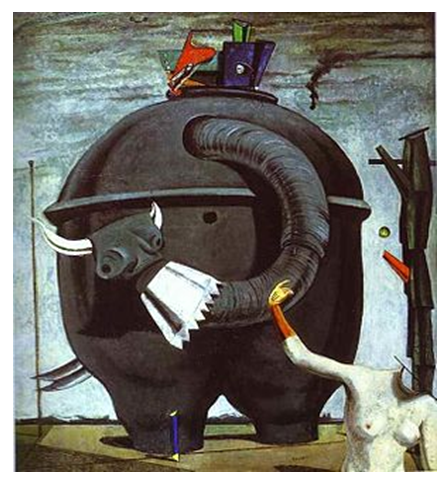

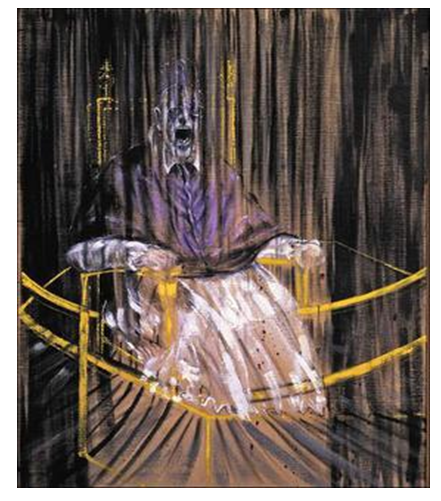

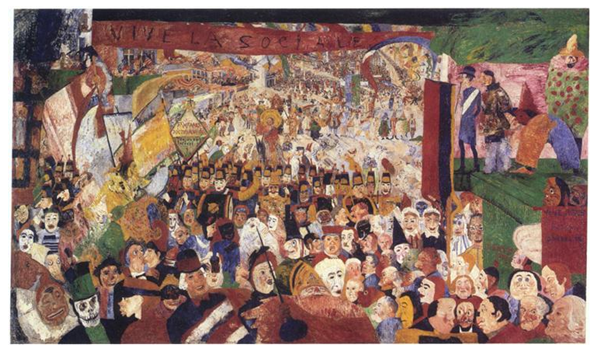

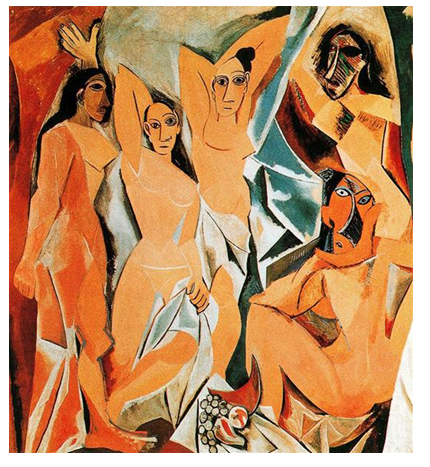

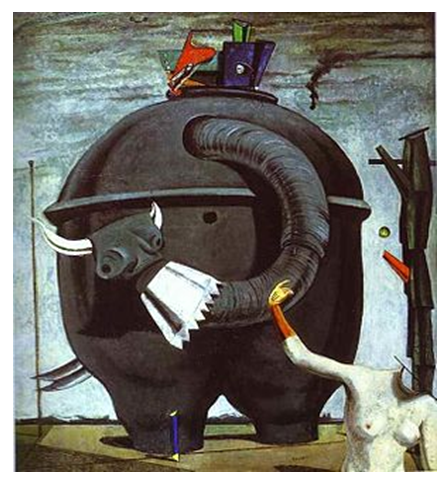

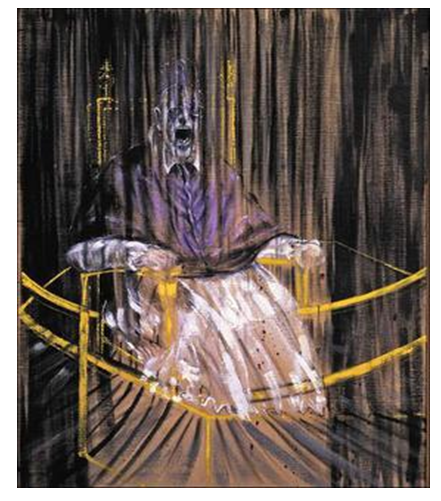

B. Grotesque in contemporary artSince the beginning of the 19th century grotesque has not been in the area of visual arts but has gained a place among the other elements that make up contemporary art. The romantic period marked the entrance of the grotesque into the prevailing trend of contemporary expression as a means of exploring new alternative modes of expression, but also as a means of provoking and challenging the established principles of classical beauty. The modern era became the scene of a real explosion of visual iconography in which the grotesque was incorporated in various ways. A large number of modernist works such as Théodore Géricault's “Le Radeau de la Méduse”, James Ensor's “L'Entrée du Christ à Bruxelles” (picture 9), “Les Demoiselles d'Avignon” by Pablo Picasso (fig.10), Max Ernst's “The Elephant Celebes” (Fig. 11) or Francis Bacon's “Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X “(Fig. 12), use structures that have deeply rooted in the Western artistic tradition and are known as grotesque. Grotesque appears prominently in the vocabulary of Romanticism, Symbolism, Expressionism, Primitivism, Realism and Surrealism, but also plays an important role in Cubism and some forms of abstraction. | Figure 9. James Ensor - L'Entrée du Christ à Bruxelles, (1888). (https://www.wikiart.org/en/james-ensor/christ-s-entry-into-brussels-in-1889-1888) |

| Figure 10. Pablo Picasso - Demoiselles d'Avignon, (1907). (Source: https://www.wikiart.org/en/pablo-picasso/the-girls-of-avignon-1907) |

| Figure 11. The Elephant Celebes - Max Ernst, (1921). (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Elephant_Celebes) |

According to Connelly [15], the re-emergence of grotesque in the fine arts was just one of the wide range of expressive ways in which grotesque was expanded and redefined in the 19th and 20th centuries. These cultural vehicles for the grotesque included a number of dissimilar fields such as psychoanalysis, photography, media, science fiction, ethnography, globalization and virtual reality. | Figure 12. Francis Bacon - Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, (1953). (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Study_after_Velázquez's_Portrait_of_Pope_Innocent_X) |

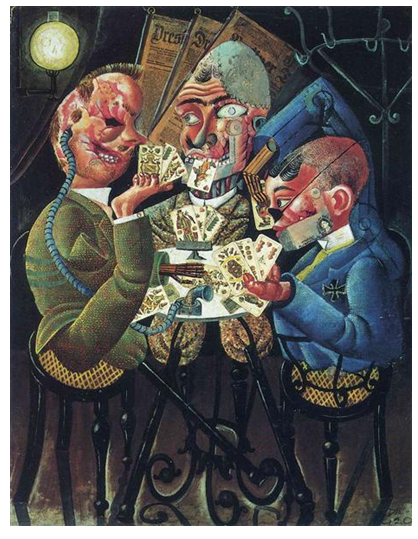

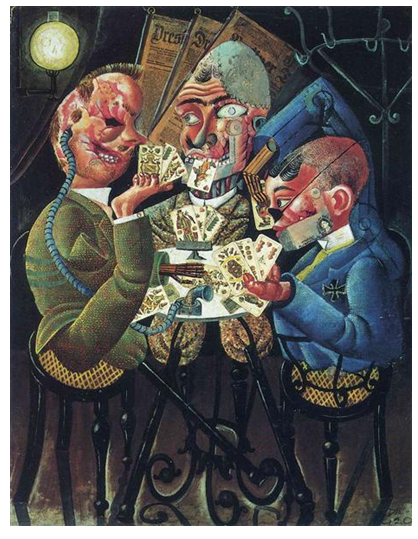

Connelly [16] gathers pictures-kitsch behind the title “grotesque” which can be grouped into three categories: those combining dissimilar things to challenge the established reality or to construct new ones, those in which what is depicted is deformed or disintegrated and those in which there is the element of transformation. These grotesque ones are not the same from one another and the breadth of their expression can start from the miraculous elements to the monstrous or to the ridiculous ones. The truncated figures of Otto Dix (fig. 13) are at the same time a kind of improvised constructions, made of the most incredible materials, but at the same time they act like caricatures and transmit a horror that is so alive that grips someone.  | Figure 13. Otto Dix - Die Skatspieler, (1920). (Source: www.wikiart.org/en/otto-dix/the-skat-players-1920) |

5. Chapter 4

A. Kitsch in totalitarian regimesAesthetics is in an interactive relationship with the society in which it is developed. Of course, this relationship is not so innocent, since in periods of totalitarian regimes aesthetics are determined and imposed by the respective authorities, so there is no free and healthy interaction in their contact with the citizens of these regimes. Within such a morbid, politically, environment, the aesthetic criterion of mass is formed and is entirely connected to the vehicle that the dictator imposes, totally directed and manipulated by his suggestions and desires. Thus, in Greece during the junta period, the adulation of classicism is strengthened, which we find in the architectural design of rich buildings where they are decorated with columns and tacky Aphrodites of Milos, while at the same time folk troubadours are heard from the turntable in their living room! The aim of the dictator is the revival of the glorious past and personalities as Alexander and Pericles, as he sought his presence on the political scene as a worthy follow-up. Also, we do not forget that the period of Hitler's Germany, Berlin was filled with buildings that mimiced the architecture of the Parthenon while in communist China, the group parades made reference to military parades business. This recipe had already been tested during the Roman Empire period, where the worship of bloody shows in the Colosseum was the protagonist of the entertainment of the citizens of Rome.B. Kitsch in the Arts1. Kitsch and architectureArchitecture is a "polypathic" art that has suffered the consequences of amputation of the aesthetic thought of its creators. More specifically, the church of Aghia Fotini (fig. 14), which is located directly opposite the archaeological site of Ancient Mantineia in the area of Tripoli, was built in 1972 by the Mantinean League. Two structures of classical origin were erected on the outside of the main temple. This is the "Iroon" (fig.15), dedicated to all those who gave their lives for their homeland and their origin was from Mantineia, and the "Jacob's Well" (fig.16) that attributes the meeting of Jesus with Samaritan, which was built to the west of the main temple. The coexistence of the buildings in the same place "provoke" the visitor's aesthetics! | Figure 14. Aghia Fotini in Mantineia (Source: www.lifo.gr) |

| Figure 15. Agia Fotini in Mantineia, "Iroon" (Source: www.lifo.gr) |

| Figure 16. Agia Fotini in Mantineia, "Jacob's Well" (Source: www.lifo.gr) |

In figure 17 we see a building built near the sea in which we find stone lining, wooden balconies with metal decorative additions, gypsum lions at the entrance and neoclassical small columns, elements that reveal a fully "documented" kitsch proposal. | Figure 17. Building (Source: www.lifo.gr) |

Another kitsch architectural proposal is the original facade of a boat-shaped structure (Fig.18), but with Myron's disc thrower in a role as a footballer preparing to kick the ball (Fig.19a). | Figure 18. Ship-shaped construction (Source: www.lifo.gr) |

| Figure 19a. "The discus thrower of Myron" (Source: www.lifo.gr) |

A lot has been said about the architectural aesthetics in Limassol Marina (Figure 19b) of Cyprus. Disparate elements from different historical periods and varying rhythms (Byzantium, gothic, romantic, Cycladic, Ottoman, Art Deco etc.) are a backdrop with a strong element of exaggeration and sophistication. The scenographic proposal complements a set of cafes and restaurants. | Figure 19b. "Limassol Marina, Cyprus" (Source: http://www.cy-arch.com/sovarofaneia-tou-kitsch-limassol-marina/) |

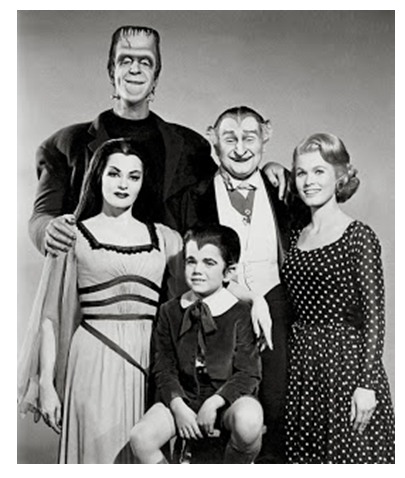

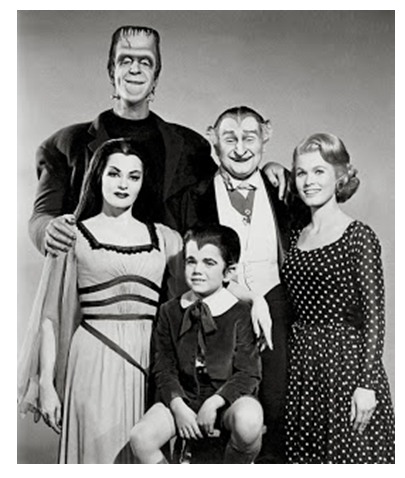

2. Kitsch and cinemaThe Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar (born in 1949) moves in the field of kitsch aesthetics through the use of scenery, clothes, framing, but also emotions, often jumping between melodramatic and ridiculous. Almodóvar uses human weakness and human destiny to the limit that the mockery can start.In Almodovar's films, kitsch is an integral part of modern reality, having acquired its own devotees and its own life-style proposition. In the film "Everything for my mother", the leading actress meets her husband, who has become transsexual, after years, and he appears to be wandering in Barcelona with a nun who has HIV. This is a cinematic approach where it aims to sabotage the enthusiasm and hypocrisy of the representatives of religion while at the same time, through realistic scenes of sadomasochistic and homosexual orgies, to highlight and condemn the most extreme social phenomena and taboos. Hard scenes of rape, masturbation, and sexual release are the focus of his aesthetic pursuits through the art of cinema.The term “camp” is used as an adjective in movies and TV shows that are kitsch. Many of the television shows that took place in the 1950s and 1960s belong to this category. More specifically: The Munsters (Fig. 20), The Adams family (Fig. 21), Batman and Robin (Fig. 22). | Figure 20. Munsters (Source: http://www.neatorama.com/2015/07/27/28-Facts-You-Might-Not-Know-about-The-Munsters/) |

| Figure 21. The Adams family (Source: http://ngradio.gr/news/diaskedasi/pos-einai-simera-oikogeneia-adams/) |

| Figure 22. Batman and Robin (Source: https://soso.bz/Yx49Kv) |

3. Kitsch, politics and cartoonMany cartoons related to kitsch offer laughter and sarcasm, coming from Greek and foreign artists, who do not hesitate to satire symbols and people to show the desperation of the Greek, but also to emphasize the absurdity of contemporary socio-political life. And as we see, representatives of this power imposed on Greece in this absolute way are Germany with Chancellor Angela Merkel, the International Monetary Fund, the so-called IMF, and the Troika. Thus, the Brazilian cartoonist Carlos Latuff creates a work where the comparison of Merkel to a Roman emperor, with sandals, robe and the traditional Roman wreath made up of the stars of the EU, implies the monarchy and the decline that we associate with the time of the Roman Empire. The Greek citizen is presented as a victim of the regime, incapable of doing something to resist (fig. 23). | Figure 23. Carlos Latuff-untitled, (2010) (http://www.instabam.gr/asteia/astia-skitsa-apo-tin-elliniki-ikonomia-ke-tin-krisi-ikones/) |

In Latuff's next cartoon (fig. 24), we see a relative satirical criticism, which again does not deny the existence of power but reveals it as implausible and accuses it as being hostile. Instead of Nazi tanks, there is a limousine that represents foreign interests. In both cases, the Greek citizen is presented as a victim, unable to do anything, but on the other hand, he does not present himself as a victim who accepts his fate but sees what is happening and gets annoyed. | Figure 24. Carlos Latuff - Untitled, (2010) (http://www.libanovivo.org/tag/resolution) |

Such treatment of Greek politicians, regardless of party, - as responsible for the sacrifice of the Greek people - is presented in many cartoons. Panos Marangos's cartoon (2013) depicts the former Minister of Administrative Reform and e-Government, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, as a Roman emperor in a place reminiscent of the Roman Colosseum, having fun with the liberation of the beast of unemployment against people (fig.25). The Greek people are again the victim, unable to save themselves and remain untouchable, since the implementation of this specific policy has removed the possibility of work, which is necessary so that they preserve their identity. But politicians here are not portrayed as marionettes of external power, but as power itself. | Figure 25. Maragkos. untitled, (2013) (http://www.iefimerida.gr/news/126155/%CE%B7-%CE%BF%CE%BA%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%BF%CE%BC%CE% B9% CE% BA% CE% AE-% CE% BA% CF% 81% CE% AF% CF% 83% CE% B7-% CE% BC% CE% AD% CF% 83% CE% B1-% CE % B1% CF% 80% CF% 8C-% CF% 84% CE% B1-% CF% 83% CE% BA% CE% CF% 89% CE% BD-% CE% B3% CE% B5% CE% BB% CE% BF% CE% B9% CE% B3% CF% 81% CE% % BD-% CF% 80% CF% 89% CF% 82-% CE% B1% CE% BD% CF% 84% CE% B9% CE% BB% CE% B1% CE% BC% CE% B2% CE % AC% CE% BD% CE% BF% CE% BD% CF% 84% CE% B1% CE% B9-% CF% 84% CE% B7% CE% BD-% CE% BA% CE% B1% CF % 84% CE% AC% CF% 83% CF% 84% CE% B1% CF% 83% CE% B7-) |

But there are cartoons that clearly use carnival rhetoric, where we see Greek politicians becoming vulnerable through ridicule. Let us look at, for example, the cartoon that presents former Prime Minister G. Papandreou as a discus thrower (figure 26), in a similar position with the Myron's statue (in order to depict Greece) and also as enslaved. His bindings are economic. The athlete's disc, which keeps him tied, is the Euro, the currency of the EU. In the left hand, the other bond is the International Monetary Fund. | Figure 26. Unknown Creator, Untitled, (2011) (http://antiparatheseis1.blogspot.gr/2011_02_01_archive.html) |

Another example is the Latuff's cartoon, which was published in the Brazilian Opera Mundi as a reaction to aggressive neo-Nazi behavior towards Greece (2012) and which resists the imposition of a fascist identity on an entire country. | Figure 27. Latuff. untitled, (2012) (http://el.globalvoicesonline.org/2012/10/15162) |

Here we see a man lifting the weight of the Greek crisis and the Euro. The way of his depiction, with the shaven head, brings to mind a prisoner, a gravestone, who is training with weights, while the swastika, which is revealed instead of the biceps, clearly depicts him as a (neo) Nazi. The striped t-shirt, at the same time, is the Greek flag and the biceps implies that the power to resolve the crisis is (neo) Nazism.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, we can identify kitsch as an integral part of modern reality, also distinguishing its rapid expansion into contemporary socio-political and cultural reality. Of course, this fact is directly related to the evolution of the internet and the uncritical posting of images and texts where kitsch acquires a dangerous "glamor", continuing to be a form of manipulation involving intimate and easily understood forms of art.In addition, we have shown that architecture is a "polypathic" art that has suffered the consequences of amputation of the aesthetic thought of its creators, which is found in the constructions we described in a previous chapter.Finally, through the interactive relationship of aesthetics and society, we showed kaleidoscopically that this relationship is not so innocent, since in periods of totalitarian regimes the aesthetics are determined and imposed by the respective authority, so there is no free and healthy interaction in its contact with the citizens of these regimes. Within such a morbid, politically, environment, the aesthetic criterion of mass is formed, entirely connected to the vehicle that the dictator imposes, totally militant and manipulated by his suggestions and desires.

References

| [1] | McBride, P. C. (2005). "The Value of Kitsch, Hermann Broch and Robert Musil on Art and Morality," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 29: Iss. 2, Article 5. |

| [2] | Lugg, C.A. (1998), "Political Kitsch and Educational Policy", American Educational Research Association. San Diego, April 14. |

| [3] | Lugg, C.A. (1998), "Political Kitsch and Educational Policy", American Educational Research Association. San Diego, April 14. |

| [4] | Kundera, M. (1999). The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Athens: ESTIA. |

| [5] | Adorno, Th. (1996). Dialectics of Enlightenment. Athens: Island. |

| [6] | Greenberg, Cl. (1961). Art and Culture. Boston: Beacon Press. |

| [7] | Baudelaire, Ch. (2018). The Painter of Modern Life, Athens: Papadopoulos. |

| [8] | Domus Aurea was a huge shaped palace built by Emperor Nero in the heart of ancient Rome, as the great fire of ‘64 AD. had destroyed much of the city and the noble villas on the Palatine hill. |

| [9] | Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena, (1470-1520), Italian cardinal and dramatist. Source: wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernardo_Dovizi_da_Bibbiena. |

| [10] | Connelly, F. S. (2012). The grotesque in Western art and culture: the image at play. New York: Cambridge University Press. |

| [11] | Boyvin, R. (1525-1598), French engraver who lived in Angers. Source: .wikipedia.org / wiki / René_Boyvin. |

| [12] | Cornelis, B. (1506 / 10-1555), Flemish engraver and publisher. Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornelis_Bos. |

| [13] | Connelly, F. S. (2012). The grotesque in Western art and culture: the image at play. New York: Cambridge University Press. |

| [14] | Connelly, F. S. (2012). The grotesque in Western art and culture: the image at play. New York: Cambridge University Press. |

| [15] | Connelly, F. S. (2012). The grotesque in Western art and culture: the image at play. New York: Cambridge University Press. |

| [16] | Connelly, F. S. (2003). Modern art and the grotesque. New York: Cambridge University Press. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML