-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Arts

p-ISSN: 2168-4995 e-ISSN: 2168-5002

2019; 9(2): 27-40

doi:10.5923/j.arts.20190902.01

Design; Beauty and User Satisfaction

Sara Ebrahimi, Ali Asghar Fahmifar

Department of Art Study, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Sara Ebrahimi, Department of Art Study, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study was about the relationship between product aesthetics and user satisfaction in some of user based design methods (UCD, KE, UX, and PD). Also we tried to know how beauty will appear in the product and perceived by users, and how can beauty result in user satisfaction by mentioned methods. So, we introduced some new models about beauty in the product and the way which user satisfaction is generated. According to these models, some of the methods with emotional approach were about to have more consideration to the perception of form in beauty and generating pleasure for satisfaction, and those with experimental approach, have focused on the experience of more function and less form in users’ mind and then the satisfaction would be generated of fulfillment of expectations. Furthermore we discussed that satisfaction has two general types; beauty in the products would have different meanings in each level.

Keywords: Design, Beauty, Aesthetics, User satisfaction, User based design methods

Cite this paper: Sara Ebrahimi, Ali Asghar Fahmifar, Design; Beauty and User Satisfaction, International Journal of Arts, Vol. 9 No. 2, 2019, pp. 27-40. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20190902.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Throughout history, numerous definitions of beauty have been raised, whether in the context of its objective or subjective, whether it is in terms of its usefulness, its intrinsicity, etc. In some cases, these discussions have been presented with pleasure and the beauty ratio has been reviewed with pleasure and enjoyment. But will pleasure and beauty also bring satisfaction? Which standards satisfaction has and how can we be sure about reaching them? On the one hand, in the course of history, different methods have been developed for product design; Part of these methods followed goals such as sales and intellectual practices of the designer or group of designers. And partly they were looking for scientific methods of design. In the scientific design process, focus has been on things such as market, production, environment, user, and so on. In the meantime, the attention paid to the user in recent years is more than the other, which has focused its ultimate goal on satisfying the user both at the time of choosing a product and after using it. The issue raised here is how well these user-based design methods can provide the beauty they expect. So can a new and comprehensive definition of beauty in products be presented?The main purpose is to investigate the relationship between product aesthetics and user satisfaction in some of user-based design methods and to provide a new and comprehensive definition of beauty in products or from the perspective of product users if possible. Research questions which will be answered by this research are:What is the relationship between user satisfaction and beauty in the product?How will beauty appears in the product and perceived by users?How can beauty result in user satisfaction by user based design methods?

2. Background

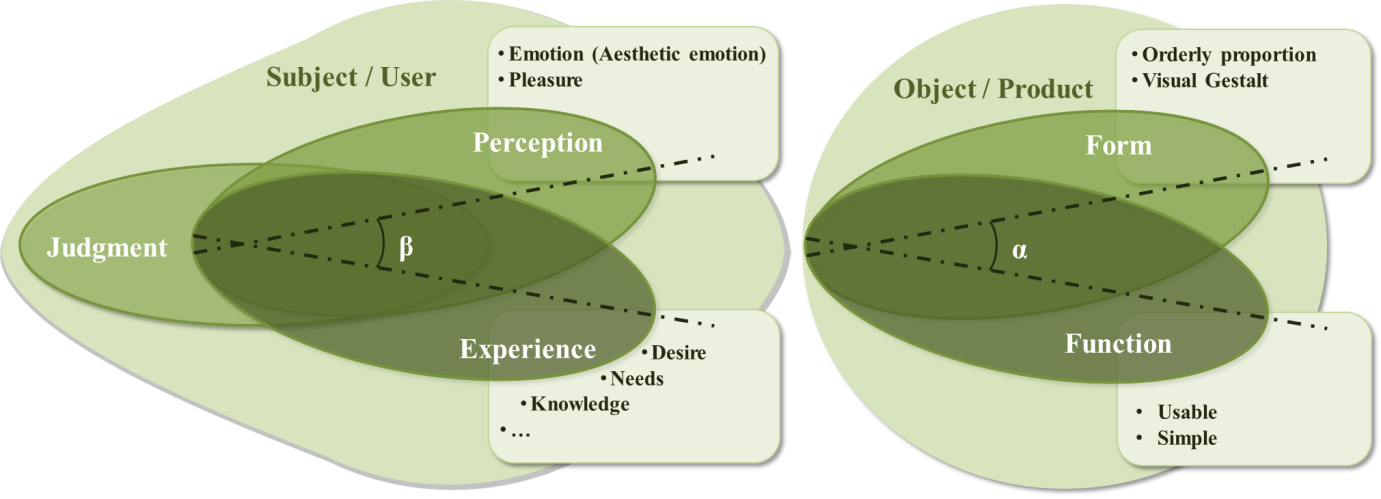

- So many studies discussed about the history of beauty definition through ages, among those, by Frohlich [14], Karvonen [24] and Tractinsky [47], Table 1. shows an overview of these definitions classified by the time and its founder.

|

3. Materials and Methods

- This is a descriptive and analytical study which has a critical and comparative view to some of user based design methods (User centered design, Kansei engineering, User experience and Positive design). Beauty definitions, satisfaction properties and identified design methods’ processes are the raw materials of the study. So, the study will have three parts: Beauty, Satisfaction and Design.

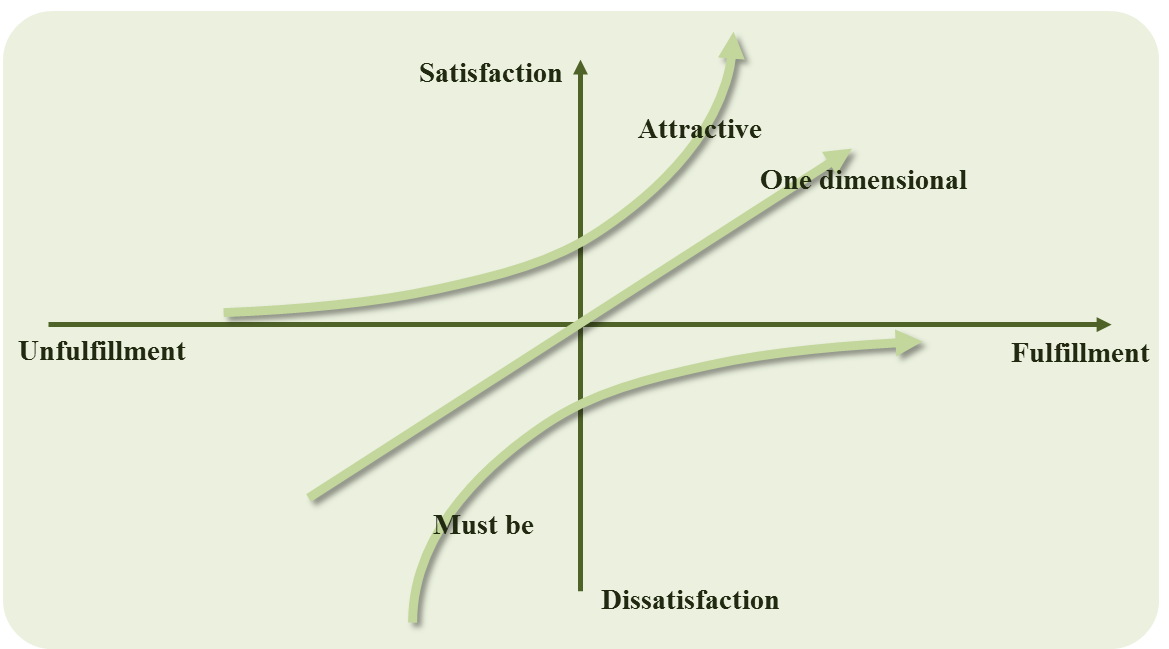

4. Beauty

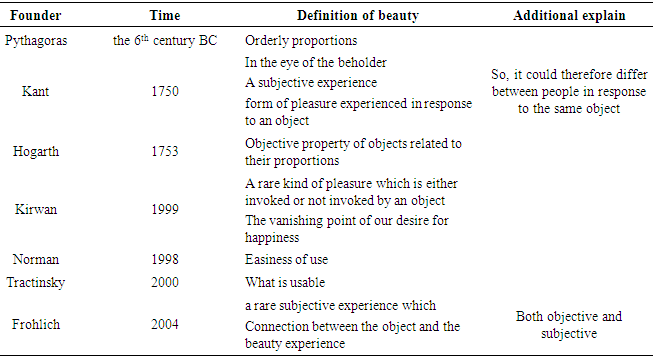

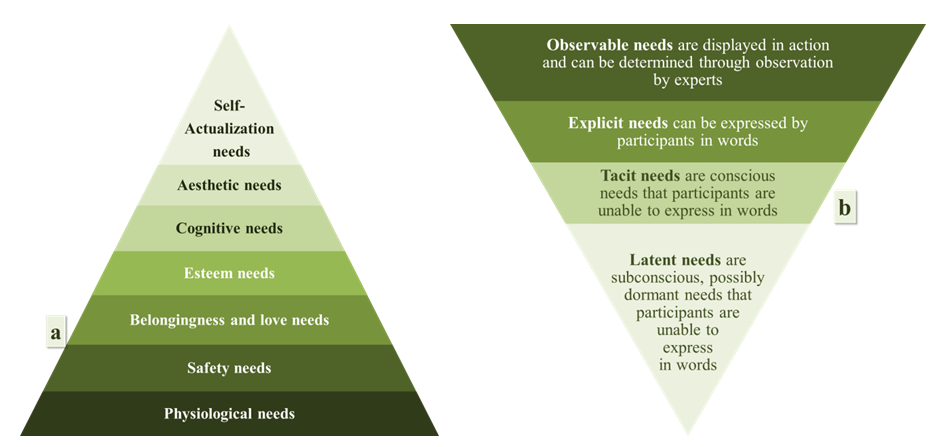

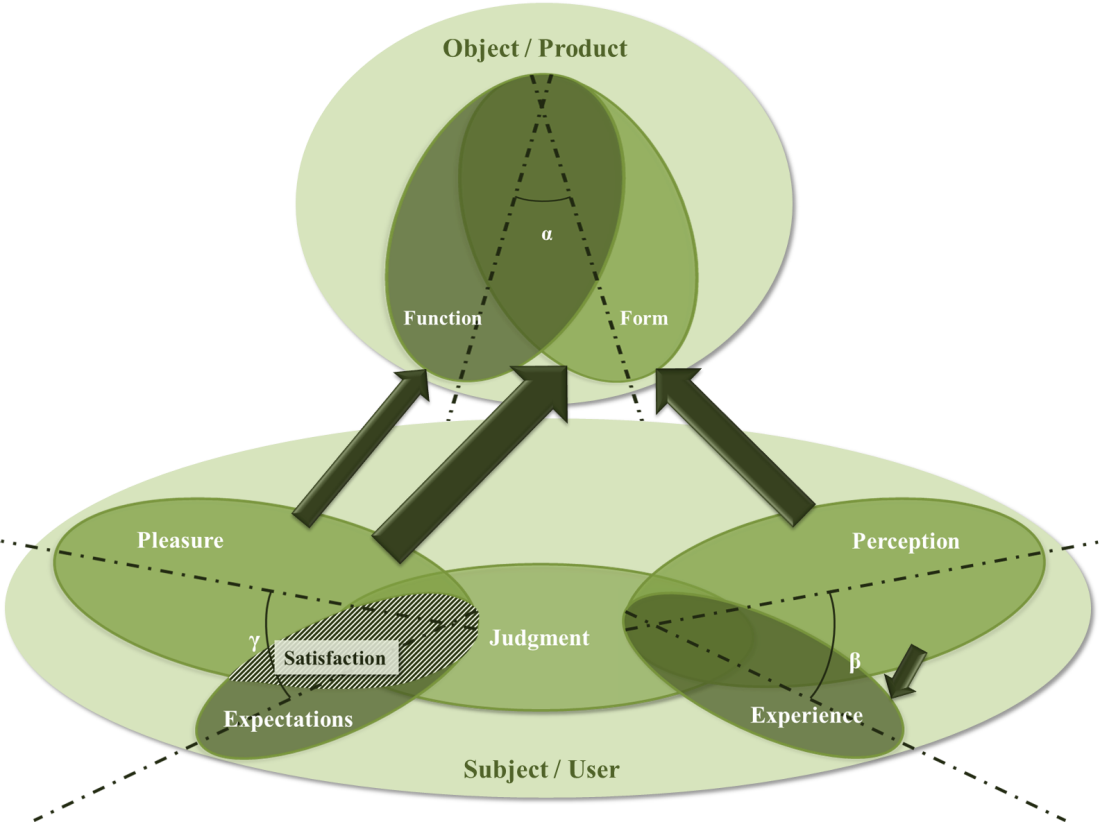

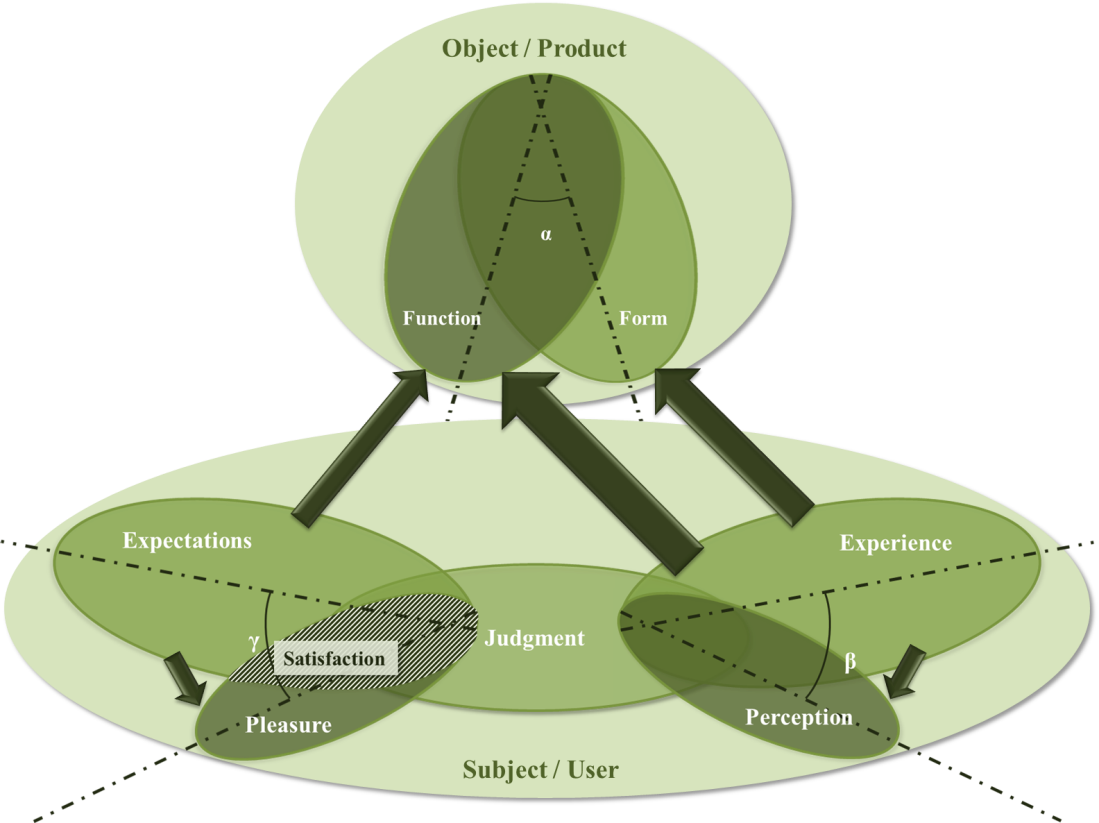

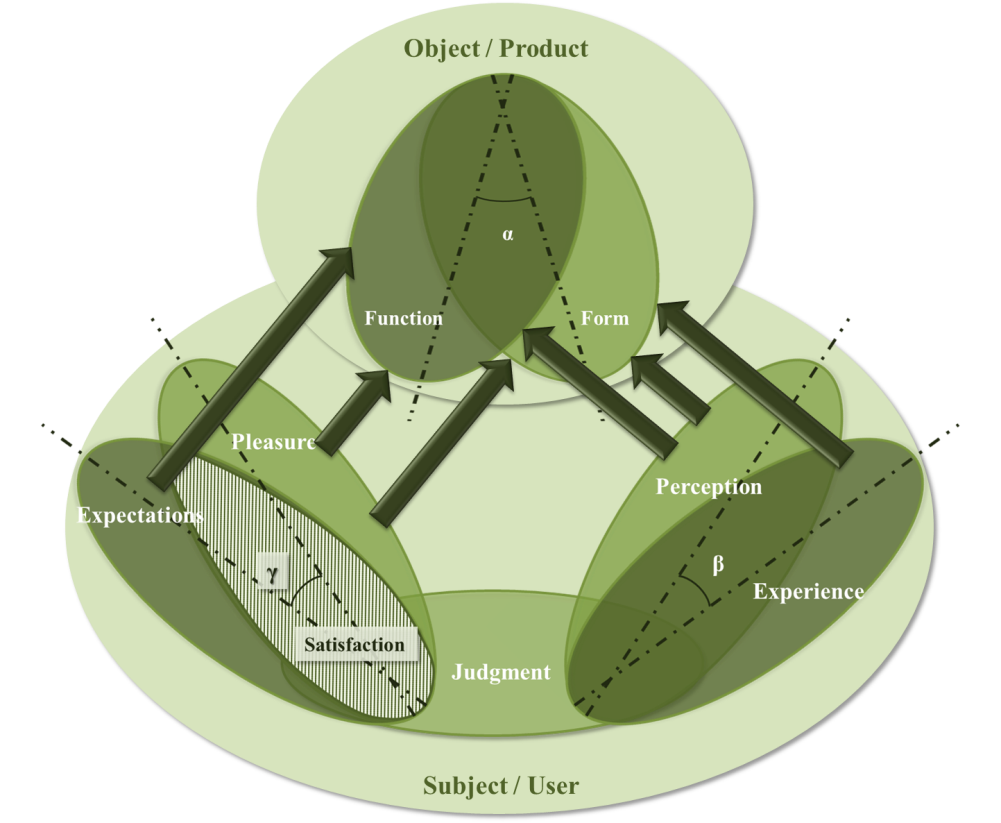

- Aesthetics is variously defined as beauty in appearance, visual appeal, an experience, an attitude, a property of objects, a response or a judgment, and a process [31]. Beauty is a very old topic in philosophy. Early writers proposed that beauty was an objective property of objects, while later writers suggested that it was more of a subjective experience triggered by objects. This debate continues today around the issue of taste in judgments of beauty, and whether or not there is such a thing as good taste in recognizing beauty to be found in the world [14].Aesthetics originate from the theory of art and usually refers to beauty and more specifically, to the beauty of art [45]. In the context of a metaphysical consideration of the world’s order, beauty is equated with its orderliness [Tractinsky’s “classical aesthetics” and property of objects]. In the epistemological context derived from Baumgarten, beauty is thought of as adequacy to the mind in perception [Hassenzahl’s “goodness”, inside the viewer’s head]. From the anthropological point of view it may seem to be nothing more than sensual attractiveness [Berlyne’s work on arousal; Norman’s [59] notion of “visceral emotion”] [31]. It is an absolute and a part of “the big three”; the beautiful, the good and the true [39]. Beauty illuminates, attracts, persuades, deceives and represents harmony, freedom, symmetry and proportion [45].Aesthetics usually refers often to non-quantifiable, subjective, and affect-based experience of system use; usability is commonly measured by relatively objective means and sets efficiency as its foremost criterion [2], [47].The tension between form and function has long been at the crossroad of artifact design. Whereas emphasis on function stresses the importance of the artifact's usability and usefulness, accentuating the artifact's form serves more the aesthetic, and perhaps social, needs of designers and customers. Until the first quarter of this century, the design of commodities and mass production artifacts were quite devoid of aesthetic considerations. Petroski (1993) credits two industrial design pioneers, Loewy and Dreyfuss, with the introduction of aesthetic considerations to mass production and with the development of industrial design as an explicit marketing instrument. Evidently, aesthetics considerations gained importance quickly. About half a century later, Norman (1988; 1992) laments the appropriation of modern design by designers who place aesthetics ahead of usability. Similar sentiments concerning designers' priorities can be found in various areas of artifact design [47]. Aesthetics can be seen as an aspect of the broader concept of user experience, which can include usability, beauty, overall quality and hedonic, affective and experiential aspects of the use of technology [49]. Aesthetics is seen to have something to do with pleasure and harmony that human beings are capable of experiencing [31]. Lenz et al. [28] suggested a principle of an aesthetic interaction is the “fit” between interaction attributes and appropriate experience (p. 88).Beauty is perceived immediately – it takes effect on product perception and evaluation right from the first glimpse [12]. Beauty in an interactive product might also indicate increased usability [18].To the extent that aesthetics is a pleasant experience or an experience that leads to pleasure, it implies a relationship to emotion [31]. Desmet [9] classified product emotion in surprise emotions (e. g. surprise, amazement), instrumental emotions (e. g. disappointment, satisfaction), aesthetic emotions (e. g. disgust, attracted to), social emotions (e. g. indignation,, admiration), and interest emotions (e. g. boredom, fascination) (p. 6). Even if aesthetics is a property of objects, when confronted with an object of beauty, it does evoke a positive emotional experience in the viewer [31]. Products and services need a balance between pragmatic (e.g., usability) and hedonic quality (e.g., novelty) [53]. Aesthetic design can enhance the desirability of a product and greatly influence customer satisfaction in terms of perceived product quality [5].Hassenzahl [17] defined a judgment of beauty as “a predominantly affect-driven evaluative response to the visual Gestalt of an object”. Beauty is evaluated from the way the design is experienced in the user’s mind and is in interaction between the user and the artifact, i.e., as a quality of the interplay [29]. The term design aesthetics is employed in two ways: it may refer to the objective features of a stimulus (e.g. colour of a product) or to the subjective reaction to the specific product features [43].According to the definitions of beauty hitherto, authors introduce a model that shows the area of beauty in products. As shown in figure 1. we have two main parts: Object or product and subject or user. Both of them can effect on beauty of the thing.

| Figure 1. Schematic view of beauty area in products (source: authors) |

5. Satisfaction

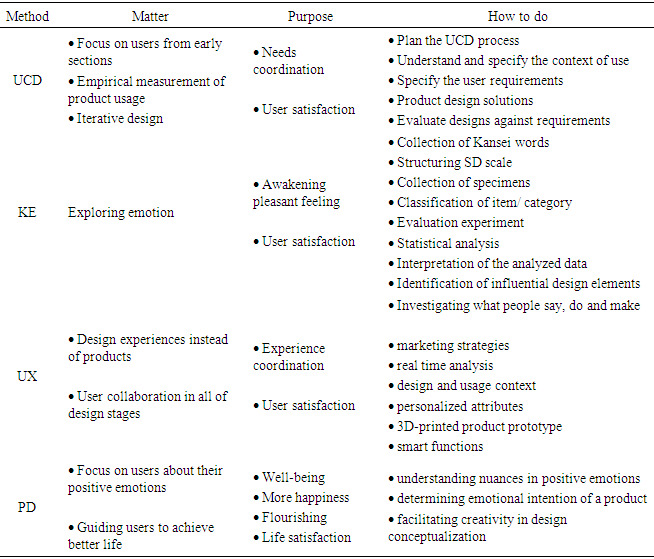

- Customer satisfaction is the major concern and prerequisite for competitiveness in today’s global market [5]. Oxford online dictionary [64] explained satisfaction as “fulfillment of one’s wishes, expectations, or needs, or the pleasure derived from this”, also Cambridge online dictionary [63] defined it as “a pleasant feeling that you get when you receive something you wanted, or when you have done something you wanted to do”, and “the act of fulfilling (= achieving) a need or wish”.The judgment of how satisfied people are with their present state of affairs is based on a comparison with a standard which each individual sets for him or herself; it is not externally imposed. It is a hallmark of the subjective well-being area that it centers on the person’s own judgments, not upon some criterion which is judged to be important by the researcher [13].If you are creating the product for use in your organization, you will want users to be more productive and satisfied [6]. User satisfaction is a statement about, or a judgment of, the user experience [31]. When systems match user needs, satisfaction often improves dramatically [6]. Satisfaction is an emotional consequence of goal-directed product use [18], [20]. Satisfaction may be a by-product of great usability in traditional office environments, and that satisfaction can be defined in terms of efficiency and effectiveness [32].As stated by the ISO 9241-11 standard, user satisfaction is supposed to contribute to usability along with effectiveness and efficiency [32]. There, ‘user satisfaction’ is referred to in terms of ‘attitude’ and ‘degree of comfort’ and measured by a number on a 7- or 10-point scale [31]. Hansemark and Albinson [58] explained that “satisfaction is an overall customer attitude towards a service provider, or an emotional reaction to the difference between what customers anticipate and what they receive, regarding the fulfillment of some needs, goals or desire” [1].The intensity, positive or negative, of the first impression is likely to set the scene for the amount of attention subsequently paid to experiential usability and pleasure-of-usage factors, which then culminate in that judgment of the experience that we might call user satisfaction [31]. Courage and Baxter [6] defined usability as the effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction with which users can achieve tasks when using a product (p. 747), while Maguire [59] explained the satisfaction as user comfort and acceptability (p. 603). In order to widen the notion of user satisfaction beyond efficiency and effectiveness of the user experience, researchers must start to think of usability as part of a satisfying user experience [32]. User satisfaction is a complex construct that incorporates several measurable concepts and is the culmination of the interactive user experience [31]. In HCI the term satisfaction is often used synonymously with perceived usability or at least with the overall evaluation of a product [18]. User satisfaction is a judgment about the interactive experience with products [31].Furthermore life satisfaction refers to cognitive, judgmental process. Shin and Johnson (1978) defined life satisfaction as “a global assessment of a person’s quality of life according to his chosen criteria” [13].Kano et al. (1984) developed a two-dimensional model to explain the different relationship between customer satisfaction and product criterion performance. The Kano model classifies product criteria into three distinct categories, as shown in Figure 2. Each quality category affects customers in a different way. The three different types of qualities are explained as follows:1. The must-be or basic quality: Here, customers become dissatisfied when the performance of this product criterion is low or the product attribute is absent. However, customer satisfaction does not rise above neutral with a high-performance product criterion.2. One-dimensional or performance quality: Here, customer satisfaction is a linear function of a product criterion performance. High attribute performance leads to high customer satisfaction and vice versa. 3. The attractive or excitement quality: Here, customer satisfaction increases super linearly with increasing attribute performance. There is not, however, a corresponding decrease in customer satisfaction with a decrease in criterion performance [5].

| Figure 2. Kano model of customer satisfaction [55] |

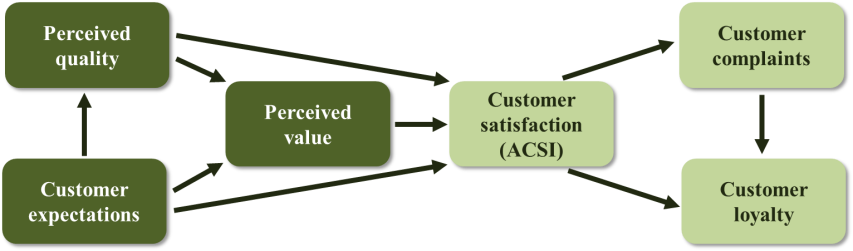

| Figure 3. American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) model [1] |

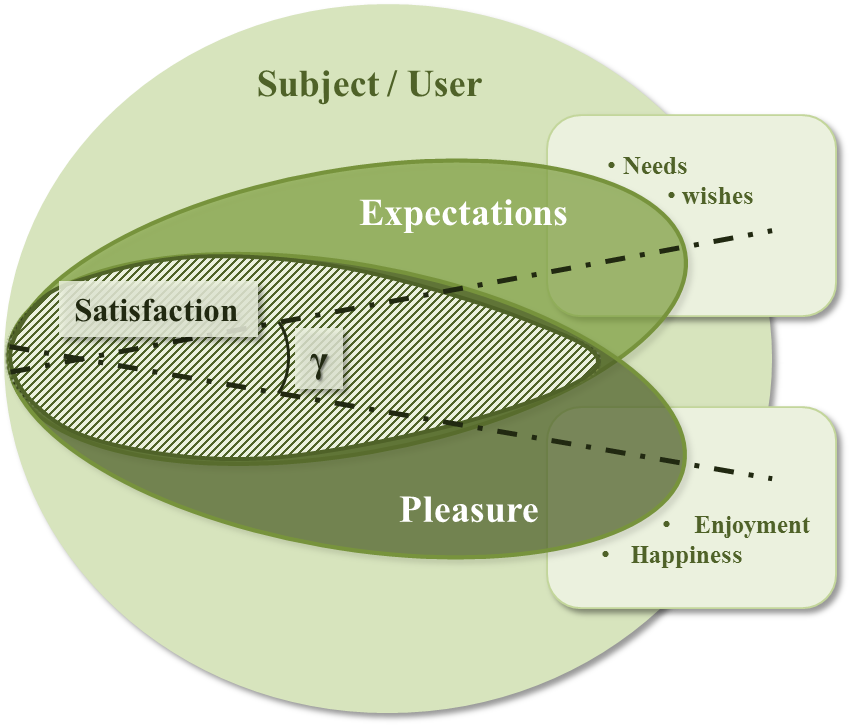

| Figure 4. New satisfaction model with two main elements; expectations and pleasure (Source: authors) |

6. Design

- Product design is a problem-solving activity, whose purpose is to develop a successful product fitting consumers’ needs. To achieve this goal, systematic methods have been used by designers to obtain an optimal solution through the process of data collection, analysis, synthesis and decision-making [22]. The trend of product development is becoming toward the consumer-oriented, namely the consumer’s feeling and needs are recognized as invaluable in product development for manufacturers [34]. User based design methods are abundant, like User centered design, emotional design, user experience, etc. Here four of user based design methods will be discussed; what they are, what is their main purpose, and how they are used.

6.1. User Centered Design

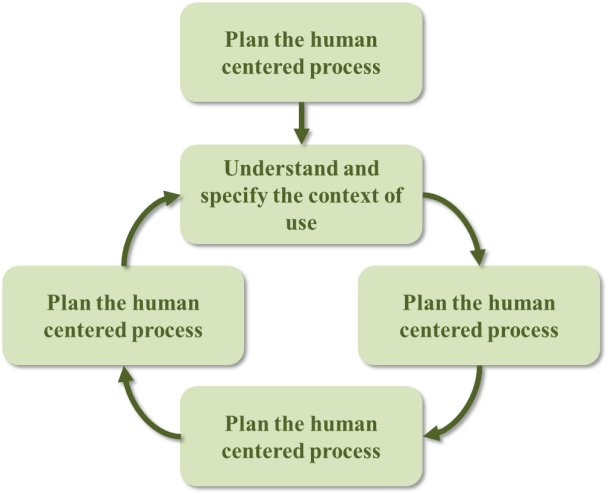

- User requirements refer to the features/attributes your product should have or how it should perform from the users’ perspective. User-centered design (UCD) is a discipline for collecting and analyzing these requirements [6]. Furthermore, UCD is a general term for a philosophy and methods which focus on designing for and involving users in the design [61], and is a product development approach that is concerned with the end users of a product and the philosophy is that the product should suit the user, rather than making the user suits the product [6].UCD allows users to participate throughout the design process of a product that will fulfill the demands of the user and improve the usability of the product. Brown and Mulley’s research demonstrated that UCD shortens overall development time and costs by reducing the number of changes required in the later stages of the design process which results to better quality products [54].The User-Centered Design (UCD) model described by Buurman [3] advocates a design process that involves users in the whole design process in order to match the product to the user requirements and to increase its practical use. The process, unlike the common, technology and market driven model which most products follow, leads to more useful and usable products [54]. Maguire [59] mentioned a cycle for UCD process (from ISO 159 13407) (Figure 5.). It starts with planning the human centered process and continued with the cycle with four main steps: understanding and specifying the context of use, specifying the user and organizational requirements, producing design solutions, and evaluating designs against requirements.

| Figure 5. UCD cycle [59] |

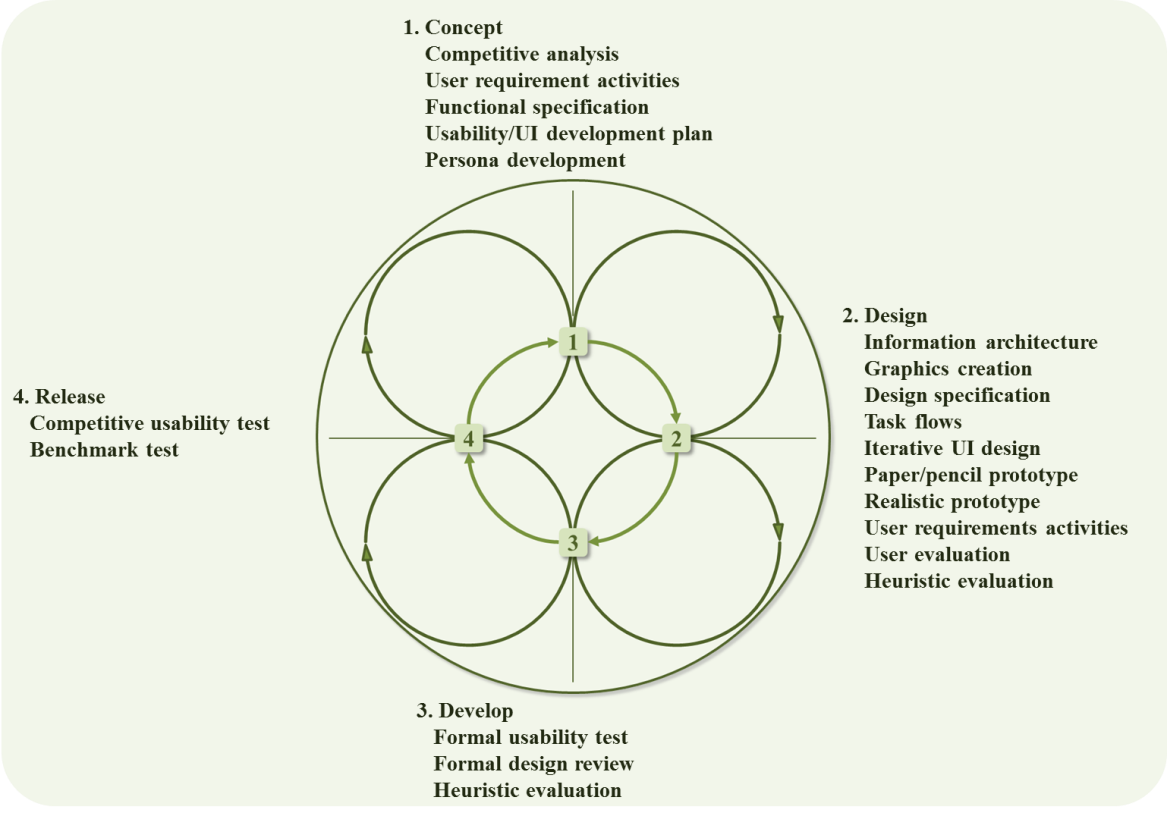

| Figure 6. Product lifecycle with UCD processes incorporated [6] |

6.2. Kansei Engineering

- The Japanese word, Kansei has the significance of feeling, impression and/or emotion [62] and means sensibility, feelings and cognition [23]. When translated into English it might mean ‘consumer’s psychological feeling and image’ [35], [42]. Professor Nagamachi began Kansei Engineering (KE) by combining psychological measurement and analysis methodologies with ergonomic measurement techniques. KE is indispensable for successful product development [23]. KE is a proactive product development methodology, which translates customers’ impressions, feelings and demands on existing products or concepts into design solutions and concrete design parameters; it is mainly a catalyst for a systematical development of new and innovative solutions, but can also be used as an improvement tool for existing products and concepts [42]. KE collects and organizes tools coming from other fields of research (mathematics, computer science, psychology...) in order to evaluate users, impressions [30]. Japanese designers have used KE as a consumer oriented ergonomic technology for developing new products [33].There are six technical styles of KE methods; Type I through Type VI. Type I KE means Category Classification from zero- to nth- category. Type II uses a computer-aided system. Type III utilizes a mathematical framework to reason the appropriate ergonomic design. Type IV refers to KE system constructed by the forward and backward reasoning and Type V combines KE technology with Virtual Reality. Type VI is a new system of Collaborative Kansei Designing System in which the designers apart from each other collaborate to make a new design through an intellectual Internet using the kansei databases [36].A flow of the KE Type I explained by Nagamachi [37] shows that it will start with the decision of strategy, and continues with collection of Kansei words, setting of SD scale the kansei words, collection of product samples, a list of item/category, evaluation experiment, analysis using multivariate statistical methods, interpretation of the analyzed data, explanation of the data to designer(s) and check of designer’s sketch wit KE candidate (p. 2).

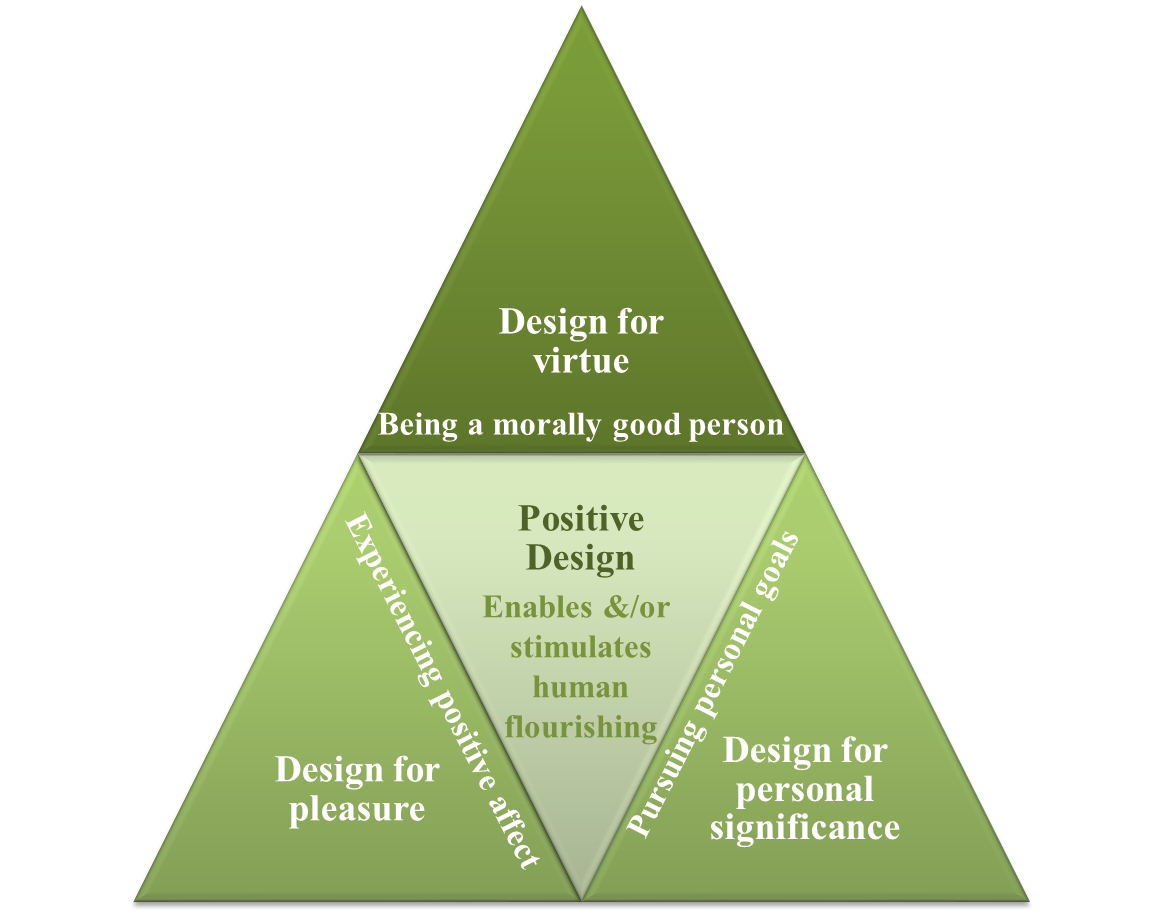

6.3. User Experience

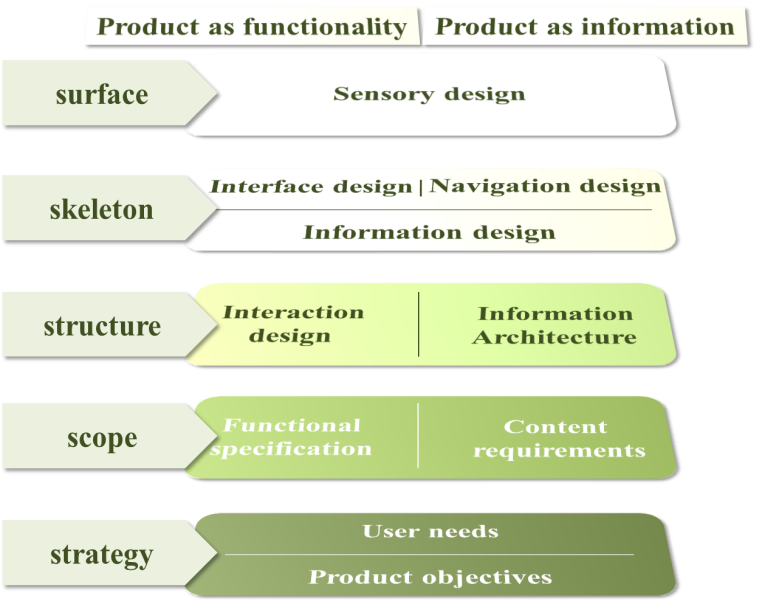

- In the user-centered design process, we are focused on the thing being designed (e.g., the object, communication, space, interface, service, etc.), looking for ways to ensure that it meets the needs of the user. Also, in user-centered design, the roles of the researcher and the designer are distinct, yet interdependent. The user is not really a part of the team, but is spoken for by the researcher [40]. User experience is a change from a user-centered design process to that of participatory experiences. It is a shift in attitude from designing “for” users to one of designing “with” users [40].Design is about user experience rather than about the creation of products [31]. We understand an experience as “an episode, a chunk of time that one went through—with sights and sounds, feelings and thoughts, motives and actions, closely knitted together, stored in memory, labeled, relived, and communicated to others; An experience is a story, emerging from the dialogue of a person with her or his world through action” [19], [21]. The aim of “Experience Design” is to design users’ experiences of things, events and places [40]. There is a common understanding that UX is holistic – it emphasizes the totality of emotion, motivation, and action in a given physical and social context – and that it is subjective – focusing on the “felt experiences” rather than product attributes [53]. People can tell whether their experience had been positive or negative (i.e., affectivity) [21].“Needs” would set the stage for Experience Design [21]. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is shown in Figure 7 a. By explicitness of the needs, Sanders [40] had showed another pyramid that classifies these needs into 4 levels (Figure 7 b.).

| Figure 7. (a) Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, (b) levels of need expression [40] |

| Figure 8. 5 levels of UX [15] |

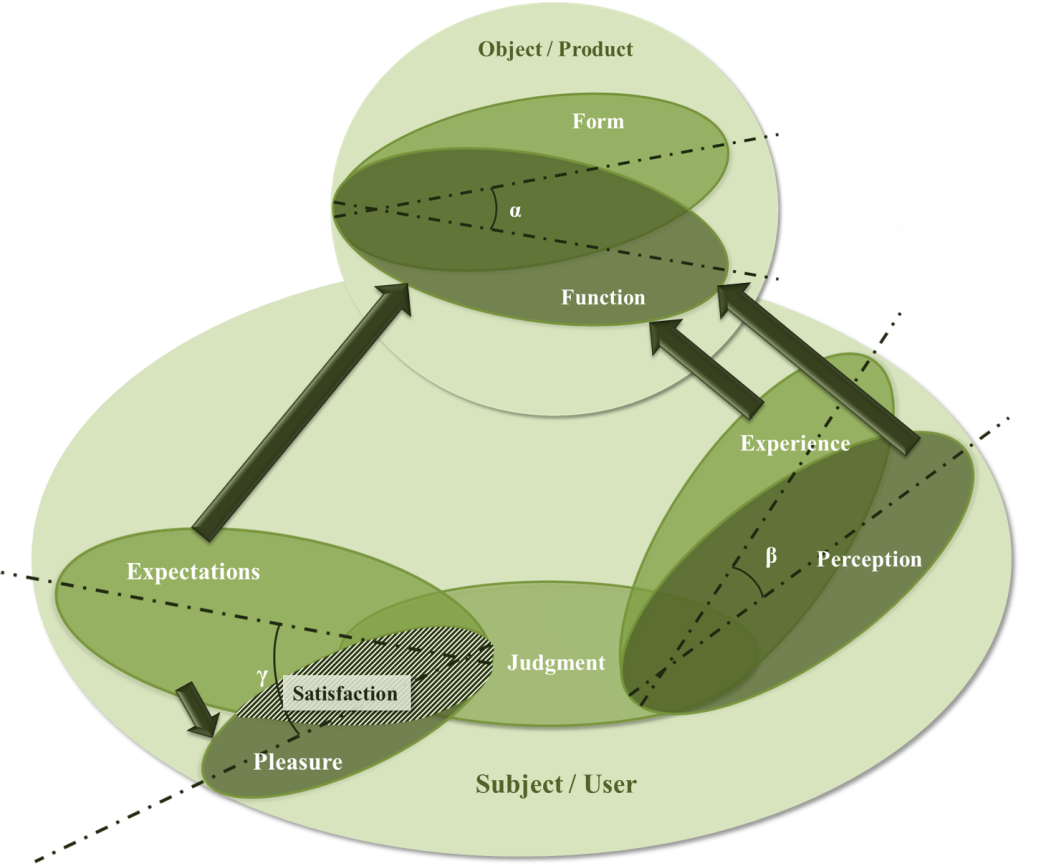

6.4. Positive Design

- Positive design (PD) follows subjective well-being which based on positive psychology [10], [11]. At the end of 20th century and primary years of current century Positive psychology was raised by Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi to focus on mental health rather than mental illness [52]. Seligman [41] said that design, entertainment and technology can increase positive emotion and happiness in people. So, PD translates the elements of wellbeing and strategies that support the pursuit to live not only a good – but also a fulfilling life which into actionable design solutions [38].Numerous studies have confirmed that it is not personal resources that make a person happy, but rather how those resources are exploited [11]. PD initiatives deliberately intend to increase people’s subjective well-being and, hence, increase an enduring appreciation of their lives. The PD framework combines three key components of subjective well-being (Figure 9.) [11].

| Figure 9. Positive Design (PD) framework [11] |

6.5. An Overview of the Methods

- As stated about four of different kinds of user based design methods, here the outline of each method are presented to have a better overview of them in Table 2.

|

7. Discussion

- Due to the models that suggested by authors for beauty (Figure 1.) and satisfaction in the products (Figure 4.), we can find a relation between each of mentioned design methods with satisfaction and beauty in products. Figure 10. shows this relation about UCD method.

| Figure 10. Relation between beauty and user satisfaction in UCD method (source: authors) |

| Figure 11. Relation between beauty and user satisfaction in KE method (source: authors) |

| Figure 12. Relation between beauty and user satisfaction in UX method (source: authors) |

| Figure 13. Relation between beauty and user satisfaction in PD method (source: authors) |

8. Conclusions

- This study was about the relationship between product aesthetics and user satisfaction in some of user based design methods (UCD, KE, UX, and PD). To get this purpose we tried to introduce some new models about beauty in the product and user satisfaction. Also we tried to know how beauty will appear in the product and perceived by users, and how can beauty result in user satisfaction by user based design methods. So we introduced some new models about beauty in the product and the way which user satisfaction is generated. According to these models, we could show how beauty and satisfaction in relation to each other will connect to each of mentioned methods. The results show that beauty which will arise from UCD is about function of the product and experiences in users’ mind and the satisfaction will be generated of fulfillment of users’ expectations. In KE, perception of form awakens emotion and makes good experiences (beauty) and satisfaction would be about the pleasure which users find more in the form and less in function of the product. UX tries to make good experiences of product form and function, and this would have effect on users’ perception. Also satisfaction in this method would be about fulfillment of expectations which will result in pleasure of users. In PD method there would be more connection among pointed factors; both perception and experience about form and function of the product are active and in other part, both of the fulfillments of expectation and pleasure would have effect on satisfaction.Furthermore we discussed that satisfaction has two general type, short term satisfaction and long term satisfaction, and the short term one has two levels, primary satisfaction and afterward satisfaction. Beauty in the products would have different meanings in each of these types and levels. In primary levels it would more about form and its perception, and the more we go ahead, it would be about function and its experience.Moreover, according to Kano model, beauty can be considered in one dimensional and attractive quality, which would be result in more and more satisfaction of the products. It seems that both form and function are important in these two kinds of quality and perception and experience of them also are consequential.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML