-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Arts

p-ISSN: 2168-4995 e-ISSN: 2168-5002

2016; 6(1): 21-35

doi:10.5923/j.arts.20160601.03

Manifestations of Shiite Thoughts in the Architecture and Decorations of Soltaniyeh Dome

Robab Faghfoori 1, Hasan Bolkhari Ghehi 2

1PhD Student, College of Art and Architecture, Imam Reza International University, Mashhad, Iran

2Associate Professor of University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Robab Faghfoori , PhD Student, College of Art and Architecture, Imam Reza International University, Mashhad, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Islamic Art and Architecture is influenced by cosmological foundations of Islam and also a reflection of religious and spiritual facts. An example of religious-burial architecture in Ilkhani era is Soltaniyeh Dome located in Soltaniyeh town, Zanjan province, northwest of Iran. Evidence supports the fact that Sultan Mohammad Khodabandeh — the founder of the dome —was under the impression of Shi’a visions and beliefs, when spacing and making ornaments. The main purpose of this research is recognition of Shiite principles dominating design and ornaments of this huge historical monument. One such principle is the belief that there are 12 successors to the holy prophet who continue his teachings among people after his passing. Research findings show that the Contents of epigraphs, precise appropriateness of ornaments, and symbolic and overt language of sacred geometry of this huge monument clearly reflect that the Shia believe in Imamate principle, justice and its inner and interpretative attitude toward affairs of all kind. Implementing some certain numbers in geometrical figures and using different shades of green and blue colours reflect Shiite spirituality and mental unity of architectures and artists of this work with underlying principles of this religion.

Keywords: Islamic architecture, Soltaniyeh Dome, Principles of Shiite thought, Decorative ornaments, Ilkhani era

Cite this paper: Robab Faghfoori , Hasan Bolkhari Ghehi , Manifestations of Shiite Thoughts in the Architecture and Decorations of Soltaniyeh Dome, International Journal of Arts, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 21-35. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20160601.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Islamic architecture is an art rooted in Islamic school with its body based on beliefs, wisdom, and mystic issues. It can be deemed as the apotheosis of Islamic art laying its real nature on two elements, namely ‘wisdom’ and ‘technique’. By the help of the first element, the artist observes mystic and religious truths; through the other, he manifests his inspirations and mental ideas and makes an astonishing change in the real world. Respecting the principles of Shiite religion is one of the main foundations of creating works of art among Islamic artists, and the method of its manifestation has been varied in terms of quality and quantity during Islamic-Iranian art history depending on the ruling governments—be them Shiite or non-Shiite ones. In some historical periods especially Buyid (Āl-e Buye), Timurid, and Safavid dynasties, Shiite elements are outstanding and tangible while in other periods they are either hidden or pale [1]. By taking a look at evolution history of Shiite art, it can be concluded that there has been a regular interaction between structure of political systems ruling Iran and this kind of art. Moreover, Shi’a spirit has been mostly under impression of particular arts like architecture and calligraphy. Since the dawn of Islam in Iran, we are facing a wave of construction of some tombs and buildings in the forms of domes and monuments in addition to mosques in Iranian architecture whose ornaments and architecture are in the utmost beauty and quality indicating direct impression of religious beliefs of their constructors. Soltaniyeh Dome is one such historical monument consisting of an octagonal building to which the bodies of Shiite Imams were supposed to be transferred. Discovering and explaining the sacred principles dominating its design is among the most important means to review the spiritual thoughts and knowledge of architectures of Iran. It is also a great way for confirming the beliefs and cultural thoughts of the governors and artists of that time.This huge monument was constructed in Ilkhani era, ordered by Sultan Mohammad Khodabandeh (Oljaito), and executed by the architect Alishah from 703AH/1303AD to 713AH/1313AD in Zanjan [2]. The main purpose of such monument was constructing a tomb for the sultan, and it is narrated that another purpose was to transfer the dead bodies of the first through third Imams of Shi’as from Iraq to that place. This complex represents two periods of decoration—each with different features. In the first period planned for transferring dead bodies of holy Imams, we face some ornaments with tiling decorated with Kufic handwriting in the center that include geometrical designs, Kufic scripts, and rectangular constructions with turquoise, azure, and blue tiles. The ornaments of second period probably date back to the time when the plan for transferring dead bodies of holy Imams was cancelled, so previous decorations including some other beautiful epigraphs and designs were covered by a plaster coating then [3]. Nonetheless, conversion of Sultan Mohammad Khodabandeh to Islam and Shia in the short interval between 709AH/1309AD to 713AH/1313AD helped the propagation of that across the country and it paved the way for absorbing the art exported by the Mogul rulers from the eastern Asian countries in Iranian-Islamic concept and reforming them based on local traditions and experiences [4]. Architecture and decorations of Soltaniyeh Dome are formed significantly under the influence of attitudes of the ruler of the time and his political and cultural approaches which reflect Islamic vision and Shia tendencies both in terms of framework (main Shabestan, verandas, dome and minarets), and decorations (light, colour, epigraphs, sacred figures and numbers).

1.1. Research Goals and Background

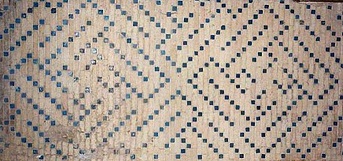

- This research aims at reaching religious foundations of Shia reflected in the architecture and decorations of Soltaniyeh Dome. Moreover, it focuses on identifying the thoughts which provided grounds for the creation of such a huge monument and decorative elements and writings on its surface. The investigations proved that none of the previous researches were in line with the scope of this research, and they were mainly introducing the monument in historical terms and explaining its decorations and architecture in a descriptive way without referring to the prevailing principles of belief. In Soltaniyeh bibliography, names of a large number of books, papers, student theses, research plans, travel accounts, manuscripts and general works on the monument are inserted [5]. Professor Sheila Blair has also significantly contributed to the body of research regarding the art and decorations of this huge monument1 by submitting a number of papers on this topic.A list of some books and papers on the architecture of this building is provided in the following table. Among them, only the paper written by Mr. Hatef Siahkouhian titled ‘The Effects of Islamic Mysticism on Iranian Architecture by an Emphasis on Decorations of Soltaniyeh Dome’ has had a look at mystical and spiritual foundations dominating the epigraphs, figures, and decorations of this significant monument. Some written works in the field of Shiite art are mentioned below references.

|

1.2. Research Questions

- What are the intellectual foundations and principles of Shiite religion? To what extent can the architecture and decorations of Soltaniyeh Dome express the spiritual principles and dominant message of the founders and the spirit manifested in this huge monument? By analyzing the artistic elements of this monument, the present paper indicates how the beliefs and teachings of Shiite religion are inserted in the contents of epigraphs, figures, and the colours in this magnificent construction.

1.3. Research Method

- This research employs a descriptive, analytical, and interpretative methodology, and the data has been collected through field and library studies. First of all, a sufficient explanation on procedure of construction of Soltaniyeh Dome and the goals behind that is provided by referring to the historical and art resources; subsequently, the type of architecture and implemented decorations are studied in a descriptive way. Afterward, by expressing the fundamental beliefs of Shiite religion, the facades of architecture and decorations of Soltaniyeh Dome are explained in an analytical and interpretive way.

2. Performance and the Causes of Creation of Soltaniyeh Dome

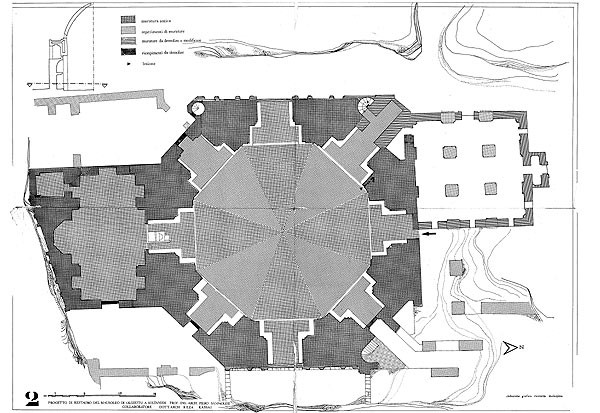

- Form —or the facade of work in Islamic art and architecture— is considered to be a reflected image of meaning. In other words, meaning is the basis for the facade and appearance of the construction in the mind of an artist, and is then shaped into various artistic forms. But it should be considered that appearance of the meaning follows a pre-set cause. Therefore, assuming the fact that architectural aspect and decorative forms of Soltaniyeh Dome are formed on the basis of Shiite thoughts and beliefs, causes and roots which paved the way for flourishing of such meanings and concepts in Ilkhani era need to be clarified beforehand. In last years of his life, Ghazan Khan, the 7th king of Mogul, decided to construct a city in a grassland area later known as ‘Soltaniyeh’. It contained a school, a clinic, a guest’s reception, a house of Sadats (the ascendants of Imam Ali), a convent, a library, a law office, a court, and a grand mosque. The construction began as of 703AH/1303AD by Oljaito (brother of Ghazan Khan) and it took about ten years to be completed [6]. According to the tradition prevalent among the kings of Mogul, a great dome was constructed in the middle of city upon his order to be used as his tomb2. It had lots of endowments and was managed in a unique way (figure 1), although Etemadal-saltaneh denied the matter in the book Meratol Boldan and named it only as a grand mosque in that era3. In any case, at the time of building the construction Sultan Mohammad was a Muslim and he had a tendency towards Hanafite belief of Sunnis. Until he officially became a Shiite in 709AH/1309AD upon encouragement of one of his high-ranked men, Tarmtaz, and he ordered the preachers to mention the names of Ali, Hassan, and Hossain, to inscribe the names of twelve Imams on coins across Iran, and to add the phrase ‘Hurry for the best deed’ in the call for prayer [11]. In the meantime, all the Shiite top clergymen from all regions were invited to come to his court, and from among them, Sultan chose the greatest elite who was Jamaleddin bin Motahar Helli (Allameh Helli) and made him his attendant [12]. According to some historical resources, after changing his religion, Sultan Mohammad decided to turn his grave into a shrine for the bodies of Imam Ali (pbuh) and Imam Hossian (pbuh); though the idea was ruled out by some great scholars of Shia and hence cancelled. The interesting point is that the religion conversion and the order of Sultan for transferring the dead bodies of Shiite Imams took place at the beginning of the first stage of the decorations.4 According to date of some epigraphs made on the walls, external decorations were completed in 710AH/1310AD (façade of eastern veranda) and the internal decorations were completed in 713AH/1313AD [14]. In the beginning, the construction was supervised by Khajeh Saadeddin, the Shiite minister of Sultan Mohammad, and after he was murdered in 711AH/1311AD, Khajeh Rashideddin Fazlollah, a wise minister of shafei belief took his place. Tajuddin AliShah Jilani was the last manager of the construction who, after killing Khajeh Rashideddin Fazlollah and destroying many of his works, undertook the decorations of the second stage. [14]. Therefore, it is necessary to place our interpretations of the decorative elements of this huge monument in line with intellectual and religious circumstances and with the grounds for the emergence of generation of political elites and Shiite scholars in that era.

| Figure 1. Dome of Soltaniyeh |

3. Architecture and Decorations of Soltaniyeh Dome

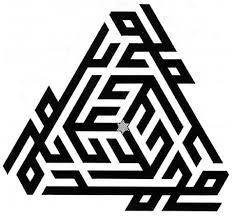

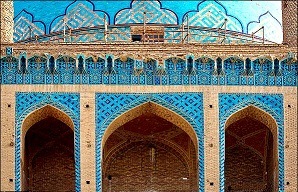

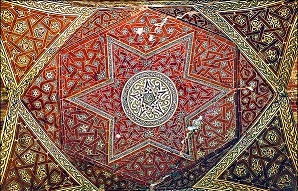

- Iranians have presented the greatest examples of art based on Islamic vision and Soltaniyeh Dome is one of the most outstanding ones. This octagonal monument—with a hemisphere dome as high as 54m and a diameter of 25m—has eight minarets coated with turquoise and azure tiles of Khofte-bidar style which all have added to their beauty and strength. There is a labyrinth below the minarets circling the monument with arched roofs covered by decorative plaster work in imitation of a delicate brick work [15]. The roof of western, northwest, eastern and northeast verandas in that part are decorated with star-shaped motifs with the word Allah in the middle written in Sols script ; by implementing white, cream, and ochre bricks and colorful figures, a masterpiece in combination of colors, plaster, and brick is presented. This labyrinth which is thought of as the roof of the monument and a leg for the dome leads to the second floor through some spiral stairs. The second floor is actually a corridor around the monument and consists of some rooms facing the main part of the building. This part has some beautiful decorations including tiling, plaster work, honeycomb work (Muqarnas), a combination of tiles, bricks, and epigraphs that are “among the newfound types of art of calligraphy in Islamic architecture of Iran.” [16]. The eight sides of monument are presented in the ground floor in the form of eight porticos (four big and four small) representing the eight gates of heaven; their ‘good gates’ include three floors and three parts: the main Hall of Worshiping, Prayer room, and Cellar (Ghonbadkhane, Torbatkhane5, Sardabe) [7]. Sheila Blair describes the internal space of Soltaniyeh dome as follows:“The high internal space of Soltaniyeh monument, which is one of the highest connected spaces in the middle centuries with a magnificent outside outlook of the huge construction, deeply astonishes the viewer. The glory and dignity of its space indicate the capability of the designers who could make Sultan Mohammad`s dreams for such a unique and complicated monument come true” [17].As mentioned before, tiles and bricks with epigraphs, mingled figures of flowers and stars were used to decorate the inside walls of the monument during the two decoration phases. The four main walls of the monument are decorated with a design of intersecting polygons and pentagram stars by using tiles and plaster work, and the other four walls are decorated with blue tiles and light brown bricks. The unique method of implementing the plans and decorations of Soltaniyeh Dome indicates that “the construction of this tomb was not an imitation of any other building and was an invention in construction of a monument with magnificent decorations, proving that tiling reached its climax in Ilkhani era.” [18] There are many structural and written elements in architecture and decorations of this huge monument that have created a unique balance and eminence supporting the achievement of religious and spiritual goals of Shiite belief in that era. Moguls’ religious tolerance of their ideas in Ilkhani era promoted in most cases religious debates and a kind of religious freedom was prevalent across Iran [19]. In the meantime, religious policies of Sultan Mohammad Khodabandeh provided freedom of speech among the Shia which was unique until after Buyid dynasty (Āl-e Buye) in Iran and it created one of the first Shiite architectural works among civilized Iranians by entering into the realm of art and architecture.

4. Religious Basics in Shi'a

- Elements of Shiite art—affecting Iranian-Islamic art or finding a way through which they could express themselves—are a combination of beliefs, myths, and events of Shia’s history. Imamate and believing in Imams` right to guide people after Prophet Mohammad are the most essential and basic beliefs of this religion that play a significant role in religious and social life of the Shia. Believing that Holy Imams are like saviours and can intercede people in the next world are also among other beliefs rooted in Quran, traditions, and life of prophet Mohammad which have been transferred to the masses through jurists and preachers. In the verse 72 of Al-Ahzab sura, Allah says, “Allah wishes only to remove Ar-Rijs (evil deeds and sins, etc.) from you, O members of the family (of the Prophet), and to purify you with a thorough purification.” [49] Moreover, in prophet`s quotes Saghalien and Jaber, the Shia consider Prophet Mohammad and his offspring up to the last Imam being innocent and consider obeying them imperative [20]. Imam Ali (Pbuh), who has been directly appointed by God and introduced to the community of Muslims by the prophet, is an evidence of necessity of accepting right succession of Prophet Mohammad. It indicates another belief of the Shia that is chastity of the prophet household and Imams. Regarding verse 59 of Nesa6 sura, Imam Ali said, “God ordered to obey prophets and those in authority among you, because they are immaculate and pure and never order committing sins.” [21] Upon another Shiite belief, a religious government must establish a true discipline in Islamic society and prepare the grounds for all people to enjoy full freedom, and individual and social equity under the Divine justice [22].

5. Contents of Epigraphs and Status of Imamate in Shi'a

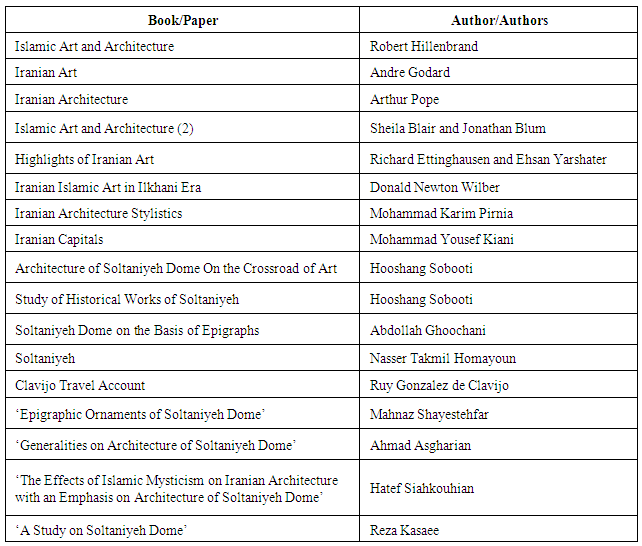

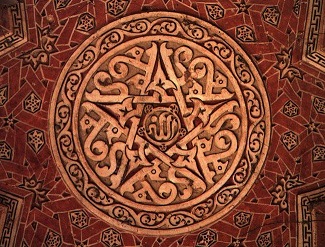

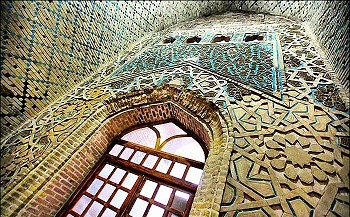

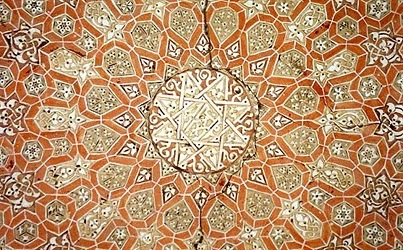

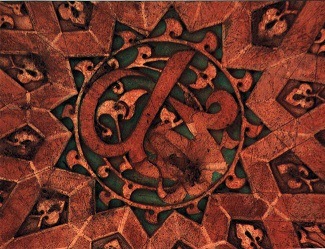

- As semantic and decorative elements in Islamic architecture, epigraphs are significant tools in the hands of governments to develop their religious policies and beliefs among people, and since they are written, they express ideas and thoughts of different periods of time. These epigraphs, In terms of text, are generally divided to three types of construction7, religious, and construction-religious epigraphs, each having a different and special function in architecture. Construction epigraphs are important merely in historical terms indicating issues like name and date of construction and constructor and also mentioning and admiring rulers, and describing historical events. Therefore they have a great value in terms of archaeological discoveries and historical researches. But more value goes to the kind of epigraphs revealing many spiritual facts and mystic debates through their religious themes, the discovery and interpretation of whose meaning lead to recognizing the religious state prevalent in the relevant era [23]. Religious epigraphs of Soltaniyeh Dome are among the solid evidence in identifying this historical monument, religious attitudes of Sultan Mohammad (Oljaito) and policies of the authorities. The epigraphs made in decorations of the first period of this monument are usually written in beautiful Kufic script and in ‘Muaghal’, ‘Mushajjar’, ‘Muwashah’, and ‘Muwaraq’ (leafy) styles consisting of Names and Words of Majesty, names of Prophet Mohammad and Imam Ali, some verses of Quran, and prophetic quotes that were completed in year 713AH/1313AD. The epigraphs of the second period are also written in Sols and different Kufic handwritings such as Mohaghegh, Reihan, and Naskh script and are mostly made of plaster and contain Quranic verses, prophetic quotes and titles of the Prophet and Shiite Imams [24]. Among the most beautiful epigraphs of the first period of this monument, is the one with the script ‘Glory be to Allah’ which, as one of the important slogans in Islam, has been written five times on interior surfaces of eastern porticos combined with bricks and tiles in beautiful handwriting of Muaghali. There is also a pentagram star on the side wall of eastern portico, in combination of bricks and tiles and in a decorative Shamsa8 indicating the divinity of the position of Prophet in Shiite school, whose sides consist of the word ‘Mohammad’ in Bannaei script.On the other side wall of this portico, the word ‘Ali’ can be seen in the same combination and structure inside Shamsa and the star inside it. Blue-like reflection of such Shamsas, which bear the holy names of Ali and Mohammad, represent a shining sun of prophecy and Imamate in the sky of Shiite religion as well as beliefs of constructors and their guiding role.9 (Figures 2 & 3)

| Figure 2. 10-side Shamsa and reflection of name of Mohammad (محمد) |

| Figure 3. 10-side Shamsa and reflection of name of Ali (علی) |

| Figure 4. Pentagram star decorated with names of Allah and Mohammad |

| Figure 5. Repetition of names of Mohammad and Ali, outside view of dome |

| Plan No. 1. Name of Mohammad in sides of triangle and name of Ali in the hexagon |

| Figure 6. Four-time repetition of name of Ali in decorations of first period |

| Figure 7. Repetition of the name ‘Ali’ sixteen times in decorations of the second period |

6. Interpretation of Hidden Geometry of the Monument and the World of Ideas (Alam al-mithal) in Shi'a

- The Soltaniyeh Dome is an octagonal space with its concentration point in the centre. In terms of structure and technique of construction, using eight vertical minarets located in inner carcass of the monument has added to its strength and better architectural relationships in two vertical and horizontal directions, and all pressures resulting from architectural arcs and symbols are tolerated by octagonal reflows [14]. Therefore, the reason for the octagonal shape of the monument is providing more strength for the structure and also for the building to be able to stand on its superficial and small foundation; yet, from another perspective in interpretation terms, another reason for that can be found. This octagonal monument, with such an orderly plan, was constructed under inspiration of eight doors of the Paradise and the purpose of constructing it was to incarnate the paradise in the material and non-spiritual world. Whether the tomb was for the Sultan or was meant to be used as a tomb for Shiite Imams, it seems the architect was intending to show the tomb of these individuals as an allegory for the Paradise on earth as their eternal resting place. The basis for this idea is not just an interpretation, but Quranic verses and historical documents. In Verse 17 of Al-Haaqqa sura, we read, “The angels will stand on all sides of it. And on that day, eight (of them) will carry the throne of your lord above their heads.” [49]. from this point of view, the Paradise described in Quran is an octagon with eight entrances. On the same basis, octagonal forms are not only seen in the formation of architectural spaces and structures, but also in lots of decorative figures of Iranian-Islamic traditional arts [31]. The historical basis of such interpretations can be found in many historical books such as History of Oljaito. In that book, among the events of the year 705AH/1305AD, there is a description of Soltaniyeh monument attributing its octagonal form to eight sides of the Paradise, and placing the tomb of Sultan at the centre of that great and imaginary paradise:“And he—Khaje Tajeddin AliShah Tabrizi—constructed a building which was the best of buildings and cause of astonishment. For instance, he made a paradise like building on the foreground, all ceilings in lobe like form and all walls, doors, and surfaces of apron decorated with gems, gold, shining ruby, and turquoise . . . as well as a unique dome inside opening toward four gates, like eight gates of paradise, full of joys of paradise and covered with colourful carpets and astonishing figures like pretty facades . . . .” [11].Colours used in the monument are good evidence of the symbolic imagination of the Paradise as described in Quran which is executed by cheerful colours like yellow, green, white and red.15 A detailed description on this regard is provided in the discussion on ‘Colours and numbers in Soltaniyeh dome’.The substantial point regarding octagonal and symbolic geometry of this monument is that in Islamic art and architecture, allegory has a deep relationship with believing in the world of ideas, and Shiite Muslims have given more priority to this kind of attitude compared to the Sunni. It seems that believing in another world named ‘Alam al-mithal’ is basically rooted in ‘Platonic Allegory’, and ‘Iranian kingly wisdom’ which has evolved after being constantly taken into consideration by philosophers like Sheikh Eshragh [32]. However, Shia’s belief in the next world is, moreover, rooted in Quranic verses and quotes from the prophet and Imams on the basis of which the Shias practice contemplation and introspection. According to the authors, under the influence of such thoughts together with believing in the Intermediate World and according to the interpretative signs of the Paradise in Quran, the artist of this monument achieves such inner contemplation that he imagines the Paradise and creates it in the material and non-spiritual world. Therefore, in interpretation terms, the sacred geometry of this monument is impressed by Shiite teachings and beliefs of this school in terms of allegory and by the imagination Paradise in the world of ideas (Alam al-mithal).

7. Proportionality of Form and Decorations, and Meaning of Justice in Shi'a

- One of the distinguishable aspects of Shiite thoughts is the special attitude of the Shia toward principle of justice which constitute the material and spiritual foundations of this school in conjunction with affirmation of Divine Unity, Prophecy, Imamate, and Doomsday. According to the Shia, Justice means placing things in their right places16, and can be divided to stages like evolutional justice and legislative justice. Legislative justice discusses observing justice on the part of humans in their different kinds of relationships with each other. Evolutional justice, however, is related to the creation and the rules observed by God in creating beings, including humans [34]. In interpreting the verse 90 of Al-Nahl sura, “Allah enjoins justice (’adl) and benevolence (ihsan)” [49], Imam Ali (Pbuh) holds justice as meaning fairness17, and according to him, fairness is placing things in their right places.18 Material manifestation of the principle of justice on the grounds of Islamic art and architecture is like equilibrium [35] in which things are placed where they belong; no part dominates a whole and no whole dominates a part. In other words, every whole consists of all the parts that comprise it, and every part represents a unique whole. [36]. In the past, many of our architectural works were a confluence for the aforementioned relationships manifesting plurality in unity and unity in plurality which represented mental discipline of an artist whose mentality was formed by believing in the origins of justice and Divine order. From this point of view, the visual equilibrium established between the dome and vertical and octagonal minarets of the monument in the exterior can be considered as a wise trick by an architecture who intended to convey the concept of equilibrium to the viewers in the best form. On the other hand, these minarets are places for callers to call people in every part of the town for prayers equally. Therefore, attention to social justice and informing people equally are clearly observed in its spacing and architecture. Precision in spatial connections inside the dome indicates that all implemented parts and elements are located in their right places; there is also a sort of movement and conceptual symmetry accompanying viewers as they enter and walk across various floors. In support of this view, the vast and round area under the dome was a place to go round and hold mourning rituals (Shabestan or Ghonbadkhane); the cellar was a place to keep and bury dead bodies (Sardabe); and Prayer room (TorbatKhane)—a roofed place above the cellar— was a place to perform religious rituals and pray for the dead bodies (Figure 8). All three floors of the monument are also linked to each other by well-formed steps in the most logical way [14], and it seems that the corridors of the second floor toward the main nave have been designed for women to watch religious rituals and go round the grave.

| Figure 8. Octagonal plan and planned repetition of form elements in Soltaniyeh Dome |

| Figure 9. Observing symmetry principle in interior decorations of the monument |

| Figure 10. Geometrical proportionalities in interior decorations and figures of Soltaniyeh Dome |

8. Colours and Numbers in Soltaniyeh Dome and an Inner Attitude in Shi'a

- Innate attitude and knowledge of the Shia toward issues have always been among the most outstanding characteristics of the Shia during history. Being suppressed and having a strong will to establish justice have constantly been notable among the Shiite communities; these traits have found their way into art to imply beliefs and thoughts. Using symbols and ironies in the wide scope of Islamic art and architecture has been prevalent in Shiite art and culture, and a large body of artworks has indirectly reflected basic thoughts and beliefs of the Shia through symbolic forms. Using colours in architecture as a means of revealing concepts paved the way for symbolic expression of many of the innate concepts and a variety of issues in the Shia belief. Plus, using colours was mostly meant to help recall the truths of things and manifest intellectual stages of Shia school in artworks.Colours and their wide variety in Soltaniyeh monument have succeeded well in creating a spiritual atmosphere. Using vivid and allegorical colours reflects a wise expression of traditional architecture and indicates the exalted truth and manifestations of God; artists—employing such elements—prove the existence of God for the believers, “And what He has multiplied for you in the earth is of various colours; surely, in that there is a sign for a nation who pay attention.”21 [49] All these colours are combined in an exalted equilibrium giving a unique appearance to the body of the monument. According to Andre Godard, “The colours used in Soltaniyeh monument were unprecedented until that time in terms of abundance and density; shades, dots, and tiny and delicate figures in colorations were replaced by strong compounds of colourful masses.” [37] The dome is totally covered with turquoise tiles and there is a wide strip decorated with square Kufic script in its base. The minarets and portico flank are also placed in an appropriate combination of azure, turquoise, and white colours on a Khaki brickwork bed (Figure 11). The roofs of portico are decorated with unique figures in dark red.

| Figure 11. Combination of Khaki and turquoise colours in Soltaniyeh Dome |

| Figure 12. Ochre colour of ceilings and its central, white core |

| Figure 13. Reflection of the number 8 in geometrical and epigraphic decorations of the monument |

| Figure 14. Symbol of number 12 in Shamsa decorated with thename of Mohammad (Pbuh) |

9. Conclusions

- In this paper, the vision and beliefs of Shiite religion were taken into consideration initially; then, their influence on the quality of building Soltaniyeh monument manifested in the form of signs, symbols, and ornaments was identified. The findings are presented as follows:The Shiite religion enjoys a comprehensive and deep vision, and the beliefs of this religion are based on Quranic verses and quotes of Prophet Mohammad. Meanwhile, due to the restrictions on the Shia during history, they usually faced severe limitations in expressing their beliefs, so they had to deliberately turn to symbols and metaphors. In a short period of time in Mogul Lithuanians and Sultan Mohammad Khodabandeh eras in which the Shia got an opportunity to become the official religion, Shiite architects gained the opportunity to advertise their beliefs through art and decorative elements of Soltaniyeh monument and reveal Shiite vision through creating architectural spaces, especially religious and tomb architecture for the first time.In this paper, four of the most notable thoughts of the Shia including Imamate, justice, world of ideas(Alam al-mithal), and intuitive and inner attitude of this school, as well as their reflection in spatial and decorative examples of this monument were taken into consideration. Muaghal epigraphs and inscriptions on outer and inner surfaces of that monument prove tendencies and thoughts of this school by referring to two Shiite testimonies of faith and repeating the sacred names of Allah, Mohammad, and Ali through emphasizing Imamate issue along with two important principles of affirmation of Divine Unity and prophecy. The octagonal space of the monument, Quranic and narrative basis of number 8 on the carriers of the Throne of God, and sublime Paradise are also overt points to the paradise-like incarnation of the monument on earth which can be achieved only through background of Shiite beliefs and believing in the world of ideas. The spatial diagram of this tomb monument shows a regulated and planned movement, and by a regulated equilibrium, it directs viewers’ steps across its three floors to a kind of elevation. This equilibrium and proportionality, which is intensified as you enter the monument and move around in it, can be related to the concept of justice in the Shia.The unique proportionalities implemented in decorations and geometrical figures of the monument also demonstrate highly artistic and architectural achievement in this monument. The inner and intuitive attitude of the Shia can be observed in symbolic expression of the concepts via two essential elements of colours and numbers in geometrical figures and decorations of this monument. Employing blue, green, and azure colours in most parts of the monument indicates tendencies toward spirituality and meaning; moreover, these colours remind viewers of the world of ideas and the memories of Paradise—where they have come down from. Turquoise colour in this monument refers to the absolute colour of the Shia and speaks of genuine and religious identity of the constructors and artists of this tomb monument. The numbers used in the form of elements and star-like figures of this monument represent some concepts like the five members of the Prophet household, the twelve innocent Imams, and name of Ali (Pbuh) in Arabic alphabet having numerical values that are highly respected in Shiite beliefs and thoughts. Generally, contrary to the beliefs of some researchers and historians of Islamic art which consider the annihilation of artworks and rich culture of Iran and the spiritual basics of Islam as the outcomes of the Moguls` invasion of Iran, it should be noted that this negligence was largely compensated for in architectural space of Soltaniyeh Dome, and as one of the first absolute works in Shiite architecture, this rich artwork was formed based on Islamic wise thoughts and culture. In other words, according to the aforementioned interpretations and in line with historical evidence remaining since that era, the architecture of this monument was the outcome of short-term thought of Sultan Mohammad Khodabandeh in converting to Shiite religion and putting the Shiite ministers and elites to work in the Ilkhani government.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The corresponding author would like to thank Prof. Hassan Bolkhari Qahi to guide and let me use his knowledge to accomplish this article.

Notes

- 1. Some of her papers are as follows:Sheila Blair ‘The Epigraphic program of the tomb of Oljaito at Soltaniyeh: Meaning in Mogul Architecture’, in journal of Islamic Art, vol.2 (1987), 43-96.SheilaBlair ‘The Ilkhani Palace’, in Art Orientalis, vol. XXIV (1994), 244- 235.SheilaBlair ‘The Mogul Capital of Soltaniyeh the Imperial’, in Iran, vol. XXIV (1986), 139- 151.SheilaBlair ‘Soltaniyeh Monuments’, in Encyclopedia of Islam, 2end.ed, vol. 8 (1995), 860- 861.2. Eight researchers such as Rashidi in Jameol Tavarikh believe that Sultan Mohammad is buried in the cellar of this monument but twelve other researchers have rejected the idea. [7]. they believe that he was buried somewhere in hidden due to some political reasons or the beliefs of Mogul kings to their ancestral rituals (Shemini). It reads so in Roazatol safa by its author: “Oljaito passed away at the night of Eid e Fetr in 716AH/1316AD, and he was buried under a dome that he had built in Soltaniyeh.” [8]. Mohammad ibn Mahmoud Amoli believes that he was buried there as well: “Oljaito built a dome with eight minarets to be served as his tomb later. He built some charity houses there and donated many properties to the monument.” [9].3. “The idea that the monument was built to be the tomb of Sultan Khodabandeh (Oljaito) is completely wrong and it was a Friday mosque from the very beginning and another monument was build next to that to be served as a tomb for Sultan Khodabandeh that is already there and it called as ‘Chaharsoo’ by the people.” [10].4. Professor Pirosan Paolozzi writes so in this regard: “Oljaito was the first emperor of Moguls periods in Iran who converted to Sunni religion because he was already baptized in his childhood. Due to political and state issues, he converted to Shi‘a later. His tomb underwent the same changes during its construction because it was generally designed to be used as his tomb but it was immediately allocated to a tomb for the dead bodies of Imams and the martyrs of Karbala. By doing so, he was planning to give a lasting name and reputation to Soltaniyeh city but his intention was not only turned down in Baghdad but also across the whole Iran and for that reason he had to change his mind.” [13].5. It was named TurbatKhaneh because according to a narration, Sultan Mohammad ordered to use soil of Karbala (Turbat) in some parts of the monument to give holiness to that and it shows his passion to Shi‘a Imams.6. “Believers obey Allah and obey the messenger and those in authority among you. Should you dispute about anything refer it to Allah and the messenger, if you believe in Allah and the last day. That is better and the best interpretation.” [49]7. In Persian: Ehdasiyeh8. “Shamsa is a star or sun like design and close to circle in decorative arts like tiling, plaster work, carpentry, writing and the like.” [25]9. The basis of our interpretation is God pointing to the role of stars in guiding people in some verses of Qur’an. In verse 97 of Al-Anaam Chapter He says: “it is He who has created for you the stars, so that you can be guided by them in the darkness of land and sea. We have made plain our verses to a nation who knows.” [49]10. Verses 45 and 46 of Al-Ahzab Chapter11. It seems that the power of Shi‘a and its spread and official prevalence in the country reached its climax in that year of ruling of Sultan Mohammad Khodabandeh and it was seen through themes of epigraphs belonging to that decoration era as well issuance of coins with Shi‘a slogans that were mostly made in 710AH/1310AD. On the other hand, a variety of historical books prove the idea. In the book of Religion and State in Iran in Mogul Era, we read: “Once Sultan Mohammad Khodabandeh converted to Shi‘a religion, Sa’adeddin Savoji, who was not a minister yet, was responsible for all the affairs from allowing the Shi‘a clergymen to get involved and develop their goals to issuance of orders to officially recognition of Shi‘a religion across the country and he became a minister one year after the sultan converted to Shi‘a and the works of that sect faced a remarkable progress in that year.” [12]12. Some people believe that this verse of Qur’an protects the requirements of humans and accordingly, it has been selected for the monument and repeated to protect the monument against accidents during times.13. There is an epigraph written in Kufic inside Torbat Khaneh that belongs to the second period of decorations and some traditions of Imam Ali (Pbuh) are quoted there, but the texts are not clear because some parts of plaster works are ruined. [29].14. For more study in this regard, refer to: H. Sobooti, Architecture of Soltaniyeh Dome over Art Passage, 1st edition, Tehran: Pazineh Publisher, 2001, P 98-115.15. For more study in this regard, refer to: H. Bolkahri Ghehi, 2011, “Metaphysic of Color in Islamic Thought and And its impact on Formation of Book of Chivalry on Color”, Research Letter of Visual Arts, No. 2, 5-14.16. In that regard, Imam Ali (Pbuh) says: “Justice puts things in their places […].” For more study refer to: Imam Ali (pbuh), Nahj al-Balaghah, tradition 437.17. “Here 'adl means equidistribution and ihsan means favor.” For more study in this regard, refer to Imam Ali (pbuh), Nahj al-Balaghah,, tradition 231.18. We come across such concept in sentences like “Do justice for Allah and do justice towards the people” in letter No. 53 and “Behave your selves justly with the people” in letter No. 51 of Nahj al-Balaghah.19. The concepts of fate and Divine measurement in creation of beings have been emphasized in various verses of Qur’an: “indeed, Allah brings about whatever he decrees. Allah has set a measure for all things” (65:3), “indeed; we have created all things according to a measure” (54:49), “it was he that made the sun a brightness and the moon a light, and determined it in phases” (10:5). [49] In his Sermon No. 91 Nahj al-Balaghah, Imam Ali (Pbuh) gives such an explanation on God measuring creatures: “What made it stand up with accurate measurements.”20. Refer to: Imam Ali (pbuh), Nahj al-Balaghah, Sermon No. 91.21. Quran, verse 13 of Al-Nahl chapter22. On the advantages of wearing turquoise ring, Imam Ja'far Al-Sadiq (pbuh) says: “The hands of one who is wearing turquoise ring shall not face poverty.” It is said that Imam Ali (Pbuh) was always wearing a turquoise ring with the figure of ‘Allah al- Malek’. Also Prophet Mohammad (Pbuh) has said that: “God says: I am ashamed of turning down the hand extending to me for asking something while wearing a turquoise ring.” [40]23. Quran, verse 100 of Al-Taubah chapter 24. Quran, verse 35 of Al-Noor (the light) chapter25. Quran, verses 1, 2, 3 of al- Fajr chapter.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML