-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Arts

p-ISSN: 2168-4995 e-ISSN: 2168-5002

2016; 6(1): 1-10

doi:10.5923/j.arts.20160601.01

Post-WWII Italian Migration from Veneto (Italy) to Australia and Transnational Houses in Queensland

Laura Faggion, Raffaello Furlan

Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, College of Engineering, Qatar University, Doha, State of Qatar

Correspondence to: Raffaello Furlan, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, College of Engineering, Qatar University, Doha, State of Qatar.

| Email: | drrajnish_raj@yahoo.com |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper explores the phenomenon of post WWII Italian migration (from the Veneto region) to the State of Queensland in Australia. The exploration is linked with the topic of the accommodations where respondents resided since their arrival in Australia. The data was collected in Australia from semi-structured interviews conducted with ten families native to the Veneto region, who migrated to Australia after WWII. All interviews were conducted in the language preferred by participants, which corresponded to their regional dialect and the Italian language interpolated with some Austral-Italian1 words. The interviews have been transcribed and subjected to the first level of analysis - thematic analysis - following orthodox practices (Kitchin & Tate, 2000; Seale, 2004). The analysis of the transcript material generated a number of themes, which, after being subjected to a second level of analysis using phenomenological hermeneutics, have been validated by the respondents. The themes have been ordered into two groups corresponding to first and last (or permanent) dwellings’ migration experiences.

Keywords: Italo-Australian Immigration, Housing, History

Cite this paper: Laura Faggion, Raffaello Furlan, Post-WWII Italian Migration from Veneto (Italy) to Australia and Transnational Houses in Queensland, International Journal of Arts, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20160601.01.

Article Outline

1. Migration Experiences and First Dwellings

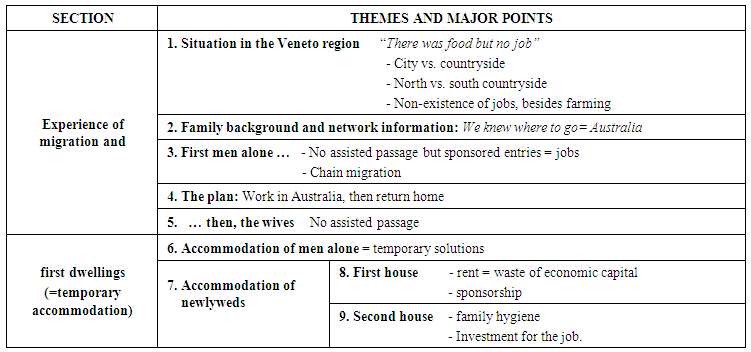

- The discourses about migration experiences lived by migrants from the Veneto region provided insights, which have been structured into nine main themes: (1) the conditions in the native region prior to departure; (2) the influence of respondents’ circumstances on their migration decision; (3/4/5) the manner in which they migrated - firstly men, then followed by wives - and their particular plan; (6) the accommodation where respondents, as single men, resided; and (7/8/9) the accommodations where respondents, as newlywed couples, resided. Figure 1 summarises the themes and the major arguments discussed in this section.

| Figure 1. Experience of Migration and first dwellings: themes and major points |

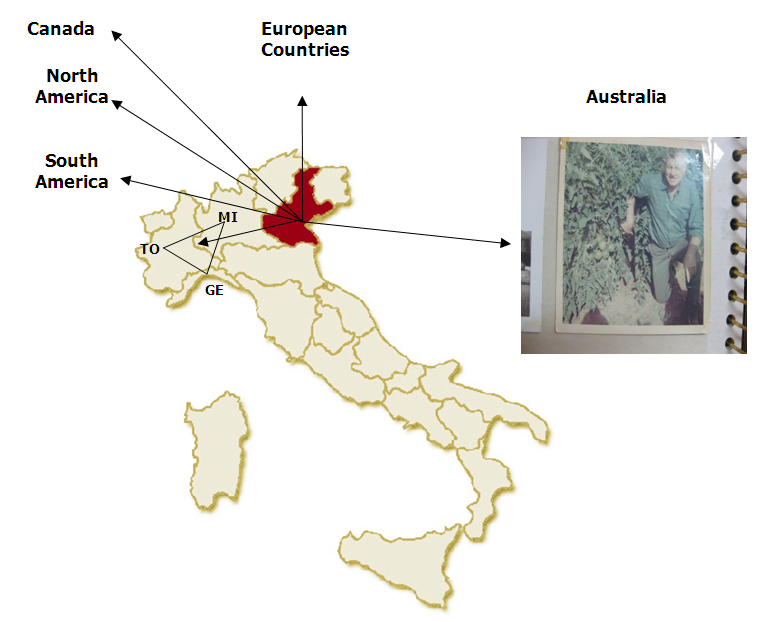

| Figure 2. Map of Italy and the movements of people from the Veneto region |

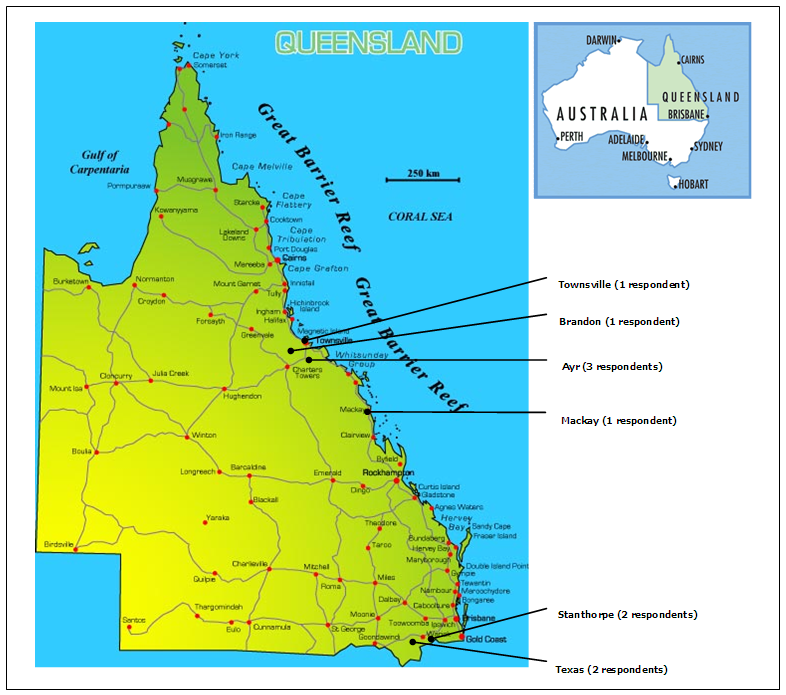

| Figure 3. Map of Queensland showing the localities chosen by the respondents of this study in which to live and work |

| Figure 3. First house of an interviewed couple |

| Figure 4. Kitchen garden in the back yard of Italian migrants’ house |

| Figure 5. Example of house in brick veneer belonging to one migrant family |

2. Experience of Migration that Led to the Last and Current Dwelling

- The following section is concerned with investigating the migration experiences lived by the informants in this study that led to the construction of their current houses in Brisbane. This concerns two important themes: (1) the transformation of the informants from sojourners to settlers; and (2) new investments made by the informants in Australia, which include the construction of their current house in Brisbane.From sojourners to settlers: Australia becoming ‘home’At the beginning of the 1980s, after years of saving, migrants finally faced the crucial moment of repatriation to Italy: a moment that had been postponed for almost three decades. According to Bolognari (1985) very often there is an implicit intention to return to the home country, as in the case of the respondents of this study. Moreover, as mentioned by participants, many of their friends, who also migrated to Australia for working purposes, returned to Italy with their families and savings in this period. However, participants in this study did not return. Why did they decide to stay in Australia and abandon their plan to return to Italy?During the interviews the couples clearly recalled the time before making the decision to return to Italy and adhere to their initial plan, or to settle permanently in Australia and abandon their desire to go home. Respondents reported many sleepless nights were spent pondering on what to do. In most of the cases, the weight of this decision and the emotional tension experienced were evident during the interviews. Four male respondents reported that they went back to Italy to evaluate the situation with a view to return permanently. At the end of this stressful process, after months of discussions and deep thoughts, all of the interviewed families made the decision to remain in Australia. At this point participants were asked what pushed them towards this choice, given their intense desire to return to Italy. The reasons can be summarised in four key points: (1) children (education and work in Australia); (2) breadwinners employment; (3) presence of other family members; and (4) the Australian way of life.The choice to call Australia home was made first and foremost because of their children: for their education and insertion into the world of work. According to the interviewees, for the younger children, ranging in age between 10 and 13, it would have been easy to go back to Italy and to be integrated within the Italian school system, however for the older children (16 to 20), this move would have been far more difficult. The latter had already completed their compulsory education in English and, fearing that they would not have sufficient proficiency in Italian to take university courses in Italy, they opted to remain in Australia. From the point of view of the parents, the risk associated with the choice of the older children was to disunite the family between two countries: younger children and parents in Italy; and older children (at a critical age) in Australia. This is one aspect that affected the decision of the respondents to remain in Australia. The other relates to employment. The interviewed couples compared employment for children in Italy and Australia at the beginning of the 1980s, and considered that the job market was more favourable in Australia. Another reason the migrant couples put forth in various interviews as a justification for their choice of settling in Australia was the employment situation of the breadwinners. A few participants expressed their frustration at the impossibility of moving the family back to Italy because they could not find a job as profitable as the one they had in Australia. Several other respondents revealed the same disappointment, and acknowledged that the well paid positions they held in the host country were a sufficient motivation to remain. At this stage of their lives, in fact, the men had managed to establish their own business enterprises and were self-employed either in their sugar cane plantations and farms or in the construction industry. Other male respondents were employed by Australian construction companies and had gained enough experience in their jobs to reach supervisory and managing positions, thus securing a profitable salary. In both cases, the earnings obtained from such jobs could never have been matched in Italy and this, for them, was a sufficient reason to remain in Australia. A third motive advanced by respondents was the presence of family members who decided to settle permanently in Australia. From participants’ descriptions, it was revealed that the social ties existing in the new country compared to the nuclear family lost in Italy or dispersed throughout the world had significance in motivating the respondents to settle in Australia. Finally, among the reasons that convinced Italian migrants to remain in Australia, was the way of life, judged to be more relaxed compared to life style in Italy. This was, in part, based on the fact that there were far fewer people in Australia spread out over a vast territory. At the beginning of the 1980s (corresponding to the time when the respondents were deciding where to live) Italy’s population was 56 million inhabitants, distributed over a territory slightly bigger than New Zealand (ISTAT, 2011), compared with 15 million of inhabitants in Australia, a territory larger than Europe (ABS, 1996). Today Italy has 60 million people and Australia has 22 million inhabitants. This corresponds to a population density in Italy of over 201 people per square kilometre (ISTAT, 2011) compared to 2.9 people per square kilometre in Australia (ABS, 2011). These figures help to explain why the informants considered life style in Australia to be more relaxed than that in Italy. Therefore, for all the reasons explained in this section, the respondents relinquished the desire to return to their homeland. In this way, the interviewees transformed themselves from would-be returnees or ‘ sojourners’ (Jacobs, 2004) to non-return migrants or settlers. Permanent investments in AustraliaAs a result of the decision to settle permanently in Australia, the interviewed couples embarked on a series of investments with their accumulated funds formerly designated for Italy. These investments took place in the 1980s and early 1990s on the Gold Coast and in Brisbane, as shown on figure 6: an apartment block in Toombul (Toombul is a suburb, 8 km north-east of Brisbane CBD).

| Figure 6. Apartments blocks in Toombul (Brisbane) |

3. Conclusions

- The focus of this paper was to explain the experiences of a limited and specific group of migrants, experiences linked to accommodation in Australia, which led respondents to the construction of their own homes in Australia. The first part of the paper examined the situation in the Veneto region during the post-WWII period and revealed the family background and information network, which contribute to the migration of the respondents to Australia. This was followed by describing how informants migrated and by highlighting their activities in the first years spent in Australia. Their plan was to work in Australia for a short period of time and then return home. The paper illustrated the various types of accommodation available for single men and for newlyweds and explained the reasons why the respondents bought their dwellings in Australia. The second part of the paper explored why informants decided to remain in Australia, which converted them from migrant workers to settlers. This led interviewees to make investments in Australia, which finally led them to construction of their current houses.

4. Discussion: Italian Migration and Dwellings in Queensland

- Reflecting on the experience of migration from Veneto to Australia, it involved an understanding of the nine expounded themes, here reassumed in four key points: (1) the reasons behind their decision to leave the native country; (2) the liminal plan as thought out by the informants in regards to their migrant experience and the ‘adjustments’ shaping it; (3) the initial accommodation in the host country; and (4) the decision to settle permanently in Australia, a decision that led the respondents to construct their final and current accommodation in Brisbane. What follows is a discussion of the above four themes.From the first interviews it emerged that two factors influenced Veneto’s migrants decision to migrate to Australia in the post WWII period: the first was closely related to the economic conditions within the migrant’s home country, while the second was concerned with the family background and the information network of the informants. Firstly, in describing the situation in the Veneto region during the post WWII period, informants made extensive use of words such as ‘miseria’ (extreme poverty, misery) and ‘povertà’ (poverty) and drew attention to the paucity of work in their region. This scarcity and precariousness of work allowed very low circulation of money in Italy, which, in turn, caused a stagnant economic situation (Padovani, 1984). Therefore, for the interviewed Veneto-migrants group, emigration was the only feasible strategy in order to improve their economic standing and to seek relief from the status of financial insecurity.However, there is a second factor that had considerable impact on the decision to leave their hometown and to migrate to Australia. This corresponds with their peculiar background. All respondents had at least one member of the family who had previously migrated to countries such as Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, Canada or Australia. For the interviewed Veneto people, on one hand this denotes that, “migration was an inherited and accepted way of life” as Baldassar argues (2005, p. 25). On the other hand, this long tradition of family migration, or “culture of migration”, as Armstrong (2000) stresses, through the worldwide network of information available to the respondents, guaranteed them up to date news about the state of labour markets and work opportunities, that in turn allowed them a high degree of calculation in their decision making and the mobility to go precisely were these opportunities where available. Australia, in the period after WWII, was perceived by the informants as a wondrous land with ample job opportunities. Thus, in the 1950s, they crossed the ocean to pursue these openings and through chain migration and sponsored entries, they joined uncles and brothers who were already established permanently in rural areas of Queensland. As soon as they disembarked, they started working, first in agricultural enterprises, and later on in the construction industry. By focusing attention not only on the stagnant economic situation in the Veneto region as a push factor, but also on the pull factor of having family already in Australia, this paper highlights the active role of migrants in deciding where and how to migrate. In doing so, this paper reinforces the critique advanced by Baldassar and Pesman (2005) on migration and on the representation of migrants as passive, unfortunate victims at the mercy of economic forces. Significantly, the representation of migrants as passive victims is dismissed here by two other key-factors. First is the liminal plan as thought out by the interviewees regarding their experience in Australia, and second is the modification brought to this plan. The respondents initial plan was that they would stay and work in Australia only for a limited period of time, a maximum of two to three years, after which they would return to their hometowns, where with the earnings gained in the host country, they would marry, buy houses with a piece of agricultural land and start private enterprises to support their families. However, the reality turned out to be very different from what the respondents had planned. In the late 1950s when migrants realised that they needed more time than expected to accumulate their savings, they decided to return to Italy to marry their fiancées and to return with them to Australia, not wanting to live separately and delay the conception of offspring. Sometimes re-emigration to Australia was preceded by a short emigration to other European countries such as Switzerland or Germany, where relatives or friends of the respondents worked. This pattern of returning home and re-emigration to Australia is characteristic of the families analysed in this paper and is confirmed in other studies of migrants from Veneto who came to New South Wales and Victoria (Baldassar & Pesman, 2005). The original plan conceived by respondents, and the modifications they made to it, confer an image of people in command of their lives - not victims.The choices made by the respondents associated with their migration experience had an impact on accommodation in the host country. In fact, as consequence of the preferred migration method of sponsorship rather than the more conventional assisted passage scheme, those migrants were not given government supported housing. On their arrival, the male informants in this study were either hosted by family members already established in Queensland or by using the facilities available to them as seasonal migrant workers, such as shared accommodation in tobacco warehouses or barracks for cane cutters. Then, usually after marriage, they rented in the same areas nearby their relatives, and quite soon purchased their own houses. This initial accommodation excluded boarding houses and migrant hostels, a reality found more in the urban cities. The first houses purchased by migrant families in the 1960s and 1970s were located in rural areas and in small urban contexts in Queensland where male migrants worked. What emerged from the interviews with the respondents to this study is their sentimental detachment from these habitations. In fact, the acquisition of these dwellings occurred when the informants still had the intention of returning to Italy, therefore in the majority of cases the purchases were perceived as a necessity in order to be able to sponsor other family members and friends to come to work in Australia, and as being fruitful investments as renting was seen as being a waste of savings. In addition to that, in a minority of cases, these investments were also perceived as a necessity to provide suitable numbers of bedrooms for growing families or to enlarge the farms of the husbands. Built of wood or brick veneer, these dwellings were inconspicuous, in no way demonstrating the Italianess of their owners. During this time in Queensland then, the most conservative state in Australia (Waters, 2010), diversity was still hidden from the eyes of the dominant culture. This is in contrast with the treatment of the final and current houses the informants constructed in Brisbane.The fourth topic: the decision taken by the Veneto migrants to settle permanently in Australia was taken at the beginning of the 1980s, after attentive consideration, and was influenced by a convergence of various factors including (1) the educational and working future of their English-speaking children; (2) the presence in Australia of other family members; (3) the achievement of good employment or success in their own business enterprises of the breadwinners; and (4) the quieter, more relaxed way of life in Australia due to the presence of less human capital compared to Italy. For these reasons, the original plan of the respondents to return to Italy and establish themselves in their hometowns was purposely relinquished and substituted with the idea of settling permanently in Australia. As a result of this choice, migrants decided to invest their accumulated capital destined for Italy into their adoptive country in medium and large real estate. What is significant for this research study is that these investments included the construction, in the 1980s and 1990s, of their last and current accommodations in Brisbane: accommodations which was supposed to be built in their Italian hometowns.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments, contributing to the improvement of this paper, which is derived from the authors’ PhD thesis.

Note

- 1. Austral-Italian is a linguistic hybrid developed by Italian migrants in Australia (Leoni, 1995). Although one can find examples of Austral-Italian in print, it was born, developed and was established as a predominately spoken language, a language dictated by necessity and as a consequence of mainly oral communications (Leoni, p xix). Examples are: ‘carro’ (from car), ‘tichetta’ (from ticket), ‘farma’ (from farm), ‘tracco’ (from track) (Leoni, 1995).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML