-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Arts

p-ISSN: 2168-4995 e-ISSN: 2168-5002

2015; 5(2): 33-39

doi:10.5923/j.arts.20150502.01

Aesthetic Judgment Style: Conceptualization and Scale Development

Hadi Bahrami-Ehsan1, Shahin Mohammadi-Zarghan2, Mohammad Atari1

1Department of Psychology, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Art History, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Mohammad Atari, Department of Psychology, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Individuals express their opinions toward artworks differently. Hereby, four major styles of aesthetic judgment are conceptualized. These styles consist of concrete, analytical, symbolist, and emotional. Initially, an item pool of 94 items was generated to cover all aspects of aesthetic judgment styles. The current study aimed to develop and provide initial validation for Aesthetic Judgment Style Scale (AJSS). A sample of 260 participants was recruited using snowball sampling method. A package consisting of demographic questions, initial item pool, three subscales of Sternberg’s Thinking Styles Inventory (TSI) and cognitive style scale (CSS) was administered on participants. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using principal components factoring and Varimax rotation and Parallel Analysis (PA) suggested a four-factor solution on psychometrically selected 32 items. Extracted factors were labeled as concrete, analytical, symbolist, and emotional aesthetic judgment styles. Cronbach’s alphas of subscales were 0.71, 0.70, 0.76, and 0.81 respectively. Each subscale was significantly correlated with the related concurrent instrument (P<0.05). Findings of the study supported the psychometric properties of Aesthetic Judgment Style Scale (AJSS).

Keywords: Psychology of aesthetics, Aesthetic judgment, Scale development, Psychometrics

Cite this paper: Hadi Bahrami-Ehsan, Shahin Mohammadi-Zarghan, Mohammad Atari, Aesthetic Judgment Style: Conceptualization and Scale Development, International Journal of Arts, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 33-39. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20150502.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- People are generally fascinated by art and enjoy being exposed to it in many forms. This attraction has caused many tourists to travel long distances to visit a piece of artwork or a museum. Yet, people have different styles of expressing their feelings, emotions, opinions, and judgments toward a single piece of artwork. Research suggests that aesthetic judgments usually involve cognitive, emotional, and behavioral facets [1]. In particular, various affective and cognitive processes play a crucial role in the perception, evaluation, and appraisal of art.Historically, theoretical and empirical research on aesthetic judgment in psychology began in the 1930s with Birkhoff’s aesthetic formula [2], which defined the amount of received pleasure from an artistic stimulus as a ratio of amounts of order and complexity. Other works included Eysenck’s general factor theory [3] and Leder’s multi-factorial model of aesthetic judgments [4].Balance, the extent to which the elements of a pictorial configuration are organized so that they appear anchored and stable [5], is a crucial aspect in the creation and judgment of visual displays [5-7]. Early research on aesthetic preferences of visual objects [3] introduced two principal factors that explained individual differences in aesthetic judgments. While the first determinant of preference judgments refers to what Eysenck [8] described as ‘‘good taste’’ (the ‘‘T’’ factor), the second determinant refers to the preference for complexity (the ‘‘K’’ factor). The empirical bases of the ‘‘T’’ factor suggested that people tended to agree on liking visual aesthetic objects [3], and that the judges who agreed the most with the average judgments were the same individuals among different types of stimuli [9]. This dispositional ‘‘T’’ factor, aesthetic sensitivity, was identified as the ability to identify differences in terms of harmony and good design [10], and more generally, as the extent to which his judgments relate to the external standard of value which is being employed [11]. On the other hand, in Leder’s [4] model, aesthetic sensitivity refers to the ability to perform a set of basic perceptual analyses of the stimulus, based on the stimulus’ balance-related features, such as order and symmetry. A recent study has reported that aesthetic sensitivity has different sources of variation and is correlated with intelligence, openness to aesthetics, and divergent thinking [12]. Moreover, in the past few decades, a growing body of research has started to investigate how people respond to art. Different types of personality have been reported to be associated with artistic qualities. Moreover, neural structures of art appreciation have been well studied [13-17]. A successful interpretation of the artwork will evoke a positive aesthetic judgment, while an unsuccessful interpretation will cause a more negative and poor aesthetic judgment. The idea of an association between successful cognitive operations concerning a particular artwork and a positive attitude toward it has also been proposed by Reber, Schwarz, and Winkielman [18]. In their concept of processing fluency they proclaimed that artworks are rated more beautiful the easier they are cognitively processed. Parallel to the sequence of cognitive processes, there is a continuous stream of an affective evaluation of the artwork. People have different styles of evaluating an artwork. Some people tend to analyze different artistic qualities of the work while some others tend to associate the work with their own personal life. From the viewpoint of Housen [19], the quality of one’s aesthetic judgment changes as the person grows older and masters higher-order cognitive abilities. This developmental point of view has been studied in several studies and the chain of aesthetic stages has been confirmed [20]. Through interviews with five specialists in the field and considering the body of literature, four major aesthetic judgment styles are conceptualized in this study. It was hypothesized that the quality of aesthetic judgment of one would fall into one of the following styles. These four major aesthetic judgment styles were labeled as concrete, analytical, symbolist, and emotional. This taxonomy of aesthetic judgments is consistent with Housen’s developmental theory. Conceptual definitions of the styles are present in this section. Furthermore, a study was designed to develop and initially validate Aesthetic Judgment Style Scale (AJSS) in order for operational definition. Concrete aesthetic judgment style includes judgments which describe artworks by their apparent and superficial qualities. In this style of judgment, one does not display deeper interpretations of the work. Analytical aesthetic judgment style involves making inferences considering artistic guidelines. People with this style of aesthetic judgment make an effort to analyze the artwork and make logical statements about it. Symbolist aesthetic judgment style consists of making judgmental comments apart from concrete or practical ones. References in this style are not directly related to specific instances. Moreover, judgments do not have narrative content or pictorial representations. Emotional aesthetic judgment style forms when affective and emotional statements are greatly used in an aesthetic judgment. One has an emotional bond with the artwork and considers it very close. This judgment style may be considered as an advanced style which is more frequently seen in experienced artists or art critics. It is acknowledged that an aesthetic experience is not solely limited to the arts that were utilized in this study (mostly visual arts), but is in fact a quite common phenomenon in many fields [21-24]. It should be noted, however, that the focus of this scale’s items is limited to arts in the form of paintings, music, dancing, literature, and architecture. There are also several general questions in the questionnaire. A primary item pool of 150 items was generated by authors and three independent art experts according to the aforementioned conceptualization. After checking the item pool for content and literal fluency, a battery of 94 items was prepared in order to be administered.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- A total of 260 students of five major universities and two artistic institutes were selected by snowball sampling method. The average age was M=28.2 years (SD= 7.1 years, range=15–69 years). Data were gathered individually. Questionnaires with more than 20 percent of missing values were excluded from the study.

2.2. Measures

- All participants completed a package of questionnaires including a developed demographic questionnaire, initial item pool, two subscales of cognitive style inventory, and three subscales of Thinking Style Inventory.

2.2.1. Demographics

- The following demographic questions were asked: age, gender, major, educational level, marital status, socio-economic status.

2.2.2. Aesthetic Judgment Style Scale

- The final battery of items was administered. The response option was provided in a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “completely agree” to “completely disagree”. The items were judgmental declarative sentences about various arts.

2.2.3. Thinking Style Inventory

- Three subscales of Sternberg’s Thinking Style [25] were used. Thinking styles are not abilities; however, they are preferred approaches of one to use his/her abilities [26]. Reliability coefficients of these subscales were reported between 0.56 and 0.88 [27].

2.2.4. Cognitive Style Inventory

- Two subscales of cognitive style inventory (concrete and abstract) were utilized. Reliability and validity of the instrument have been reported satisfactory. Cronbach’s alphas of the subscales have been reported between 0.89 and 0.93 [28].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- Data entry and analysis were performed in a blinded manner by personnel who were not involved in the process of data collection. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed. The number of factors to be extracted was determined by factor Eigenvalues above 1.0 (EGV1 criterion) and based on the scree-plot criterion [29]. However, these techniques can lead to factor over-retention [30], so Parallel Analysis (PA) was also conducted. This technique generates Eigenvalues from random datasets that match the actual dataset in terms of the number of participants and variables, and is considered a more accurate technique for determining the number of factors to retain from EFA [31]. Moreover, comparative tests and correlational analyses were carried out. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 21.0) software.

3. Results

3.1. Item Analysis

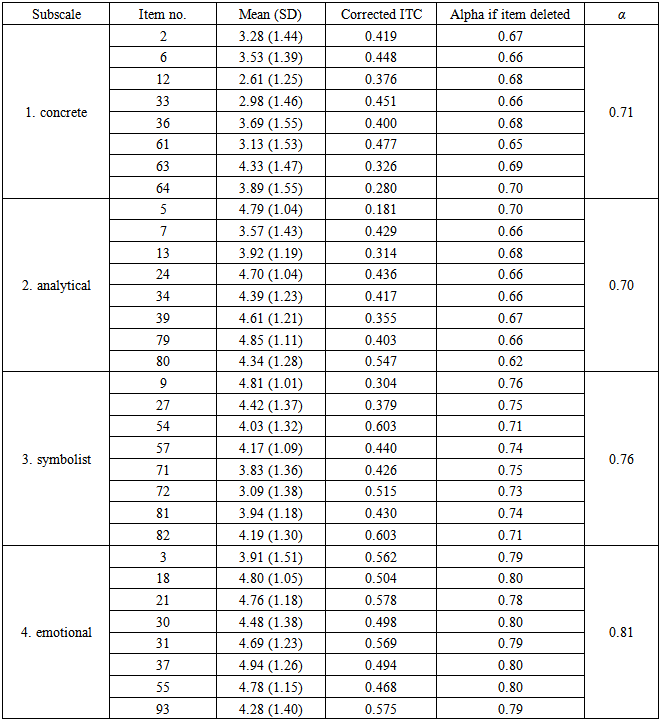

- A comprehensive item analysis was used in order to exclude inappropriate items. For each item, the following indices were checked: Mean (M), Standard Deviation (SD), skewness, kurtosis, squared multiple correlations, Item-Total Correlation (ITC), Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted. For excellence of the scale, 7 items were discarded in this step. Eighty-six remaining items satisfied a set of criteria for item analysis.

3.2. Factor Structure

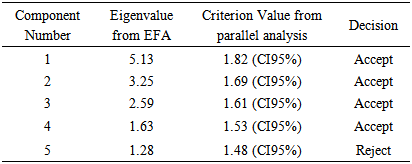

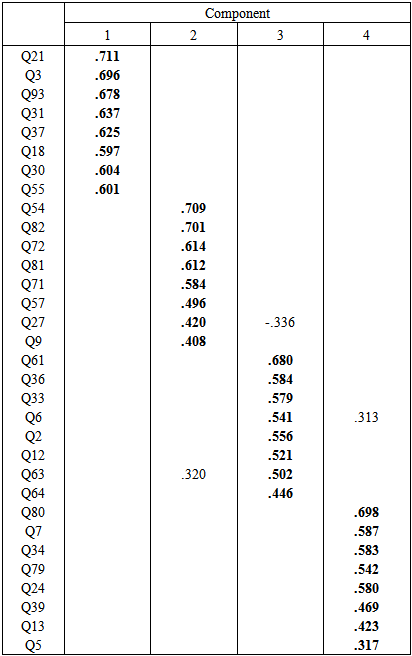

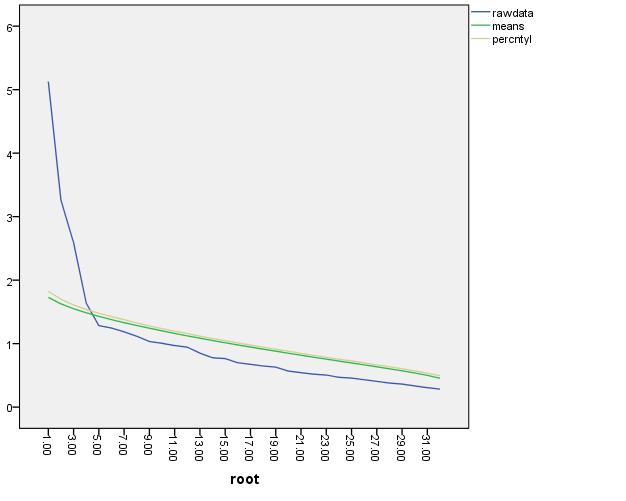

- First, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed and cross-loading items were considered for discarding. Thirty-two items showed the best psychometric qualities in both item analysis and EFA. Different properties of these 32 items are presented in Table 1. Therefore, another EFA was carried out on 32 remaining items. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin’s measure of sampling adequacy was very good (KMO=0.786) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (chi square=2193, P<0.001) indicating that the data was factorable [32]. Then, a principal components factor analysis using Varimax rotation was selected to be performed on the remaining items’ responses from the entire sample. Parallel analysis was performed in this step and four factors had significant Eigenvalues according to PA. Eigenvalues and results of parallel analysis are summarized in Table 2. Scree plot and PA criteria are illustrated in Figure 1. The rotated factor matrix of the 32-item scale is presented in Table 3. Loadings under 0.3 were omitted.

|

|

|

| Figure 1. The scree plot and parallel analysis criteria for accepting factors |

3.3. Concurrent Validity

- Different styles of aesthetic judgment were predicted to be correlated with cognitive and thinking styles. Concrete aesthetic judgment style was predicted to be positively correlated with concrete sequential cognitive style and executive thinking style. Symbolist aesthetic judgment style was predicted to be correlated with abstract sequential cognitive style. Analytical aesthetic judgment style was predicted to be associated with judicial thinking style. Finally, emotional aesthetic style was hypothesized to be associated with abstract cognitive style. Pearson correlation coefficients are presented in Table 4.

| Table 4. Correlation coefficients between AJSS subscales and concurrent instruments |

3.4. Reliability

- Internal consistency was examined for the 32-item scale. Cronbach’s alphas for subscales were satisfactory and ranged between 0.70 and 0.81. Deletion of each item would have led to decrease in internal consistency of the subscale. Items’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

4. Discussion

- This study aimed to conceptualize four major aesthetic judgment styles and develop a psychometrically robust scale for their measurement. Altogether, 94 items entered the analysis. Exploratory factor analysis and parallel analysis suggested a four-factor solution for 32 items with best qualities. The compilation of the AJSS was performed on psychometric and conceptual grounds. An item analysis was done to ensure the primary psychometric qualities of each item. Eventually, a final set of 32 items were retained which had four subscales. Factors were named concrete, analytical, symbolist, and emotional judgment styles.The first factor, concrete judgment style, assesses the extent to which one judges artistic works by their concrete qualities. The second factor, analytical judgment style, describes how much the viewer is eager to analyze the artwork and its different qualities. The third subscale of the test, symbolist judgment style, measures the abstract judgment of one based on symbols and abstract concepts. Finally, emotional judgment style appears to be found in experienced artists who treat artworks as their family members and are sometimes poetic about them. Each factor has eight items. Findings of this study were consistent with Housen’s developmental explanation about aesthetic abilities of one. Moreover, it is also in line with a model of cognitive developmental analysis in aesthetics as proposed by Parsons [33]. Therefore this psychometric scale may be used in research and educational settings as it can reflect students’ styles of aesthetic judgment. Psychometric properties of the scale were reported satisfactory. Content validity of the test was checked and confirmed. The underlying structure of the test was analyzed by EFA and had expected results based upon the primary conceptualization. The concurrent validity of the scale was evaluated as the subscales were associated with expected constructs. Concrete cognitive style, abstract cognitive style, legislative thinking style, executive thinking style, and judicial thinking style were utilized constructs for assessment of concurrent validity. Moreover, the reliability of the subscales fell within acceptable range. Some limitations of the present study are worth mentioning here. First, the sample size could have been larger. Secondly, confirming the underlying structure of the scale by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was not performed in this study. Yet, more research is required to investigate the psychometric properties of the scale via confirmatory techniques.

5. Conclusions

- In sum, AJSS is a psychometrically sound scale in order to assess four major aesthetic judgment styles. It may be beneficial for investigations in research and different aesthetic settings. It is strongly recommended to investigate AJSS’s psychometric properties among different age levels as it aimed to reflect developmental differences as well as styles in evaluating an artwork.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Authors would like to thank Hediyeh Khojasteh (freelance art management professional) for her help in data collection process.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML