-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Arts

p-ISSN: 2168-4995 e-ISSN: 2168-5002

2015; 5(1): 21-31

doi:10.5923/j.arts.20150501.03

Costume and Body Adornment in Dance: A Case Study of Abame Festival in Igbide: Isoko Local Government Area of Delta State, Nigeria

Oghale Okpu

Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Oghale Okpu, Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper attempts to discuss costume and body adornment in dance as it relates to Abame festival of Igbide, Isoko South Local Government Area of Delta State, Nigeria. The type of costume and body adornment determines the style and body movement of dance. A lot of people, even within Delta State do not have the knowledge of this cultural entertainment which is spectacular to those who have witnessed the celebration. It is an attempt to bring into limelight this artistic and cultural development of the culture area to the outside world. It is a socio-cultural activity that brings all the sons, daughters, relatives, friends and well-wishers of the participants to the Igbide town. Some participants come from abroad to make sure that they are involved in the dance. As participation qualifies the individual to become a man, who can be elected into any administrative position in the community and also can rise to any height socially, politically, religiously and so on. Then such a man can also be buried when he dies as a responsible, respective and honourable person within the community. Without this age-grade dance, you are regarded as inconsequential human being and relegated to the background in any socio-cultural occasion.

Keywords: Costume, Body Adornment, Dance, Culture, Abame festival

Cite this paper: Oghale Okpu, Costume and Body Adornment in Dance: A Case Study of Abame Festival in Igbide: Isoko Local Government Area of Delta State, Nigeria, International Journal of Arts, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 21-31. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20150501.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Costume could be regarded as a style of dress or clothes in the style of a period in the past. It serves to adorn the wearer, adding both material lustre and a sense of well-being. The researcher has observed in many dances that costumes are known to have mystical influence on the beholder such that personal power, dignity and wealth are externally manifested. This therefore may be equivalent to the conscious image that man creates in his appearance. Encyclopaedia Britannica (2012) [1] also defines costume as clothing designed to allow dancers or the wearer freedom of movement while at the same time enhancing the visual effect of dance movements. It is also noted by Schumn et al (2012:1) [2] that most costume in films, and drama are carefully elaborated to give information about a certain role character as in case of a king or even a lead dancer of a group. Most costumes are produced traditionally in connection with religious rituals, marriages, chieftaincy titles, social groups as well as to show social status like in the Abame festival. The aesthetic appeal of the wearer is displayed in the creative ideology of the costume and the communicative information sent out to the audience or onlookers. Hence, when Efimova and Kortunov (2013:1669) [3] discussed the Russian National costume, they proved that the costume contributes to the formation of aesthetic taste of the person who wears it and also a symbol of beauty and harmony. Efimova and Kortunor also believe that costume as a work of art has always reflected a certain stage in the development of peoples’ culture, which is closely connected with architecture, painting, music and theatre. This means that costume was associated with customs, and habits that determine the character of the era. The expressive and artistic designed costume also helps to reveal the inner wealth and the dignity of the individual in most African festivals and dances in which Abame is a part.The free encyclopedia (2011) [4] states that dance is a type of art that generally involves movement of the body, usually rhythmic and to music, performed in many different cultures and used a form of expression, social interaction and exercise or presented in a spiritual or performance setting. One can also state that dance is a form of a nonverbal communicative system that is practice by humans and at times performed by other animals (Mating Dance or Bee Dance). Ibagere (2010:49-50) [5] also states that Dance in Africa is functional and in the traditional context, dance is hardly done for its own sake, that is without a social function; and that there is usually an element of communication in African dance. That is why meanings are attributed to dances whenever they are performed. It should be noted that the basic material or medium of dance is the human body and it is “the regularity of the movement coupled with the design of the movement (use of space) that combine to give it meaning” (Ibagere 1994:89) [6]. Ibagere went further to state that lack of proper understanding of the culture may lead to aberrant interpretation of the dance. That means a wrong meaning may be assigned to the dance to wrong response to the people and their culture. It is necessary to say that only those who are conversant with the ideological concept of the dance can actually decode the style of dance and their movements. However, the individual should note that a particular dance displayed in any traditional festival has its own peculiar costume, body adornment, as it relates to the socio-cultural functions in the immediate environment, as could be perceived in the Abame dance. Most costumes are accompanied or embellished with body adornment in relation to the type or style of dance.According to Bacchiocchi (1995:7) [7] the subject of dress and adornment is sensitive because it touches what some people treasure most, namely, their pride and vanity. What we wear is very much a part of who we are. However, Noyster (2014) [8] states that an adornment is generally an accessory or ornament worn to enhance the beauty or status of the wearer; and that they are often worn to embellish, enhance or distinguish the wearer. These embellishments are often used to define cultural, social or religious status within a specific community. Ibagere (2010:35) agrees that body adornment relates to all forms of apparel worn by a person as a member of the society. This includes other properties such as walking stick, head gear, cap, beads, shoes, bangles and other jewelry that help to define or identify the person. He further states that in Nigeria, a multicultural nation generally, accepted that the manner of a person’s dressing reveals the area of origin of that particular person. From all indications, body adornment especially for festivals or dances are usually colourful and are worn to attract attention from audience, visitors, tourists, and other participates in the arena or immediate environment where the festival is being held.All over Africa, body adornment are used for various functions in individual cultural settings and these adornments can be permanent or temporary depending on the festival or dance. However, costumes and body adornments are generally used in most traditional dances to specifically highlight the following;i. Some particular costumes are used to instill fear and threaten the onlooker, especially when such a dancer wears a red and black costume and with the use of black, red and white body decorations around the eye balls, part of the face or chest areas.ii. Costume and body adornment could be used to define a specific lead dancer or character or group of persons within the group.iii. Costume is also used in dance to enhance or emphasise the anatomical structure of male/female dancers.iv. Costume and body adornment are used on some dancers just for the aesthetic appeal.v. Costume and body adornment are used in some cases to distinguish social status, religious inclination, war, ritual and mere entertainment.vi. Costume and body adornment in dance, embellish the flow in rhythm and make the dance more interesting to appreciate by the audience.vii. To some extent, the use of costume determines the level of outstanding the techniques and styles involved in the dance by the dancers. After all, it is the type of dance that determines the type of costume that is relevant.viii. Costume and body adornment in dance, communicate to the audience the cultural environment in which such a dance is practicable.ix. Costume and body adornment in dance also educate the audience on the type of indigenous materials in the immediate cultural environment that can be used to enhance the dance, instead of craving for western materials, therefore it helps in improvisation in some aspects.Costume and body adornment in dance vary tremendously because of the different costumes and religious beliefs of the different societies as well as the purpose of the dance.

2. Relevance of Costume in Performance

- Fine art is referred to as an artistic expression created for its sense of beauty and decoration, such as painting, carving, decorative ceramic objects, sculpture pieces and so on. Applied art is also in the visual arts family but mainly produced for a purpose or function such as graphic arts, textile designs, ceramics and photography. Performing art, is that form of artistic expression for entertainment. They include music, dance, drama and so on. The arts; fine, applied and performing expressions of a people constitute part of their cultural heritage. Mgbada (1978:24) [9] states that culture is a body of human activities showing a distinctive way of life of group of people. Nwosu and Kalu (1978:5) [10] acknowledges this fact but further state that it is rather man-made than God given. According to Wangboje (1989:11) [11] if the culture of the people and their way of life can be seen in their works of art, definitely the costume of the people is an extract of the cultural environment in which it is made.According to Sieber (1972:19) [12] a tight fitting costume or little clothing tends to result in actions and in dance movements that retain the energy of gesture with the torso. While loose clothing which requires continuous adjustment results in characteristic gestures of arms and hands add to the tendency of throwing the body weight into different gestures. Therefore the use of some specific costumes reflect styles and movement of the wearer in performances. Sieber also observes that many African costumes would be considered incomplete without the inclusion of some devices such as whisk, weapon, or fan as an insignia or rank or prestige as seen in most dances. And that prestige may declare itself by a conspicuous, visible and audible accumulation of ornamentation in most costume and body adornment of our traditional festivals. Nwanze (2000:106) [13] believes that the richness of the art suggests a system with a certain degree of social stratification.Bell-Gam (2000:15) [14] also proclaims that costume and hand properties play vital roles in theatre productions. He goes further to state that they do not only explain the characters, social status, age and moral dispositions of the actors but also reveal the cultural background in which the drama is situated. Bell-Gam illustrates the uses and significance of costumes and other artistic objects by actors during performances in the richness of regalia of the actors in different Nigerian plays. Example could be seen in royal regalia in Ola Rotimi’s “The gods are not to blame” where popular adire materials were used to design the costumes of King Odewale in order to reflect the Yoruba culture, and Zulu Sofola’s :Wedlock of the gods” with the use of local materials for costuming. This will also educate the audience about the indigenous materials used and thereby encouraging people to deviate from western materials and work more on improvisation.Obuh (2000:76-77) [15] states that a lot of improvisation is done in the creation of different themes and titles of drama and dances, whether it is tragic, pastoral and comic which makes it more appealing to the different audience. Hence some major figures that play serious roles are masked, while the rest appear in ordinary costume. The mask and costume invariably convey specific identities to the audience. Obuh believes that the most talented actors or “comedian” easily improvised in their performances for special sensitive reactions from the audience.Nevertheless Olaosebikan (1982:59) [16] asserts that what is modest and beautiful in one culture and civilization might be regarded as hilariously funny or even considered insane of outrageous in others. But the determinants of the variations are the customs and social values of such cultural groups. However, Egonwa (1994:8) [17] categorically states that the appreciation and the aesthetic expressions of African art can only be enjoyed and discussed by those who know their cultural values. “These are the style the way an art looks, the iconography - its subject matter and symbolism, and its historical context – the political, social, economic, scientific, and intellectual background that influences the purely art historical events”. Egonwa goes further to state that early western writers following European expectancy patterns have misunderstood our art because of the error of attempting to interpret art forms using their own standards. Therefore the cultural values that give significance to art in Africa and Nigeria in particular are different from those which informed European arts. And as such social functionality has been an important factor in the validity of most African art. These may be expressed in fine, applied or performing art which may also differ according to their cultural acceptability. Most of these submissions are in the concept and context of Abame festival as this write-up will show in the costume and body adornment in the dance proper.

3. The Igbide People

- Igbide is one of the nine administrative clans in Isoko South Local Government Area in Delta State. There is a major water outlet known as Urie-Igbide (Igbide lake) which is connected by a narrow but a deep creek to Patani, an Ijaw town on the River Niger. It was a major route for traders and travellers, until the opening of the highway from Warri to Patani. Therefore, fishing is an all season occupation because of the annual floods and the numerous fishing ponds in both the swampy forest and Urie-Igbide.Igbide town is surrounded by different neighbouring towns. Towards the South is Umeh, Olomor to the North, Emede to the North-East, Uzere to the East and Enhwe to the West. All these towns speak a dialect of Isoko language with slight variations from one town to another.The oral tradition has it that the founder of Igbide town, Eru, came from a town in Imo State called Mgbidi and migrated from there through Elele in Rivers State and through the Niger to Eastern Isoko. He settled first in the present site of Owodokpokpo but because of constant raiding of his home by some warriors and notorious slave dealers from Aboh and Ijaw, he moved into the hinterland and some few kilometers away from the shores of the lake to the present site at Igbide. He made a brief stop over before reaching Igbide at a spot called Otowodo, relatively high environment which is above high flood levels, and left his war materials there. Today, the place is referred to as Egbo-Igbide where past generations had kept their war materials and made shrines devoted to their ancestors. According to Abiagbe (1978:4) [18] and Ikime (1972:1) [19] Eheri, the eldest son of Eru, an explorer and a hunter, left the father’s abode to find his own settlement, presently known as Emede. Nevertheless, the people of Emede claim that they are descendants of the Edo people (Benin) and they have no relationship with the people of Igbide except through intermarriages.The rightful descendants of Eru in Igbide are people from Ekpo and Okporho Kindreds. They are believed to have come from Igbo land through the rivers and creeks. These two Kindreds form a broad division of Igbide known as Unuame, meaning from “the riverine area”. There is another distinctive group of immigrants in Igbide who claim to have come from Benin, through a land route. They are the uruwhre and Owama Kindreds. They are commonly called Okpara – meaning “the land”. Igbide is therefore an admixture of cultures, which has resulted in a sharp division of activities in the land, which is manifested in the Abame wrestling dance.It is a well known fact that Nigerians, like other Africans, are deeply religious as they believe in the existence of God or any Supreme Being. Elaho (1976:6) [20] believes that “communication with God is effected through various gods, goddesses, and ancestral spirits. And these supernatural beings are symbolically represented in concrete forms, where art comes into function. These are usually found in shrines adorned with carved or moulded statuettes and masks, each representing an ideology relating to a specific god and goddess from the worship of which the Igbide people are not exempted.The typical traditional Igbide man believes in his gods and ancestors. The most famous ones that attract a large number of worshippers are Amededho, Edho-Idodo, Oni-urie, Edho-Oboko and Edhivi. Each of these gods has a chief priest, who acts as a mediator between man and the god. These divinities are believed to govern all activities in human endeavours, god of war and peace, god of harvest and fertility, god of wealth, healing and protection. But with the introduction of Christianity, many of the gods and shrines were destroyed especially as most of their art pieces were made of perishable materials like clay, mud and wood. All Christians were now forbidden to take any active part in ancestral worshipping.This is also extended to non-participation in other traditional and annual festivals celebrated in honour of ancestors as well as divinities. At present the Jehovah witness group does not participate in Abame dance. Nevertheless the necessity to preserve this traditional dance is paramount, considering its socio-cultural, moral and disciplinary roles in the community.

| Plate 1. Ovie (king) demonstrating various dance styles with the wife behind showering praises on him in one of their festivals |

4. Abame Festival: Its Origin

- Abame festival is not held in honour of any deity in Igbide. It is a unique and special festival to every indigene. Abame is prominent in the socio-cultural history of the Igbide people. As people in the riverine area, most of their social and cultural activities have been influenced by their peculiar environment.History has it that Abame started from the bailing of ponds. In ancient times when Igbide was quite small in size and population, the community dug some fish ponds together and was under the supervision of the council of elders (Ogbedio). Numerous ponds were dug such as Atawa, Ofori, Oyoze, Uyude etc. On the order of the Ogbedio, the ponds are bailed every two or three years. These ponds were so important to the community that everybody was restrained from fishing in them until the Ogbedio permits.At the bailing time, some people are expected to stay at the Eyo – (starting point) and others go deep down into ovivi (deeper part). The ovivie is only seen when the water has been drained off the Eyo. At this point, struggle for seniority came up and it was difficult to detect seniority among the youths. The only solution to it was to make them wrestle, and the lazy ones or the losers were made to bail while the winners were made to do other minor jobs like killing or driving the fishes from their hidden holes or places called ‘eyere’, usually covered with heavy woods. Might at that time was the sole criterion for seniority. This process took a lot of time for the completion of wrestling before the actual bailing. It became paramount to convert it into a wrestling contest which could be a game for entertainment that everybody could enjoy yearly. The bailing of the pond now became the wrestling contest known as Abame wrestling contest, which literally means, wrestling in or for water (water wrestling). It became a wrestling contest for age groups.The zeal for the contest compelled the individual to train very hard before the next one. It was in different categories – junior, intermediate and senior. The challenges were between different units of each kindred before the inter-kindred competition involving the two groups into which the town and its villages are divided. Within the main town, three kindreds are derived; Ekpo, Okphro and Uruwhre. Ekpo and Okpohro fall under one broad unit – Unuame (from the riverine) and Uruwhre falls under Okpara group (land). Other small villages forming Igbide clan are divided into these two groups as followsUnuame Group: Ekpo, Okpohro, Owodokpokpo, Egbo and UrovoOkpara Group: Uruwhre, Oteri and Agbawa (Lagos Igbide)Both groups have to select their most powerful, valour-endowed and healthy youths who have the techniques and skills of wrestling. The virgin land very close to the Atawa pond is usually chosen as the arena. This arena is never cut with matchets but trampled down with bare feet. It is assumed that some of the plants enhance the effect of charms and serve as catalyst for the charms used by each contestant. Usually on a fixed date in March, which is the dry season and a period conducive for bailing ponds, all the contestants, relatives, friends and well wishers converge in Atawa. At that time, costume used was individualistic, although it was still skirts (Ubuluku) of different variations. The rules or regulations of the traditional wrestling contest are quite different from the modern Olympic and professional wrestling. It is simple; a fall is determined by any part of the body touching the ground. And the argument is that man walks only on the soles of his feet, therefore, for any part of the body – hands, knees, head etc. to touch the ground means one has fallen. A defeated contestant was to pay homage to the winner whenever the next festival period was near with a basin of yams. In fact, the result of the contest was usually disastrous both for the winner and loser as fighting resulting in serious injuries was always the outcome.This contest later degenerated to two individuals. The most powerful, energetic and masculine person is selected by each kindred as the representative. This time, it was likened to the famous Greek Olympic Games where it was both for individual and national honour to win. It was ill-fated to lose. The shame and disgrace was for the individual and the kindred. Hence each group prepares series of charms of different types with various effects for their representative many days before the stipulated date. The contest was preceded by a procession from the individual kindred to Atawa, beating drums, dancing and chanting of war songs and discharging of dangerous charms. The defeat of one of the contestants automatically ended what would normally look like jubilation in Atawa. The action would become more provocative when the winning group danced home with joy and honour, singing satirical songs. The other side (the losers) would reply with stones, broken bottles, sharp objects, wood, matchets, and other dangerous weapons on their opponents. Many people came back home with a lot of injuries resulting from the struggle. Loss of properties such as jewelries, shoes, headgears etc. became the hallmark of such scuffles. It created real enmity among them.

5. The Change in Abame Wrestling Contest

- The governing council of the community then decided to change the system from wrestling to a dance and celebration for an age group. Therefore, in the nineteen fifties (1950s) the wrestling festival was modified from its former concept of wrestling, and substituted with a transitionary age-grade ceremony that marked the transition from the status of youth through initiation to that of an elder citizen of the town. To qualify for participation in this ceremony, all prospective initiates have to register immediately after the festival has ended. They are to undergo some traditional training within a stipulated period prior to the next festival which occurs once every four years.Some of the pre-requisites which determine the eligibility to register in the present modern Abame festival, is that the individual1. must be a freeborn of the community2. must also be a respectable character, not known to be a traitor, loafer (worthless fellow) or a thief who can face public ridicule, ostracism or total banishment;3. must be a responsible married man. At present, a young man who is able to make it early enough in life can enroll as a prospective initiate once he is able to fulfil all the obligations.4. must have the registration fee and other appendages that are expected to be paid to the elders of the kindred. However, it is not too expensive for any individual who wants to be an initiate, as they are regarded as communal developers. Those in the urban area have to delegate their friends, or relatives to act on their behalf whenever public services are required.Two weeks to the fixed date of the festival, all registered initiates are expected to come home for more serious training and preparation. This period is for socialization, relaxation and to discuss issues affecting them e.g. selection of materials and colours for the skirts (Ubuluku), and colours of caps. They formally select the best skilled, most active, energetic and devoted member to be their lead dancer, who will be at the front of the group on the festival day. The lead dancers may be two or three, depending on their performances.In every situation, there are always gate crashers or late registration of indigenes who are interested in the participation in the festival. They are highly fined according to their status and those who are able to meet up are allowed to join in the dance which the individual must learn.

6. Costume and Body Adornment

- Definitely costume is an extract of the cultural environment in which it is made. The Igbide people are predominantly food crop farmers and fishermen. And because they are agriculturists, a lot of their activities are energy-sapping, making use of their hands, waists and legs at the same time during toiling and planting seasons. The use of all muscles during weeding and harvesting is obvious. It is also clear that the occupational inconveniences have influenced their use of the bare body for the Abame dance, and also because the festival is held during the hot, dry season. It has been observed that the use of specific costume and body adornment restricts the gestures and movement of the dancer. Therefore Abame dance which needs vigour, energy and flexing of muscles requires the body to be bare for free movement, allowance for fresh air, and easy dripping of perspiration from the body. Also, most traditional dancers do not use shoes, and Abame is not an exception. The use of shoes makes the wearer to be sluggish in action and out of place. A comparison of the body adornment and costumes of the different groups, Unuame and Okpara, demonstrates the extent to which art forms rely on individual aesthetic choices made by the participants. The different art materials, costume and paraphaernalia used depends on the individual and the kindred.The Skirt (Ubuluku)From time immemorial the skirt has been the major costume used. The early skirt was made of raffia weaving, done in one by one plain weave technique, with the use of a small, potable raffia loom called Ewewe. It was not a uniform but that was the type of textile material in vogue at that time and many participants had different variation of colours with traditional dyes. With the advent of Christianity and exposure to clothing, participants decided to use any type of fabric with different colours for their skirts, for a proper display of skills and techniques. The priests’ families were not easily attracted to the new Christian religion. Therefore their types of body adornment and costumes were quite distinct from others. After the modernization of Abame, each kindred decided to have one specific fabric for the skirt. The velveteen (Ugubethi) was the common uniform used because of its popularity. It is usually a long piece of cloth of about three to four metres. It is gathered and a small long strip of cloth is placed underneath the gathered material at the upper part to secure it tightly to the waist of the dancer on the day of the festival. The fullness of the gather depends highly on the length of the cloth used.Today, the selection of the type and colour depends on the discretion of the participants and the category of those involved in that year’s initiation. In the 1982 edition, one of the kindreds used expensive lace materials for their skirts because of the highly educated and wealthy people that participated that year. The voluminous, elaborately gathered skirt with the expensive head-ties attached to the skirt suggests wealth and superior status. This makes it look more of a dance than a wrestling contest and the number of the head-ties depends on the number the initiate can afford. The attire provides more aesthetic appeal for the fat-bellied men than the slim tall one, although the latter are more agile and active. According to Nwoko (1979:3) [21], “the generalized African aesthetic taste in human forms is a preference for the big or fat. That a fat person exhibits a state of well being which is desired by all”. It is, therefore, not unexpected that most of the participants would want to add some flesh and have a pot belly as a fat man is generally believed to be healthier than a skinny one.Hair-doThe hairdos of the dancers are of different varieties because of their different beliefs and orientation. In the ancient days their hairdos looked more war-like with different types of feathers attached to what looked like a hat. It was not bought in the market but specially made by some traditional herbalists who wanted their children to be conspicuously attractive during the ceremony. Others used one or two feathers inserted into their hairs or caps.Today, a particular type of cap, the Igbo woven title cap, is generally accepted. The Igbo connection is traceable to the origin of Igbide as already stated earlier in this paper. Besides, majority of them were settled in Igbo land before the Nigerian civil war drove them back home (to Igbide).The lead dancer (Ogba), who is supposed to be more skillful in the dance, uses a different head gear. He has a fluffy woolen texture at the top, dangling down the neck to the shoulder or chest. The lead dancer(s) look(s) more fearful, agile, active and more aggressive in appearance.

| Plate 2. One of the lead dancers with his kid carrying medicinal herbs |

| Plate 3. A dancer with his kid carrying the pot of medicinal herbs |

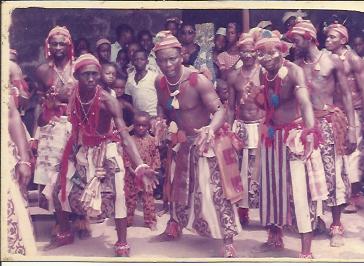

| Plate 4. Ekpo kindred group |

I have called youOkieriọ

I have called youOkieriọ He has fallenỌrotọ

He has fallenỌrotọ He is on the groundAt the end of the last word, he turns immediately and at the same time the king throws native chalk that falls on his back to mark his success. He joyfully dances back to join his group. Some of the styles incorporated in the dance are fierce, strenuous and strange. Occasionally one thinks they are fighting with some invisible opponents. Nevertheless, Uyovbukerhi, (1980: 100-101) [25] believes that with “the charisma or charms induced in him by the native herbalist, the wearer is easily able to disarm any hostile element or force that may be present during his performance. And that these magnetic powers affect the quality of his performance and he becomes very spectacular”. At least ten participants are expected to display the skills to the king and each time, the king usually throws the native chalk on everyone as approval after a successful display. It should be noted that those principal words must be said in that sequential order and failure to do so results in laughter, mockery and hooting from those who are aware of the implication of such failure. The emotional reactions of the festival are vital ingredients for dance, although they are usually embraced and preceded by larger dramatic substance drawn from the accumulated experiences of the whole community. But this is always consciously primed to serve social, religious and aesthetic functions as with all other art everywhere. It is noted that the three different levels of theatrical dance, high, medium and low are embedded in Abame festival dance which shows that it is well choreographed dance and the use of space in the arena cannot be over-emphasised. At the end of the dance of the last ten chosen to display their skills, all members are free to dance forward to the king for his blessing and then, they leave the arena.

He is on the groundAt the end of the last word, he turns immediately and at the same time the king throws native chalk that falls on his back to mark his success. He joyfully dances back to join his group. Some of the styles incorporated in the dance are fierce, strenuous and strange. Occasionally one thinks they are fighting with some invisible opponents. Nevertheless, Uyovbukerhi, (1980: 100-101) [25] believes that with “the charisma or charms induced in him by the native herbalist, the wearer is easily able to disarm any hostile element or force that may be present during his performance. And that these magnetic powers affect the quality of his performance and he becomes very spectacular”. At least ten participants are expected to display the skills to the king and each time, the king usually throws the native chalk on everyone as approval after a successful display. It should be noted that those principal words must be said in that sequential order and failure to do so results in laughter, mockery and hooting from those who are aware of the implication of such failure. The emotional reactions of the festival are vital ingredients for dance, although they are usually embraced and preceded by larger dramatic substance drawn from the accumulated experiences of the whole community. But this is always consciously primed to serve social, religious and aesthetic functions as with all other art everywhere. It is noted that the three different levels of theatrical dance, high, medium and low are embedded in Abame festival dance which shows that it is well choreographed dance and the use of space in the arena cannot be over-emphasised. At the end of the dance of the last ten chosen to display their skills, all members are free to dance forward to the king for his blessing and then, they leave the arena.  | Plate 5. A dancer demonstrating one of the dance steps |

| Plate 6. Dancers with different body adornments |

| Plate 7. Lead dancer of Uruwhre kindred with body adornment |

7. The Importance of Abame Dance to the Community

- Abame dance has been modernised to become an age-grade initiation ceremony that has developed the individual, kindred and the community in the following ways;1. From the discourse, one can deduce that everybody in the community is a participant in one way or the other.2. It has encouraged marriage institution as only married women who have been escorted to their husbands’ houses are allowed to follow the initiate-to-be in the procession, as they shower praises on their husbands.3. It is also done according to seniority, but where a son wants to dance before his father, the community will make the son to pay for his father’s participation first before he would be allowed to partake in the next event.4. Only initiated members are regarded as men and respected elders in the community. Hence, all professionals such as professors, doctors, lawyers, teachers as well as peasants must take part in this dance.5. In any socio-cultural gathering where money is given to the group or audience, only initiates are allowed to share the money.6. It is also noted that only initiates are given any social, administrative or political positions in the community. Chieftaincy titles are given to only initiates.7. At most important or social ceremonies, initiates are given preferential treatment. For example an old man who has not participated in the age-grade initiation (Abame dance) may be humiliated by being asked to vacate his chair for a younger man who has already being initiated.8. An uninitiated Igbide man who dies, even if already married will not be given a benefiting burial rite as he is regarded as a young boy.So because of the aforementioned factors all Igbide people from all nooks and crannies of Nigeria, those in diaspora (abroad) must come home for the performance of the dance. It is note worthy to say that the last Abame dance which was celebrated in March 2014 had a lot of participants from abroad. This is to show the world how important and prestigious the dance is to the community. This festival if well advertised and publicized, it will attract a lot of tourists, travellers and art lovers to the community, thereby resulting to financial gains for the individuals, community and the nation as a whole.

8. Conclusions

- It can therefore be concluded that costume and body adornment form the integral part of dance, and that dance steps or styles determine the type of costume or body adornment required. This again is subject to cultural acceptability and norms of the society. A good display of dance cannot be established except good costume and body adornment are used to enhance the dance and give it a meaningful interpretation.Abame dance has accomplished the usefulness of costume and adornment to dance as displayed by most of the lead dancers. The costume and body adornment of the dancers have shown the social stratification and aesthetic taste of the individual from their appearances. The lead dancers are easily identified from the others because of their peculiar costuming. The anatomical structures of both the fat, bulky, thin and slim individuals are visualized by the spectators as their bodies are exposed. Wealth and good health, which are always assumed to be associated with the bulky and fat-bellied people, are highly exhibited in Abame dance. The rhythm and the sequential movement of the dance has been enhanced and well appreciated because of the flow, movement of the skirts, head-ties, and fluffy woolen materials used by the dancers as body adornments. The uses of charcoal and native chalk coupled with bright colours of the costumes really instill fear, fright and puzzlement on the onlookers. Therefore from all indications, Abame dance has satisfied the objectives of costume and body adornment in dance, especially in its socio-cultural environment in which it is meant to serve. Most importantly the costumes and body adornment enhance the appreciation of the dance proper, and contribute to a better understanding of not just the dance and the festival, but the culture of the people in general.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML