-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Arts

p-ISSN: 2168-4995 e-ISSN: 2168-5002

2015; 5(1): 8-20

doi:10.5923/j.arts.20150501.02

History of Italian Immigrants Experience with Housing in Post WWII Australia

Raffaello Furlan

Qatar University, Qatar; University of Queensland, Australia, Griffith University, Australia; Canadian University of Dubai, UAE

Correspondence to: Raffaello Furlan, Qatar University, Qatar; University of Queensland, Australia, Griffith University, Australia; Canadian University of Dubai, UAE.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Previous studies on Italian migrants in Australia highlight that Italian migrants migrated to Australia in the 1950s’-1960s with the primary goal of permanently settling in Australia. Also, scholars pointed out that the form of the transnational houses they subsequently built in Australia were manifestations of both their wish to have their family united under the one roof and of the family’s economic success. In opposition to the work of previous scholars, this article, exploring Italian migrants’ narratives and views about their migration experiences in Brisbane in the post-WWII period, will instead argue that migrants did not intend to settle permanently after their first arrival in Australia, and that further meanings were embedded in the form of their transnational houses built in Brisbane, beyond that which reflected the unity and success of the family.

Keywords: History, Migration, Built Form, Vernacular and transnational houses

Cite this paper: Raffaello Furlan, History of Italian Immigrants Experience with Housing in Post WWII Australia, International Journal of Arts, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 8-20. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20150501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Vasta (1991) highlighted that for Italian migrants migrating to Australia in the post WWII period, the family was generally at the apex of their hierarchy of values, and that it had a crucial role related to houses’ ownership. More specifically, he pointed out that for Italian migrants, settling down in Australia was important in the context of having the family united and settled with a roof over their heads. In addition, in her studies of transnational housing, Pulvirenti (2000) notes that to Italian migrants, who had the highest home-ownership rates of all birthplace groups in Melbourne, housing was of great significance. She highlighted how this cultural group, once disembarked in Australia, had paramount the wish to settle down permanently and that home ownership was not only a way of investing income, but it was also a symbol of the ‘sacrifices’ made for the family, and consequently of their success achieved in Australia (Pulvirenti 2000). Depress (1991), who developed further research on transnational houses, reveals that transnational houses are interpreted as a place where migrants established a close-knit family, and where they tend to spend more time than the dominant group. Therefore, in these studies, scholars highlight the role of the family as a factor influencing Italian migrants’ decision of settling down in Australia and owning a house, and also how transnational houses are interpreted as manifestation of (1) the unity and (2) economic success of the family. In this paper I will explore and analyse the experiences and views of Italian migrants’ residing in Brisbane in order to reveal when and why they decided to settle and build their own houses in Australia. The meanings embedded in the form of their houses will also be investigated and revealed in this paper.

2. Methodology

- In order to collect first-hand data to answer the research question a detailed case-study was required. The case study included 40 Italian migrants (20 male and 20 female). The data was collected from February 2008 to December 2009 from oral stories from Italian migrants living in Brisbane through focus-group, semi-structured and in depth interviews. Interviewees were limited to migrants born in Italy during the 1930s and 1940s, who are referred to in this study as ‘first-generation Italian migrants’. All selected first-generation migrants had migrated to Australia in the 1950s and 1960s, that is, after the WWII reconstruction in Italy. Additionally, social class was a ‘limit’ that must also be taken into account. As Pierre Bourdieu (1992) argues, social and cultural priorities differ according to the social class people belong to. Those selected for interview could be broadly classified as working class people: they constituted the majority of Italian immigrants migrating to Australia in the post-World War II period (Cresciani 1985). In relation to the use of terminology throughout the article, in order to simplify the naming of “working class first generation Italian migrants” selected for this research study I chose to name the ground under investigation as “Italian migrants”.

3. Data Analysis

- The argument put forward in this paper is that (a) the period Italian migrants’ decided to settle and build their houses in Brisbane, the motivations behind their decision and (b) the meanings embedded in the form of their own houses are the result of (1) their initial migratory plan and expectations, (2) the natural and built environment encountered at their arrival in Australia, (3) the settlement and (4) dwellings' form found in Brisbane. Therefore, in the following sections I analyze Italian migrants’ views and narratives about the topics listed above in order to reveal when, why and how Italian migrants built their houses in Brisbane.

3.1. Italian Migrants' Immigration Plan and Expectations

- The interviewees stated that even in the period prior to WWII, conditions in Italy were dramatic and precarious. Participants discussed how in the lead-up to WWII, the Fascist dictatorship, led by Benito Mussolini, who was in power from 1922 to 1943, impoverished the Italian economy. The policy of Benito Mussolini and its effects on the population are also emphasized by historical scholars like Randazzo and Cigler who highlighted that, due to the alliance signed by the two dictators Mussolini and Hitler in 1933, Italy under its dictatorship had entered WWII on the side of the Germans (Randazzo and Cigler 1987). The impacts of this decision were far-reaching. Economically, the subsequent high taxes to fund the war effort drastically impoverished the population in the early 1940s. Interviewees highlighted that (1) the poverty the Italian population suffered during WWII cause of the fascist dictatorship was followed at the ruinous end of WWII by (2) a lack of work and (3) an overcrowding phenomenon, which had become common in many Italian cities in the post WWII period. This was caused by people migrating from rural areas towards cities, due to the lack of land to be cultivated in rural areas. Moreover, Italo stressed that the lack of agricultural land was caused by the Italian government political incapacity to distribute the agricultural land among the working class. The way the Italian government managed the land reform, which could help the national economy to recover, is also emphasized by Ginsborg (1990). In particular, he pointed out that the agrarian reforms, funded in order to reduce the large land owners’ hegemony in particular in the south of Italy and expropriate of thousands of hectares of land possessed by a few rich families in favour of the agricultural labourer with no financial resources, were blocked because of the difficulty to remove the old fascists from the bureaucracy. This worsened Italian population living conditions because landless labourers were forced to move towards the cities to search for work.Harper and Faccioli highlight that in Sicily the agricultural land could not support the entire regional population and this encouraged Italians from Sicily to migrate towards more prosperous destinations. As also stated by Castles, this phenomenon occurring in other regions of Italy was one of the main reasons to leave the homeland.Neither the peasant movements of the 1940s, nor the Christian democratic government’s attempts at land reform and industrialisation from the 1950s, did much to break through the age-old cycle of exploitation, poverty, corruption and homelessness. Emigration was the only way out (Castles 1992). Paolo and Vittorina also pointed out that after WWII many Italians found themselves (4) homeless and consequently were forced to live in shacks, barracks, schools and camps, since their houses were severely damaged during the German and Allied bombings in 1944. This is also acknowledged by Rosoli, who states that during the final period of WWII the Italian partisans, as military formations of the Italian resistance movement opposed to Nazi-Fascism in Italy, fought the Germans and the formations of the ‘Fascist Italian Social Republic’. The Germans, in their slow retreat, caused as much destruction as they could to punish the Italian people for having overthrown Mussolini and welcoming the allies. Additionally, the Allied forces brought ruin to Italian cities and countryside through a programme of intensive aerial bombing to defeat the Germans. When WWII finally ended, the Republic of Italy following its defeat, was included by the United States into the ‘European Recovery Program’ or Marshall Plan, to allow Italy to move towards the reconstruction (Rosoli 1978). As many interviewees stressed, the reconstruction process encouraged through the Marshall plan took longer than expected. The reconstruction process was slow in terms of infrastructure and particularly uneven in terms of housing distribution.In addition, many interviewees sadly remember the (5) shortage of food they experienced during and after WWII. The food scarcity problem in Italy in the post WWII period is also stressed by Harper, Faccioli and Ginsborg. They highlight how in the post WWII period there was great poverty in cities as well as in rural areas, and that generally in Italy food was scarce due to a large population and also to inefficiency in the way it was stored and distributed. Italy’s economy declined in the nineteenth century, which led to chronic food shortages that lasted until the 1950s. The population was too large for the agricultural system; surplus food was inefficiently stored or distributed; the government taxed agriculture and food and encouraged production for export, even in the face of shortages (Harper and Faccioli 2009).By the end of the war, Italy was one of the poorest countries of Europe. The rationed food available per person was 1160 calories in 1941 and dropped to 990 by 1944. Most Italian agriculture remained a peasant system based on sharecropping, land rent, and daily labor. After the war, peasants from across Italy agitated for land reform, access to land owned by deposed fascist landowners, and, more simply, food and jobs (Harper and Faccioli 2009).Therefore, from the evidence collected I summarize five main factors which encouraged the interviewees to leave the native country and to migrate towards a host nation. Emigration for Italians was motivated by (1) poverty due to the pre WWII Fascist dictatorship and to the ruinous outcome of WWII; (2) the lack of working opportunities in Italy; (3) the overcrowding phenomenon which occurred in the Italian cities; (4) the loss of or the damage of the family house; (5) and finally food shortage.Interviewees conveyed that their common desire to leave Italy was also facilitated by the Italian Republican government, which in the 1950s approved a favorable migratory-policy in order to encourage the Italian people, namely those who were poor and unemployed, to migrate towards foreign nations, such as Australia, Canada and Argentina, which required additional workforce due to labor shortage. In March 1949 a report to the Italian Department of Emigration explained that the population was exceeding the economic resources and structures of the country by almost four million. Therefore, the Italian government assumed that migration could relieve amounting pressures caused by overcrowding and unemployment. Consequently, encouraged by the new Christian Democrat Prime Minister, Degasperi, Italy started looking for overseas countries as possible emigrating outlets where Italians, who could not find employment at home, could move to live and work (Ugolini 1991). Furthermore, the government assumed that Italians migrating overseas could eventually provide the financial support to their struggling families in Italy and therefore could also be of assistance to the Italian economy (Cresciani 1985). Finally, in 1951 the Italian Prime Minister put in place a policy to encourage an exodus of Italian emigrants to Australia. If in Italy the post WWII industrial production had diminished and millions of people were unemployed (Baldassar 2005), Australia was facing the opposite problem - labor shortage - due to rapid agricultural and industrial development. In Australia, like in most European countries, WWII placed great strain on the economy. For nearly six years the industry had been mainly producing war weapons and WWII caused the deaths of thousands of Australians who were part of the workforce (Castles, Alcorso et al. 1992). Therefore, in July 1945, the new appointed first Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, aiming at overcoming the Australian small population problem, embarked on a ‘Populate or Perish’ program which would increase the country’s population and build up its manufacturing and industrial resources (Church 2005). Randazzo and Cigler stated that in 1945, due to shortage of labours, the first country that Australia turned to in order to get migrants was Britain because Australians believed that people from Britain could most easily and speedily assimilate into Australian society. However, the number of migrants coming from Britain could not satisfy Australia’s demand. Consequently, the Australian Government profoundly changed its immigration policy in order to encourage large scale migration of nonEnglish speaking people from several countries. The aim was to increase the Australian population in order to develop the continent and to defend it in the event of an invasion (Randazzo and Cigler 1987).In 1951 the governments of Italy and Australia agreed upon a bilateral immigration-scheme which provided Italians with assistance with the cost of migration into Australia (Bosworth 1996). In the years following the bilateral immigration-scheme, the number of Italian arrivals in Australia increased significantly. The 1950s was the peak decade of Italian migration to Australia. This made the Italians the second largest cultural group behind the British (Bosworth and R.Ugolini 1992; Ruzzene and Battiston 2006). The 1950s Italian government’s decision to advertise this opportunity to migrate overseas was interpreted as a way to give unemployed and poor Italian population a hope for a prosperous future. Interviewees highlighted that migrants were simply offered the opportunity to travel away from the ruins of Italy, work abroad for a few years, and then return with an economic security to a nation which would have recovered from the outcome of WWII. Migration had a distinct meaning to the Italian people in the 1950s: it meant migrating to America! It did not matter whether North, South America or Australia was the actual destination or not. According to the interviewees, the term ‘America’ was used regardless of the destination since it carried a general meaning. That is, America stood for the dream that prosperity, wealth and well-being could be attained within a few years. This idea of ‘America’ being the ‘dreamland’ was influenced by the recognition that America also was the ‘winner’ of WWII and Italy, on the contrary, had been left in ruins. Interviewees stated that, in Italy, after the 1945 death of the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, the Americans (or the Allies) disembarked in Sicily and Lazio and fought the invading Germans. Therefore, the Americans were recognized as the ‘rescuers’ of the Italian people. Moreover, interviewees pointed out that United States had been exercising a powerful positive influence on the Italians even before the 1950s. Interviewees recalled that many Italians migrated en masse to cities like New York and Chicago in the 1920s after WWI and some of them, after becoming very rich in the United States, returned to their home town in Italy. This enhanced the myth of prosperous ‘America’ among the Italian people who were willing to migrate in the 1950s. So, even though in the 1950s, the United States of America closed its doors to immigration of Italians due to the significant waves of Italian immigration taking place in the 1920s, and therefore Italians were allowed to migrate only to Australia, Canada or Argentina, America was still in Italian people’s minds. In relation to the duration of their contemplated permanence in Australia, all interviewees clearly stated that they did not intend to leave permanently ‘la madre patria’ (the homeland). Their initial plan was to leave Italy for a period varying between two and five years, just to improve their personal financial situation and that of their families back in Italy. Interviewees revealed that they thought that this period away from Italy would have allowed them to return after a few years in a better financial position and finally to settle in Italy. Amedeo, while showing a photo of the ‘Fairsea’ boat (Figure 1) when he left the port of Trieste in 1954, talked about his initial plan to stay away from Italy just for a five year period. The feeling of uncertainty for the future in Australia was dominant in the memory of most interviewers. Migrants were about to leave the safety of their homeland and their families, for an unknown land promising to fulfill a dream of prosperity. Moreover, as interviewees confided, the feeling of uncertainty intensified Italian migrants’ initial intention to not migrate and stay permanently in Australia.

3.2. The Natural and Built Environment in the Sugar Cane Fields

- The majority of Italian migrants interviewed stated that they came from rural communities, where, as Salvatore mentioned, ‘Italian migrants acquired a wealth of practical knowledge, experience and skills’ (2:18). Salvatore and several interviewees also pointed out that they migrated to Australia on the assisted passage scheme, which obliged them to accept any work offered to them anywhere in the country for a two-year period. Antonio confirmed that upon their arrival in Australia, due to their rural background, Italians were able to turn their hand to agricultural activities, viticulture and farming.The literature also revealed that the decision of many migrants to work in the agricultural sector was influenced by their professional background: most Italians who arrived in Australia in the post WWII period came from the agricultural areas of Italian poorer regions like Abruzzo, Campania, Calabria, Sicily and Veneto (Church 2005). Panucci, Kelly and Castles revealed that a large proportion of Italian migrating to Australia was shopkeepers and farmers, and by 1966, the majority of Italian migrants in Australia worked as low-skilled labourers. Therefore, it does not surprise that the jobs Italian migrants found upon arrival in the agricultural sector reflected their professional backgrounds (Cresciani 2003) (Panucci, Kelly et al. 1992) (Ruzzene and Battiston 2006). Most interviewees stated that upon their arrival in Australia in the 1950s, the most labour was required in the sugar cane industry in North Queensland. Therefore, as mentioned by Carmelo, many Italians flocked to North Queensland in search of well-paid seasonal work as sugar cane cutters.Apart from their agricultural-rural background, interviewees highlighted another aspect which encouraged them to embrace a job on the sugar cane fields in North Queensland: their single status. Scholars pointed out that in the post WWII period Italian men migrated in larger numbers than females in Australia because Australia required men for unskilled labour in primary and secondary industries; women generally migrated in a second stage through sponsorship by husbands, and/or relatives (Panucci, Kelly et al. 1992). This was confirmed by the interviewees who stated that most of those who migrated to Australia were single males. As a consequence, at their arrival the search for work took migrants to the remotest corners of Australia, where a labour force was required and wages were higher.Interviewees mentioned on several occasions how on the sugarcane fields in North Queensland they found the promised very well-paid work they had come for from Italy. Salvatore, who spent seven years in the sugar cane fields, talked of labouring from dawn till dusk under hazardous conditions. He stressed how Italian migrants found an unfamiliar and unexpected (1) wild natural environment in North Queensland, and that he and other migrants working on the sugar cane plantation had to struggle with unusual animals, in particular, venomous snakes.Cutting the sugarcane was very dangerous because there was the ‘bloody’ venomous brown snake and the red-bellied snake. In our plantation a few got bitten by those dangerous snakes but no one got killed, thank God! We saved some people by pure miracle. You know, sometimes snakes were also inside our house. We found one in the kitchen cabinet board, and another one in the bathroom. We were always scared for our kids…we were used to losing a dog every couple of months, although we did not want to lose a kid (Transcript 2:09)Salvatore showed a photo taken in 1958 of him with some friends, which highlighted the Italian migrants’ unfamiliarity with Australian wildlife such as snakes (Figure 3). However, Teresa showed a photo where she is nearby a dead snake (Figure 4). She pointed out how after the initial period of adaptation to the natural environment, migrants became accustomed to living and working around the wild animals that they encountered.

| Figure 5. The shed on the cane fields. Aldo stated that in the 1950s most single Italian migrants working as cane cutters in north Queensland shared a shed with other workers. (Photo from case 3) |

3.3. The Settlement Form in Brisbane

- As interviews mentioned, after a period varying from five to ten years, many Italian migrants realized that work could not fulfill their entire lives, and consequently, they wanted to improve their social lives. Italian migrants assumed that the city could offer a chance of interacting with more people since it would provide the urban environment capable of facilitating social interactions which migrants lacked while living in the sugar cane fields.Both those interviewees who moved to Brisbane from North Queensland in the 1960s and those who arrived directly from Italy in the 1950s, stated that upon their arrival in Brisbane, they encountered some differences in the host built environment which, in their view, hindered their ability to interact socially with other people. More specifically, interviewees stated that the first difference compared to their native country built environment was represented by a missing urban public element such as town squares which, in Italian migrants’ opinion, allowed interactions with other people. Respondents highlighted how in the Italian built environment, it was quite common for dwellings to be arranged around a central courtyard or town square-plaza, which reflected a strong sense of community among residents.

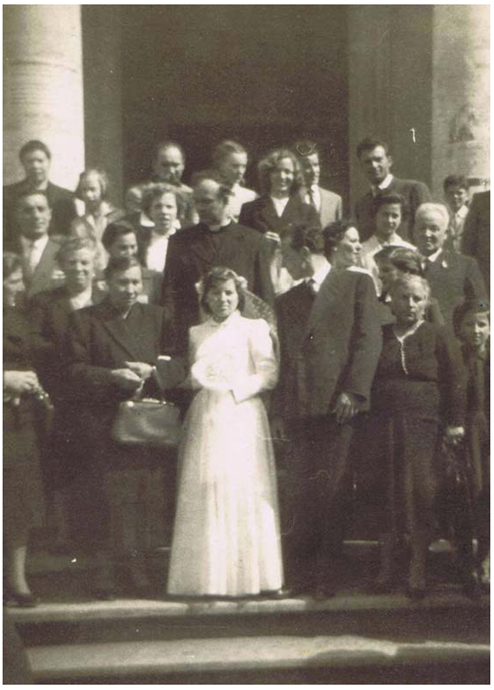

| Figure 7. Marriage by proxy. Concetta married by proxy in 1957. The groom, Domenico, was afterwards inserted in the family picture. (Photo from case 5) |

| Figure 8. Chain migration. Domenico’s brother (second from left) and sister (first from right) migrating to Australia in 1959 with their families. (Photo from case 5) |

| Figure 11. Dinner at the Italian Club. Italian migrants met at the club on a regular basis to enjoy each other’s company, celebrate anniversaries and birthdays. (Photo from case 12) |

| Figure 12. The bocce game. The Italian Bocce Club is situated next to the Italian Club building. (Photo by the author) |

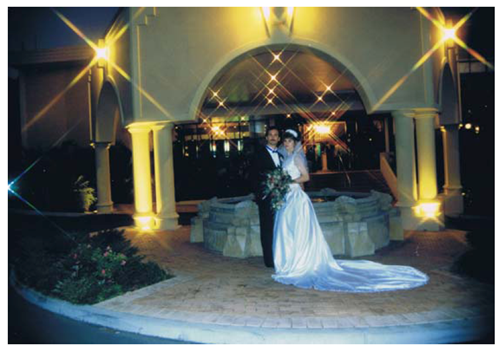

| Figure 14. Wedding reception at the Italian Club. The wedding receptions for many second generation Italian migrants were often held at the Italian Club in Newmarket. (Photo from case 18) |

3.4. Dwellings’ form in Brisbane

- After exploring the difficulties and differences related to the built environment Italian migrants encountered at their arrival in Brisbane, I enquired about the form of the dwellings Italian migrants resided in since their arrival in Brisbane. Carmelo, stated that, in a similar case as to many other interviewees, upon his arrival in Brisbane in the 1950s the best option was to rent an existing property, since he, as all of his friends, were seasonally employed – in market gardening, poultry and pig farming, horticulture and viticulture – without regular job with a steady income. Furthermore, other interviewees like for example Italo and Antonio, clearly highlighted that in the early 1960s they were not committed to settling in Australia: they still had in their mind the wish to spend a period varying from 5 to 10 years in Australia and then return to Italy. Therefore, as stated below by Italo, in the early 1960s they were not intending to settle, buy or build a house but keep on renting for a few more years up to their return to Italy.We rented because, when we arrived in Brisbane, we wanted to stay just for a few more years. Not for too long. You don’t want to buy a house just for a couple of years, do you? And then leave the country! (Transcript 12:24)Many interviewees stated that, after an initial permanence varying from 5 to 10 years where they rented existing houses, they decided to stay for further 5 to 10 years in Australia to consolidate their financial assets. Therefore, many interviewees stated that in the late 1960s they opted for purchasing an existing house with eventually the ultimate aim to renovate, extend it and eventually sell it. For example Assunta and Pasquale, after purchasing their first property in 1967, decided to renovate the house. As Pasquale showed in two photos (Figure 17-18), there were not many external Italian influences that affected the new look or the façade of their renovated Australian house. Pasquale explained that he mainly renovated the internal space of the house and externally he just replaced the timber posts supporting the ground floor timber slab with a brick wall. Renting was always a ‘sistemazione temporanea’ (temporary settlement). We did not like the idea of wasting our money in renting. Unfortunately we did not have enough money to purchase the land and build a new house. It was too risky to invest all your money in a big property. Therefore after a few years, we purchased a timber house (Figure 17). The house was standing on timber posts. It was empty at the ground floor. We enclosed the space at the ground floor with a perimetral brick wall (Figure 18) (Transcript 14:29).Salvatore also pointed out about his experience in renovating and extending an existing house which he purchased in the 1970s in New Farm (Figure 19-20). And, as mentioned below, he stated that in the 1970s renovating and extending existing timber houses became common among Italians residing in New Farm who aimed to then sell the renovated house.

| Figure 17. Existing weatherboard house |

4. Findings

- The summary of findings is structured into two themes: (1) the period of construction and the reasons behind the decision to build the house in a specific period; (2) the meanings embedded in the form of Italian migrants’ houses.

4.1. Settling the Family Permanently in Australia and Building a House

- As mentioned earlier, interviewees revealed that at the end of WWII they originally planned to migrate to Australia to accumulate the financial resources in order to return back to Italy and to build a house and/or open a business. Despite their original plan, interviewees stated that initially they extended their permanence in Australia for a further period of five-ten years, namely due to the fact that the Italian economic post WWII recovery took much longer than expected. Participants highlighted a phenomenon happening in the 1970s in Italy which influenced Italian migrants’ to leave Australia and to return to Italy. They stated how after spending a period of ‘tanto lavoro e risparmio’ (hard working and savings) varying from ten to twenty years, in the 1970s many Italian migrants were tempted to return to Italy and finally many of them returned to live permanently in Italy as originally planned. Also, Paolo pointed out that many Italian migrants among his friends went back to Italy because finally, after more than twenty years of recovery, the economy in Italy started booming again. In relation to the 1970s Italian economic boom, Cresciani also pointed out that after the post WWII period of intense hardship, Italy made a stunning recovery in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. Economic reconstruction was followed by unprecedented economic growth between 1950 and 1963, a period known as the economic ‘Italian miracle’ (Cresciani 2003). Italy concentrated on economic reform and consequently in the 1970s the country created and maintained a strong and sustainable economy. According to Cresciani, due to the 1960-1970s period of great economic prosperity in Italy, in the late 1970s many migrants who already spent a few years in Australia decided to return to Italy and to settle in their own native towns. Cresciani stressed that the prosperous economic conditions of Italy in the early 1970s gave many migrants a chance to invest what they earned in Australia in their own businesses in their mother country (Cresciani 2003). This was confirmed by many participants interviewed for this study who pointed out that many Italian migrants returned to Italy in the 1970s due to the favorable conditions.However, as participants stated, among those who went back to Italy, not all of them succeeded in their return and therefore after spending approximately a year in their native country they returned to Australia. Interviewees highlighted that several Italian migrants who attempted to return to Italy in the 1970s, realized that, after spending nearly twenty years in Australia, it would have been difficult for them and for their descendants in particular to adapt again to the Italian way of life which inevitably had changed since their departure occurred twenty years earlier. Interviewees stated that after having carefully evaluated the opportunity to leave Australia to return to their home country or eventually after having tried to, at the end of the 1970s Italian migrants embraced the prospect of permanently settling in Australia. Italy was far away, not just in terms of distance, but also in terms of way of life. In turn, interviewees revealed that the decision matured in the 1970s to settle in Australia encouraged Italian migrants to build their own new houses in Australia not as a temporary measure or for an investment, as many migrants previously did when they purchased, renovated and extended existing houses in the late 1960s, but for life. Therefore, the houses built only in the late 1970s-early 1980s became the answer to the Italian migrants’ wish to settle permanently in Australia with their families.

4.2. The Meanings Embedded in the Houses built by Italian Migrants

- As all interviews stated, the decision to build a new house on a building plot was not just dictated by the desire to be more independent, secure and settled, which could have been equally achieved also by purchasing an existing old or new house, but simply by the wish to have a house designed and built in response (1) to the family specific and/or cultural needs, dictated by a way of life.Participants, who purchased an existing house before building their own, pointed out the disadvantages they encountered in renovating an existing house, including the limited freedom in making internal or external modifications to the house. This limitation caused some inconveniences: the floor space was limited and family members needed more space (2) for performing social activities, which, as revealed, were limited by the lack of public open spaces like town squares. Apart from the idea of having a new larger house designed per their needs, all five couple interviewed pointed out the value and prestige of building a house on a building plot. Flavia and Aldo (Transcript 3:85) highlighted that, as many other Italian migrants, they were attracted by the idea of owning a piece of land. History showed that Italians in the 1950s came from various parts of Italy where land was not available, either for agriculture or building purposes. Therefore, migrants saw this investment as a (3) prestigious way to settle permanently with their families in Australia. As pointed out by Filomena for example, a new self-built house was also a way to show that, after years of hard work, the family had reached (4) a certain level of success. Anna and Italo mentioned below a further aspect which influenced Italian migrants towards the construction of a new house. The new house they built represented a sort of legacy for their descendants: their self-built house was supposed to become (5) the new family-house, as in the Italian tradition or as the house they lived in before departing Italy.Interviewees emphasized that another factor which encouraged them to build their new houses was the construction material and technique. Aldo, Domenico and Salvatore stated that “fully brick and concrete houses” were uncommon in the 1970s-1980s. Moreover, all interviewees pointed out that the majority of existing houses available for sale in Brisbane were represented by weatherboard and brick veneer houses, generally partially built in timber. Despite this, interviewees who built their own houses stated that they did not accept the prospect of living in a timber house and they wanted to build (6) a brick-cavity wall house.

5. Conclusions

- All interviewees clearly stated that in the 1950s, when they were offered the opportunity to migrate for a more prosperous future, they did not intend to permanently leave Italy and settle in a foreign country, in this case Australia. Their plan was to migrate to Australia for a period varying from two to five years (a) to financially help their families back in Italy, (b) to accumulate sufficient funds, in order to return to their homeland, Italy, (c) to build a house for their own new family and/or open a business. This explains why in the 1950s the great majority of Italian migrants migrated to Australia without their spouses and/or other families members. Indeed, migrants highlighted that it was their status as single in Australia which encouraged them to accept well-paid jobs to be performed in isolated natural and built environment, like in the sugar cane fields in North Queensland. Thanks to their high salaries, migrants could send money to their spouses and family members in Italy and saving for building their houses at their return.Despite their initial plan, in the 1960s family members and spouses arrived in Australia, approximately five to ten years after the first migrants’ departure from Italy, through a ‘chain migration’ process, since of the abundance of work in Australia and the need of laborers, and also to fulfill the feeling of isolation that the first migrants experienced in Australia. Nevertheless, even though in the 1960s families were finally united in Australia, and after years of hard work migrants had already saved enough money to purchase or to build a house, most of them did not intend to settle in Australia yet and, therefore, did not purchase existing houses or build their houses in Australia. The findings revealed that Italian migrants purchased their first houses in Brisbane in the early 1970s, mainly as an investment and not as manifestation of their wish to settle. It was only in the late 1970s early 1980s, approximately twenty-thirty years after their arrival in Australia, after having tried to return to their homeland due to the favorable economic circumstance in Italy, that migrants built their own houses, mainly as a manifestation of their will to permanently settle in Australia. Also, the findings revealed that the form of the house built by Italian migrants was shaped in response to (1) the family specific and/or cultural needs, (2) the need to create space for social activities, (3) the wish to achieve a prestigious plan, (4) to show the family success and (5) to have a family house, (6) and finally to have a house built in concrete and bricks. These meanings embedded in the form of their houses were influenced by their migration experience, namely by living in their previous built environment and houses, both in Italy and in Australia.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML