Zahra Abdollah1, Hasan Bolkhari Ghehi2

1Ph.D. Student, Shahed University, Tehran, Iran

2Associate Professor, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Zahra Abdollah, Ph.D. Student, Shahed University, Tehran, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The medieval era of 14th to 17th centuries A.D. in Islamic land of Persia is prominent for the abundant schools of thought, mysticism and theosophy. The era is also significant as the zenith of Persian art as the great miniature schools, such as those of Herāt and Tabrīz, flourished in this period. The enigmatic and symbolic notion of color, alongside form, plays an intrinsically deep role in achieving this prominent status, whose allegorical meaning should be deciphered according to the cultural and spiritual mood of that era. Notably, several miniature masterpieces of this period are wrought in spiral structure, a mystical symbol for mapping the cosmic journey of the soul. The present article underlines this mystical formation as an integration of the color aptitudes, as well as the aesthetical resemblance of the attainment of the knowledge of Reality (ma’rifat ul-Haq), which is the ultimate objective of the Islamic mysticism and theosophy. It is argued that artistic elements of color and spiral structure are not employed in Persian miniatures merely as decorative apparatus, but also enjoy certain symbolic rationale behind its high iconographic pretense. The aesthetics of color in Persian miniature, including the visionary effects, the symbolic connotations and accentuation, and the induced sense of harmony, balance and motion, are discussed and the spiral structure is argued to integrate these sentiments, by bridging to the spiritual ascent and its threefold manifestations in the religious code, Gnostic way and reality, resulting in a unification of inside and outside and coalition of the horizon and the soul.

Keywords:

Persian miniature, Color aesthetics, Spiral structure, Islamic mysticism

Cite this paper: Zahra Abdollah, Hasan Bolkhari Ghehi, “Aesthetic of Color and Connotations of Spiral Structure” (An Assessment of Medieval Persian Miniature), International Journal of Arts, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 17-23. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20140401.03.

1. Introduction

Persian art, in general, and miniature, in particular, place a high value for beauty. This is accentuated with such devotion throughout centuries that it has fabricated a counterfeit impression that Persian miniature is primarily an art of decoration. The royal patronage and sustained excellence have paved the ground for the conclusion to be taken for granted. In Persian painting, life and art are amalgamated with mutual inspiration, lending each other a hand to accord the splendor to the highest status, absorbing the artist’s uttermost, with incredibly little thought of individual pride and glory. Here, decoration is more a resource than a goal, as it endeavors to entertain the mind more so to merely delight the eye. It skillfully mingles, with delicate sensitivity, and solid stance with free rhythmic flow, yet it is well aware of its limits. One characteristic of Persian miniature, which makes it hard to comprehend, is the symbolism behind its full-fledged iconographic appearance. Symbolism at the same time clarifies and interprets reality and controls it. In this sense, it is capable to conceal as much as it reveals, and this is more so, when it is sanctified by custom and religion. In Persian miniature, the twofold character of the underlying symbolism is yet enriched with a third mode, a universal untold principle unifying the exoteric and esoteric, by recalling the principles that govern the order of life. This is where logical meets the beauteous and the banal duality between body and soul fade away. The color aesthetics and the symbolic connotations of structural elements in the medieval Persian miniatures are subject of long standing debate. Many scholars, including S.T. Arnold, B. Gray, L. Binyon, and J.V.S. Wilkinson, more or less regard the medieval Persian illuminations as a royal art with mere decorative incentives, “that is an expression of the taste, idiosyncrasies, power, prestige, and political assertiveness of a given prince or dynasty.” [1] A perusal analysis of the medieval Persian miniatures suggests various functionalities for color. This could shed a light on existing contrary advocates on the role of color in Persian painting. In assessing the influence of color in painting, some like A. Popes go as far to claim that “the color is but an adornment of the pattern.” [2] Nonetheless, the contemporary scholar, Michael Barry acknowledges that “the very existence of Persian miniatures with careful usage of variant colors addresses the innermost religious enigma of Islam.” [3] The debate on the connotation of artistic elements in Persian miniatures is not restricted to color. There is also a wide range of interpretations on the significance of form and structure. Spiral is a structural element whose possible connotative implications is ignored by some critics, while others like Purce, noted that “the spiral is the natural form of growth, and has become, in every culture and in every age, man’s symbol of the progress of the soul towards eternal life…It constitutes the hero’s journey to the still center where the secret of life is found. As the spherical vortex, spiraling through its own center, it combines the inward and outward directions of movement.” [3] This article discusses color aesthetics and symbolic connotations of the spiral structure in the medieval Persian miniatures. The discussion is based on the aesthetical effects of color and its role in stimulating a sense of accentuation and harmony, as well as movement and change. The spiral structure is argued to function as a mean to convey all the above sentiments, via making a bridge to the spiritual ascent with its threefold manifestation in the religious code, Gnostic way and reality, and resulting in a unification of inside and outside and convergence of the horizon and the soul. The main features of the aesthetics of color in Persian miniature, as listed below, include the visionary effects, the symbolic connotations and accentuation, and the induced sense of harmony, balance and motion.

2. Aesthetics of Color

2.1. Generating Visionary Effects

Regardless of any sophisticated connoisseurship, Persian miniature is simply beautiful, extensively due to its illuminating splendid colors. In this way, aesthetical attitude encounters two approaches:

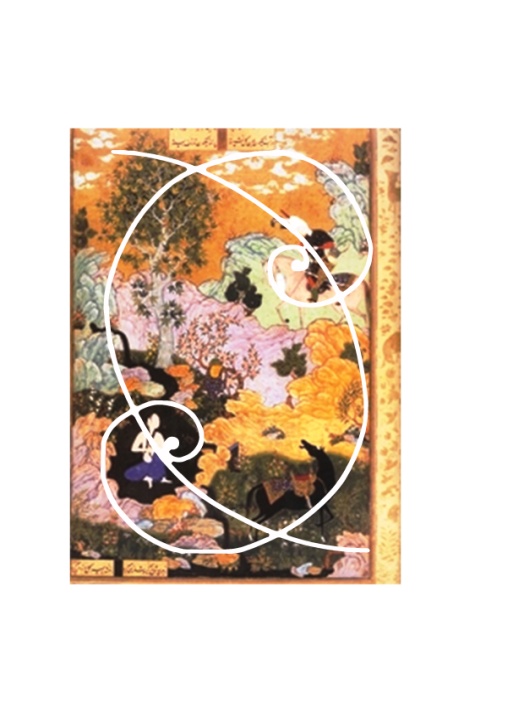

2.1.1. Expression of Quality (as in Figures 1 and 2)

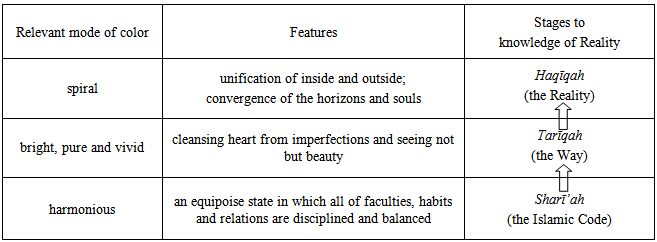

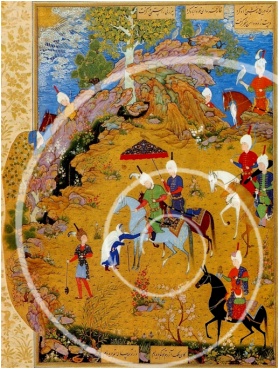

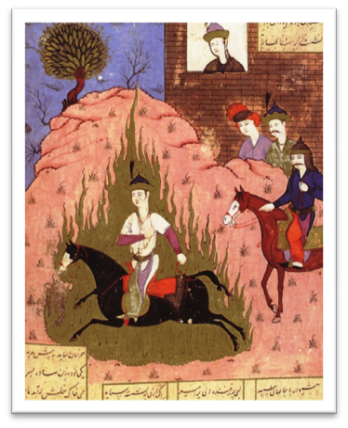

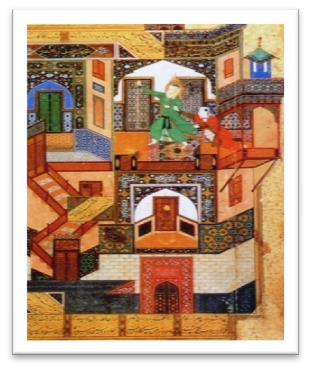

Color is a natural characteristic of any object, and miniaturists, based on this fact make things anonymous or acquainted. Color also reveals the object’s status, for instance redness of a flower calls out freshness, whereas a green tomato conveys that it is not ripe. In sum, color like smell, taste, sound and shape is a qualitative and not an intrinsic characteristic of the object. | Figure 1. Ardeshīr and Golnār, illustration to Buysonghori’s Book of Kings, Herāt, 833 A.H. |

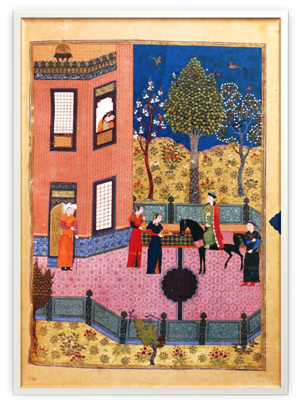

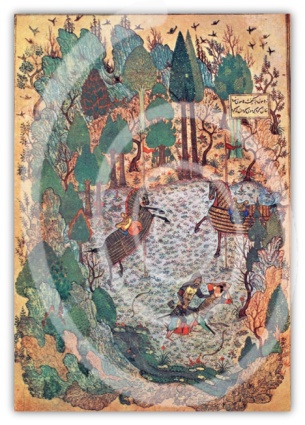

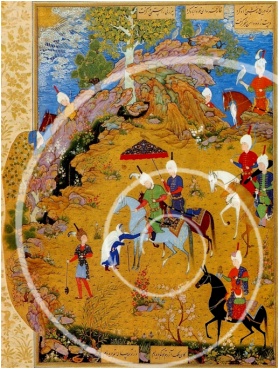

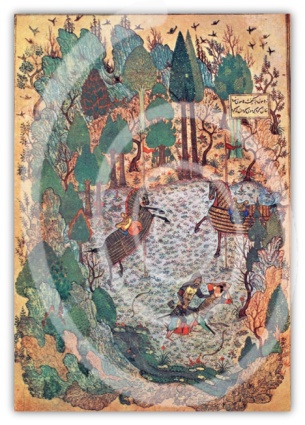

| Figure 2. Majnūn in desert, illustration to Tahmaāsbi’s Khamseh, by Āghā-Mīrak, Tabrīz, 948 A.H. |

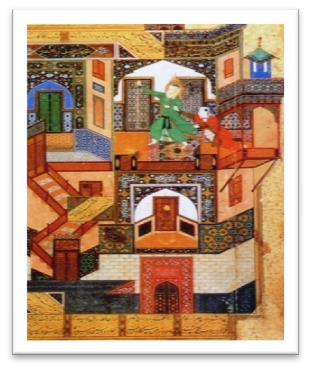

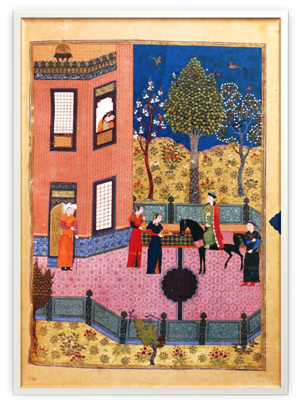

2.1.2. Decoration (as in Figures 3 and 4)

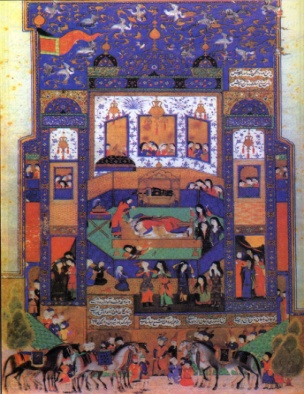

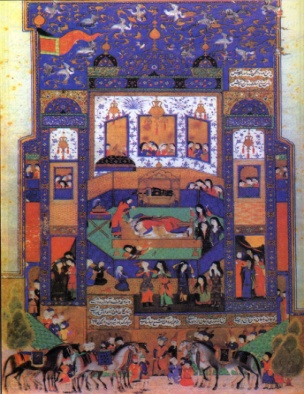

Commissioned by royal palace or major political authority, many flamboyant illuminations prospered to depict the ruling Sultan or Caliph of the day. This accounts for employing rare and precious color pigments to embellish these exuberant illuminations. Color tinctures, such as lapis lazuli pigment and “the many flecks of silver and gold which the artists burnished with polishing instruments fashioned out of ivory, onyx, or jade, are what in actual effect turn Persian miniature into a jeweler’s art.” [1] Nevertheless, the Islamic art critic, Oleg Grabar, declares that this ornamental treatment of colors is a connotation of the divine principle which asserts that subsistence is the absolute domain of Allah. [4]  | Figure 3. Josef and Zulaykhā, illustration to Sa’dī’s Bustan, by Bihzād, Herāt, 893 A.H. |

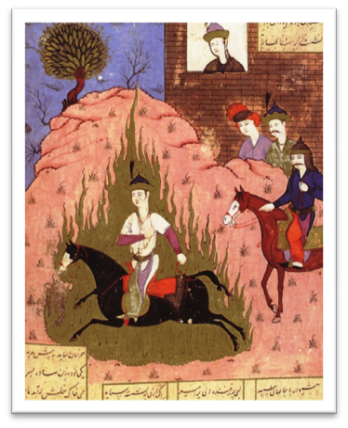

| Figure 4. Sultan Sanjar and old widow, illustration to Nizāmī’s Khamseh, by Sultan-Muhammad, Tabrīz, circa 918 A.H. |

2.2. Symbolism

A variety of religio-historical and psychological interpretations of color symbolism is plausible and advantageous. Somehow, light-color association stands at the threshold of this discourse. “All religions are in accord with applying the term light to the essence of divinity, then color, as a manifestation of light, can only signify the divine in its manifestation.” [5] Perhaps the most general symbolism of color in Islamic art, especially in Persian miniature, denotes plurality. Of course the preceding postulate is expected to regard light as symbolic representation of Unity. Indeed, “Plurality in unity and unity in plurality” is the eminent enforcing theme of many Islamic art pieces, from tiling in architecture to masterpieces of painting. Moreover, deploying a shiny diffused light throughout the page with the absence of an obvious source in all illustrations of this period and variety of pure glimmering colors testify to such a premise. This leads to another eminent attribute of Persian miniature, namely the absence of void in illustrations. [6] The artist deliberately leaves no uncolored space in order to credit every minute detail as part of this plurality. Any individual color on the surface of paper could impose a specific allegorical meaning. This is the case for several miniatures, depicting episodes of Heaven and Hell, where the domination of golden in former, and black in latter signify the incessancy of felicity and ordeal in the hereafter. Moreover, the golden halo around the heads of saints in these figures, and many other illustrations, is a symbol of the light of glory (farr, in Persian). No in depth discussion of the Persian miniature and allegorical meaning of color can proceed without reference to Persian literature, among which Khamseh of Nizāmī occupies an special place, as it involves a great deal of issues related to color. The book was indeed also “the most lavishly illuminated of all Islamic books by the fifteenth century.” [1] Here to assess the symbolism of color in Khamseh, the miniature of Death of Shīrīn (Figure 5) is taken into account. This harmonious outcome of the Turkmen school of painting visually revives the last episode of Nizāmī’s Khosru and Shīrīn, one of the Five Treaures of the poet. The queue of mourners and the dead body of Shīrīn dubiously contrasts the intoxicated flight of the angelic birds on the top of the scene. According to the poems, Shīrīn, depicted in red as a symbol of pure desire, is the self-indulgent martyr of love. This mystical notion is symbolically conceived by a red wavy flag, an insignia of venerable martyr of Karbalā, at the upper left corner of the image. The long poled flag aesthetically and metaphorically connects two celestial and terrestrial realms. In addition, the lax birds are depicted in white as an allusion to emancipated souls of the purified.  | Figure 5. Death of Shīrīn, illustration to Nizāmī’s Khamseh, Tabrīz, Turkmen’s school, 911 A.H. |

Not surprisingly though, color symbolism invigorates when collaborated with iconographic imagery. In the illustration, Imam Ali fights with dragon, the wavering blush pattern of the horse skin is roughly reiterated in the sole piece of cloud up in the sky, right above the Imam Alī’s figure. The imagery thus proclaims a divine sustain for Emīr. In another miniature (Figure 6) the uniform, golden color of flame is purposefully drawn up to the sky, to show that this particular divine, test fire will not burn the honest sīāvash. | Figure 6. Sīāvash passes the fire, Safavid Dynasty, Parliament library, 10th century |

2.3. Harmony and Balance

The beauty of Persian miniature is considerably derived from its overall balance and harmony, which in turn partially rests on color. The aesthetic demand for the color harmony, as much as the representational or naturalistic considerations are concerned, verifies the choice of color for details. The medieval Persian painters were masters of delivering such a grandeur task. For instance, according to art connoisseurs, the juxtaposition of colors, patterns and figures in Bihzād’s illuminations is so authentic and proficient that even a minor adjustment muddles the visual unity of intricate complexity. [7] In Figure 3, as one such a masterpiece, proportions of some complementary and contrasting colors are applied to create such a notable pictorial effect. As another example, in Figure 5, the recurrence of green, golden, white and blue flat surfaces ensures both symmetry and harmony. Since the surface of miniatures is fully covered with colors, part of the harmony serves to interlink different levels of the depicted scenario, a task which again relies on the genius employment of color and form. In Figure 1, the enclosed yard links to the outer space through Ardeshīr himself. The lower ground connects to the wall surface as continuation of the greeneries up to the yard surface. The upper ground is also joined to the blue sky by virtue of the tree trunks. In this way, no part of the illumination is left uncertain, suspended or separated from the rest of the scene.

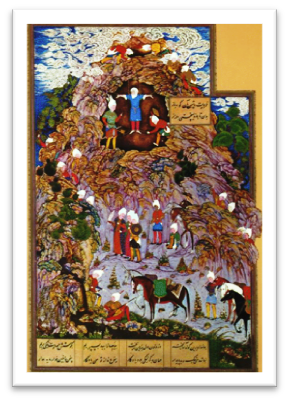

2.4. Accentuation

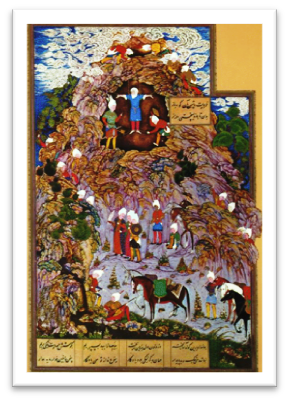

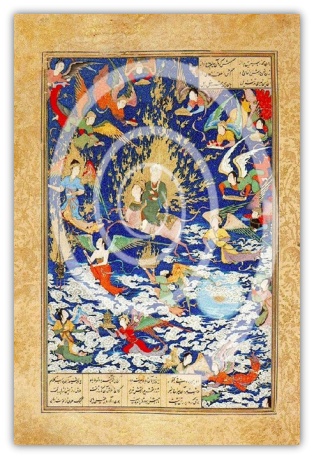

In Persian miniature every minute detail seems to be engrossed in the integrity of the whole image. Somehow colors are occasionally called upon to accentuate a phenomenon, event or character. In Figure 7, the big gloomy stain, with the glimmering lapis lazuli colored figure inside it at the top of an arduous mountain draws abrupt attention. The impassable cave is where the central theme of the illustration lays, the enchaining of ruthless Zahāk by hero Fereydūn. Likewise, in Figures 6 and 8, the large surface of golden flames makes it impossible to overlook the glowing innocent personage of Sīāvash and holy figure of Prophet (PBUH) respectively. | Figure 7. Fereydūn enchains Zahāk, illustration to Ferdawsī’s Book of Kings, by Sultan-Muhammad, Tabrīz, circa 940 A.H. |

To achieve the promised functionality, the artist exploits techniques other than merely putting a large amount of color on the surface. In the elaborate illumination of Josef and Zulaykhā (Figure 3), Bihzād’s intricate composition by no means undermines the surmounting context. Otherwise, the greenness of the Josef’s abstinence and redness of Zulaykhā’s love actuate the viewer pass the corridors and witness the contending sides at the very decisive moment. In this way, the diversity of hues and veracity of tones enthrall even today’s art critics, thus admiring Persian miniature as an inspiring state of art.

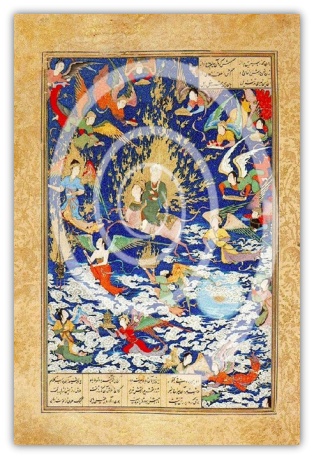

2.5. Evoking Motion

“Persian miniature involves movement from two dimensional expanse to three dimension space and from a panorama to another.” [8] Color triggers this transition. In exemplified illumination of ascension or Mi’rāj (Figure 8), the complementary tones of angelic attires and wings, contrasted to cold navy blue of background and interweaving white and gray of clouds prompts a sense of revolving motion. These features, alongside the influx direction of angels, underline the Prophet (PBUH), as the focal figure of the illumination. | Figure 8. Ascension of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), Frontispiece to Nizāmī’s Seven Icons of Khamseh copied for Shāh Thahmāsp, by Sultan-Muhammad, Tabrīz, 946-95 A.H. |

Aesthetically, color contrast promotes motion and vitality. The quintessential Figure 9, depicts the infantry and yeomanry in heavy dark colors, whereas battle ground and hillsides in vivid bright tones. The shimmering flux of these two motifs thus signifies the inconsistency of battle field. | Figure 9. Fight between Khusrow and Bahrām, illustration to Nizāmī’s Khamseh, Tabrīz, Turkmen’s school, 886 A.H. |

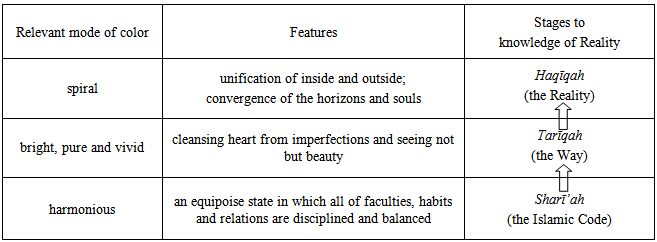

The encountered functionalities could be perceived as ramification of an integrated attitude. In fact color in Persian miniature proceeds, in a way or another, to manifest an occulted reality which lurks behind the aesthetical facade. This artistic manifestation of reality appealingly evokes knowledge of Reality (ma’rifat ul-Haq), the ultimate objective of the Islamic mysticism and theosophy. According to the Muslim sages, attaining felicity involves three stages: Sharī’ah (Islamic code), Tarīqah (the way) and Haqīqah (the Reality). Each of these is to be considered the means to or the shell of the next; and Haqīqah, being the innermost kernel, is the fruit of sulūk. Yet, in exactly the same way as the human being has three ingredients, body, self and reason, forming an indivisible whole of which they constitute inward and outward aspects, so is with the Sharī’ah, Tarīqah and Haqīqah. Acting in accordance with Sharī’ah leads man to an equipoise state in which all of his faculties, habits and relations are disciplined and balanced. Accordingly the inspired Muslim artist magnificently interprets and transmits this state to pleasant balanced designs and harmonious colors. Afterwards, the initiate (mobtadī) who has successfully confined his commanding self, steps in the path (tarīq), which unless covered, arriving at the station of truth is impossible. The purifying procedure results in cleansing heart from imperfections, as the devotee let the divine light shine his heart. There he can see and not see but beauty. This explicitly clarifies the artistic style of the Persian miniature, in which nothing resides in shade; instead everything appears in its utmost vigorous and vivified state.

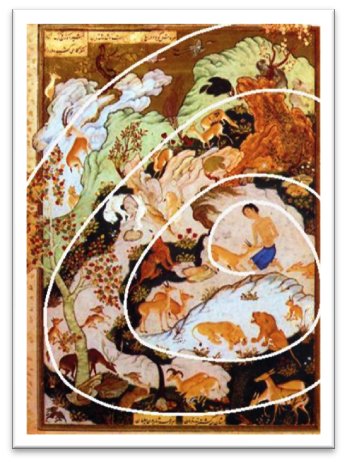

3. Spiral Structure

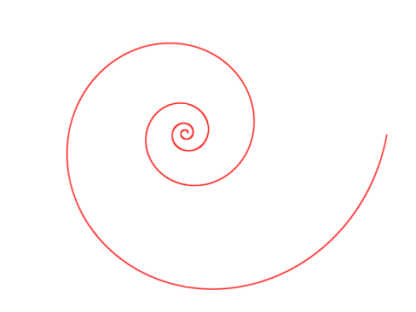

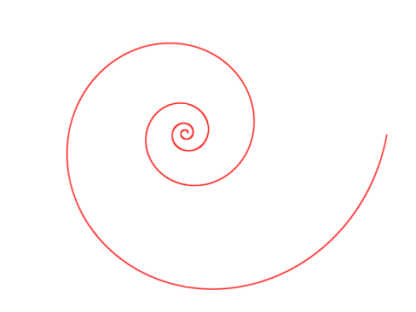

The jewel-like quality of the Persian miniature “seems to banish sadness-even when these fairytale scenes, on close inspection, reveal battles, massacres, and funeral processions.”[1] Eventually, after crossing divine frontiers, the veils rend asunder and the concealed manifests. Observing the occulted and perceiving the knowledge of reality is, as theosophists hold, a direct outcome of the wayfarer’s unification of inside and outside. The pictorial interpretation of this missionary expedition could be perceived in the implied spiral composition of numerous outstanding illustrations of the late Islamic middle ages. The “universal cosmic symbol” of spiral has a number of outstanding properties. The perpetually whirling curve, on the surface of paper, symbolically resembles approaching infinite realm. Indeed, to access such an ultimate destination, there is no choice other than limiting the unlimited. The potential simultaneous movement of spiral’s two ends seems to stop on the paper. Also “it both comes from and returns to its source; it is a continuum whose ends are opposite and yet the same; and it demonstrates the cycles of change within the continuum and the alternation of polarities within each cycle. It embodies the principles of expansion and contraction, through changes in velocity, and the potential for simultaneous movement in either direction towards its two extremities. On the spherical vortex these extremities, the center and periphery, flow into each other; essentially, they are interchangeable.” [3] The erudite Persian artist proficiently selects spiral structure, as the outline, to arrange his patterns and colors. The circular formation integrates the aforementioned color functionalities. It implements all those features in one single composition, from creating aesthetical effect of an incident to highlighting the central motif of the scene. Indeed, the whirling composition tours the viewer around the page and at the same time, detaching him from peripheral outskirts, guides the eyes to the center of spiral or focal point of the painting. This reminds an essential axiom in Islamic cosmology, tawhīd, according to which “everything in existence appears from one supreme principle and returns to it.” [9] The spiral structure, in principle, entails a simultaneous inward and outward movement, while the motion interminably goes on to infinity in both directions. As shown in Scheme 1, any arbitrary point (like a) concurrently lies inside and outside of the critical line, a resemblance of the inward and outward dimensions of actual entities. Moreover, “a” encounters two facets of exoteric and esoteric, alluding to the macro and micro cosmos (the universe and man’s consciousness). | Scheme 1. Spiral curve |

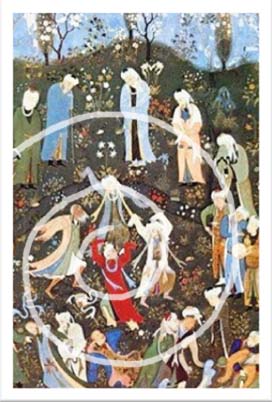

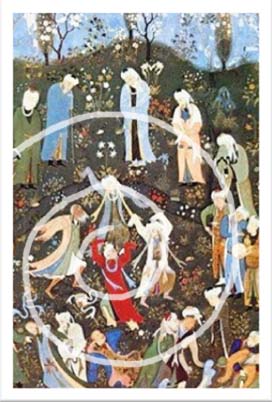

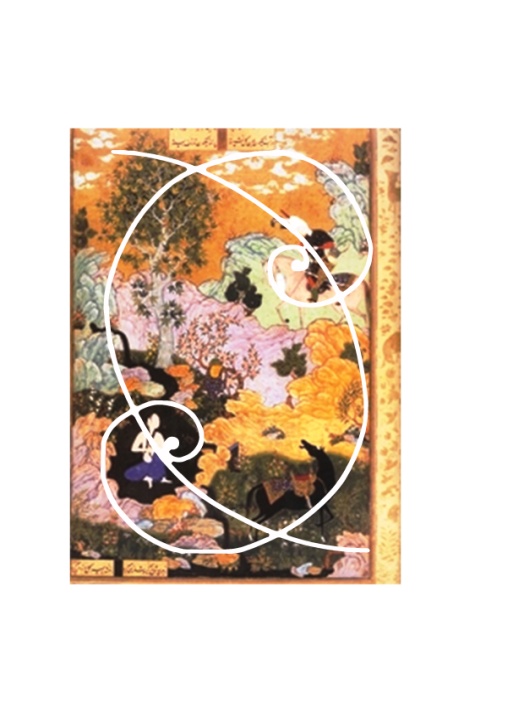

Due to extant chronicles, prominent Muslim artists such as Khājeh Abdul-Hay, Jonayd, Farhād, Bihzād, Agha Mīrak, Sultān Muhammad and Dervish Muhammad Sīāh-Ghalam had doubtlessly acquired some sort of spiritual states and virtues. Notably in some masterpieces of these celebrities, form and color collaboration in spiral composition endorses the artist’s profound religious inclinations. Bihzād’s Dancing Dervishes (Figure 10), Agha Mīrak’s Majnūn in Desert (Figure 2), Jonayd’s Fight of Humay and Humayun (Figure 11) and Sultan Muhammad’s Sultān Sanjar and Old Widow (Figure 4) are just a few instances of such brilliant illustrations. Another remarkable masterpiece of Sultan Muhammad is quite compelling (Figure 12). A close assessment of this miniature reveals not one, but two superimposed spirals, whose centers embrace protagonists of Nizāmī’s Khamseh, Khusrow and Shīrīn. The inspiring lyric of these two in-love characters and the contribution of feminine and masculine personas in the mystical union are proficiently conveyed in this illumination. The spiral vortex is intrinsically asymmetric; so to depict the steady and symmetrical state of ultimate union, Sultan Muhammad organizes his intricate motifs in two mirrored spiral structure. | Figure 10. Dancing dervishes, illustration to Hafiz’s Divān, attributed to Bihzād, Herāt, Timurid Dynasty, 895 A.H. |

| Figure 11. Fight of Humay and Humayun, illustration to Khaju of Kirman’s Divan, by Jonayd, 799 A.H. Museum of Britain, London |

| Figure 12. Khusrow watches bathing Shīrīn, illustration to Nizāmī’s Khamseh, by Sultan-Muhammad, Tabrīz, circa 918 A.H. |

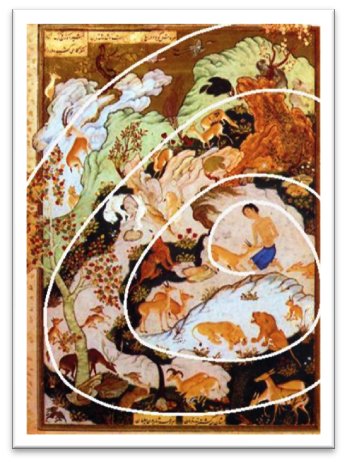

Summing up, unification of inside and outside, convergence of the horizons and souls and unity in plurality and plurality in unity, all manifest through color and form to soar the mind to the realm of unheard and unseen. Table 1 demonstrates the enlightening pilgrim to reality along with analogous structural integration of color features to the form of spiral.Table 1. Form vs. Content

|

| |

|

Melodious harmony of whirling color and form, along with entire attendant code of bejeweled visual symbols, qualifies Persian miniature as “endless pieces of weaving: instead of ensnaring the mind and dragging it into some imaginary world, they dissolve mental coagulations.” [6]

4. Conclusions

The color, form and structure in the medieval Persian miniature have connotations beyond certain decorative means. The harmonious mode of color corresponds to a status where all faculties reach a state of balance (sharī’ah). By going to the bright and vivid colors, the Persian artist conveys a sense of purity, close to what a Gnostic finds by the way of spiritual endeavor (tarīqah). The spiral marks the ultimate stage, where the soul unifies with its universal counterpart in the world of horizons (haqīqah). The sense of movement and unification articulated by the very structure of the spiral is a vehicle for giving life to the hidden vitality of the static and solid state of colors in the art work.

Notes

1. Italics are ours.2. illustration to Khāvarān Nāmeh, by Farhād, Shīrāz, 885 A.H.3. “Since any description of the Absolute must be limited, we are able to reveal it only by using symbols…The function of symbolism is to go beyond the “limitation of the fragment” and link the different “parts” of the whole, or alternatively the worlds in which these parts manifest: these worlds are successive windings of the spiral. Each symbol is a link on the same frequency with the world above, a vertical bridge between objects within the same “cosmic rhythm” on different planes of reality. On a flat spiral, each point of intersection of a symbol, traced through the respective worlds from the densest to the subtlest level of cosmic manifestation.”[3] 4. This indicates the limitless inward and outward aspects of the existence.5. See [10] which has referred to Persian treatises of medieval centuries, like those of Sīmī of Nishāpūr, Sādiqī Beg and Dost-Muhammad’s chronicle of painters.6. For further reading on symbolism and mystical interpretations of two superimposed spirals in other traditions refer to [3] and [11].

References

| [1] | Michael Barry, Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzād of Herāt (1465–1535), Spain: Flammarion, 2004. |

| [2] | Barry D. Wood, “A great symphony of pure form,” ARS Orientalis, vol. 30, p. 118, 2000. |

| [3] | Jill Purce, The Mystic Spiral, Journey of the Soul, London: Thames & Hudson, 1980. |

| [4] | Oleg Grabar, Formation of Islamic Art, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987, p. 233. |

| [5] | Gershom Scholem, “Color and their symbolism in Jewish tradition and mysticism,” in: Color Symbolism, ed. K. Ottman, Putnam: Spring Publication, 2005, p. 6. |

| [6] | Titus Burckhardt, “The void in Islamic art,” Studies in Comparative Religion, vol. 4, No. 2, 1970. |

| [7] | M.M. Ashrafi, Bihzād and Formation of Bukhara School, trans. N. Zandi, Tehran: Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance, 2003. |

| [8] | S.H. Nasr, “Alam ul-mithal and concept of space in Persian miniature,” Archeology and Art of Iran, vol. 1, 1968. |

| [9] | William Chittick, Science of the Cosmos, Science of the Soul, The Pertinence of Islamic Cosmology in the Modern World, Oxford: One World Publications, 2007, p. 74. |

| [10] | L. Binyon, J.V.S. Wilkinson and Basil Gray, Persian Miniature Painting, Oxford: Burlington House, 1933. |

| [11] | Geoff Ward, Spirals: The Pattern of Existence, Green Magic Pub., 2006. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML