Arthur Chun-Liang Chen

Department of Architecture, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, 43, Section 4, Keelung Road, Taipei 106, Taiwan

Correspondence to: Arthur Chun-Liang Chen, Department of Architecture, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, 43, Section 4, Keelung Road, Taipei 106, Taiwan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

This article attempts to introduce a significant private collection of Taiwan aboriginal artworks that was temporarily on display in the Taiwan National Museum of Art. “Culture” is human’s adaptation to the basic survival skills. It is both the process and the result of “humanization” through hard work and intelligence; hence, human’s primal urge to pursue “beauty” and “art” is inevitable. Indeed, “art” and “culture” coexist and complement each other in several ways. The abstract concept and implication of culture hides beneath the presence of art: we can interpret the significance of culture from a piece of artwork—art is a physical representation of culture. This article is based on more than one thousand pieces in the Taiwan aboriginal art collection of Mr. Chen Cheng Ching and explores the social and culture meaning behind the collection. Mr. Chen’s collection is number one in the Taiwanese Aboriginal art field, and its purpose is personal interest as well as public education.

Keywords:

Aboriginal, Taiwan, Artifacts, Art, Culture

Cite this paper: Arthur Chun-Liang Chen, The True Native Beauty of Taiwan - An Extensive Taiwanese Aboriginal Art Collection, International Journal of Arts, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 18-29. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20130302.02.

1. Introduction

What are aboriginal arts? Based on the Dictionary of Arts, it is any art which is not affected by European and Asian cultures, where the creative performances by the native tribes are generally known as aboriginal or primitive art.[1] According to this definition, all the pre-historic arts, creative performances by the African, Oceanic, American, and South Pacific natives are included. They are completely different from the Chinese and European Stone Age arts. Culture is both the process and the result of “humanization” through hard work and intelligence; hence, human’s primal urge to pursue “beauty” and “art” is inevitable. The abstract concept and implication of culture hides beneath the presence of art: we can interpret the significance of culture from a piece of artwork—art is a physical representation of culture. This article describes and explores the social and cultural meaning behind the over a thousand pieces in the Taiwanese aboriginal art collection of Mr. Chen Cheng Ching in the hope to raise public awareness about this art collection.

1.1. The Characteristics of Aboriginal Arts

Taiwanese aboriginal arts possess certain practicalities and functionalities. Their creations mostly represent religious, decorative, or social meanings, and the arts from different tribes all share some commonalities. Different from the traditional European and Asian arts, aboriginal arts use conceptualization as basis rather than observation. The creators of aboriginal arts rarely present things in a realistic way: when they depict humans or animals, they tend to pass on tribal or social beliefs rather than the physical representation of humans or animals. Reviewing countless Taiwanese aboriginal forms of art revealed that their expressions include gods or spirits of their ancestors. Their artistic creations are not self-perceptible attributes of subject, but the worship to perfection: a concept of worshiping their ancestors and a belief of surviving which leads the artists to create the power of life.[2] On the other hand, many aboriginal arts also showed the artists’ intention to express human biological structures.Taiwan’s native people either abandoned natural phenomena in their art works, or they would exaggerate natural phenomena to hint their meaning. Therefore, the argument could be made that the expression of the aboriginal arts is not related to our visual world; they are symbolism rather than naturalism.Aboriginal arts also play a unique role in social functions, as the arts had a place and role in ceremonies. As a result, collecting beautiful wood carved decorations in the Taiwan aboriginal society is seen as an activity of power.Aboriginal artists are often trained. They have to go through vigorous apprenticeship until their skills are at the pinnacle before they can start their art creation activities. This is why artists have power in some Taiwan aboriginal societies.

2. Review Subject

This article is based on the “Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan” published by the Taiwan National Museum of History and the over 1,420 artifacts collected by Mr. Cheng Ching Chen. “Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan” is a two book series, covered the nine tribes of Taiwanese natives at that time of publication and five categories of artifacts. Strictly speaking, such collection cannot fully represent the Aboriginal population in Taiwan by any means, but it is a showcase of multiculturalism in Taiwan. When Aboriginal artifacts are being presented as museum art pieces, their original functions, usages and meanings are often ignored. With the world widely increasing awareness of human rights, concerns of feminist and minority art steadily arise. Meanwhile, aboriginal art is considered not merely within the extent of anthropology and sociology, but taken as an example confronting with civilizations established on the basis of material evolution. In contrast with the drawbacks of modern civilizations, the purity and virtue of aboriginal art seems to offer a direct relationship between primitive life and its direct expression. This relationship manifests aboriginal art as evidence of innate creativity which contains characteristics such as expressiveness, structure and simplicity. These characteristics are such treasures which should be taken into account by [public and] contemporary art.[3]Huang, preface of " Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan"

2.1. The Origin of Taiwanese Aboriginal People and their Tribal Distribution

From the point of cultural characteristics and linguistics, the Taiwanese aboriginal people belong to a branch of Austronesian, who migrated from the South Sea Islands approximately 5,000 to 1,000 years ago. The Taiwanese aboriginal people were first called the “Shengfan,” meaning uneducated native. For that Toyotomi Hideyoshi [4] called Taiwan the Takasago Country or Takasago County, so it was later changed to the new name—Takasago Tribe. On October 25, 1945, in order to celebrate the retrocession of Taiwan, the Takasago Tribe assembled a tribute team to Taipei and made the mark of respect to the Taipei Forward Command Base. The editor of the Taiwan News (the former of the Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News), Dr. De Shi Huang thought the name Takasago Tribe had a strong Japanese feel, so he changed the name Takasago Tribe to “Mountain Compatriots.” Some people felt that the word "tribe" has an alienate feel and separates the mountain people and the Chinese people, therefore administratively they were all referred to as mountain compatriots.[5] In fact, only 60% of the mountain compatriots live in the mountains, 40% of them live on plains. For example, the Lanyu Yami Tribe lives close to the sea; the Taitung Puyuma Tribe lives in the Taitung Plain, and the Amis Tribe lives in the Taitung Valley. Later, the term “mountain compatriots” was considered inappropriate, so in 1994 it was officially changed to “Taiwanese Aborigines”.[6]The Aboriginal Peoples of Taiwan are the First Nations of Taiwan. Fourteen rich veins in Taiwan’s web of cultures are officially recognized: the Amis, Atayal. Bunun, Kavalan, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Saisiyat, Thao, Tsou, Yami (Tao), Truku, Sakizaya and Sediq.[7]

3. The Beauty of Taiwanese Aboriginal Arts

Taiwanese aboriginal people already established their unique art cultures centuries before the Spanish, Dutch, and Chinese arrived. Their existing cultures were not affected by China, India, and Arabic cultures. Taiwan is an isolated island with natural geographical barricades on all sides. With little to none transportation system, communication with the outside world was limited, which is why its culture could be maintained at the purest form. Taiwanese aboriginal people were artistically talented, and they left behind many stunningly spectacular artworks. These works of art took up an important position in the global aboriginal arts and are valued by people in the field of academic and art internationally.The art works of aboriginal people are mostly based on religion, decoration, and social functions. The same concepts can also be seen in the Taiwanese aboriginal art works. The range of their creation is very broad, including carving, weaving, pottery, decorative accessories, bamboo crafting, etc. But from the artistic point of view, their most characteristic performances come from their wood carving and weaving, which are the essence of Taiwanese aboriginal arts.

3.1. Wood Carving

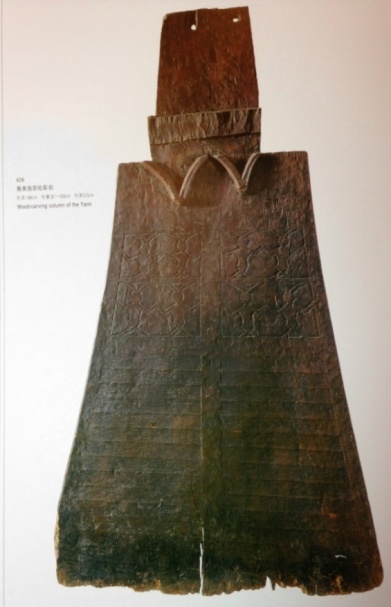

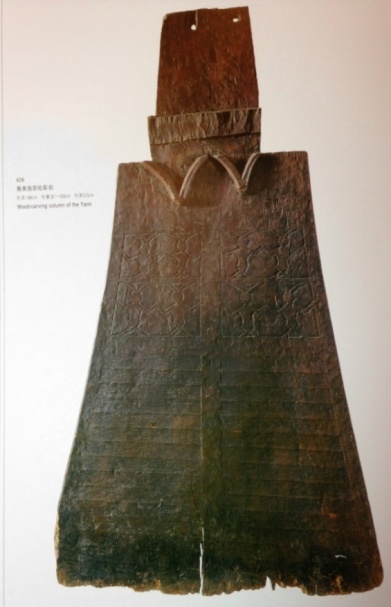

In all Taiwanese aboriginal tribes, the Paiwan Tribe in the south, the Yami Tribe in Lanyu and the Kamalan Tribe in the Lanyang Plain are most known for their wood carving arts; especially the Paiwan Tribe who is known as “the most artistic tribe.” This tribe is naturally talented and possesses fantasy and creativity. Feudalism fueled the arts development of the Paiwan tribe. Paiwan tribe has a feudalism structure similar to the Zhou Dynasty, where the lower ranked tribal members must pay taxes to tribal noblemen. The noblemen have economic privileges and live in beautiful houses, wear fancy clothes, use high quality ceramic ware, and have the privilege to carve wares.[8]Most of the Paiwan tribal carvings are in wood or stone. Their stone carving is more primitive and mysterious than wood carving. Taiwu, Laiyi, and Wutai of the Pingtung County were the centers of carving arts. Carvers in Jiaxin Village in Taiwu Township, situated deep in the mountains with little or no incoming traffic, maintain their primitive style, and high quality carvings are often seen.[8]Wood carvings mostly come from the houses of the noblemen, with items as small as smoke pipes, spoons, cups, combs, wooden boxes, fortune telling box, dolls, sawing boards, gun powder holders, knifes, spears, wooden shields, staffs, bells, etc. Although the patterns they use are limited, the varieties are limitless. Even a small knife can reflect the superb carving skills of the artists. The most common patterns that Paiwan tribe carves include human figure and head, snake, deer patterns; geometry shapes are mostly used as the border decoration, which are derived from the human head patterns and the snake patterns.Paiwan tribe practices worshiping ancestors, and they use human patterns to represent their ancestors. Other than representing their ancestors with a human head, it may also be related to their headhunting ritual (Fig. 1). They use the snake pattern because they believe the venomous viperidae is their ancestor, and they have a reverence toward it (Fig. 2). They use the deer pattern because it is related to their daily lives. As mountain deer is abundant in the mountains and they can be seen anywhere, it is normal to adopt them into their decorative patterns.  | Figure 1. Wood-carving column of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 52.) |

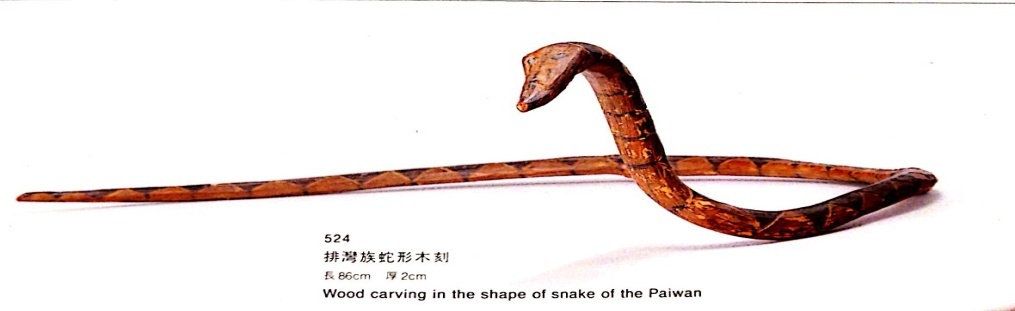

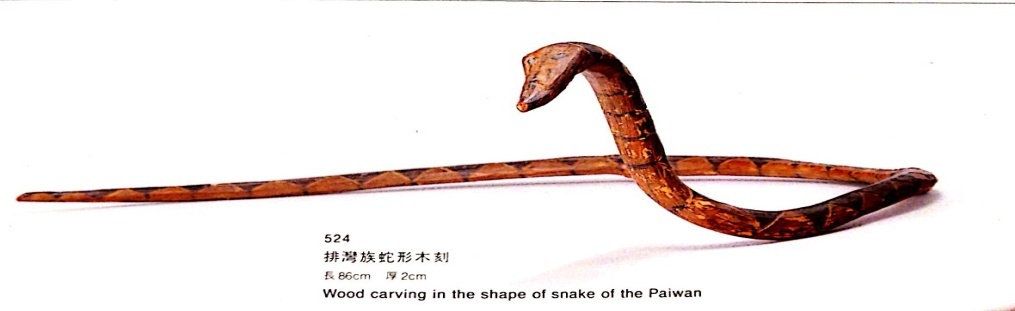

| Figure 2. Wood carving in the shape of snake of the Paiwan. ( Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan.Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 143) |

Most of the Paiwan human figure pattern carvings are standardized, with Rukai style totem, round head, long nose, small eyes, hands raising to almost chest height or shoulder height, all five fingers are the same length and the toes facing outward, short and thick bent leg (Fig. 3). They also use genitals to distinguish between the sexes, so human genitals are made very obvious, common with the characteristic of southern island tribal arts (Fig. 4, 5). | Figure 3. Wood carving ancestor of the Rukai. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 32) |

| Figure 4. Wood carving column of the Rukai. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 34.) |

| Figure 5. Wood carving column of Paiwan. (Source: Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 60.) |

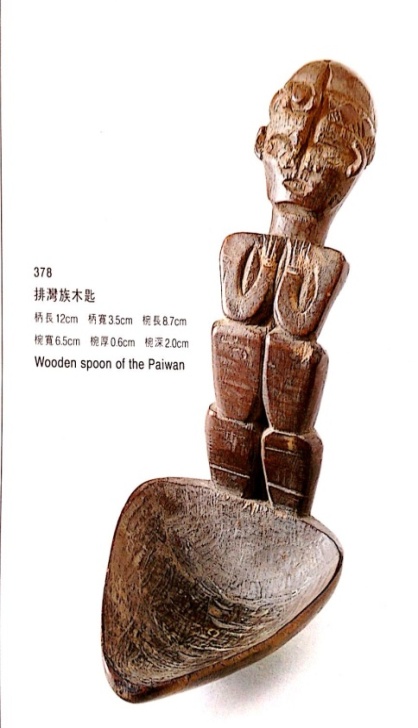

As previously mentioned, the Paiwan human pattern carvings all have their toes facing outward, like children’s depiction. This is because the early carving was mostly flat, which is different from the African Native’sthree-dimensional carving. There were few three-dimensional carvings, but they had already been influenced by the Chinese. These rare three-dimensional carvings were most in the form of human figures (Fig. 6), cigarette-holders (Fig. 7), and spoons (Fig. 8). They are symbolic and decorative - both are the characteristics of Paiwan tribal wood carvings. | Figure 6. Wooden idol of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 136.) |

| Figure 7. Cigarette-holder of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 97.) |

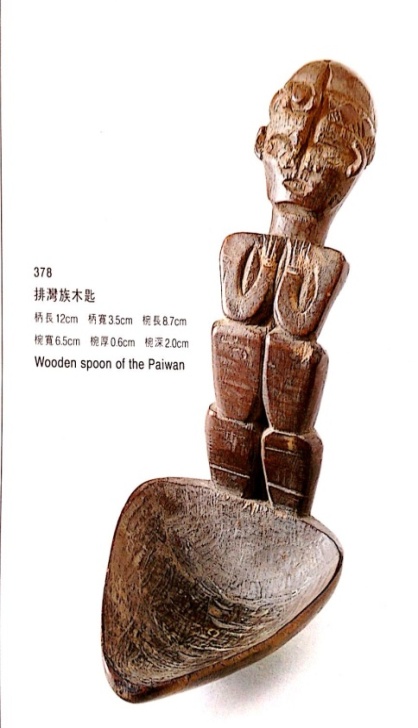

| Figure 8. Wooden spoon of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 87.) |

The Yami Tribe is also excellent at carving, especially in precious metals like gold or silver. Most of their carvings include geometric carvings on wooden boats (Fig. 9), house pillars, wall panels (Fig. 10), boat decorations (Fig. 11), short knives (Fig. 12), fishing needle boxes (Fig. 13), etc. The Lanyu Wooden Boat is a classic aboriginal artwork. The Yami Tribe likes to use concentric patterns, saw-tooth patterns, zigzag patterns, diamond patterns, and human portrait pattern with red, white, and black colors. The patterns and colors fully cover the body of a boat, which showcases the tribe’s optimism.  | Figure 9. Boat of the Yami. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 200.) |

| Figure 10. Wood-carving column of the Yami. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 186.) |

| Figure 11. Stick for ceremony of the Yami. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 202.) |

| Figure 12. Knife for driving out evil (Yami). (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 204.) |

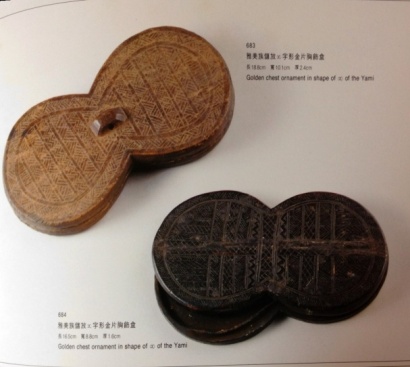

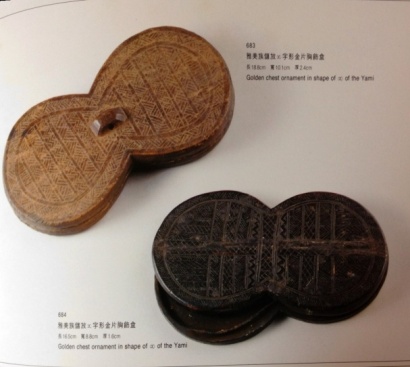

| Figure 13. Golden chest ornament in shape of the infinity sign (Yami). (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 217.) |

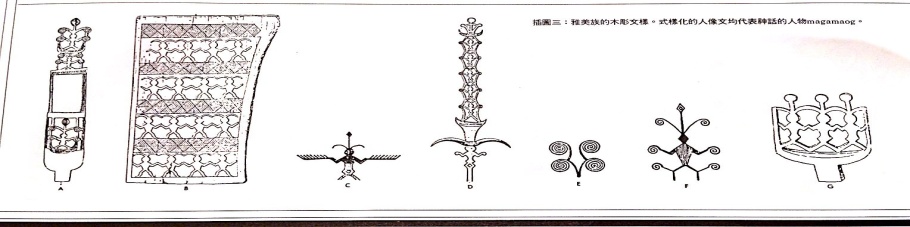

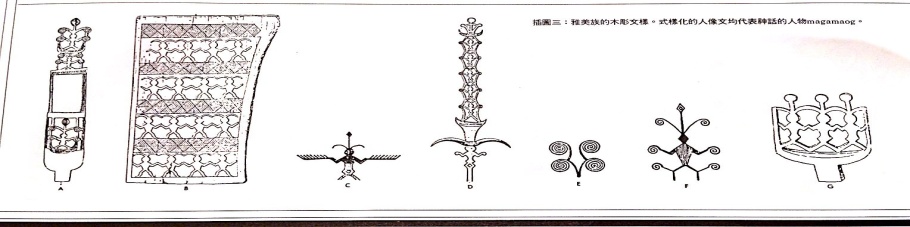

The goddess of the Yami Tribe and their standardized human pattern are called “Magamaog” (Fig. 14), representing the fable character who taught the Yami people how to build boats and to farm.[9] Yami people’s red paint is made by soil; white paint is made with limestone; and black paint is made by charcoal; together they show a simple and unsophisticated feeling which oil paints or ceramic paints cannot express. | Figure 14. Representing the fable character Magamaog. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 15.) |

The Yami Tribe has been protected by ocean since ancient time and they were never invaded or influenced by other people, so their native culture was preserved, and Lanyu has always attracted anthropologists and artists. The carvings of the Yami tribe are simple in techniques with primitive lines. The carvings of the Taiwanese native people are direct and honest and can continue to evoke a somewhat frightening mysterious feeling in viewers.

3.2. Weaving

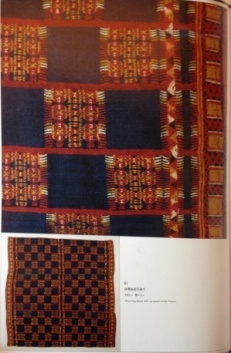

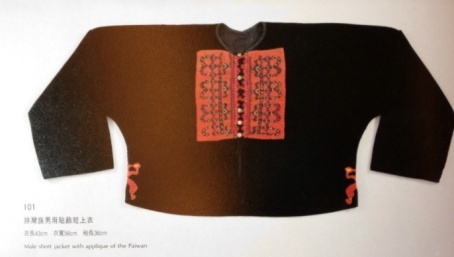

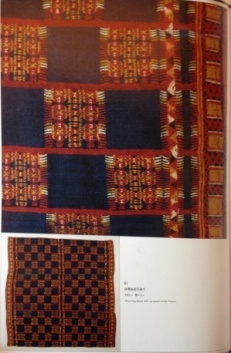

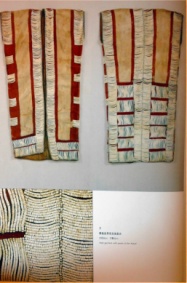

The traditional Taiwanese aboriginal custom is that men hunt and women weave and do embroidery. The embroidery skills of the Taiwanese aborigines are advanced. The most famous embroidery comes from the Paiwan Tribe, the Pingpu Tribe of Fengyuan in Taichung County, and the Atayal Tribe in the north of the island. The techniques can be further categorized into clip weaving and knitting.[10]The Paiwan embroidery uses linen as the base with the wool purchased from Chinese. They unravel the wool then re-roll them into color strings, and use them during weaving to make patterns. Sometimes they will add decorative fabric pieces and pearls on top of the clip weave for the noblemen’s clothes (Fig. 15). The Paiwan weave patterns that can be magnificent and complex, using human head and human figure patterns onto linen and using geometric pattern on the rims as supplementary, with bright colors of orange, yellow, and green (Fig. 16). The colors are always bright and balanced, the weaving skill is experienced and exquisite, and their fish scale weaving pattern is one of the best in clip weaving.The patterns used by the Paiwan tribe are said to represent their inner world. For example, they worship their human-head and snake-bodied god and ancestors, and use these patterns in woven clothes. Although the themes are similar, no two woven pieces of clothing are alike. Sometimes a completely non-related pattern on the Paiwan tribe embroidery is found, and they are the results of the interlaced latitude and longitude lines, which created this irregular pattern. This inconsistency is not made by purpose but reveals the limit in the functions of the embroidery.  | Figure 15. Male short jacket with appliqué and glass beads of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 106.) |

| Figure 16. Mourning shawl with jacquard of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 72.) |

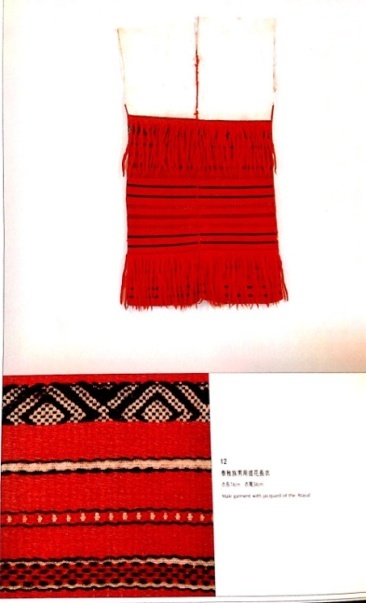

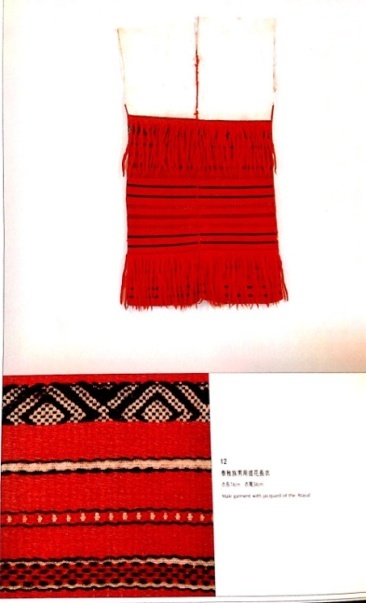

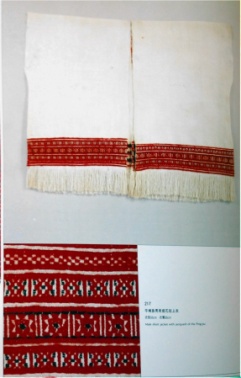

The biggest difference between the Atayal clip weaving and the Paiwan clip weaving is the patterns. Atayal Tribe does not use realistic human pattern and head patterns, but something more abstract such as variety of geometry patterns. Whether it is in the curves, lines or triangles pattern, diamond pattern, or square pattern, the weave is simple and yet contemporary. Red, black, and blue are the most popular colors to Atayal people (Fig. 17). | Figure 17. Male garment with jacquard of the Atayal. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 36.) |

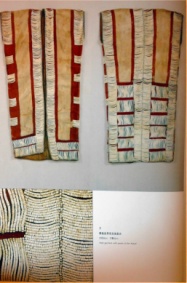

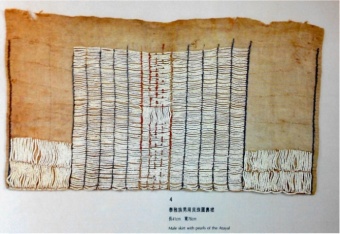

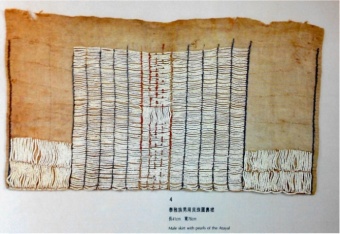

Pearl knitting is popular among the Paiwan Tribe, the Rukai Tribe, and Atayal Tribe. They all use different materials and techniques to express their styles of pear knitting artworks. The Atayal people cut the shells they purchased from Chinese into thin cylinder stripes, then mill them into pearl shapes, and string them with strings, and knit the whole strings onto the clothes as decorations. Many Atayal tribal clothes have this kind of pearl strings as trim. Another type of special pearl clothes (Fig. 18) or pearl skirts (Fig. 19) have strings of different sizes of pearls and arrange them horizontally or vertically to create interesting patterns. Due to the special materials, the Atayal tribal clothes are treasured by everybody, and museums around the world all eager to purchase them for display. In addition, the “Jinchai long clothes” of the Atayal tribe is another distinctive artwork (Fig. 20). | Figure 18. Male garment with pearls of the Atayal. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 28.) |

| Figure 19. Male skirt with pearls of the Atayal. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 29.) |

| Figure 20. Male garment with bells of the Atayal. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 31.) |

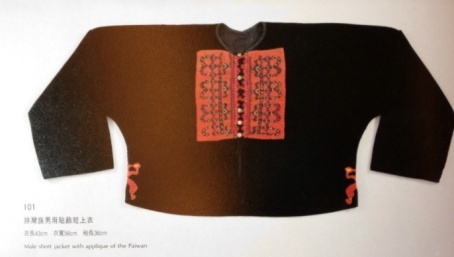

The pearl knitting from the Paiwan and Rukai tribe contains small orange, yellow, and green glass material—put together into patterns on the clothes (Fig. 21). They mostly use human patterns in their knitting and small, opaque, and matte glass balls.This kind of pearl knitting is very valuable, and they can be seen in every tribal locations of the Paiwan tribe, with higher concentration in the northwestern area. The Paiwan, Bunun, Tsou, and Pingpu tribe all excel in their embroidery skills. Each tribe uses different patterns in its weaving, some are geometric and some are more realistic.The embroidery of the Rukai tribe stands out the most. Many different styles of embroidery such as cross knitting, straight knitting, satin knitting, and chain knitting, are displayed brilliantly in diamond patterns or symmetric radiation pattern (Fig. 22). The patching knitting is mainly used by the Paiwan tribe. They love to use red color as the base and patch with different color patterns; or they would patch red patterns onto black clothes (Fig. 23). The patch knitting is a creative artwork. It can be separated into layered pattern, triangle pattern, and leaves pattern.  | Figure 21. Male short jacket with glass beads of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 107.) |

| Figure 22. Male short jacket with embroidery of the Rukai. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 64.) |

| Figure 23. Male short jacket with appliqué of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 108.) |

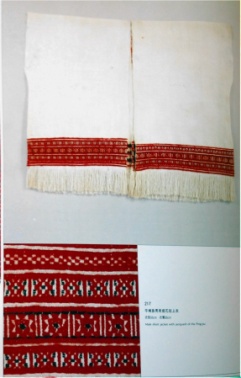

The Bazai tribe that used to live in the central Taiwan was a branch of the Pingpu tribe. They have already been localized with the Chinese, but they have left behind their excellent embroidery techniques.[11] The common patterns they used are stripe pattern, zigzag pattern, diamond pattern, triangle pattern, and black pattern; from their diamond patterns, we can see the influence from their frequent contacts with the Chinese. Red, blue, and black are the three most common colors; they sometimes also weaved the golden wheat into their pattern, which were very characteristic and priceless (Figure 24, 25). | Figure 24. Male short jacket with jacquard of the Ping-pu.(Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 180.) |

| Figure 25. Male short jacket with jacquard of the Ping-pu. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 182.) |

Based on the techniques, the Jiaxin Village of the Taiwu Township is the best in wooden carving, and the Gulo Village of the Laiyi Township is the best in embroidery. The Taiwanese indigenous tribes also have beautiful artworks in pottery and bamboo crafting.

3.3. Pottery

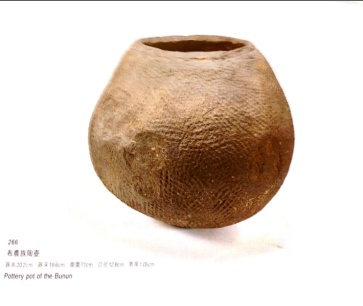

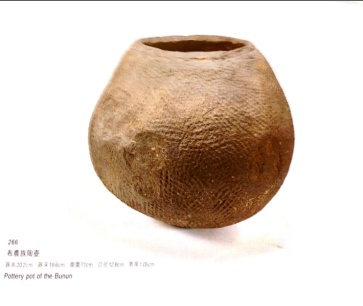

The Taiwanese native tribes have been using clay pots since the ancient times, but the technique has been lost. The tribes that are still using clay pots are the Paiwan, Rukai, Yami, Atayal, Bunun, and Tsou tribe. The only tribes that are still passing down the pottery making techniques are the Atayal, Yami, Bunun, and the Tsou tribe. They use hand made or mold molding methods, which are very different from the African and the American Natives.The patterns on the pottery of the Bunun tribe resemble the fishnet, which has a dense primitive color to it, and draws connection to the Jomon pottery of the Stone Age (Fig. 26). | Figure 26. Pottery pot of the Bunun. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 28.) |

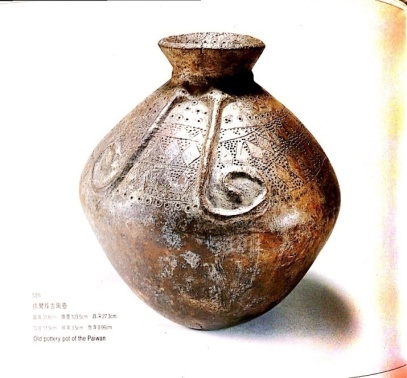

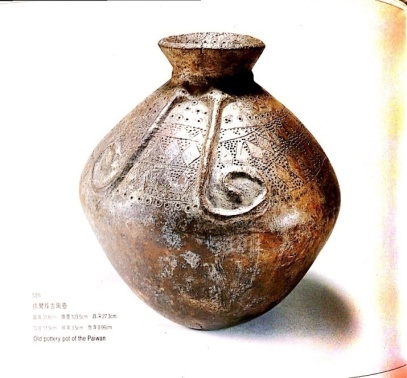

The pottery technique of the Paiwan tribe has been lost. All what is left are the clay pots that were passed down from generation to generation. Each clay pot belongs to a different type, according to their shape and pattern; there are also gender differences.The Paiwan tribe believes that the clay pots have supernatural powers, so they have a deep respect to their pots and a strong superstitious concept. Since they are rare, the value of these pots is extremely high. Noble families treat them as heirloom. The value of a clay pot depends on its pattern. The most valuable pottery pot is the snake pattern. There are many ways to show the snake patterns, but the two most widely used methods are to form the snake pattern during the unfired green-ware stage and apply the whole snake onto a pot (Fig. 27). | Figure 27. Old pottery pot of Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 144.) |

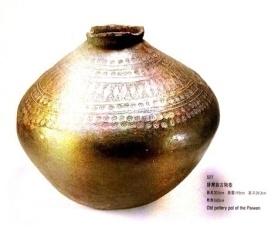

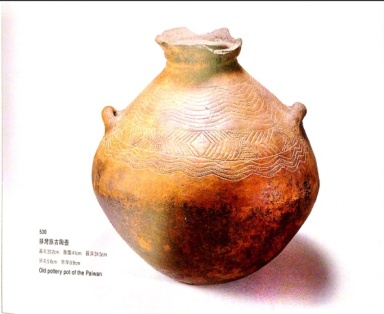

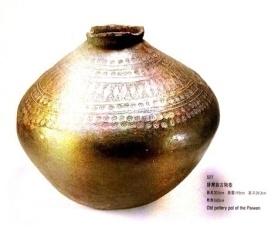

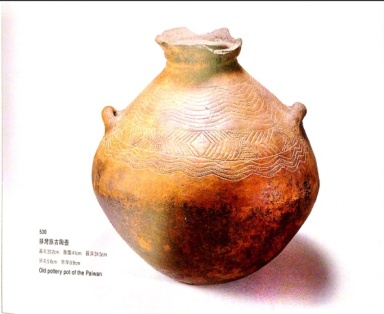

The second method is to carve the snake pattern onto the porcelain pot, or transform the snake into one or two circles of geometric shapes, or diamond shapes, triangular shapes, and diagonal shapes (Fig. 28, 29). | Figure 28. Pottery pot of Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 145.) |

| Figure 29. Pottery pot of Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 146.) |

A point worth noticing is that the pots representing the noble class contain snake patterns, or sun patterns, and there are no human patterns or head patterns. But the human figure and head patterns actually hold more noble meanings than the snake patterns, and why there are no human patterns is an unsolved mystery.The Atayal tribe also makes clay pots, and among those, the ceremonial pots are the most valuable. The ceremonial pots are used as offerings to the gods. Due to their rarity, they are most treasured.

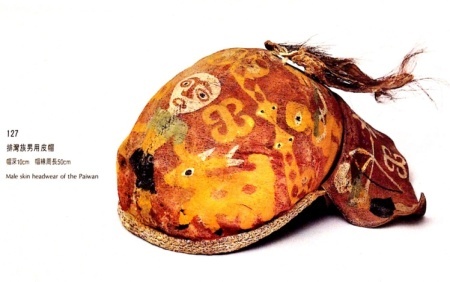

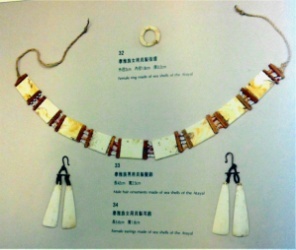

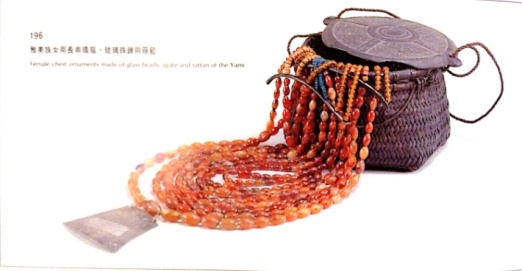

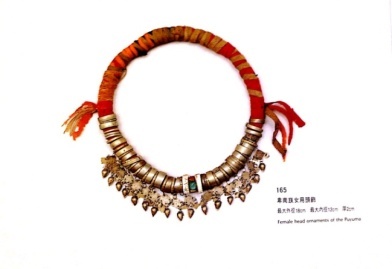

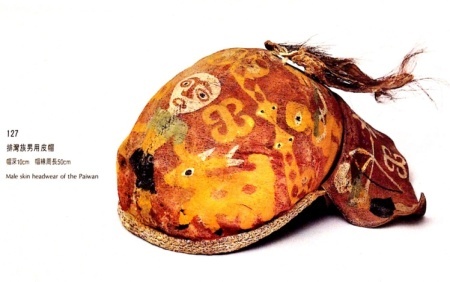

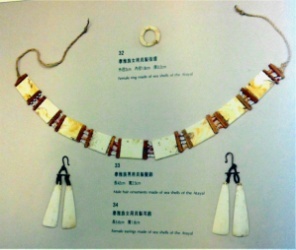

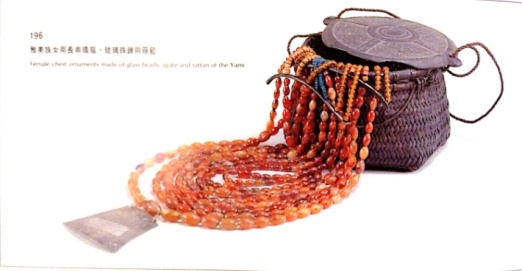

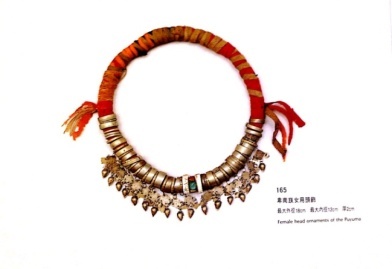

3.4. Decorative Accessories

The Taiwanese indigenous people’s accessories can be categorized into six parts of the body—head, ears, neck, shoulder, hands, and feet. Some of these accessories can be seen across different tribes, but some are used only in particular tribes, such as the shoulder pouch for the Paiwan tribe. Some are for both men and women, and some are not; for example, the cigarette pouch for the men and the chest accessories for the women. The social status of the bearer is strictly limited and cannot be ignored.The material of the accessories is also different from what we have seen, such as the animal teeth (Fig. 30), animal skins (Fig. 31), seashells (Fig. 32), and glass balls. Agates, Qianlong beads, and tassels are also used. The animal teeth and the skins are obtained from animals in the mountains, the shells are from the seas; but the sources for the glass balls are more unique, they probably came from Middle East or southern seas (Fig. 33). The agates (Fig. 34), Qianlong beads and the tassels (Fig. 35) are obtained from trading with the Chinese. Because their own decorative accessories are limited in styles and materials, they would treat these new materials from trading as treasures. Due to the fact that transportation is more convenient nowadays, they have more contacts with the outside world, and they can easily get more material, but they are as a result also losing their primitive orientation in the creation of artworks. | Figure 30. Badge of headwear of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 121.) |

| Figure 31. Male animal skin headwear of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 123.) |

| Figure 32. Accessories made of seashells of the Atayal. ( Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 52.) |

| Figure 33. Female glass beaded necklace of the Paiwan. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 143.) |

| Figure 34. Female chest ornaments made of glass beads, agate and rattan of the Yami. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 172.) |

| Figure 35. Female head ornament of the Puyuma. (Source: Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. 153.) |

3.5. Bamboo Crafts

The most common item of all the Taiwanese aboriginal people is the woven basket; every tribe uses them. The small ones are used in kitchen to prepare food, the big ones are used for storage and transportation. Women also use their weaving techniques to showcase their sense of beauty and superb crafting skills.The materials of the weaving are mostly bamboo or vine. The styles of their weaving vary, but they can be divided into two main groups: the weaving method and the spiral weaving method. All other methods and styles came from these two methods, and each tribe also has their own variations to reflect their characteristics.Bamboo is best for weaving, and the most common style is the diagonal weaving as the patterns are straight and in squares. Vine is used in the spiral weaving methods; since vines are less abundant, spiral weaving techniques are rarely seen.

4. Conclusions

“The development and continuation of these wonderful [aboriginal] cultures are, under the threat of the rapid industrialization and social change, on the edge of a total disappearance. For the purpose of cherishing the aboriginal culture in Taiwan, realizing the [importance] of promoting this culture[3]," I feel compelled to introduce Mr. Chen’s collection to the widest possible audience. The Taiwanese aboriginal tribal art maintained its original southern island culture form because it was uninfluenced by the three major cultures of Asia for a long time. Not only it is a treasured culture for all anthropologists, but also a unique jewel that is originated from Taiwan and can be offered to the world. These artworks not only belong to Taiwan, but to the world. It is the most important part of the Taiwanese art history, and as such, should be cherished.

References

| [1] | Myers, Bernard S. McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Art. London. McGraw-Hill Book Company Ltd., 1969. |

| [2] | Wong, Hao Shang. Tribal Crafts and Culture Styles. 2006. Retrieved from<http://web2.nmns.edu.tw/PubLib/NewsLetter/95/218/2.pdf>. |

| [3] | Aboriginal Arts in Taiwan. Taipei: Taiwan National Museum of History, 1997. |

| [4] | Government Information Office. A Brief History of Taiwan: European Occupation of Taiwan and Confrontation between Holland in the South and Spain in the North. |

| [5] | Segawa, Kokichi. Apparel of Taiwan Takasago Tribe. Tokyo: Shoto Museum of Art, 1983. |

| [6] | Chen, Qi Lu. Material Culture of the Formosan Aborigines. Taipei: National Taiwan Museum, 1981. |

| [7] | "Taiwanese Aborigines." Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. 2011. Retrieved from.<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiwanese_aborigines>. |

| [8] | Chen, Qi Lu. Wood Carving Catalog of Taiwan Paiwan Tribe. Taipei: National Taiwan University, 1978. |

| [9] | Chen, Robert (Zheng Xiong). Symbol and Culture. Eastern Academic Thesis: 36th. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1990. |

| [10] | Chen, Robert (Zheng Xiong). Taiwan Aboriginal Apparel. The 6th International Apparel Academic Thesis. 1986. |

| [11] | Chen, Robert (Zheng Xiong). Carved on Life: The Native Totem. Furong Fung: 11 (1991). |

| [12] | Chen, Robert (Zheng Xiong). A Close Look to Taiwan Aboriginal Artifacts. Independence Evening Post. 1989. |

| [13] | Chen, Shali. Taiwan Aboriginal Apparel Culture. Taiwan: Nantian Books, 1998. |

| [14] | Segawa, Kokichi, Taiwan Aboriginal Apparel. Japan: Tenri University Sankokan Museum, 1966. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML