-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Arts

p-ISSN: 2168-4995 e-ISSN: 2168-5002

2012; 2(5): 31-38

doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20120205.01

An Analysis of Gender Displays in Selected Children Picture Books in Kenya

Philomena N. Mathuvi 1, Anthony M. Ireri 2, Daniel M. Mukuni 3, Amos M. Njagi 2, Njagi I. Karugu 4

1Department of Kiswahili, Kenyatta University, Kenyatta University, P.O. Box 43844, 00100,Nairobi

2Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, P.O. Box 43844, 00100,Nairobi, Kenya

3Department of English & Linguistics, Kenyatta University, P.O. Box 43844, 00100,Nairobi, Kenya

4Department of Education, Chuka University College, P.O. Box 109-60400, Chuka, Kenya

Correspondence to: Philomena N. Mathuvi , Department of Kiswahili, Kenyatta University, Kenyatta University, P.O. Box 43844, 00100,Nairobi.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Children’s books are an early source of gender role stereotypes. Gender displays in such books can be read or interpreted as a social problem in any education system. The study aimed at identifying common gender displays in 40 children picture books used as supplementary English texts for classes 1 to 3 in Kenya published between 2005 and 2010. Five forms of gender display were evaluated based on Ervin Goffman’s model of decoding gender displays and visual sexism. Through content analysis, mean stereotyping scores for each behavioural category were computed and the overall score for each year determined. Findings indicate that the behaviour of females is significantly different from that of males in the selected books. Both positive and negative images about females have been given although the pattern changes from year to year. Suggestions for practice and further research are given.

Keywords: Gender Studies, Ervin Goffman, Children Picture Books, Kenya

Cite this paper: Philomena N. Mathuvi , Anthony M. Ireri , Daniel M. Mukuni , Amos M. Njagi , Njagi I. Karugu , "An Analysis of Gender Displays in Selected Children Picture Books in Kenya", International Journal of Arts, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 31-38. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20120205.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- When a child is born, one of the first questions mothers encounter is whether it is a boy or a girl. Different people even behave differently to a newborn depending on its gender. Thus from infancy we are exposed to community portrayals of how one should behave with other people. It is, therefore, not surprising that roles associated with gender are among the first ones that children learn in life. Gender development actually comprises a critical part of learning experiences of young children. Since books contribute greatly to the learning experiences of young people, they equally contribute to their gender identity development. In this paper, we review various theoretical perspectives on gender development, effects of books on gender development, common motifs of gender portrayal in literature, gender stereotypes in children’s literature and then report on a study evaluating gender displays in children books used in Kenya.

2.1. Theoretical Perspectives on Gender Roles

- Different theories address when and how children begin learning about gender-appropriate behaviour and activities. Below is an overview of some theoretical perspectives:According to Lawrence Kohlberg[1] full understanding of gender develops gradually in three steps: Gender labelling (by 2 -3years) when children understand that they are either boys or girls and naming themselves accordingly; gender stability (during preschool years) when children begin understanding that boys become men and girls become women; and gender constancy (4-7 years) when most children understand that maleness and femaleness do not change over situations and personal wishes. The theory posits that gender serves to organize many perceptions, attitudes, values and behaviour. According to Kohlberg, children begin learning about gender roles after they have mastered gender constancy. Research generally supports this prediction[2] but Ruble and others[3] argue that children start learning gender-typical behaviour as soon as they master gender stability and this understanding becomes flexible with time. The gender-schema theory explains how children acquire gender roles by stating that children want to learn more about an activity only after first deciding whether it is masculine or feminine. Thus, when children know their gender, they pay selective attention primarily to experiences and events that are gender appropriate[4]. Some studies support this pattern[5].Under the framework of social cognitive theory, it is assumed that children learn gender roles by watching the world around them and learning the outcomes of different actions. Thus the actions of parents, teachers, siblings and peers shape appropriate gender roles in children[6]. In this perspective, children learn what their culture considers appropriate for males and females by simply watching how adults and peers interact. Under this theory, the development of gender role identity is shaped by the shared beliefs of society[7].Evolutionary developmental psychology informs us that different roles like providing important resources for young ones and involvement in child rearing caused different traits and behaviours to evolve for men and women[8]. The biological basis for gender-role learning is supported by studies which show strong preference for sex-typical toys and activities between pairs of identical and fraternal twins[9]. The perspective is also supported by research involving females exposed to male hormones during prenatal development[10].As children learn the gender roles, they also pick beliefs and images-stereotypes- about males and females from their social environment. These stereotypes influence differences in our expectations for males and females regarding their behaviour and feelings[11]. They also influence our response to other people’s behaviour and the inferences we make about behaviour and personality[7]. Research indicates that children learn gender stereotypes early in life and that gender stereotyping increases with age. For example, in one study 18-month-olds exhibited gender differences in how they looked at gender-stereotyped toys. Girls looked longer at pictures of dolls than pictures of trucks while boys looked longer at pictures of trucks[12]. By 4 years of age, children’s knowledge of gender stereotypes is extensive and they begin to learn about behaviours as well as traits that are stereotypically masculine or feminine[13]. For example, a 2005 study found that preschoolers believed that boys are more often aggressive physically but girls tend to be aggressive verbally[14]. 5-year-olds believe that boys are strong and dominant and girls are emotional and gentle[15]. Beyond preschool years, children learn more about stereotypes, become more flexible regarding gender stereotypes[16] and learn differences in the gender stereotypes[15].The theories on gender roles development are vast and we did not intend to exhaust reviewing all of them in this paper. However, it is apparent from the foregoing review that by the time children learn to read, they have acquired gender lenses through which they try to evaluate and understand social experiences. It is expected that children refine these lenses from the books they read.

2.2. Effects of Books on Gender Development

- In the process of socialization, societal values are transmitted from one generation to the next. As noted by Arbuthnot[17], books are often the primary source for the presentation of societal values from one generation of readers to the next and for gender socialization[18]. Consequently, children’s books serve as a socializing tool to transmit values to the young. These books are a strong purveyor of gender role stereotypes.Temple and colleagues[19] describe three types of picture books: wordless books (where the reliance is totally on pictures to tell the story); picture storybooks (where text and illustrations combine to tell the story); and illustrated books (which rely mainly on the text, supported by illustrations to tell the story). The unique feature of picture storybooks is that the text and story do not merely reflect each other. The text and illustrations amplify each other to tell a story that goes beyond what one reads. Stephens[20] suggests that ideologically, picture books belong firmly within the domain of cultural practices which exist for the purpose of socializing their target audience. Illustrated books particularly have a significant impact on gender development[21]. It is argued that the power of illustrated books lies in their use of visual images as nonverbal symbols[22].Research has affirmed that gender stereotyping in children’s books is influential on children’s identity development. According to Easley[23] the development of preschoolers’ gender identities often occurs concurrently with their desire to repeatedly view their favourite picture books. Other researchers highlight the detrimental effects of negative gender portrayals in children’s books on their identity, self-esteem, and perception of gender roles[21]. Exposure to sex-stereotyped books contributes to an increase in sex-typed play behaviour[24]. Other researchers posit that picture books offer children a resource through which they discover worlds beyond their own life-space. Picture books help children to learn about the lives of those who may be quite different from themselves[25]. Thus from reading picture books, children may adjust their existing knowledge about their developing gender identity. Thus the way socialization experiences are written exerts a positive or negative influence on the construction of gender role identities and stereotypes. The implication from the foregoing is that the books that educators and parents select for their children’s learning and recreation have an impact beyond the reading experience. There is a need to be particularly conscious about traditional gender stereotyping present in the reading materials that children are exposed to.Early children books emphasized the traditional role of the active male and the passive female. A commonly cited study[26] sought to find out if gender differences existed in characters and the representation of character roles in 18 Caldecott Award medal books. The study revealed that character differences described women as passive and immobile versus males as leaders, independent, and active. Males had higher occupation roles than females and overall males appeared 11 times more often than females in the central role, as the main character or even in the title. These books were argued to portray girls as second to boys in all aspects of life[21].It is interesting to note that the increase in the global steps towards equity between men and women has not been matched by increase in equal portrayal of men and women in literature. For example Crabb and Bielwaski[27] found that household artefacts were still most often used by females in children’s picture books and that females’ use of these artefacts failed to reduce over time. Other researchers report an increase in female representation as main characters in proportion to male characters and that authors were aware of the need for positive images for girls and boys[21] However, it was noted that women tended to assume non-traditional characteristics when in a central role and reverted to traditional stereotypes when not in a central role[28]. As a way of enhancing literacy skills development, children in primary schools are expected to read recommended texts. Most of the class readers are supplementary texts that are not tested in the national examinations. Mostly, such texts are by African writers though some classic texts from Europe are at times included to enrich the literary experience of the students. In their reading of the selected books, the children are expected to enjoy their reading as well as demonstrate awareness of the society in which they live[29]. However, it is not clear whether such books present gender stereotypes to the children. In addition, most of the available studies on the portraiture of gender in children literature have been conducted outside Kenya and few of those conducted in Kenya focus on children literature meant for classes 1 to 3. Further, current studies on the portraiture of female characters have mostly focused on characterization and few have been conducted on how children perceive characters in the picture books. Out of this, little is known about the kind of stereotypes we expose our children to through the selected literature. To contribute to research in this area, the study sought to evaluate how women and girls are portrayed in the children story books and what messages such portraiture gives to the children about women in the society.

2.3. Common Motifs of Gender Portrayal in Literature

- In general literature, various motifs have been used in portraying women[30]. Some of these motifs are presented below:

2.3.1. Portrayal Based on Sex

- This view considers sex as a category distinguishing males from females in terms of biological characteristics which may be listed under two considerations: First, secondary sex characteristics such as women having breasts and men growing beards or developing a deep voice. Secondly, the physiological functions like pregnancy; giving birth or breast feeding is for women while the men are associated with reproduction.Portrayal based on sex entails physical and tangible attributes, which the writer apportions his/ her character on the basis of anatomy or sex roles. In attempting to portray the maleness or femaleness of their characters, writers often use the attributes of physical features and physical strength. The further back one goes in African fiction, the more pronounced is society’s preference for male offspring and the more insignificant is the woman’s presence and action in such fiction. This trend is in keeping with the return to the mainspring of traditional culture and therefore to its patriarchal beginnings[31].

2.3.2. Portrayal Based on Physical Features

- The physical feature is used to refer to the way a writer describes his characters in relation to their body build. By referring to physical features, the writer distinguishes female characters from male characters by associating particular attributes to femaleness or maleness. In a patriarchal society like the Kenyan one, male physique is exclusively big, strong and unconquerable while the female is invariably frail and vulnerable. This vulnerability is what is often used to justify the societal view that women or girls always need the physical protection of the men or boys.

2.3.3. Portrayal Based on Gender Roles

- The dominant literary attitude has been to present the woman as an insignificant figure in the daily politics of village life, unearthing in the process the detestable disadvantages of her day-to-day existence. Villagers have evolved from just acquiescent components of a group into individuals with choices and preferences. The emergence of an individualistic society also provides the appropriate framework for the analysis of character and for a more comprehensive appreciation of gender roles[30].

2.3.4. Gender Stereotypes in Children’s Literature

- A majority of the studies that have analyzed gender stereotypes within children’s literature have focused on character prevalence in titles, pictures and central roles, and on gender differences in the types of roles and activities associated with the characters. Although more recent studies reveal that gender differences in children’s literature have decreased considerably toward more sexual equality, with female representation as main characters becoming proportionate to that of male characters[32], research indicates that this has been an issue for years and more needs to be done[21, 30-31].Angela and Mark Gooden[21] analyzed 81 Notable Books for Children from 1995 to 1999 for gender of main character, illustrations and title. The authors concluded that steps toward equity had advanced based on the increase in females represented as main characters; however, gender stereotypes were still significant in children’s picture books. As hypothesized, female representation as the main character equally paralleled that of males, but males appeared alone more often than females in the illustrations. And, although there was an emergence of non-traditional characteristics and non-traditional roles portrayed by females and males, males still dominated the children’s literature reviewed.A study done in 2003 took a look back at progressive change in the depiction of gender in award-winning picture books for children[33]. The authors concluded that books from the late 1940s and late 1960s had fewer visible female characters than those from the late 1930s and late 1950s, but that characters in the 1940s and 1960s were less gender stereotyped than the characters from the 1930s and 1950s. The results were interpreted as having a direct correlation with the level of conflict over gender roles during each time period.In 2006, Hamilton and colleagues[34] conducted a twenty-first century update on gender stereotyping and underrepresentation of female characters in 200 popular children’s books. The results showed that female characters are still underrepresented in children’s picture books. There were nearly twice as many male than female main characters; male characters appeared more often in illustrations; female characters were showcased nurturing and indoors more than male characters; and occupations were gender stereotyped.Beyond character prevalence and character roles and activities, there have been some researchers who have taken different approaches to analyzing gender stereotypes within children’s literature. For example, in a study analyzing sex bias in the helping behaviour presented in children’s picture books, it was concluded that male characters were found to be represented more frequently than females both as child helpers and as the recipients of help[35].Arthur and White[36] researched children’s assignment of gender to gender-neutral animal characters. The study indicated that the youngest children most often assigned their own gender to the characters; however, the children in the older groups were influenced by stereotypes. For example, solitary and non-interacting characters were less likely to receive female gender labels than were bears involved in adult-child interactions.A study done in 1999 examined a different potential area of gender stereotyping, gender differences in emotional language in children’s picture books[37]. It was hypothesized that there would be a relationship between gender and the amount of emotional words associated with each characters, and that male characters would more often be associated with emotional words considered appropriate for males, while female characters would more often be associated with emotional words considered appropriate for females. The analysis of character prevalence indicated that males had a higher representation in titles, pictures and central roles. However, contrary to the hypotheses, males and females were associated with equal amounts of emotional language, and no differences were found in the types of emotional words associated with males and females.Whereas previous studies looked at the narrowly defined roles of female characters, one study focused on the representation of mothers and fathers, and examined whether men were stereotyped as relatively absent or inept partners[38]. The results of the content analysis indicated that fathers were largely underrepresented and, when they did appear, they were withdrawn and ineffectual.According to Anderson and others[34] although gender representation in children’s literature seems to be improving, we should be aware that there may be more subtle ways in which the sexes are portrayed stereotypically. They suggest a possibility that authors consciously or unconsciously resort to subtle sexism where blatant sexism is discouraged.

2.3.5. Goffman’s Model of Decoding Gender Displays and Visual Sexism

- In 1979, Erving Goffman[39] found subtle visual sexism in his examination of gender bias in advertising through such cues as relative size (women shown smaller or lower, relative to men), feminine touch (women constantly touching themselves), function ranking (occupational), ritualization of subordination (proclivity for lying down at inappropriate times, etc.) and licensed withdrawal (women never quite a part of the scene). In his book, Goffman concluded that women were weakened by advertising portrayals via these five categories. However, these categories of decoding behaviour have not been formally explored in examining the portrayal of women in written works of art. Though the model is based on the visual displays of women, it can also be used to analyse the descriptive portrayal of women in written literature.Based on Goffman’s theoretical framework, the purpose of this study was to fill the gap that exists in the existing research between studies on the portrayal of females in relation to gender behaviour patterns in advertising and the representation of females in written literature.To this end, the study explored how women and girls are portrayed in the selected classes 1 to 3 children books recommended in the Kenya Institute of Education’s The Orange Book between 2005 and 2010. Specifically, the study evaluated the gender stereotypes presented in the children books focused on the following objectives:i. To analyze the prevalence of the gender-specific behaviours mentioned in Goffman’s model in the children books.ii. To describe the messages about women given to the society through children’s literature.iii. To evaluate whether the messages in children books have changed from 2005 to 2010.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

- The study used a qualitative design in which a descriptive text analysis approach was adopted. The study relied on a close textual reading of the selected children texts which was informed by social changes in the Kenyan society.

3.2. Sample

- The data used for this study were picture storybooks dealing with the experience of starting school. Kenya Institute of Education annually publishes a list of recommended course and supplementary reading texts for all classes in Primary and secondary education in The Orange Book. In this study, over 100 children’s books for classes 1 to 3 listed in the Orange Book between 2005 and 2010 were consulted. Of these, 40 met the criteria of picture storybooks, in that both text and illustrations combined to tell the story. Books that were not considered include readers–where the text was supported by an occasional illustration–and books that clearly related to starting child care, or preschool, rather than formal school. Where books were described as relevant across different stages–for example suitable for classes 1-3, they were included in the sample. The picture storybooks studied were all written in English. The books are currently available in the major retail outlets.

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

- Five forms of gender displays espoused in Goffman’s theoretical framework were evaluated: relative size, feminine touch, function ranking, ritualization of subordination and licensed withdrawal. The dependent variable was the frequency of gender displays in the selected book, and the independent variable was the year of publication. Coding was based on the following criteria for each category: Relative Size – Male taller; the height of male and female models are compared (Male taller =1, Male not taller = 0); Feminine Touch – Cradling and/or caressing object, touching self; the women is described in the illustration using her fingers and hands to trace the outline of an object, to cradle it or to caress its surface (Yes = 1, No = 0); Function Ranking – Male as the instructor, female serving other person, male in superior role; the man is instructing the women in the illustration (Yes = 1, No = 0); Ritualization of Subordination – Female lowering, lying/sitting on sofa (Yes =1, No = 0); Licensed Withdrawal – Expansive smile, covering mouth/face with hand, head/eye gaze aversion, phone conversation, withdrawing gaze, body display; the female is described as withdrawn or removed (mentally and/or physically) from a particular situation (Yes = 1, No = 0).

3.4. Data Analysis

- As with Kang’s study[22], a content analysis was performed. For each coding category, different scores were assigned: the score of one if it is a stereotypical behaviour and the score of zero if it is a nonstereotypical behaviour. By adding up the scores, the overall gender display score for the selected book was measured. Therefore, a higher score indicated more stereotyping, and a lower score indicates less stereotyping. The mean stereotyping scores for each behavioural category were then compared in order to determine an overall stereotyping score for each.

4. Results

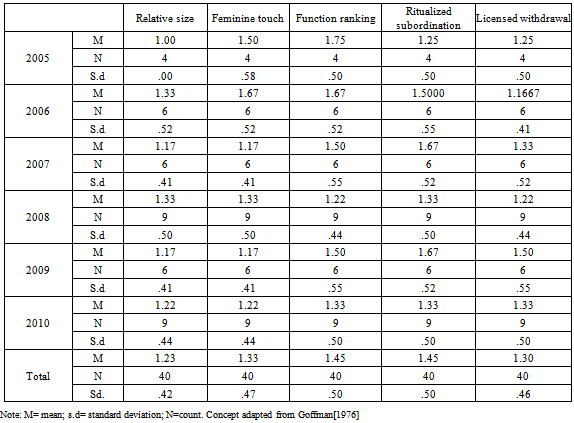

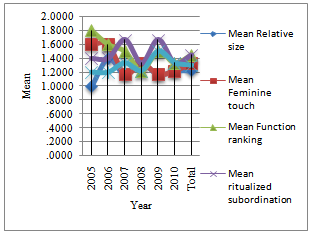

- Table 1 below gives the summary statistics for various caategories of gender displays in the analyzed books per year of publication.As seen in figure 1 above, the selected books published in 2005 had on average male characters presented as superior than female characters, female characters were on average presented as touching or cuddling objects, as lowered or sitting, and as withdrawn from a particular situation. However, men were not presented as taller than women in the illustrations.In the books published in 2006, on average male characters were mainly superior than female characters in their roles. In addition, the female characters were mainly presented as touching objects, inferior to smaller than men or in lowered or sitting positions. However, female characters were mostly presented as not withdrawn from the situation portrayed in the illustrations.In the books published in 2007, female characters were mostly presented as inferior to male characters and in postures that displayed ritualized subordination. In addition, women were withdrawn from the situations illustrated. Notably, men were mainly presented as not taller than women and fewer female characters were presented touching or cuddling objects.In the books published in 2008 and 2010, male characters were presented as taller and as taking superior roles than female characters. The female characters were described touching objects and in postures that displayed ritualized subordination to male characters. The female characters were mainly described withdrawn from the situations presented in the illustrations. However, the means for all the categories for the two years appeared to cluster between 1.2 and 1.4.In the books published in 2009, female characters were on average withdrawn from the illustrated situations. They were also shown displaying ritualized subordination or taking roles inferior to those of males. Male characters were on average not taller than their female counterparts while female characters were least presented touching objects. However, the female characters were not described as.. As shown in table 2, most books had taller male characters presented in superior roles and while women characters were mainly portrayed as lowering, withdrawn from situations and as cradling objects.A single-sample t-test compared the means of the various categories of gender displays as shown in table 3 above. Based on the extant literature, it was assumed that women are portrayed as withdrawn, submissive and inferior to men. Thus the population mean was assigned a value of 1. In the five gender display categories adapted from the Goffman model, the sample means were significantly greater than the population mean. A significant difference was found for each category thus: relative size (t (39) =3.365, p 0.05); Feminine touch (t (39) =4.333, p 0.05); both function ranking and ritualized subordination had (t (39) =5.649, p 0.05) and licensed withdrawal had (t (39) =4.0088, p 0.05).

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Figure 1. A comparison of the means of the gender displays across the years |

5. Discussion

- The findings indicate that the behaviour of women and girls based on Goffman’s model of decoding behaviour is significantly different from that of men in the selected English children books. This finding corroborates earlier studies on children texts where women were found to be portrayed negatively compared to men[35; 40]. The findings further reveal both positive and negative messages about women have been given in the selected texts. This is an important finding since gender identities, stereotypes and scripts are conceptualized from childhood and they have a powerful impact on children’s attitudes, values, beliefs and behaviours[22]. However, it appears that the pattern of presentation differs from year to year. In most instances, women are presented as second to men in function ranking. Motifs of female character presentation that seem to consistently appear throughout the years are the feminine touch, ritualized subordination and licensed withdrawal.

6. Recommendations

- It is expected that these results will inform policy and curriculum designers at Kenya Institute of Education (KIE) and the Ministry of Education as they choose and recommend the literary experience Kenya school going children are expected to be exposed to. There is a need to educate parents and teachers to use gender neutral literature and picture books that promote gender equality among the sexes. Based on the current findings, the authors are convinced that Goffman’s model of decoding behaviour offers an effective theoretical framework for analyzing gender representation in school books meant for children in an African setup. It is recommended that further research based on this model be conducted focusing on the portraits of women in supplementary reading texts for children in other classes so as to get a more comprehensive view of the frames of reference that we may be putting in place regarding gender roles for our children through our education system. A similar study can also be conducted to establish the portraits of women and girls in Kiswahili children texts recommended for Kenyan schools and a comparison be done with the English texts. This would go a long way in depicting a concrete image of the Kenyan Education system.

References

| [1] | Kohlberg, L., A cognitive-developmental analysis of children’s sex-role concepts and attitudes. In E.E. Maccoby (Ed.), The development of sex differences, Stanford University press, 1966. |

| [2] | Martin, C. L., Ruble, D., Children’s search for gender cues: cognitive perspectives on gender development, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 67-70, 2004. |

| [3] | Ruble, D.N., Taylor, L.J., Cyphers, L., Greulich, F.K., Lurye, L.E., Shrout, P.E. The role of gender constancy in early gender development, Child Development, 78, 1121-1136, 2007. |

| [4] | Liben, L. S., Bigler, R. S., The developmental course of gender differentiation, Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 67 (serial No. 269), 2002. |

| [5] | Luecke-Aleksa, D., Anderson, D. R., Collins, P. A., Schmitt, K. L., Gender constancy and television viewing, Developmental Psychology, 31, 773-780, 1995. |

| [6] | Bandura, A., Bussey, K., On broadening the cognitive, motivational, and sociocultural scope of theorizing about gender development and sunctinoning: Comment on Martin, Ruble, and Szkrybalo (2002). Psychological Bulleting, 130, 691-701, 2004. |

| [7] | Robert V. Kail, John C. Cavanaugh, Human Development, A Life-span view, 5th ed. Wadsworth, USA, 2010. |

| [8] | Geary, D. C., Sexual selection and human life history. In R. V. Kail (Ed), Advances in child development and behavior (vol. 30, pp. 41-102), Academic press, USA, 2002. |

| [9] | Iervolina, A,C., Hines, M., Golombok, S.E., Rust, J., Plomin, R., Genetic and environmental influences on sex-typed behavior during the preschool years, Child Development, 77, 1822-1841, 2005. |

| [10] | Pasterski, V. L., Geffner, M. E., Brain, C., Hindmarsh, P., Brook, C., Hines, M., Prenatal hormones and postnatal socialization by parents as determinants of male-typical toy play in girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Child Development, 76, 264-278, 2005. |

| [11] | Smith, E. R., Mackie, D. M., Social psychology (2nd ed.), Psychology Press, USA, 2000. |

| [12] | Serbin, L. A., Poulin-Dubois, D., Colburne, K A., Sen, M. G., Eichestedt, J. A., Gender stereotying in infancy: Visual preferences for and knowledge of gender-stereotyped toys in the second year, International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25, 7-15, 2001. |

| [13] | Gelman, S. A., Taylor, M. G., Nguyen, S. P. Mother-child conversations about gender. Monographs of the society of Research in Child Development, 69 (275), 2004. |

| [14] | Giles, J. W., Heyman, G.D., Young children’s beliefs about the relationship between gender and aggressive behavior, Child Development 76, 107-121, 2005. |

| [15] | Etaugh, C., Liss, M. B., Home, school, and playroom: Training grounds for adult gender roles, Sex Roles, 26, 129-147, 1992. |

| [16] | Levy, G. D., Taylor, M. G., Gelman, S. A., Traditional and evaluative aspects of flexibility in gender roles, social conventions, moral rules and physical laws. Child Development, 66, 515-531, 1995. |

| [17] | Arbuthnot, M. H., Children and books. Chicago, Scott Foresman & Company, USA, 1984. |

| [18] | Bender, D. L., Leone, B., Human sexuality: 1989 annual, Greenhaven Press, USA, 1989. |

| [19] | Temple, C., Martinez, M., Yokoto, J., Naylor, A. Children’s books in children’s hands: An introduction to their literature, Allyn & Bacon, USA, 1998. |

| [20] | Stephens, J. Language and ideology in children’s fiction, Longman, UK, 1992. |

| [21] | Angela Gooden, Mark Gooden, Gender Representation in Notable Children’s Picture Books: 1995-1999. Sex Roles, 45(1/2), 89-101, 2001. |

| [22] | Kang, M. E. The portrayal of women's images in magazine advertisements: Goffman's gender analysis revisited. Sex Roles, 37(11/12), 979-997, 1997. |

| [23] | Easley, A., Elements of sexism in a selected group of picture books recommended for kindergarten use, East Lansing, MI: National Center for Research on Teacher Learning, (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED104559), 1973. |

| [24] | Narahara, M. (1998). Gender stereotypes in children’s picture books. East Lansing, MI: National Center for Research on Teacher Learning. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED419248) |

| [25] | Peterson, S. B., Lach, M. A., Gender stereotypes in children’s books: Their prevalence and influence on cognitive and affective development. Gender and Education, 2, 185–196, 1990. |

| [26] | Weitzman, L.J., Eifler,D., Hokada, E., Ross,C.,Sex-role socialization in picture books for preschool children. American Journal of Sociology, 77, 1125–1150, 1972. |

| [27] | Crabb, P. B., Bielwaski, D., The social representation of material culture and gender in children’s books. Sex Roles, 30, 69–79, 1994. |

| [28] | Weiller, K. H., Higgs, C. T., Female learned helplessness in sports: An analysis of children’s literature. Journal of Physical Education, 60, 65–67, 1989. |

| [29] | Kenya Institute of Education (KIE), Kenyan Primary School Syllabus, KIE, Kenya, 2002. |

| [30] | Oyewumi, O. (Ed.) African Women and Feminism: Reflecting on the Politics of Sisterhood, African World Press, USA, 2003. |

| [31] | Egejuru, P. A. (Ed.) Nwanyibu: Womanbeing and African Literature, Trenton: African World Press, 1997. |

| [32] | Henderson, D., Kinman, J., An analysis of sexism in Newberry Medal Award books from 1997 to 1984. The Reading Teacher, 38, 885-889, 1985. |

| [33] | Clark, R. Guilmain, J. Saucier, R. K., Tavarez, J., Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: The Presence of Female Characters and Gender Stereotyping in Award-Winning Picture Books Between the 1930s and the 1960s, Sex Roles, 49(9/10), 439-449, 2003. |

| [34] | Anderson, D., Broaddus, M., Hamilton, M., Young, K., Gender Stereotyping and Under-representation of Female Characters in 200 Popular Children’s Picture Books: A Twenty-first Century Update, Sex Roles, 55, 757-765, 2006. |

| [35] | Leslie Dawn Helleis, Differentiation of Gender Roles and Sex Frequency in Children’s Literature, Ph.D. dissertation, Maimonides University, USA, 2004. |

| [36] | Arthur, A., White H., Children’s Assignment of Gender to Animal Characters in Pictures, The Journal of Psychology, 157(3), 297-301, 1996. |

| [37] | Cassidy, K. W., Tepper, C., Gender Differences in Emotional Language in Children’s Picture Books, Sex Roles, 40(3/4), 265-280,1999. |

| [38] | Anderson, D., Hamilton, M., Gender Role Stereotyping of Parents in Children’s Picture Books: The Invisible Father, Sex Roles, 52(3/4), 145-151, 2005. |

| [39] | Goffman Erving, Gender advertisements, Harvard University Press, UK, 1979. |

| [40] | Claudia Rosa Acevedo, Carmen Lidia Ramuski, Jouliana Jordan Nohara, Luiz Valério de Paula Trindade, A Content Analysis of the Roles Portrayed by Women in Commercials: 1973 – 2008, REMark - Revista Brasileira de Marketing, São Paulo, 9(3), 170-196, Brazil, 2010. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML