-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Archaeology

p-ISSN: 2332-838X e-ISSN: 2332-841X

2021; 9(1): 41-46

doi:10.5923/j.archaeology.20210901.08

The “Kouroi of Atalanti”: Limestone Funerary Statues and Grave Stele from the Cemetery of Ancient Opous (Atalanti): Preliminary Study, Analysis and Investigation of the Composition, Variety and Possible Sources of Limestone of a New Locrian Sculpture Workshop

Maria I. Papageorgiou1, Theodore Ganetsos2

1Greek Ministry of Culture, Department of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, Ephorate of Phthiotida and Evrytania, Lamia, Greece

2University of West Attica, Laboratory of Non-Destructive Techniques, Engineering Faculty, Athens, Greece

Correspondence to: Theodore Ganetsos, University of West Attica, Laboratory of Non-Destructive Techniques, Engineering Faculty, Athens, Greece.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Of exceptional importance for Central Greece and for the art of Archaic sculpture in general, considering their scarcity, are the funerary limestone statues that came to light by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Phthiotida and Evrytania at the east fringes of Atalanti, at the end of 2018. Statues are only part of the wider monumental landscape of the unknown organized ancient cemetery, a small part of which was unearthed at the east edge of Opous (Atalanti), the capital of ancient Locris. Additionally, during the excavation, which is still in progress, 15 tombs have been investigated, most of them undisturbed. These contained single adult and infant burials, accompanied by plentiful and significant artefacts, such as terracotta figurines, bronze vessels and mirrors, as well as silver and glass jewels, dated from the 6th to the 2nd century B.C. The cemetery is still under study, yet unpublished, and the current article is the first preliminary report for the mainly life-sized limestone statues and grave stele. The exceptional and innovative stylistic features of the statues and the unique way of their standing indicates that they were created by an unknown Locrian Sculpture Workshop that was active in the region –according to our current knowledge- from the 6th to the mid.- 5th century B.C. Analyses have been carried out in order to investigate the diversity of the limestone composition from which sculptures and grave stele were made, to identify further distinct groups with different chemical composition and finally to locate possible quarries or regions of East Locris that functioned as the sources of limestone extraction. New technology equipment applied in order to identify specific characteristics of the limestone statues and grave stelae. The 3D measurements of the statues were performed on a Shining 3D Einscan 2X 3D Scanner. The scanner was set up to acquire in, Feature-only Rapid Mode with a resolution of 0.2mm. For post processing, quality option was selected. XRF in-situ measurements were carried out in order to investigate the diversity of the limestone composition from which sculptures and grave stele were made. We identified distinct groups with different chemical composition and after a useful comparison with XRF data from 9 different regions of East Locris we found the possible provenance of the sources of limestone extraction.

Keywords: Kouroi of Atalanti, 3D scanning, Provenance

Cite this paper: Maria I. Papageorgiou, Theodore Ganetsos, The “Kouroi of Atalanti”: Limestone Funerary Statues and Grave Stele from the Cemetery of Ancient Opous (Atalanti): Preliminary Study, Analysis and Investigation of the Composition, Variety and Possible Sources of Limestone of a New Locrian Sculpture Workshop, Archaeology, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2021, pp. 41-46. doi: 10.5923/j.archaeology.20210901.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The modern town of Atalanti is located in the eastern part of Locris, a rather narrow zone of Mainland Greece, among the Eubeoan Gulf, Phokis and Boeotia. It is built at the foothills of Chlomos Mountain, where ancient Opous, the capital of Locris, flourished during ancient times. The discovery of the funerary limestone statues is of exceptional importance for Central Greece and for the art of Archaic sculpture in general, in terms of their typology and scarcity. The first statue was discovered by a local farmer at the east fringes of Atalanti, during the end of 2018 [1-2] who kindly informed the Ephorate of Antiquities of Phthiotis and Evrytania, which then undertook the excavation of this area (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. The limestone statues known as the kouroi of Atalanti |

2. The Limestone Sculptures Known as “The Kouroi of Atalanti”

- I. Fragmentary statue of Hercules, Atalanti Archaeological Museum, inv. no. L 1776, (Figure 2).Dimensions: height 1.22 m, width 0.43 m. Limestone (poros).The life-size poros statue belongs to the type of Hercules, which preserves the head and the entire body down to the lower part of the thighs. The hands are missing and the state of preservation of the face and body is not good. The bearded figure stands strictly frontal, with the left leg extended “in the type of kouros”. Its uniqueness lies on the fact that the three quarter of the body is presented in-the-round, while the rear surface of the statue is flat in the upper part, having an integral rectangular socle for placement into an unknown monument or pediment. 3D digitization of the statue confirmed our original hypothesis, that it may be a statue of Hercules, as the high resolution brought to light the front legs of the lion skin tied in the center of the chest, its tail, which is formed behind the right buttock of the statue. Concerning the part of the head, we can easily distinguish the head of the lion skin, while the lower jaw of the animal is embossed, on both sides of the neck of the statue. The absence of ears, which were replaced by a rectangular groove on the right and an oval on the left, remains enigmatic. (It may be related to inlay material of some kind, or it belonged to a larger statue group). Stylistically, it bears some affinities with another unique work, deriving from a Boeotian workshop; the grave stele of "Kitylos and Dermys" from Tanagra displayed at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens [5].

| Figure 2. Fragmentary statue of Hercules, first quarter of the 6th century BC |

| Figure 3. Fragmentary statue of a “kouros”, early to middle archaic period |

| Figure 4. Fragmentary statue of a kouros, last quarter of the 6th century B.C. |

| Figure 5. Fragment of an over natural sized kouros |

| Figure 6. Fragmentary torso of a male statue, second quarter of the 5th century B.C. |

| Figure 7. The limestone grave stele reused as a cover of a burial pithos |

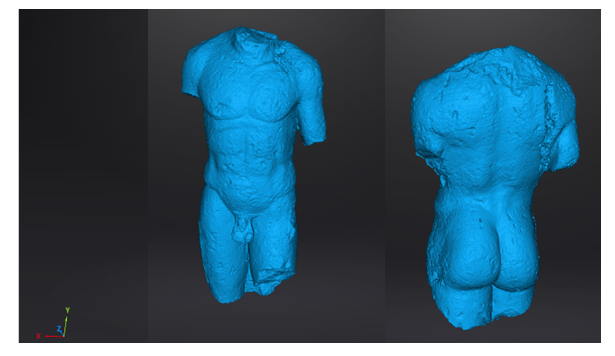

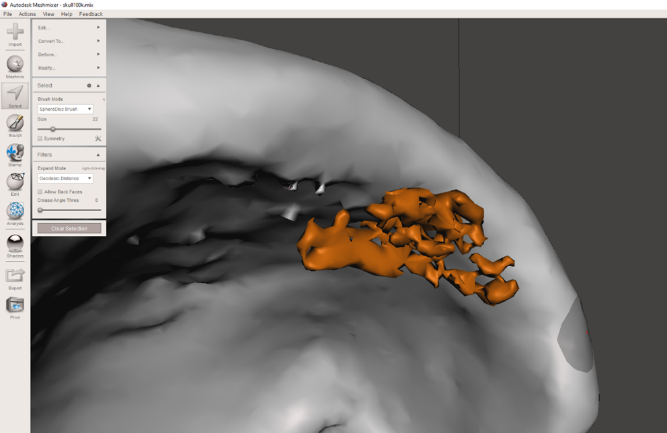

3. 3D Scanning the Statue

- The limestone sculptures known as “The kouroi of Atalanti” were 3D scanned with a EinScan Pro 2X Plus (Shining 3D Tech. Co., Ltd.) using Shining Software according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The time required to 3D scan skull was aprox. 10-15 minutes and the time required for post processing 2 hours. A feature – only rapid mode with a resolution of 0.2mm was used (figure 8). In scanning software settings, the Quality mode was enabled for post processing and also manufacture’s CAD software was used to further clean minor errors (figure 9).

| Figure 8. Results of 3D scanning in natural size kouros |

| Figure 9. Cleaning minor errors in 3D scanning procedure |

4. XRF Analyses

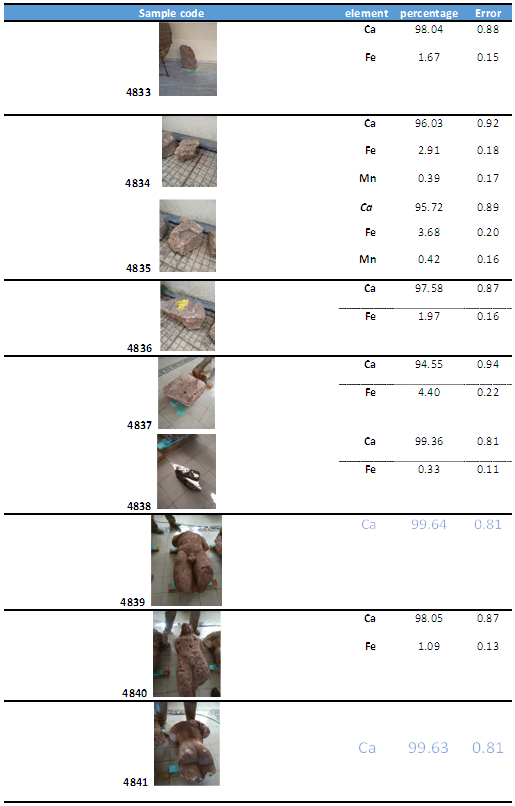

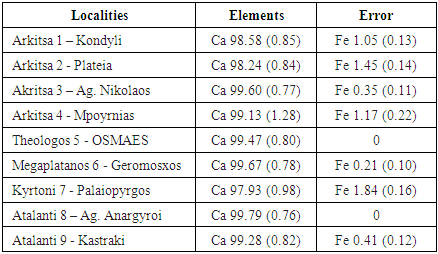

- In this work an XRF non-destructive analysis was conducted in order to identify the chemical composition of limestone of “The kouroi of Atalanti” and be compare with data of XRF from different sources of East Locris for provenance investigation (tables 1 and 2, figure 10).

|

|

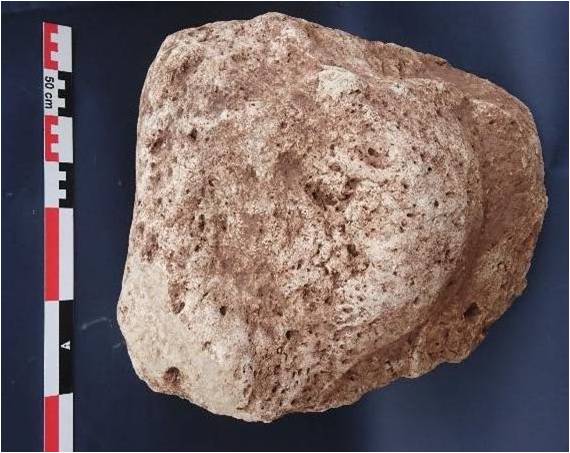

| Figure 10. Different sources (quarries) of raw material collected for the purposes of this work |

5. Conclusions

- The following conclusions can be drawn from the 3D scanning procedure of this study:• 3D scanning and 3D printing can be a very useful technology for preserving and disseminating specimens in the field of archaeology.• Can help museums and archaeologists get more value form current specimens.• Very quick to digitize, using a streamlined solution such as that available from Shining3D where both 3D scanner and 3D printer are made by the same company might accelerate procedure and help avoid PROBLEMS (file translation, 3D printer setup).Also, XRF in-situ measurements were carried out in order to investigate the diversity of the limestone composition from which sculptures and grave stelae were made. We identified distinct groups with different chemical compositions and after a useful comparison with XRF data from 9 different regions of East Locris we found the possible provenance of the sources of limestone extraction for the sample codes of Table 1: 4839 (L.1781, Figure 4), 4841 (L. 1775, Figure 6). The absence of Fe and the concentration of Ca in these two statues are closer to the chemical composition of the locations Atalanti 8-Ag. Anargyroi and Theologos 5-OSMAES (Table 2). An ancient quarry of limestone (poros) is mentioned in earlier studies [10,11] among other quarries of Phthiotis in the locality in this study No 5 “Theologos 5-OSMAES” where the examined sample 5 was collected. The quarry is located in the north part of the city of ancient Alai, where in our days the village of St. Ioannis Theologos of Malesina stands. In earlier studies the record name “Quarry 3” [11] has been described as an outdoor type of limestone quarry. Furthermore, the chemical composition of the Hercules’ statue, sample code 4840 of Table 1 (L1776, Figure 2) that contains Ca 98.05, Fe 1.09 is close enough to the sample collected and examined from the Locality Arkitsa 1-Kondyli (Ca 98.58, Fe 1.05). In addition, the high concentration of Fe (1.97 to 3.68) in three of the five examined grave stelae and the existence of Mn in the samples, leads to the conclusion, at this preliminary study, that more samples of limestone need to be collected from the region for further examination. As grave stelae were works of mass production and very common for each burial, in contrast with the sculptures, sources of limestone should probably be investigated closer to the city of ancient Opous in future studies. Concluding, at this preliminary study which is going to be enriched in the future with more samples and measurements, the initial hypothesis about the use of local material for sculptures is confirmed and furthermore we have the identification of a new Lokris workshop for monumental sculpture, active during 6th c. B.C. and first half of 5th c B.C., which uses different types of limestone from local sources, depending on the type of the sculpture.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML