-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Archaeology

p-ISSN: 2332-838X e-ISSN: 2332-841X

2020; 8(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.archaeology.20200801.01

Received: Oct. 16, 2020; Accepted: Nov. 6, 2020; Published: Nov. 15, 2020

A Catalogue and Inventory of Cultural Heritage Sites, Artefacts and Features in Kisumu City and Its Environs in Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya

Fredrick Odede, Fredrick Owino, Patrick Hayombe, Stephen Agong

JOOUST, Kenya

Correspondence to: Fredrick Odede, JOOUST, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Most of the cultural heritage sites, artifact and features are under constant threat from human activities and natural processes. Oral traditions of these sites are under threat. This threat is occasioned by the lack of appreciation of oral traditions as authentic transmitter of history. KLIP is keen at conducting documentation of the existing oral traditions related to these sites both in print and audio for future generations. The most serious problem faced is the grabbing of cultural heritage sites for human activities. Extensive conditional survey and documentation should be undertaken to assess their condition and facilitate their conservation, preservation and restoration for sustainable use by the local communities living around them. Even though some of these sites are gazzetted and managed or protected by the National Museums of Kenya, there is very little community involvement in their management and use. This work highlights the state of knowledge, and the condition of some of these cultural heritage sites as well as areas for future research.

Keywords: Catalogue, Inventory, Cultural heritage, Sites, Artifacts, Features, Conservation, Preservation, Kisumu city, Environs, Lake Victoria Basin

Cite this paper: Fredrick Odede, Fredrick Owino, Patrick Hayombe, Stephen Agong, A Catalogue and Inventory of Cultural Heritage Sites, Artefacts and Features in Kisumu City and Its Environs in Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya, Archaeology, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.archaeology.20200801.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

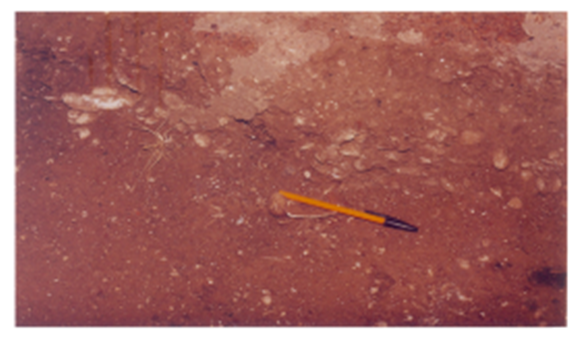

- Kisumu and its environs have very rich cultural heritage ranging from paleontological archaeological and historical to cultural sites. This work presents information regarding some sites in Kisumu and its environs. A few sites are gazzetted (under the protection of the National Museums of Kenya). However, the majority of sites in this region have been identified but not mapped or well documented. Archaeological and paleontological research has mainly been undertaken in the region. Preliminary survey of this region has revealed numerous sites in Kisumu, Bondo, Homa Bay, Migori and Siaya Counties that are yet to be located and mapped.Under enormous threat from urbanism and westernization, as well as general heritage deterioration through cultural and natural processes and rapidly declining economic growth in traditional areas such as fishing and agriculture, Kisumu City nonetheless boasts of diverse cultural heritage resources that are uniquely and spatially distributed on the landscape laced with scenic landforms that traverse the city and its environs. As one moves across the city into the Lake Victoria shores, a myriad of cultural and natural features and artefacts dot this unique lacustrine region of western Kenya. Unfortunately, the majority of these sites, artefacts and features are under serious threat (Figure 1) from both cultural and natural processes. The most serious problem is the grabbing of gazzetted sites. An urgent conditional survey and documentation should be undertaken to assess their condition and facilitate their conservation, preservation and restoration for sustainable use by the local communities living around them. Even though some of these sites are gazzetted and managed or protected by the National Museums of Kenya, there is very little community involvement in their management and use.

| Figure 1. Change of Use Due to Human Activities |

| Figure 2. Cultural Heritage Sites in Kisumu and its Environs in Kenya |

2. Study Objective

- To document and produce a catalogue of the various forms of cultural heritage sites, artifacts and features in Kisumu and its environs, Kenya.

3. Methodology

- This work aimed at mapping the locations and spatial distribution of cultural, historical and archeological sites, artifactual remains and features in Kisumu and its environs. Mapping is the key to accurate recording of surviving features and artifacts (Renfrew and Bahn, 1991). Foot survey was used to identify sites because it is the most effective means of locating sites and producing the most complete records (Hester, 1976). Topographical maps also led to the identification and mapping of sites and features. GIS was also used to locate the positions of the sites. Conditional survey was employed to assist in the assessment of the preservation state of the sites and associated artifacts. Both oral interviews and focus group discussions were used to get information about the sites. Actual observation across the sites also assisted in the assessment of the site content, quality of preservation and associated challenges. Spatial analysis and thematic analysis were used to analyze various forms of data collected.

4. Research Findings and Discussions

- Knudson, (1978) defined a site as any area of the landscape, which has evidence of pas human activities or occupation. The notion of a site as a spatial concentration of artifacts (by-product modification of natural environment) as well as myths and legends were adopted in this study. Proponents of this approach include Heizer and Graham (1967), and Fagan (1981). An alternative approach considers sites as places where artifacts, features, structures, organic and environmental remains are found together, was brought forward by Renfrew and Bahn (1991). In the new approach, a site is studied in relation to geomorphological forms and the immediate environment (Zvelebel and Macklin, 1992). Features are those aspects of cultural heritage sites that are too large, bulky, or difficult to be presented from their original context to the laboratory for in-house analysis and are therefore simply recorded, photographed or drawn (Knudson, 1978). Artifacts on the other hand, are humanly made or modified portable objects (Fagan, 1981) such as pottery, stone tools, bones, iron implements, sculptures, ethnographic remains and many others.A. Cultural Spaces in Kisumu CityThey include Aguch Kisumu, Oile Park, Jubilee Markets, Social Halls, Kisumu Museum. Places such as Aguch Kisumu, Oile Park, Jubilee Markets, Social Halls and Kisumu Museum represent varied values to urban users ranging from livelihood spots like market places to green urban spaces which reduce and control environmental pollution as well as provide recreational functions for unemployed urban dwellers, and social gatherings such as table-banking women’s groups. Initial mapping reveals the value of everyday social and recreational spaces which reveal values associated with cultural heritage and nourish the lives of residents and visitors, including Aguch Kisumo and the cultural infrastructure of the city – found in the cinema, disco, hotels, markets, clubs and restaurants.

| Figure 3. Jubilee Market in Kisumu city |

| Figure 4. Gunda Pudha in the outskirts of Bondo Township |

| Figure 5. An Archeological Site in Ulowa |

| Figure 6. Thimlich Ohinga Site in Migori |

| Figure 7. Asembo Stone-Walled Enclosure Site |

| Figure 8. Gunda Buche: Architectural Features C. Cultural and Sacred Sites |

| Figure 9. Aguch Kisumo in Kisumu City |

| Figure 10. Traditional Luo Festivals |

Q. Lake Victoria Beaches and Fisher fork communities: Musoma, Dunga, Kisumu Port

Q. Lake Victoria Beaches and Fisher fork communities: Musoma, Dunga, Kisumu Port R. Transport Facilities and Regional Connectivity for Cultural Tourism

R. Transport Facilities and Regional Connectivity for Cultural Tourism

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study had documented a catalogue and inventory of various forms of tangible cultural heritage in the form of sites, artifacts, and features as well as intangible cultural heritage such as festivals, traditional dances and songs, myths and legends in Kisumu and its environs. Several cultural heritage sites laced with various forms of artifacts and features are spatially distributed across Kisumu and its environs. They range from paleontological, archaeological, historical, and cultural heritage sites situated in the midst of natural and man-made ecological settings along the Eastern shores of Lake Victoria of Kenya. Paleontological sites exhibit evidence of fossilized bone remains dating to millions of years ago. Archaeological sites display artifactual remains spnning from stone tools, bone remains, shell middens, Early to Late Iron Age tools, pottery, charcoal remains as found at Kanam and Kanjera, Wadh Lang’o, Gogo Falls, Muguruk among others. Historical sites are endowed with both tangible and intangible cultural heritage such as dry stone walls, earth works, pottery, beads, iron implements (tangible heritage) as well as myths, and legends (intangible). Cultural sites are generally sacred sites usually visited by various religious groups to worship and engage in fasting and meditation. These are sources of herbal medicine and associated supernatural forces where different religious groups, both traditional and African-christian in nature come to obtain spiritual powers or divination.The recommendations include the need for further extensive and general survey covering the whole of western Kenya region. There is need for site conditional survey to establish specific conditions of each and every site. Conservation and preservation of the numerous endengered cultural heritage sites in Kisumu and its environs. Infrastructural developments should be of high priority to allow accessability and visibility of these sites. Awareness creation regarding the values of cultural heritage sites is of great significance to future generations. Capacity building among the key stakeholders is required for proper management of these sites. Marketing and branding of the various cultural heritage sites, their associated features and artifacts for cultural tourism promotion. Need for creation of networks, partnerships and collaborations among the key stake-holders such as local community, policy makers, academia, private practitioners, international community among others.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors of this article wish to thank all the respondents from the three cultural heritage sites, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST), Kisumu Local Interaction Platform (KLIP) secretariat for their various support, which contributed to the success of this study. We further appreciate the support from Mistra- Urban Futures (M-UF)/Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) that has enabled cultural heritage to become an important component of urban sustainability initiative in Kisumu city. Their active support and discussion contributed greatly to the success of the study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML