-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Archaeology

2015; 4(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.archaeology.20150401.01

Sufis and Dervishes' Belongings through Indian - Mongolian Illustrations

Hamada Thabet Mahmud Ahmed1, Ramy Mohseen Younis Elmarakby2

1Department of Islamic Archaeology, Faculty of Archaeology, Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt

2Researcher in the Ministry of Archaeology

Correspondence to: Hamada Thabet Mahmud Ahmed, Department of Islamic Archaeology, Faculty of Archaeology, Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Indian Sufis and dervishes' belongings have been varied to include ritual, food, smoking and drinking tools. Through studying these belongings, it is possible to highlight the customs, traditions and rituals of that group during the Mongolian rule in India. This study gains special importance in the light of the notable role of Sufis in India during that period and the fact that they received a special care from the Mongol emperors in India. Paper addressing the period of Mughal India. Mughal dynasty Muslim dynasty of Turkic-Mongol origin that ruled most of northern India from the early 16th to the mid-18th century, after which it continued to exist as a considerably reduced and increasingly powerless entity until the mid-19th century. The Mughal dynasty was notable for its more than two centuries of effective rule over much of India, for the ability of its rulers, who through seven generations maintained a record of unusual talent, and for its administrative organization. A further distinction was the attempt of the Mughals, who were Muslims, to integrate Hindus and Muslims into a united Indian state. The study sources In this paper many Such as, Mohammed Imran, Dictionary of Popular Music Egyptian terms and Ananda K. Coomara Swamy, An introduction to Indian art.

Keywords: Sufis - tampora

Cite this paper: Hamada Thabet Mahmud Ahmed, Ramy Mohseen Younis Elmarakby, Sufis and Dervishes' Belongings through Indian - Mongolian Illustrations, Archaeology, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2015, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.archaeology.20150401.01.

Article Outline

First - Belongings Used for Food, Drink and Smoking

1. Tools Used for Singing and Dancing

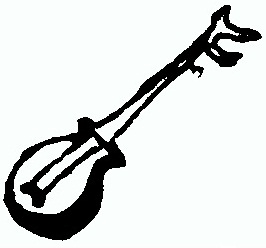

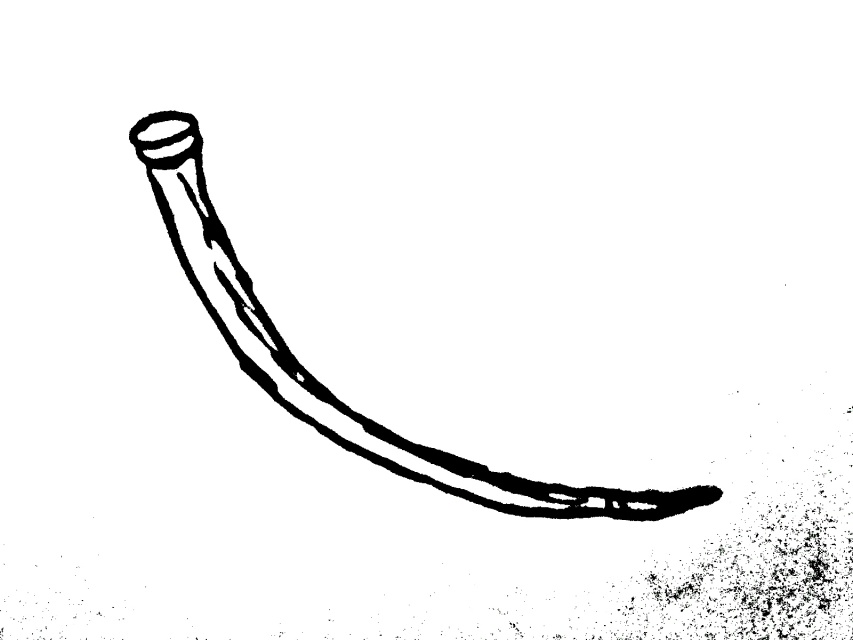

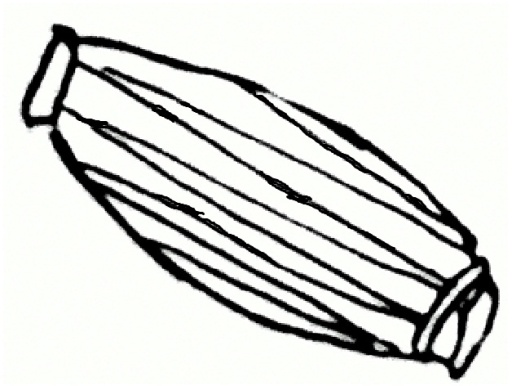

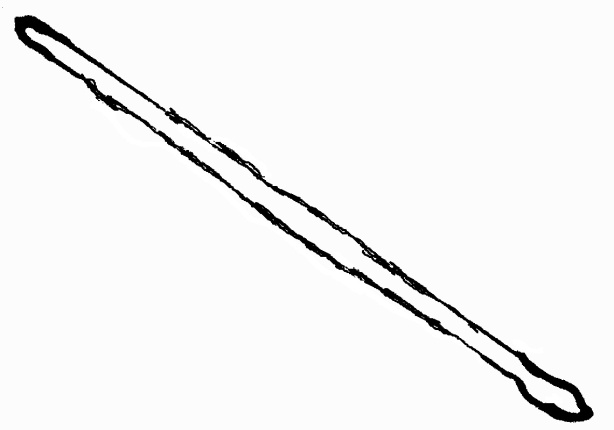

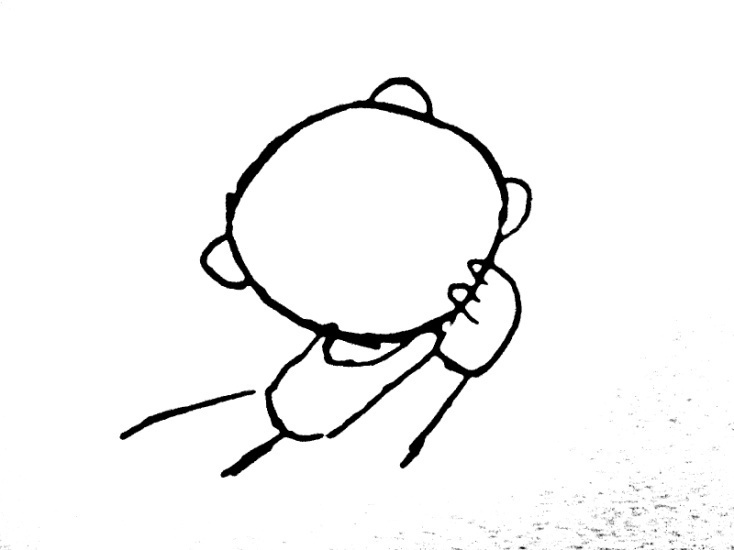

- Singing and dancing are relevant features to Sufis and dervishes1, whereas Sufis, among the people of morals and ethics, looked at both of them in philosophical terms2 and were interested in mastering them accordingly. Sufis called listening to the composed poems a "Passion" when combined with acts such as dancing, applause and musical instruments3. Jalal Addin Al-Rumi, who mentioned the music in his book Al-Mathnwi4, was the person who firstly introduced the music into the Sufism and considered it one of its main features as the depictions show. There is a widespread acknowledgment that these depictions have a great familiarity with the Iranian ones5. The tools were varied. Below we will study these instruments and tools. a) The Tanpura (tampora)It is a futile cord musical instrument made of wood6. It is of a Persian root, and is much similar to the present day lute. It was largely common during the Mongolian era in India and this can been seen in their singing and parties' depictions. It can be noted that instrument had been one of the main instruments used at this group's parties. Sometimes, tampora was the only appeared instrument at the group's depictions (see plates 7,9,10,12,14, figures 8-12).b) Ney A pure Persian instrument, the flute is one of most important musical instruments for Sufis7. The flute takes a shape of pipe with tiny holes at its side and is provided with keys to control the sound. It works by puffing and moving fingers at the holes with a systematic rhythm. It is also known as the "punctured quill8" referring to a Persian word that means "trachea", e.g. transferring air to the pharynx and lungs9. The flute possessed a great importance for Sufis because of its tune and ting which touched their affection. The Moulouya was the group that gave much interest to the flute. It is also noteworthy that Jala Addin Al-Rumi was well aware of the flute and its symbolism, but he had been preceded by “Sanaai ELghazna” who regarded the flute as a symbol for every soul that stopped of being earthly one or even lost its survival and eternality10. Jalal Addin Al-Rumi made a connection and comparison between both the flute and pen's symbolisms. He said that while the pen point may leave a beautiful inscription and useful drawing, the flute may also reveal a form of passion whose effect might make the person lose his mind and become a powerless one11.Accordingly, the flute enjoyed a great importance and symbolism within Sufis and dervishes as shown through many depictions, such as plate (13), fig. (11).c) FluteIt is a musical instrument used by Sufis and dervishes at their several gatherings. It is said that Beni Israel were the inventors of the pipe, while Kurds12 were first people who used the mini-pipe. The Pipe is also called "sernai", "shababh13". Sufis regarded the pipe as a symbol for the human body14. It appears at plates 10. d) Horn or trumpetThe Trumpet is a concave instrument which produces a sound by blowing. The "trumpet" is a noun, its plural is trumpets15. It is a noun which is used to refer to one of the instrument which belongs to the "trumpet" family16. According to the Turkish tradition, “Monhar”, the Persian king, was the inventor of the "Trumpet". But it is well-known that the Egyptians were the first people who made it from the metal. Its appearance was related to military usages. Sasanians used it in hunting. It was a very important musical instrument during the Islamic period and was used by “Tablakhana”17.Also, it was made of dead animals' horns, dried and empty plant stalks or of leg bones (animal or human)18.It accompanied Sufis and dervishes throughout their journeys and in their daily life whereas it depicted hanged on shoulders as in plate (1,11), fig. (9) e) TaborThe tabor is a rhythmic instrument that works through knocking on its surface19. Having one thin parchment or a processed animal skin, tabor's surface takes a circle shape and is bordered by a layer of thin wood, and sometimes a metal frame (5-15cm width). Usually, knocking on the surface is done by the right hand, while the left hand holds the instrument. It may have a handle, especially those ones with the much thicker frame20. Tabors vary in sizes.The Moulouya compared the tabor to the sea that releases subsequent circle waves following being hit by the oar21.They also saw the tabor as a symbol of lover, while the holder is the beloved. The subsequent and continuous waves depict the shape of the lover whose body has bent as a result of suffering from the beloved abandonment, feeling lost and facing several pains for the sustained and eternal reunion. Mulana Al-Rumi has featured this meaning through the following poetry :ولكننى كالدف فى حينما تضرب بكفك إيايأتأوة حيث تدق الوجه منى كدق الهاون22 We can translate it as the following: But I'm like the tabor, when your palm of the hand knocks on it I moan as your knock is similar to knocking on certain bowels. Tobar had been shown in many of Mongolan Indian Sufis and dervishes' depictions (see plates 7,12,13,14 figs.16)f) Parchment A rhythmic instrument with sole skin23, the parchment is similar to the tobar except that parchment has a wider wooden frame than tobar. Parchment is provided with copper or tin circle pieces (being hanged in pairs to cause special jingles following knocking on the parchment). It varies in size (small, medium and large24). The parchment appeared in many depictions of Sufis and dervishes performing their circles of remembrance. (see plates (7-10-12-13-14, fig.13)g) DrumsThe singular noun of drums is drum. The drum is an instrument that skin is stretched on. Usually it is double-faced instrument25. Man knew drums about three thousand years ago. Its design is constructed on a wooden, metal tube (In some cases the tube was a merely dried pumpkin of similar plant). Drum has one or two nozzles being covered by a sheepskin or similar material or skins (such as rabbits, cows, ibexes and fish26.)Both hands and staffs can be used to knock on drums. A hammer can be used also to make a stronger and deeper sound27. Drums sometimes are called adze28. There were many types of drums such as: Tablbaz, a small metal drum being knocked by a strip of leather of textiles; al-Koba, a drum with two circle-shaped ends covered by sheepskin, being knocked on its two surfaces by fingers and it could be hanged on the drummer's chest. The later type was the most widespread one as shown through Indian deceptions and belongings that date back to the Sasanian era and beyond29. Alrumi saw the drums as an alert and alarm tool; warning the soul or the self against the dangers around. He noted that although drums could warn the self, it could not deter the battle consequences. Drums are a symbol for the mortal world, as nothing last after their hits, and souls wish to get rid of its noise. Al-Rumi held a fine comparison between the passionate kings who love nothing but satisfying their desires, called them the dusty kings, with the drums' knocking which lasts only for a while leaving no remarkable trace. He said the following line of poetry to represent the above comparison: سوف لا تحصل على شيئ فى ذلك شعرامن ملوك التراب سوى دوى الطبولwhich can be read as follows:You will get nothing from those dusty kings but the drums sound30.We can notice drums in many plates that feature Sufis and dervishes. Those drums were of varied shapes and sizes and were embroidered with geometric trappings. (see plates 12, fig.10)

2. Prayer Beads

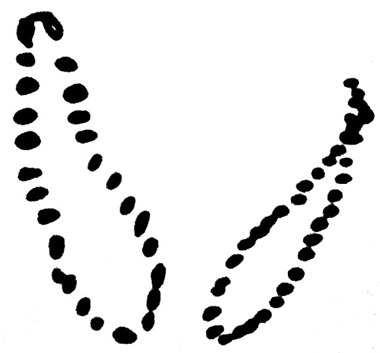

- A misbahah is a string of prayer beads which is often used to glorify and pray to Allah31. It is also known as "prayer" and "remembrance". The prayer holds it in his hand after performing the prayer, moving it while doing remembrance32 which is considered the greatest pious act the believer can do to get Allah satisfaction33, the Almighty said: and indeed the Remembrance of Allah is greater34. Allah has spoken the truth. Narrated Abu Daowd reporting the speech of Saad ibn Abi Waqas, the Prophet (PBUH) married a woman, who could be (Mother of the Believers) Safia bent Yehia, while she had kernels or tiny stones to perform remembrance using them35. Sufis, hermits and dervishes used to carry the prayer beads in order to keep remembering of Allah. To Sufis, the prayer beads refer to the darkness, meaning the darkness in which Allah has created mankind, and then Allah almighty shed light upon them. Those who get exposed to the light will be guided and those who miss it will go astray. It is said that the "misbaḥah" is the void which is not clear and does not exist; it is just images36. Prayer beads were made of cheap materials in line with abnegation and asceticism principles. This does not contradict with the fact that some Sufis tended to own precious prayer beads made of pearls37, for example, the famous Sufi Abu Al-Abbas ibn Ataa, who also used to wear the precious clothes. In addition, some Sufis and dervishes used to carry big prayer beads that were made of wood or bones38. The prayer beads have appeared in many depictions such as plates 3-5-7-8-9-10-12-14, fig. (15). Their sizes and colors were varied, but most of them consisted of 33 beads which Muslims use to repeat three phrases following each prayer 33 times. The three phrases are "Glorious is Allah", " Praise be to Allah" and "Allah is the greatest" totaling 99 times (39).Currently, prayer beads are a symbol for all Muslims, notably for Sufis and dervishes40.

3. Book

- Sufis, dervishes, hermits and ascetics appeared repeatedly in depictions holding a book, or sitting against open or closed books, commonly the holy Quran that were provided with Bukhari trappings' hardcovers, noting that Bukhari trappings were spread and still in use until our times41. (see plates 2-3-7-9-14, figs.2)These hardcovers were provided with tabs. In addition, the depicted books could be one of Sufism books that handle its foundations and teachings, or the Sufi poetry such as Al-Mathnau42 and "Mantek Al-Tayer (trans) the Logic of Birds43". Books, both the Holy Quran and Sufism teachings, repeatedly appeared with featured Sufis, dervishes and hermits44. Books have varied poses: opened, closed, or hanged on as seen at the former plates.

4. Stick (crutch)

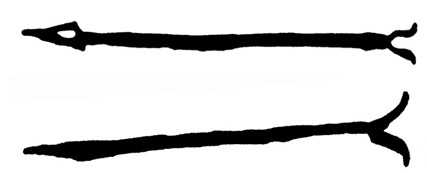

- The stick is a wooden piece used for crutching or hitting. It plural noun is staffs45. Sufis always hold them as they see it as a Sunna, a tradition derived from the Prophet (PBUH). The Prophet said: If I would like to take a tribune, Ibrahim took one too; If I would like to take a staff, Ibrahim and Moses took it too46. It is known that the stick has a great importance for the Sufis as it has a connection with Moses, PBUH, who had astaffthat was a tool to show many of Allah miracles such as nullifying the magic of Pharaoh's magicians and converting them to be believers of Allah47, Almighty, who said "And We inspired to Moses, "Throw your staff," and at once it devoured what they were falsifying. So the truth was established, and abolished was what they were doing. And Pharaoh and his people were overcome right there and became debased. And the magicians fell down in prostration [to Allah]. They said, "We have believed in the Lord of the worlds48."The stick is also involved in the story of saving Moses, PBUH, from Pharaoh who was chasing the prophet.. The story informs us that Moses has crossed the parted sea while Pharaoh and his soldiers went under the sea48. Allah, almighty, says "Then We inspired to Moses, "Strike with your stick the sea," and it parted, and each portion was like a great towering mountain. And We advanced thereto the pursuers. And We saved Moses and those with him, all together. Then We drowned the others50.Thus, stick became a tradition in view of its relations to prophets' miracles. Sufis used stick throughout their life. It was made of wood. Sufis used a very long stick with a bended upper end tomake it easy to hold it. Sometimes, it was used as a crutch or hallstand. Sometimes we found a small and thick stick at the ground beside Sufis51. The Indian stick takes shape "T" (see plates 2:9, 10, 12, fig.1,4 )

Second - Belongings Used for Food, Drink and Smoking

1. Kashkul

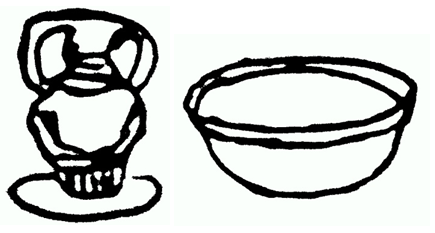

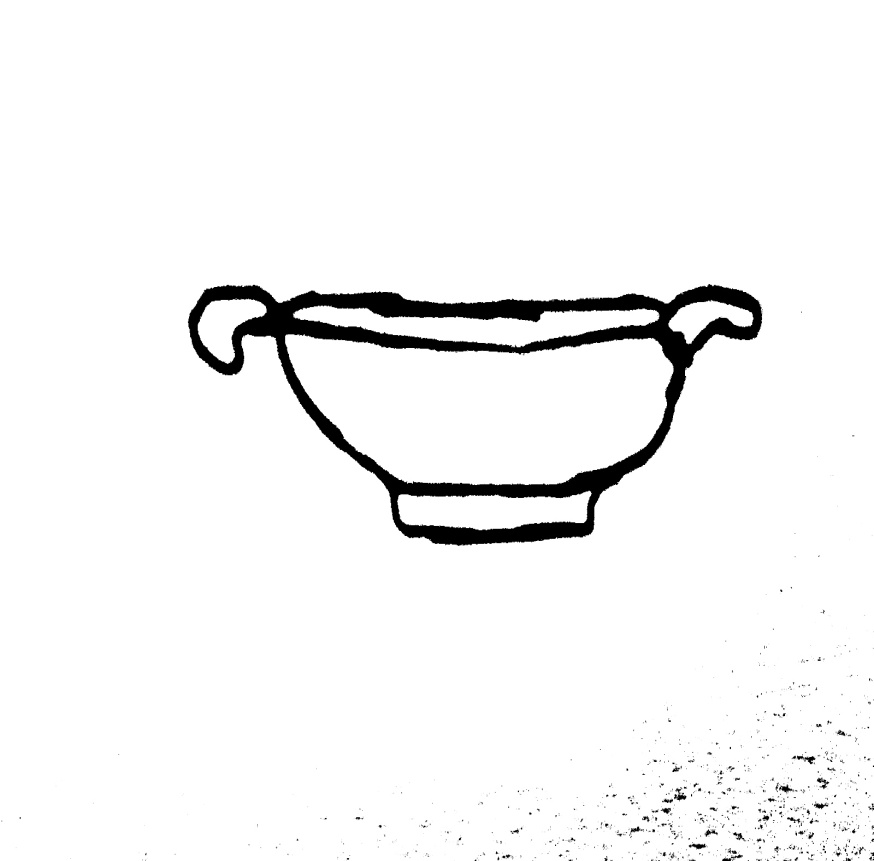

- A goblet belongs to the poor who gathers his livelihood inside it. Kashkul is a compound Persian noun: kash means drag, and kul means shoulder. It could be of an Armenian root from: gao which means collect, and hd (pronounced as hamad) which means all52.It is also called bag of the poor that they put their food inside53. It is also used by the bigger in which he puts what he collects during his day54. It is a fine piece of art, bearing many symbols and connotations expressed about by figure and trappings on it. In addition, kashkul has a unique function as a bag for both the poor, Sufis and dervishes55.Kashkul is combined with the Sufi during his journey throughout the Sufism, seeking for self and truth and his journey to the knowledge56. Sometimes kashkul took an oval figure, or a boat (ship57). Indian kashkuls mostly took the late shape as appeared in Indian Mongolian features. It had two ends of a dragon head, sometimes a head of some kind of birds made of pottery and Indian Tectonawood. Many archeologists noted that kashkul is anoval metal box (made of gold, silver or gold-plated copper) provided with carved depictions and inscriptions. They also noted that it was made of the Indian Tectonawood58. Kashkul has a correlation with Sufis and dervishes over the Islamic eras. Kashkul had some foreign names such as: "symbolical beggars bowls59", that means kashkul was a symbol to beggary; it is also known as the "Dervish bowl", and other similar names60.Kashkul is related closely to India's Sufis. Archeologists have found hundreds of them at the Shia Imams' residents in India and Iraq61. We also have several wooden kashkuls. For example there are about 1000 kashkul at Imam Ali shrine's stores; they are made of Indian Tectonawood and decorated with written inscriptions62.We also found many pottery and porcelain kashkuls within the period of study, in addition to the samples that are illustrated for Sufis and dervishes (see plates 4-5-15, fig.14 ).

2. Narghile

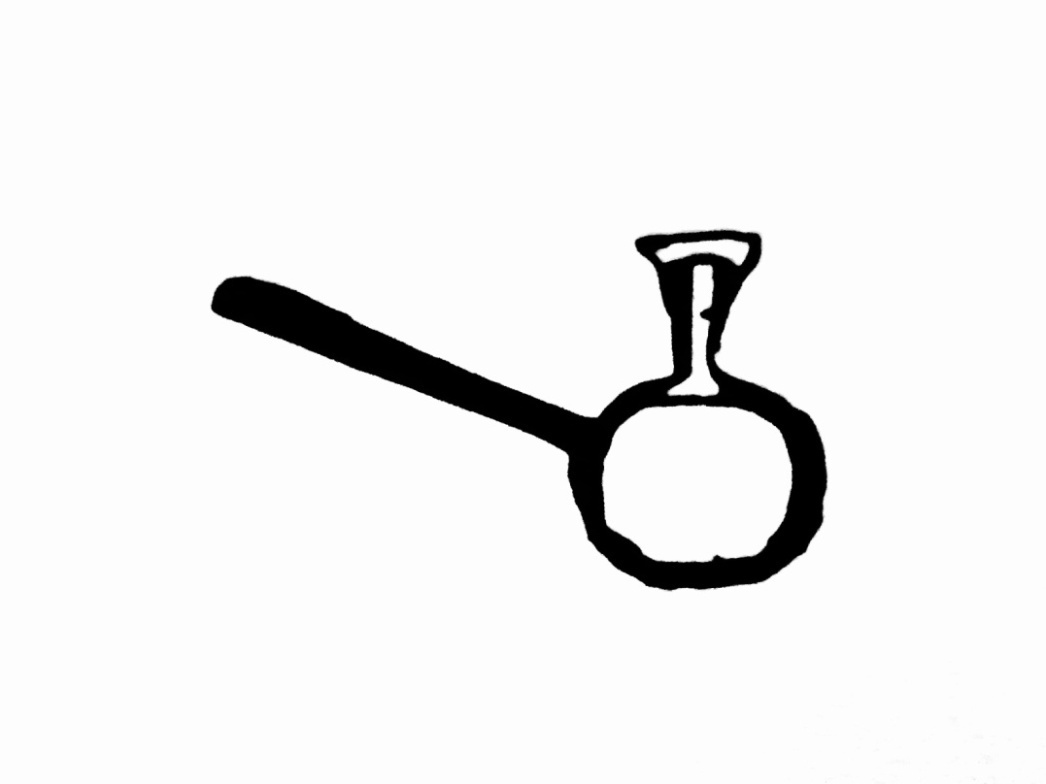

- Narghile is a Persian rooted word63, from Narkil which refers to the coconut, and narkilah which refers to a device of smoking the Persian tobacco with a base of the coconut fruit. Later that base became made of glass and other materials64. The base was punched twice, one to be headed by the tobacco stone, another to insert the tube. The word reached to the Turkish language as narkel and narkila. Plural is narageel and nargelat. Sometimes Narghile is known in Persian as Shabak.Narghile consisted of a circle base, neck and the tobacco stone. Out of the middle, there is a tube to oust the smoke. Usually, two-thirds of its size is filled with water65.Most narghiles were made of cheap materials such as wood, copper or bronze, in abidance with the Sufism principles of asceticism and abnegation. Regarding usage, two-thirds of it is filled with water. Sufis used a special type of Persian tobacco called Tonbac. This type is washed several times before its usage, and then it is put inside the tobacco stone while it is still wet. Finally, the user puts two or three pieces of hot coal. After that, the user inhales the smoke through the tube by his mouth, then the smoke moves from the stone to the cylindrical tube inside the narghile, then it moves to the water and returns to the cylindrical tube. Smoke enters the tube again then to the smoker's mouth and lungs. Smoking through Narghile is a way to filter the smoke by passing into water. Narghile body was decorated by Indian plant trappings and writings inside featured bowls66. In addition to wine and drinking, the narghile was an important tool for Sufis and dervishes to getthe feelings of passion, elevation and oblivion. Narghile appeared repeatedly in Sufis and dervishes depictions. Its body was decorated with several plant and geometric trappings (plate 6, fig.6).

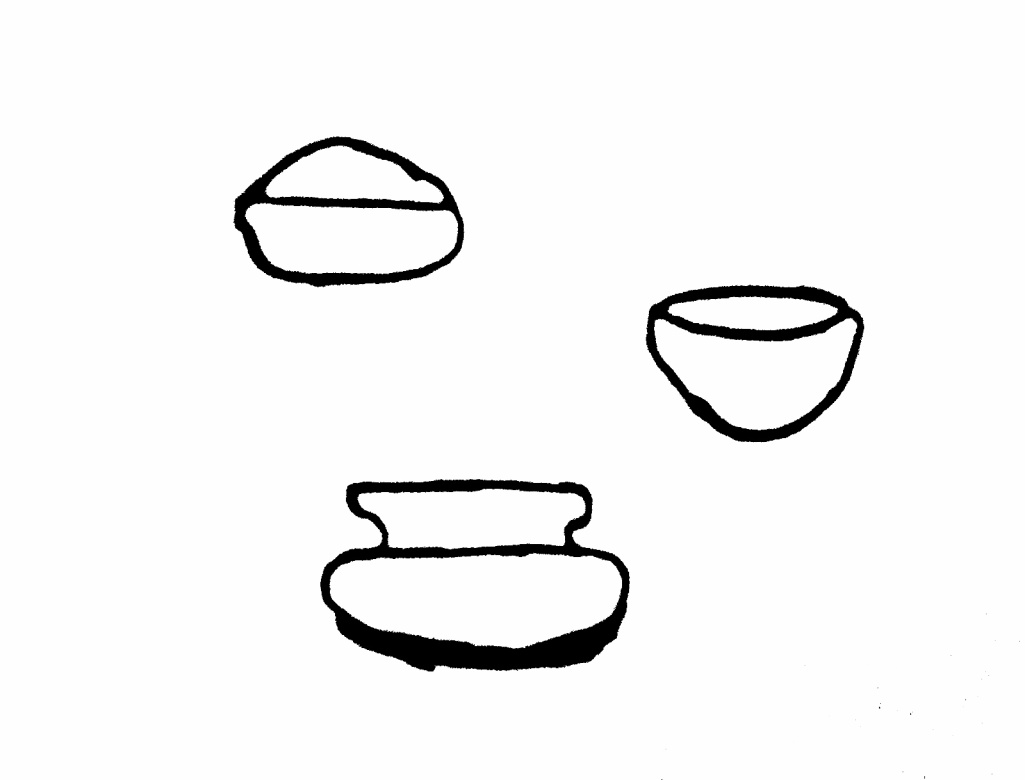

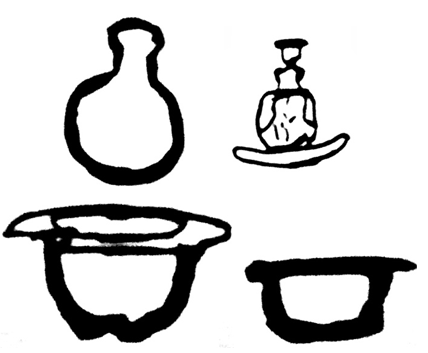

3. Bowles, Cups, Bottles

- Sufis and dervishes used a wide range of potteries in eating and drinking such as wine bottles, in addition to some wooden spoons with varied decorations. We have found many plates featuring Sufi and dervish drinkers using both pottery and porcelain ware. The plates also featured the wine makers.These potteries, glass and porcelain wares featured a wide range of plant and geometric trappings with wonderful colors. The six-fold geometric trappings were the most common type. They were similar to hives with blue, black, yellow and brown colours. They were also varied in size and the material they were made of. (see plates 4,5,6,7,10,14. fig.3,5,7).Findings● Islamic Sufism has influenced the Indian arts, notably painting, during the Mongolian era .The artists depicted every aspect of Sufis' life including their religious life, outgoings, and meetings with Mongolian rulers and emperors.● The Mongolian paintings for Sufis and dervishes in India paid a careful attention to all related belongings and details.Sufis and dervishes' belongings are divided into two main groups:1) Belongings for religious rituals: instruments used in singing and dancing during Sufis' circles of remember anceor outgoings; these tools include tambour, flute, pipe, trumpet, tabor, parchment and drum. This group also contains the prayer beads, books, and the staff. 2) Belongings used in food, drink and smoking. They were varied in shape and the raw material which they were made of throughout the Mongolian age. These belongings include: Kashkul, Narghile, receptacles, cups and bottles. ● Sufis and dervishes' belongings have their own symbolisms● These belongings possessed a wide range of plant, geometric and written trappings.● Iranian influences appeared clearly in most of Sufis and dervishes' belongings through painting and their trappings. This is an expected result due to a number of reasons through which these influences passed through. Above all were the Iranian artists in India and Mongolia.

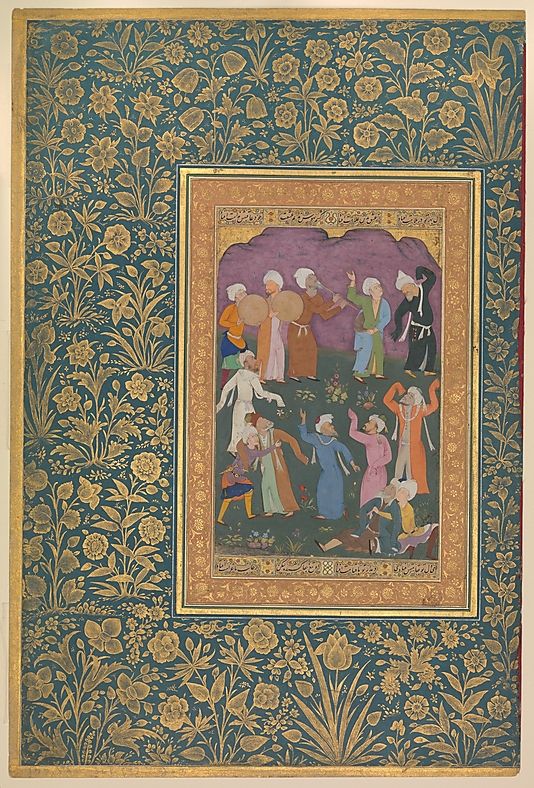

| Plate (1). Shah Akbar speaks With Dervish. Produce Abdul Samad Kalam, 1586 - 1587 AD, reserved in the Aga Khan Museum |

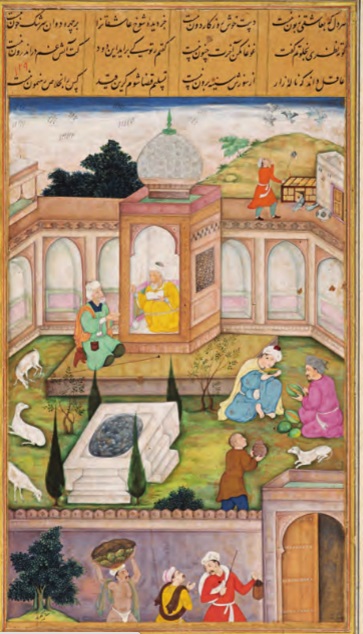

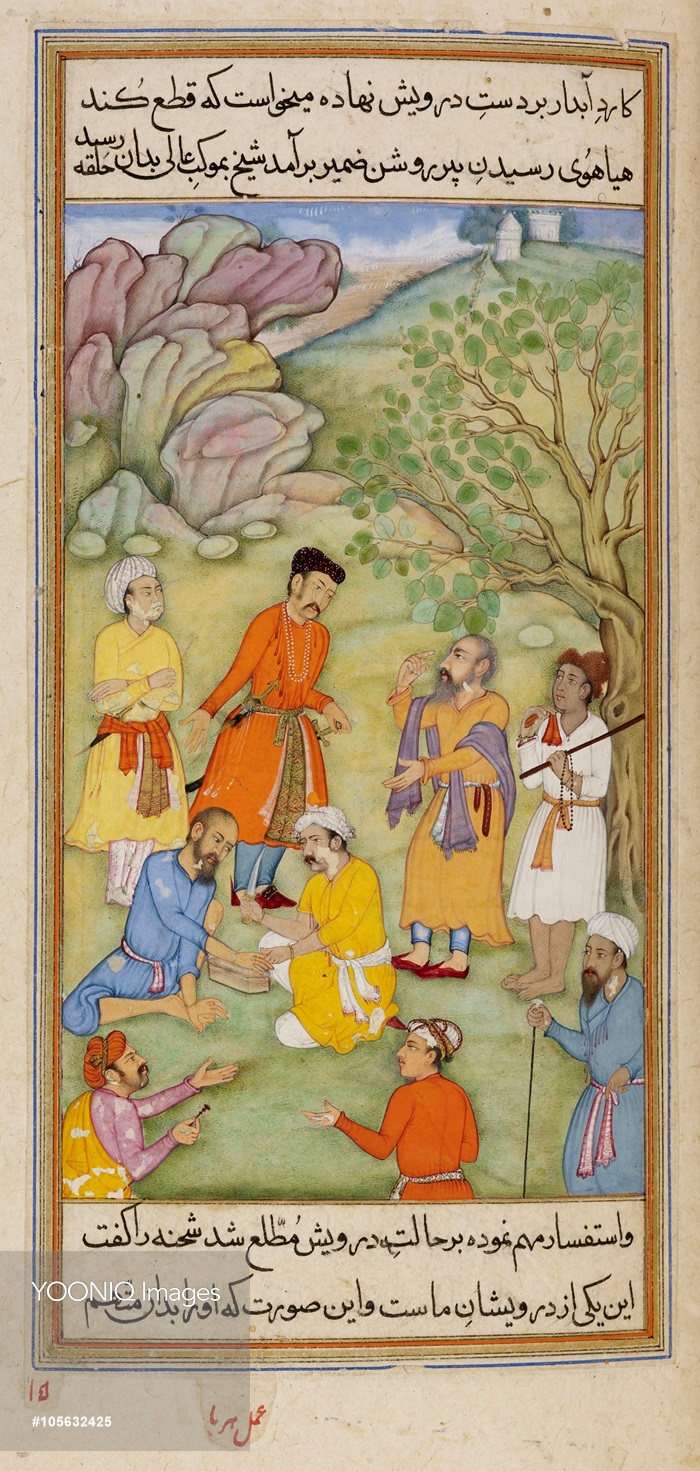

| Plate (2). Dervish peaks to his disciple one of the schools, the manuscript Saadi, India.1604 AD, reserved in Agha Museum |

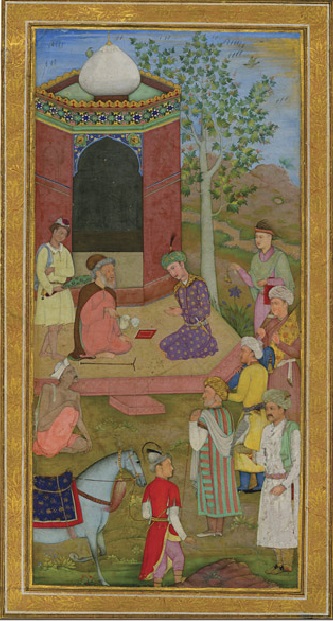

| Plate (3). Emperor meets the Dervish in Soumath, India.1610 AD, reserved British Museum in London |

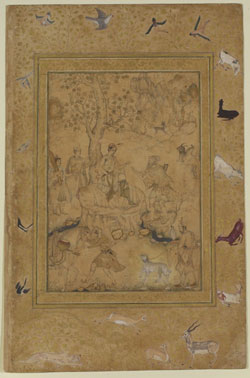

| Plate (4). A group of dervishes in the open, India,11 AH / 17 AD, reserved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York |

| Plate (5). A group of dervishes in the open during smoking and drinking, India, 1600 AD, reserved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York |

| Plate (6). A group of dervishes in the open, India 1605, offered Metropolitan Museum in New York from 1927 - 1929 AD |

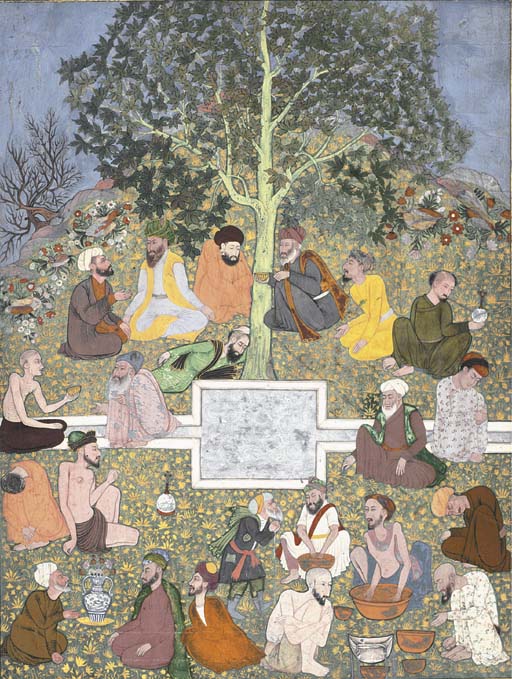

| Plate (7). A group of dervishes In hearing the ring and mention Square tomb of Sheikh Moinu ELDin Chty in Ajmer, 1650-1655 AD, preserved at the Museum of Victoria and Albert |

| Plate (8). A group of dervishes in the open, India dating from 1610 - 1611 AD |

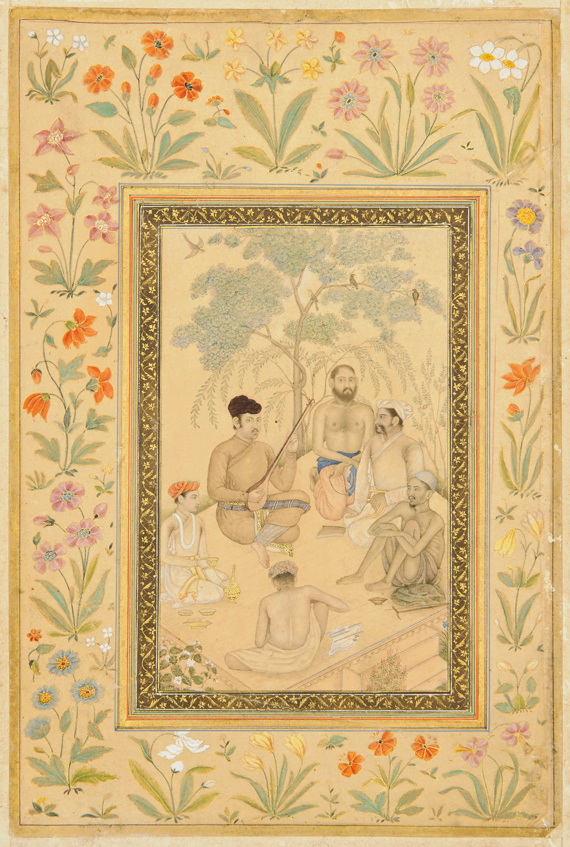

| Plate (9). A group of dervishes in listening to music in the open session, India about 1800AD |

| Plate (10). A group of dervishes in the hearing and mention, from India, 11AH /17AD, reserved the Pergamon Museum |

| Plate (11). Darwish speaks to the Emperor Akbar, from India in 1595AD, reserved Bodleian Library in Oxford |

| Plate (12). A group of dervishes in the ring and hear mention, of India 1770AD, reserved the library Alboudlah in Oxford |

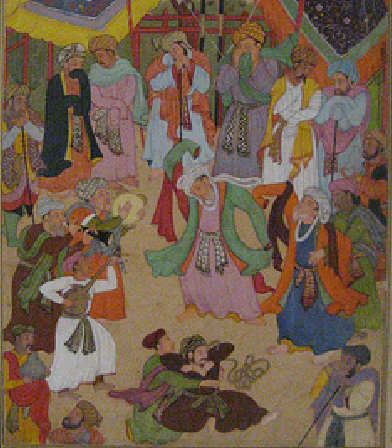

| Plate (13). Dervish dance in mention ring,Shah Jahan Album, India, 11AH /17 AD, reserved the Metropolitan Museum in New York |

| Plate (14). A group of Dervishes in the ring and mention hearing, India 1600AD, reserved the Metropolitan Museum in New York |

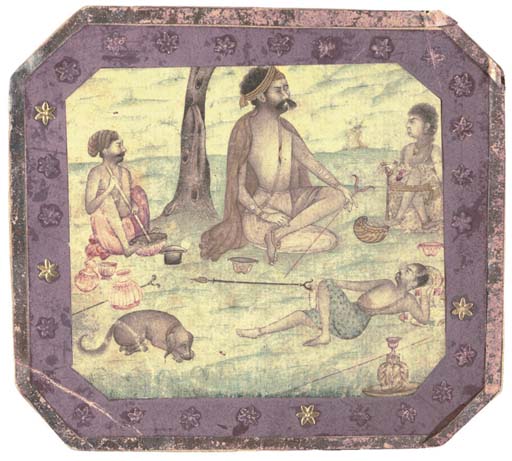

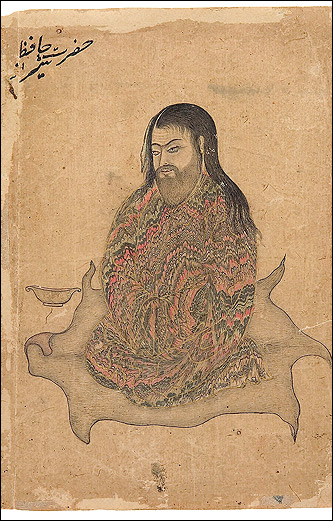

| Plate (15). Darwish Sitting in the case of meditation, India, 1650AD, preserved at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston |

| Figure 1. Stick "Crutch" from the plate (3). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 2. Book from the plate (3). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 3. Pots food and drink from the plate (4)."the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 4. Stick "Crutch" from the plate (5). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 5. Pots food and drink from the plate (5). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 6. Narghile from the plate (6). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 7. Pots food and drink from the plate (6). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 8. Tanbora from the plate (7). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 9. Trumpet "horn from the plate (11) ."the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 10. Drum for plate (12). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 11. Ney from the plate (13). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 12. Tanbora from the plate (12). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 13. Tabor from the plate (14). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 14. Kashkul from the plate (15). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 15. Prayer beads from the plate (14). "the work of a researcher" |

| Figure 16. Tambourines from the plate (13). "the work of a researcher" |

Notes

- 1. Sufis played a great role during the Mongolian rule of India, and were highly welcomed by the Mongolian rulers, for further about Sufis during this era see:- V.D. Mahajan: History of Medieval India "Sultanate Period And Mughal Period", S. Chand & Company 2011, PP, 367: 383.2. Imam Zahid Hnad ibn ALSeryi ALKoffi: ALZohad, Review: Mohammed Abu Laith ALKhair, the first part, presses the modern state of Qatar, p. 45.3. Mohammed Zaki Mubarak: the impact of Islamic mysticism in literature and ethics, manuscript Ph.D, Faculty of Arts - Cairo University, 1936, p. 271.4. Pope (A.U) : A survey of Persian art from prehistoric times to the present , oxford university press , London and New York 1939, vol, III, p, 2807 5. Iranian influences covered many areas, notably the depiction. These influences have channeled to India through Iranian artists mainly. Further on Iranian influences on Indian arts see:- Ananda K. Coomara Swamy, An introduction to Indian art, translated by Dr Amir Hossein- Zekrgoo, Tehran, Rozaneh Publication, 2003, pp. 183-189 - Hamada Mahmoud Thabet: Iranian Effects On the arts of Mughal Indian artifacts in the light of Applied through 12:10 AH (18:16 AD) , manuscripts PhD Thesis, University of Tanta, 2014, p. 47: 936. C V Raman: On some Indian stringed instruments, Calcutt, 1921, pp, 468: 472. More about tambora see:- M. Van Walstijn and V. Chatziioannou: Numerical Simulation of Tanpura String Vibrations, Le Mans, France 2014, p, 610: 614.- Paritosh K. Pandya: Beyond Swayambhu Gandhar, An Analysis of Perceived Tanpura Notes, Mumbai, p, 1: 10.7. ALSayied Ade Cher: Arabized Persian words, second edition, Beirut 1987 - 1988, p. 156.8. Lexicon the brief: especially the Ministry of Education edition, Egypt. 1999 p. 598.9. Salah Ahmed Bahnasy: singing views In Painting Iranian in The Timure and Safavid eras, Madbouly Library, Cairo, 1989, p. 207.10. Maher Said Hilal: ALTekke ALMoulouya - the study of archaeological civilized, manuscript Master Thesis, Faculty of Archaeology - Cairo University, 2003, p.92. 11. Maher Said Hilal: ALTekke ALMoulouya, p.91.12. Salah Ahmed Bahnasy: singing views In Painting Iranian, P.209.13. Sernai is a Persian word means pipe, it literally means the black pipe.- Salah Ahmed Bahnasy: singing views In Painting Iranian, P.209.14. Fatima Fouad: Listening at Sufi Islam, the Egyptian General Book Authority, 1997, p. 82.15. Lexicon the brief.p.67.16. Salah Ahmed Bahnasy: singing views, p.211.- Pope (A.U): Survey of Persian art, vol, VI, p, 2797.17. Salah Ahmed Bahnasy: singing views, p.211.18. Fathi Alsnfawy: the history of Egyptian folk musical instruments, the Egyptian General Authority for the book, 2000, p. 18.19. Lexicon the brief.p.230.20. Fathi Alsnfawy: the history of Egyptian folk, p.64.21. Maher Said Hilal: ALTekke ALMoulouya, p.94.22. Maher Said Hilal: ALTekke ALMoulouya, p.94.23. Fathi Alsnfawy: the history of Egyptian folk, p.70.24. Mohammed Imran: Dictionary of Popular Music Egyptian terms, Ain to the Humanities and Social Studies and Research, the first 2002 edition, p. 240.25. Lexicon the brief.p.356.26. Fathi Alsnfawy: the history of Egyptian folk, p.14.27. Fathi Alsnfawy: the history of Egyptian folk, p.14.28. Adze is a doubled-face drum being knocked on it by a leather belt or a wooden stick. There is a type of it with one sheepskin surface.- Matine Anad: Turkish dance, translator has the status of Languages and Translation - Academy of Arts, a review of Dr. Majda Ezz, the Supreme Council of Antiquities Press, 1976, p. 65.29. Salah Ahmed Bahnasy: singing views, p.211.30. Maher Said Hilal: ALTekke ALMoulouya, p.96.31. Lexicon the brief. p.300.32. Abd ELNaeem Mohammed Hassanein: Persian Dictionary (Persia / Arabic), Dar Egyptian Book - Cairo, Dar Lebanese Book - Beirut, first edition 1982, p. 348.33. Abdul Razzaq ALKashani:Lataief ALAilam Fie Isharat Ahal ALAilham "Glossary of terms and symbols of Sufism", the first part, review and study, Saeed Abdel Fattah, first edition 1996, p. 468 .34. Qur'an, Surat ALAnkabout. Aya45.35. Mohiuddin Tamy: the revival of the Sufi Science, Volume II, cultural Library - Beirut, first edition, 1994, p. 29.36. Mamdouh Alzuby: Sufi lexicon, Dar-generation publishing, printing and distribution, first edition 2004, p. 204.37. Asim Mohammed Rizk: Khanquaoat Sufism in Egypt in the Ayyubid and Mamluk (567-923 AH / 1171-1517 AD), the first part, Madbouly Library, Cairo, 1997, p. 52.38. Bader Abdul Aziz: Burda texts on the Ottoman monuments in Egypt, Thesis, Faculty of Archaeology - Cairo University, 2002, p.50.39. Robinson (F): Atlas de l'islam, depuis 1500, Nathan, paris 1987, p, 40.40. Ramy Mohsen Younis: the images of Sufis, Zhad, hermits and dervishes in Iran since the beginning of the Mughal era and until the end of the era Safavid period artwork comparative study in the period of "656 AH / 1258" to "1148 AH / 1736 AD", manuscript Master Thesis, Faculty of Arts - University Helwan, 2010, p. 270.41. Ramy Mohsen Younis: the images of Sufis, p.217.42. Mathnawi, twice, means that every poetry two lines have to end with the same vowels.-Abd ELNaeem Mohammed Hassanein: Persian Dictionary. p.626.The book is considered the greatest poetry epos in the history of Islamic Sufism, written by Jala Addin Al-rumi and has been considered a reference to the Moloyia order.-Abd ELNaeem Mohammed Hassanein: Persian Dictionary. p.626. 43. The logic of birds, an epos written by Farid Addin Al-attar, a great sufi poet. The title refers to a journey of birds, leading by the hoopoe, and their struggle to pass the seven valleys in order to reach al-semragh at Qaf mountain that enclave whole the world. The epos mentioned also their passing away following getting the eternal life. Al-Attar aimed to illustrate the degrees of people of thankfulness according to the Sufism perspective and their suffering to reach the perfection. These degrees are summed up as following: demand, love, and the knowledge, this road is too hard to be cross through except for one out of hundreds of thousands, following that the degree of renunciation, passionate, uncertainty, then the highest degree which is the passing away or mortality.-Tharwat Okasha: art history, photography Persian and Turkish, Arab Foundation for Studies and Publishing, the first edition, 1983, p. 323. 44. Abu-Hamad Mahmoud Farghali: influence of religious trends in the work of Reta Abbasi, a seminar Islamic monuments in the east of the Muslim world, the Faculty of Archaeology - University of Cairo, November 30-December 1, 1998, p. 605.45. Lexicon the brief.p.422.46. Abdel-Moneim El-Hefny: Lexicon mystical terms, Dar march - Beirut, second edition 1987, p. 184.47. Abu-Hamad Mahmoud Farghali: influence of religious trends, p.608.48. Qur'an, Surat ALAaraf. Aya117-121.49. Abu-Hamad Mahmoud Farghali: influence of religious trends, p.608.50. Qur'an, Surat ALShoaraa. Aya 63-66.51. Ramy Mohsen Younis: the images of Sufis, p.268.52. Ade Cher: Arabized Persian words, p. 135.53. Seham Abdulla Gad: Mineral Safavid artifacts in the light of Applied artifacts and photographs manuscripts, Master Thesis, Faculty of Archaeology - University of Cairo, 2004, Vol. I, p. 51- Sabiha Al Khemir: Beauty and Belief, Crossing Bridges with the Arts of Islamic Culture, 2013, p.15.54. Mohammed Altonjy: ALZahbiy lexicon (Persia / Arabic), House science to millions, Beirut, second edition 1980, p.469.55. Mervat Mahmoud Issa: ALkaskul Between the symbolic figure and symbolic motifs, Journal of Arab Archaeologists Association, third edition, January 2002, p. 124.56. Mervat Mahmoud Issa: ALkaskul, p.121.57. Ramy Mohsen Younis: the images of Sufis, p.262.58. Souad Maher: Islamic Arts, the Egyptian General Book Authority, 1986, p.14359. Pope (A.U): A survey of persian art, vol "3", p, 251560. Ramy Mohsen Younis: the images of Sufis, p.263.61. Mervat Mahmoud Issa: ALkaskul, p.126.62. Souad Maher: Mashhad of Imam Ali in Najaf and its gifts and antiques, house knowledge in Egypt in 1969, p. 354.Further on kashkol see:- Amin Abdullah Rashidi: study and publication of the kaskul of porcelain from the ulnar era in Iran preserved in a private collection in the United States of America, historical facts, 2013, p. 277: 329.63. Tobia Anesi: explanation Extraneous words in the Arabic language with the letters with male origin, Dar Arabs 1988- 1989, p. 72.- Ade Cher: Arabized Persian words, p.151.64. Lexicon the brief. p.607-609.65. Essam Adel Morsi: coffee houses and tools of Egypt in 10AH/16AD century until the end of 13 AH/19AD civilized archaeological study, Master Thesis, Faculty of Archaeology - Cairo University 1988, Vol. I, p. 264.66. Faiza Mahmoud Abdul Khaliq: Smoking tools in Egypt in the era of Muhammad Ali, civilized archaeological study in light of the group Gayer-Anderson Museum Manial Palace, Faculty of Archaeology magazine, No. VI, the University of Cairo Press writers university, 1995, p.426-427.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML